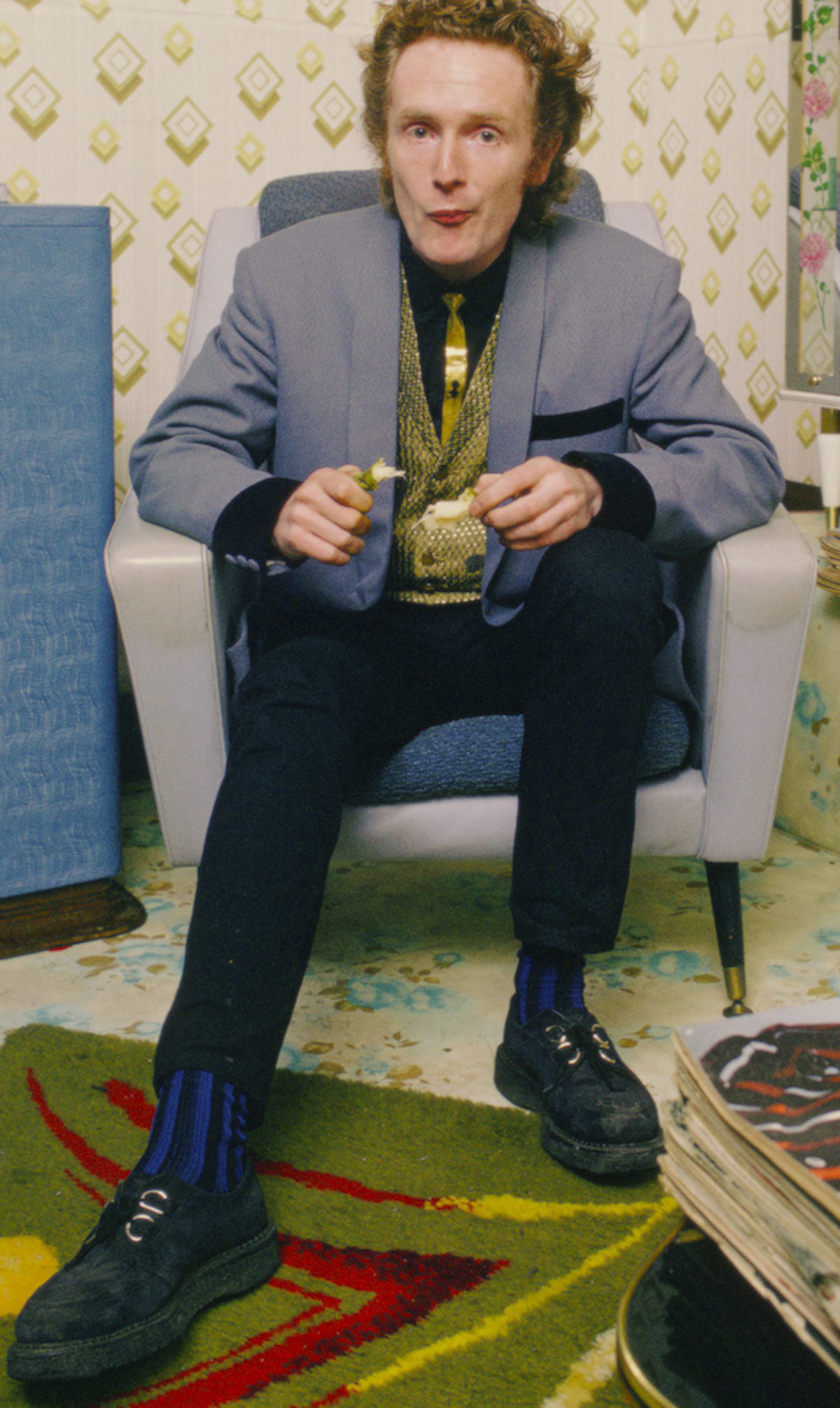

When the late Malcolm McLaren purchased a pair of suede D-ring creepers from the pop-art boutique Mr Freedom at the height of hippie-dom in 1970, the Sex Pistols manager and partner of Vivienne Westwood acknowledged what is today accepted as an undisputed truth: George Cox combines originality and authenticity with design excellence, independent creativity and great British craftsmanship.

