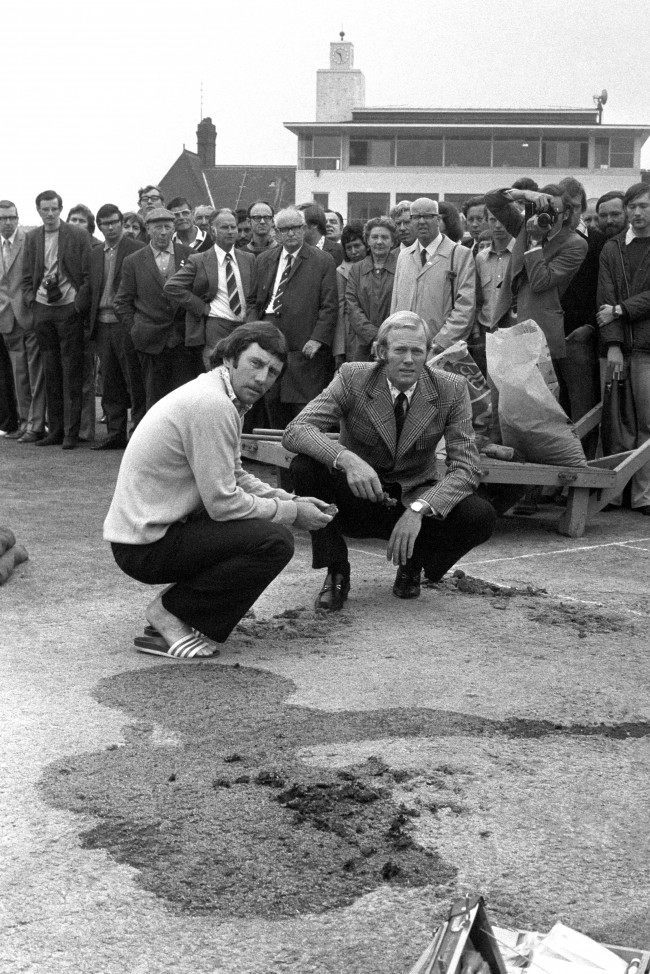

On August 19, 1975, the third England v Australia Test at Headingley was abandoned following vandalism. A man who said he was a supporter of the George Davis campaign telephoned BBC Radio London and claimed the group was responsible. Slogans were daubed outside the ground. The wicket was damaged with a spot of digging and poured oil.

The Test was declared a draw robbing England of the chance to win back The Ashes and the trophy.

In the picture below, Australian cricket team captain Ian Chappell and his England counterpart, Tony Greig, inspect the vandalised pitch.

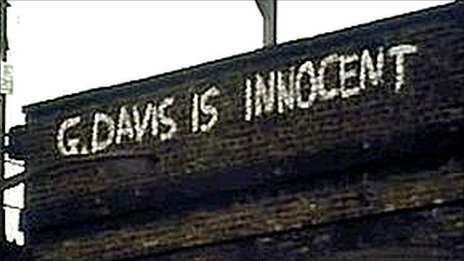

The words “George Davis is innocent” can still be seen on some motorway bridges.

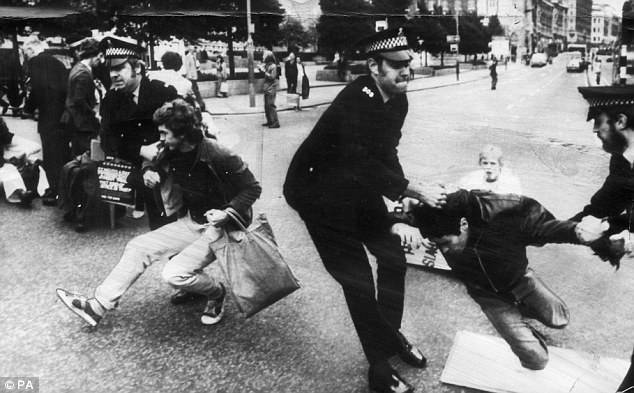

In this shot, the policeman with the large mutton chops seems to be guarding the heavy roller.

So who was Davis? Who wanted him free? And why wasn’t he free?

Davis was an east London minicab driver jailed for his part in an armed robbery. In 1975, he was sentenced to a 20-year prison term, beginning at Albany Prison on the Isle of Wight.

The robbery took place at the London Electricity Board’s offices in Ilford, Essex, on 4 April 1974. During the attack a police officer was shot and injured. A second officer was run over. Four men were arrested. Only Davis was convicted. He said he had been fitted up by the police. Davis never let up protesting his innocence. Rose Davis, his wife, believed him. So too did Davis’ best friend, Peter Chappell. He said he’d seen Davis driving his mini cab at the time of the robbery. It was Chappell who had dug up the cricket pitch in Leeds.

No-one in power believed any of them.

One witness claimed to have seen him abandoning the getaway car. Davis claimed he had been driving a mini- cab on the morning of the crime, delivering a consignment of fish to a restaurant in Chancery Lane. None of the blood samples found at the scene matched his blood type.

In May two campaigners – Davis’ brothers-in-law Jim and Colin Dean – carried out a seven-hour roof-top protest at St Paul’s Cathedral in London.

But Chappell was the driving force in the campaign to free George Davis, literally – he drove a van down Fleet Street, smashing through the front windows of the Daily Telegraph and Daily Mirror newspapers. He later drove through the gates of Buckingham Palace. As Adam Curtis notes, Chappell went to Paris on the ferry and drove through the windows of the British Embassy.

And then there was the 1974 Christmas incident in which Peter Chappell blew the lights on the Christmas tree in Trafalgar Square as Rose Davis stood vigil for her husband outside Scotland Yard.

The campaign grew. This was the working man against the powerful, paternalistic State.

The Who performed a benefit concert for Davis at Charlton Athletic’s The Valley football ground. Rose and the band all sported “George Davis Is Innocent” T-shirts. The radical Half Moon theatre company staged a play, George Davis Is Innocent OK, at its tiny theatre in Aldgate.

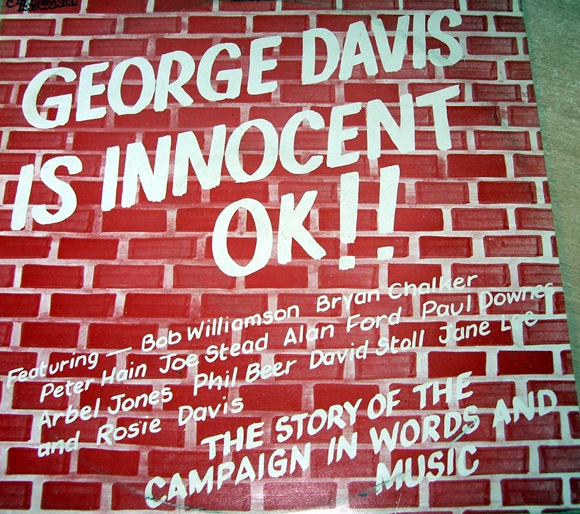

There was an album, featuring tracks by Bob Williamson, Bryan Chalker, Peter Hain, Joe Stead, Alan Ford, Paul Downs, Arbel Jones, Phil Beer, David Stoll, Jane Lee & Rosie Davis.

(Peter Hain would become a Labour MP and serve in the Cabinets of Tony Blair and Gordon Brown. In 1975, he was framed by the South African secret police for robbing a bank. He was acquitted after an Old Bailey trial.)

But the Headingley stunt was the one that really pricked the public conscience. Of the four people tried for digging up the pitch, three received suspended sentences. Peter Chappell was jailed for 18 months.

…punks, radical lawyers, revolutionaries, east-end squatters and artists, and lots and lots of ordinary people who were shocked by the miscarriage of justice. Rose Davis called these groups “soap avoiders”. She said – “they are very intellectual, but most of them never wash”.

And the graffiti kept Davis in the public eye, OK:

Observer writer Robert Chesshyre wondered what was going on:

“First I had to convince the Observer’s editor, David Astor. He had moulded the Observer as the intelligent liberal flagship of the postwar press, but his interests were, on the whole, affairs of state, national policy, topics of concern to the great and the good. Would he buy this tale of a hoodlum and his campaigning wife and friend? Astor had two main questions. Did I genuinely think Davis had been wrongfully convicted? And, if I did, was it of consequence, set against the lofty events with which the paper then mainly concerned itself?