Malcolm McLaren in a previously unpublished shot wearing original 50s George Cox Bingley D-ring brothel creepers to match his detail-perfect Teddy Boy garb. Photo taken inside Let It Rock, 430 King’s Road, January 1972. (c) David Parkinson

With deep pop culture roots, George Cox footwear has been an indispensable element in the look of subcultures for decades, from Teds and Rockers to Punks, Rockabillies and Retro-Futurists; after all, the company revolutionized the visual identity of youth by introducing the world’s first creeper nearly 70 years ago.

This was but one of the factors which convinced the visually-savvy McLaren and Westwood as to the brand’s credibility; that’s why they turned up unannounced at the George Cox factory a few years after he bought that first pair of creepers and ordered six different styles to sell in their Chelsea emporium Let It Rock (not-so-coincidentally at the very same premises which had hosted Mr Freedom).

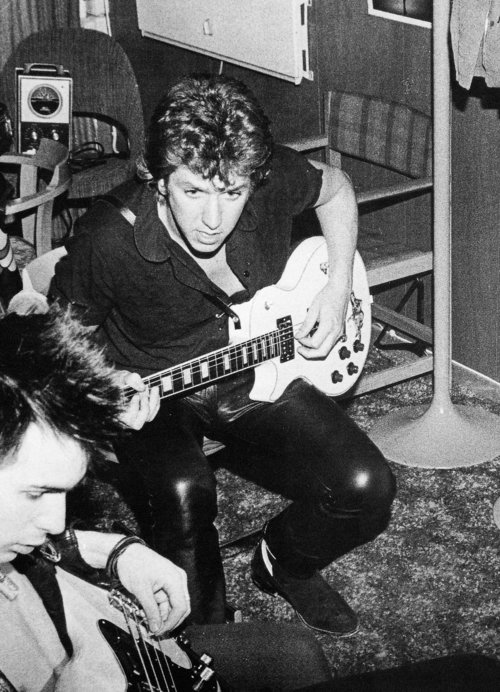

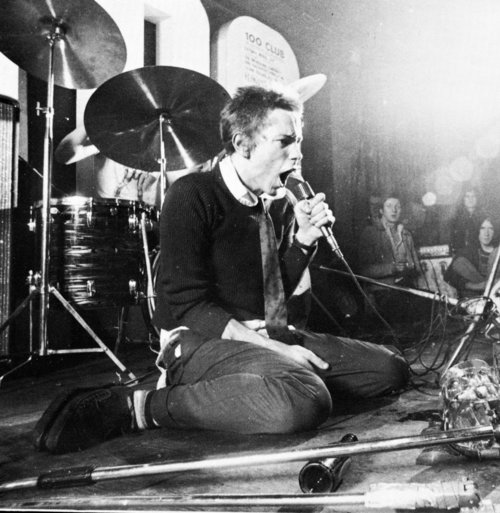

Subsequently McLaren and Westwood transformed Let It Rock into SEX and then Seditionaries, making 430 King’s Road the seedbed for the incendiary Punk movement whose provocations reverberate to this day; through this period George Cox was the main shoe supplier, and the company’s creepers and other designs including winklepickers and Jodphur Boots became the footwear of choice for such legends as Johnny Rotten, Paul Simonon, Joe Strummer, The Slits and Sid Vicious.

Today, George Cox shoes are the benchmark for 21st Century style rebels on the street and on the catwalk, from achingly hip labels such as Bathing Ape, Yohji Yamamoto and Human Made to a host of super-stylists and fashion editors including Paris Vogue’s Emmanuelle Alt.

Part of the allure is down to George Cox shoes having transcended fashion; they are not only design statements but also lifestyle choices. For these reasons the likes of Robbie Williams, Johnny Depp, Ewan McGregor, Adam Ant, Alice Cooper, Korean star Kris Wu and Jack Nicholson amp up their cool by choosing George Cox.

Last year marked an exciting new phase for the fifth-generation family business. The launch of a new website with an e-commerce wing and a literal reboot with a refreshed core selection coincides with a collaboration with Comme des Garçons. The label’s principal Rei Kawakubo – in 2017 the subject of the critically lauded major retrospective at New York’s Metropolitan Museum Of Art – has long been a George Cox fan and understands that the brand is a perfect fit with Comme des Garçons .