“Sucking a mint, Astor pondered. It wasn’t his sort of story he said finally, but he could see that times were changing and that if a man had received 20 years for a crime he hadn’t committed, we shouldn’t sleep easy until he’d been freed.”

Chesshyre wrote up his findings:

“There was no forensic link between Davis and the robbery. The police relied on identification evidence and Davis’ supposed statement, which he claimed contained words made up and inserted by a police officer.

Davis was picked out at an ID parade by three policemen, all of whom had been travelling in the same car. At a second set of parades held three months after the crime, 34 out of 39 witnesses failed to pick out Davis. And three made wrong identifications.

Two ‘mistakes’ were made after Davis swapped his shirt with another man, who was then identified – an odd event at the very least.”

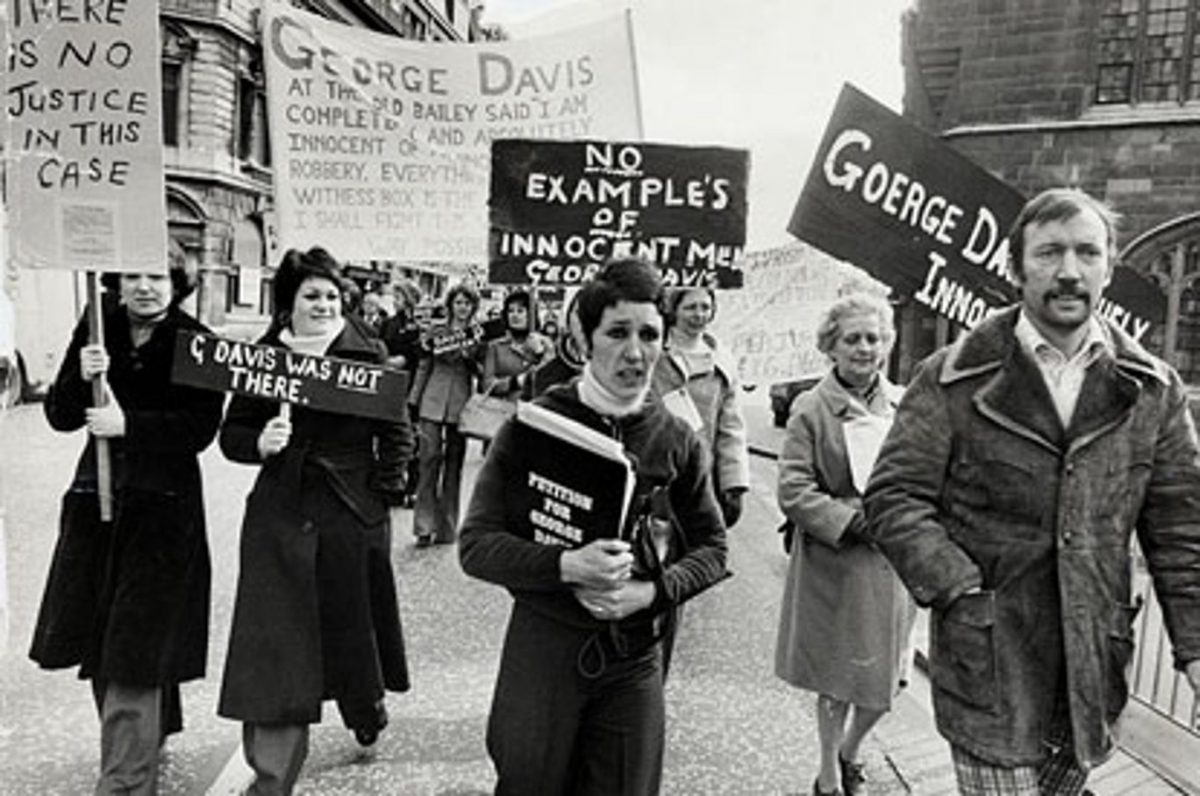

Friends And Family Of Convicted Armed Robber George Davis Including His Wife Rosie Davis Protest His Innocence By Marching From Tower Hill To Downing Street To Hand In A Protest Letter To The Prime Minister – 5 Apr 1975

Did the police send innocent people to prison?