With the post-digital return of interest among stylish consumers in analogue design, authenticity, craft and independent values, it’s worth considering just how far George Cox has come since it was established in 1906 as a side-line by brewery worker George James Cox.

At the start his range comprised just two styles: traditional Derby and Oxford shoes available in black or brown, but after the end of the First World War business was sufficient for Cox to convert a former swimming pool in Wellingborough into a shoe factory, which he named Castle Works.

His son George Hamilton Cox, known as “Ham”, was sent to college to learn the shoemaking trade and was soon lugging sample cases around the Midlands building up the name and reputation of the business, which was incorporated in 1934.

Under Ham the company started selling around the country and expanded into retail with the Chris Hatton chain of shops. It was during the post-war period that George Cox moved into fashion with new styles aimed at freshly demobbed young adults and those customers who would soon be dubbed “teenagers”.

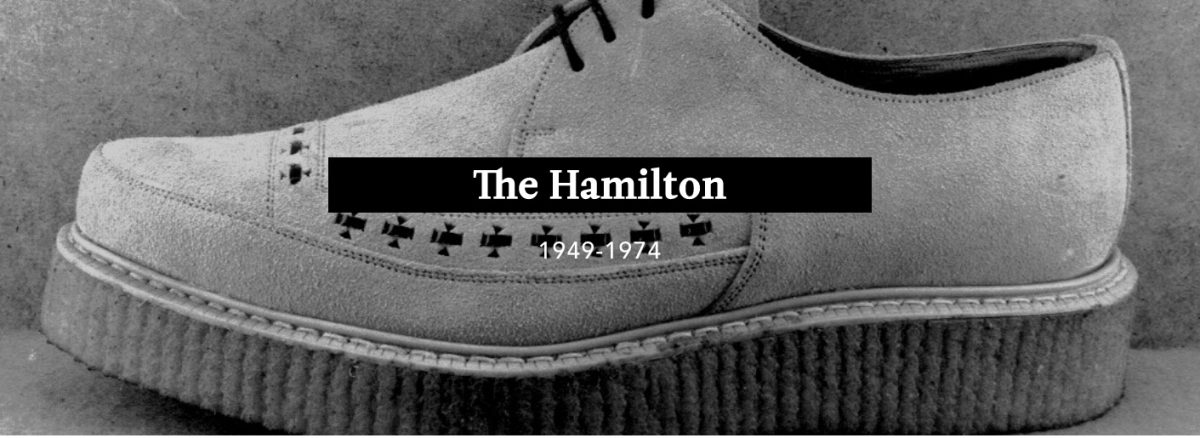

In 1949 Cox’s London agent, a Mr Lew Fish, identified a new type of shoe design which was becoming popular and is thought to have originated in Paris: this featured thick soles made from natural “plantation crepe”. Young mainly working class men were sporting these with the dandy neo-Edwardian clothing – drape suits, fancy waistcoats, Slim Jim ties – which had caught on as High Street tailors mimicked a trend which had started but faltered after one season in Savile Row.

Ham responded quickly and introduced a namesake style, The Hamilton; dubbed “brothel creepers” these became the chosen footwear of Britain’s first mass youth cult, the Teddy Boys.

In the 50s, with Ham’s son-in-law Norrie Waterfield on board, George Cox steadily built on its reputation for producing fashion shoes rather than the more traditional men’s styles peddled by competitors. Production flexibility was the key; at various times the factory even had substantial contracts for skating boots and sheepskin-lined bootees for Scandinavia!

As Teds gave way to Rockers, Modernists and then Mods and Beatniks in the 1960s, so George Cox was at the forefront of Continental-inspired fashion by developing Winklepickers and Beatle boots.

With his brothers, Adam Waterfield was one of the outworkers providing decorative handiwork and working at the George Cox factory during holidays in his teens; there was even a chunky-soled range in the 1970s named after them: Andrew, a men’s brogue, Tim, a men’s loafer, Adam, a “boy’s” brogue selling to girls, and James, a “boy’s” loafer.

These – in particular the Adam, as Waterfield recalls – became big on the country’s nascent club and disco scene, particularly among those frequenting Wigan’s hallowed Casino.

Such was the popularity of George Cox’s shoes in this period it took orders for 27,000 pairs of shoes at a single trade fair, at a time when it was producing at most 500 pairs a day.