Yes.

Did the police lie on oath?

Yes.

Was there corruption in Scotland Yard’s Robbery Squad?

Yes.

The head of the Robbery Squad in those days was none other than the legendary Jack Slipper, ‘Slipper of the Yard’, the man who rounded up the Great Train Robbers.

An outside police police investigated the Robbery Squad. They reported back to the Home Office. Home Secretary Roy Jenkins announced that Davis must be released. On May 1976, he was. But the Home Office ruled that the reasons behind his incarceration would remain secret for 34 years.

Roy Jenkins said there was serious doubt about his identification.

Davis’s sentence was remitted by Royal Prerogative, a series of historic powers officially derived from the Crown from medieval times that have, in reality, been passed to politicians. They enable decisions to be taken without the backing of, or consultation with, Parliament.

Power was being tested. In 2011, Davis’ lawyer Bernard Carnell had this to say:

“One of the pieces of the jigsaw was the evidence of the woman whose car was hijacked by the robber with her and her children still in the car. After the trial she saw pictures of George Davis in the Daily Mirror and told the police investigation that because of the pictures she was satisfied the person in the car was not George Davis. That evidence has been in possession of the authorities for 35 years and was made available to me only last year.”

Davis was a legend. He let the fame go to his head.

Here are two photos of Davis’s arrival at London’s Waterloo Station following his release from prison. Rose is planting a kiss on his cheek.

Davis was an idol of the punk movement. Sham 69’s 1978 debut album Tell Us the Truth, was tribute to him:

Only, he was arrested again in 1977 and later admitted his part in an armed robbery at the Bank of Cyprus on Holloway Road, London. He was sentenced to 15 years which was reduced to 11 years on appeal.

He’d also been cheating on Rose. Mrs Davis felt let down, noting in her autobiography, The Wars Of Rosie:

“Once he’d done what he’d done, I was ashamed… I was never a gangster’s wife. And so I stopped defending him. I felt guilty, like a traitor really… I felt gutted for all those people who had helped us.”

Once again she made her way to a police station to make a stand, telling the desk sergeant:

“Would you give my husband these clothes and tell him I forgot the rope.” “Rope?” “Yes, to hang his ——- self with.”

They divorced.

Davis was freed in 1984 but three years later he was sentenced to 18-months for attempting to steal mailbags. After his release, he marred for a second time. His bride was a London Chief Inspector’s daughter.

George Davis Is Pictured With His First Wife Rose (died 31/01/2009) In The Back Of A Car After Being Released From Prison Early. 12 May 1976

Davis was a villain. But the never did rob the Ilford Electricity Board. In 2009, the Daily Mail’s Andrew Malone still hadn’t understood what the man’s story represented:

Despite what his gullible Left-wing supporters thought at the time, his original conviction may have been correct and it has never been officially overturned. His other convictions are beyond question.

It wasn’t just about Davis. It was about police lies sending a man to prison. It was about authority being questioned and found wanting. It was the story of a slogan that went ‘viral’ and a campaign that achieved its aims. It was about lies being maintained by secrecy backed by arcane laws.

In May 2011, George Davis finally won his appeal against that 1975 conviction. Three Court of Appeal judges declared his conviction “unsafe”. But they said they could not “positively exonerate him”.

Lord Justice Hughes said:

“We do not know whether Davis was guilty or not, but his conviction cannot be said to be safe. As we have made clear, the fact that he was an active and known criminal does not affect this question, nor does it make it any the less important that his conviction should not be upheld unless it is clear that it is safe.”

Said Davis, then age 69:

“This is a bittersweet moment for me. I am, of course, delighted that my conviction has been quashed. I have been protesting my innocence since 1974, and always claimed I was falsely identified. But it should not have taken 36 long years to stand here like this.”

How can police lies and an unsafe conviction not mean that George Davis is innocent?

Has anything changed?

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.