It is largely forgotten now but 1968, which is logged in the annals of youth culture as a year of protest and tumult in London, Paris and across American cities, was also marked in the UK by a brief 1950s revival, largely as a reaction against the lank long hair and drab colours of hippie. The following year the entrepreneurs Trevor Myles and Tommy Roberts surfed this zeitgeist by opening their pop-art boutique Mr Freedom. Among the items they sold were original style brothel creepers in such vivid colours as blue and red. These were ordered from George Cox, and, of course, a pair – featuring D-rings and quilted tops – was bought by Malcolm McLaren.

By the time he and Vivienne Westwood visited Norrie Waterfield and ordered several different styles in 1973, their shop Let It Rock had been at the forefront of the 50s revival before switching to an obsession with rockers as Too Fast To Live Too Young To Die and then, as we have seen, becoming the incubator for Punk as the place where the Sex Pistols formed when it became SEX.

Pistols bassist Glen Matlock was the Saturday boy at 430 King’s Road and clearly recalls the popularity of George Cox shoes.

“We did unbelievably good business,” Matlock wrote in his memoir I Was A Teenage Sex Pistol. “Friday night or Saturday morning a lorry would turn up with a delivery of creepers – the very things which had enticed me into the shop in the first place. We’d stock up the shelves and by the middle of the afternoon all that would be left would be size 14s in puce and some size 5s that maybe a girl would pop in and buy for a party just before we shut.”

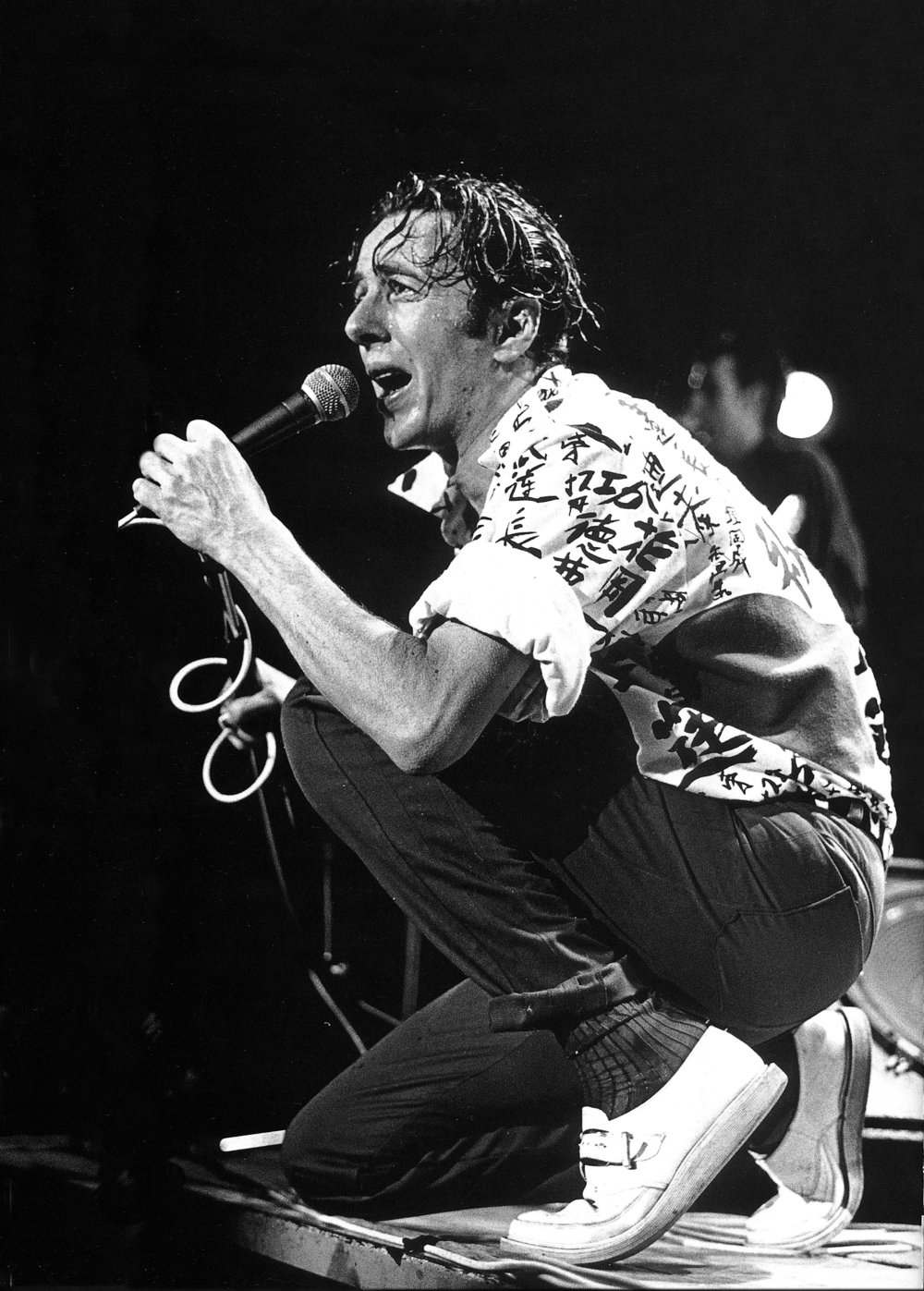

In fact Johnny Rotten – then John Lydon – obtained his audition for the Pistols when he visited the shop during its SEX phase on the hunt for a pair of George Cox shoes, according to McLaren.

“In came a very, very obstreperous creature looking for a pair of brothel creepers in white suede,” said McLaren. “I didn’t have them in his size but I could order them for him the week after.

“I asked him, as I was asking everyone who came in the shop at that time, ‘Do you sing?’ and he said ‘Nah—only out of tune.’

“I thought, ‘All right, we’ll test you.’ I told him, ‘If you want these shoes, I may even give them to you if you promise to head down to this pub round the corner where you can meet the rest of the band tonight’.”

And the rest is history…

In this way George Cox creepers, boots and shoes became a key element of the Punk Rock look, and, when Punk evolved into New Wave and Post Punk, the company tailored its styles into slightly less extreme Rockabilly-wear, worn by the likes of Elvis Costello, Squeeze and Madness.

This was propelled by a licence to produce Dr Martens; combining the company’s air-cushioned sole with pointed creeper upper in the early 1980s marked a significant design innovation and departure from the utilitarian products previously associated with that marque. The company continues to make these available, made in the same way, with its own sole.

The Robot retail outlets in Covent Garden and the Kings Road became a particular magnet for British and international style fans, and this was soon mirrored around the country.

“Every decent-sized city in the UK had a small shop in a scruffy location, run by young entrepreneurs, selling as many of our shoes as they could get hold of, in every colour under the sun,” says Adam Waterfield. “We had gone from a factory offering two styles in two colours to one where, when you looked at the possible choices of last, pattern, material, detailing, sole and welt, the variations ran into the hundreds of thousands.”

Not just the UK, but throughout the world, where pioneers such as Blue Moon in Germany, John Fluevog in Canada, Let it Rock in the USA, Figgins in Australia, Booster in Switzerland and American Import Export in Italy were introducing British subculture to their respective markets.

As the years progressed such remarkable boutiques as Boy, Johnsons, Red Or Dead and Shelly’s relied on George Cox to produce a dizzying array of footwear for thousands of customers, including notables from The Stray Cats to Billy Idol via Siouxsie Sioux and Bananarama.

In fact, in the 1980s, the George Cox factory was on permanent overtime, including Saturday mornings, employing around 120 people and producing at least 100,000 pairs a year for customers all over the world.

By the late 90s under Adam Waterfield, George Cox had become one of the biggest imported footwear brands in Japan, and at the turn of the Millennium the company won a succession of industry export awards, including one presented by Princess Anne, as well as a Queens Award For Enterprise.

Unlike many other established independent brands, George Cox has survived such challenges as the late Noughties recession, with popularity boosted particularly among women by such high-profile customers and photo-shoot models as Agyness Deyn, Rihanna, Jessie J, Nicki Minaj and Emma Watson.

And rocking titans such as Jack White understand the associations bestowed upon them by wearing George Cox shoes. A fan of the latter recalls an encounter with the White Stripes mainman thus: “When I saw he was wearing George Cox creepers I thought: ‘This guy knows far more than he’s letting on’.”

George Cox has retained a proud independence by plugging into its deep roots in the craft of shoe-making. “We have maintained a complete archive of our patterns, lasts and leather, and control our own cutting, putting the closing (sewing) and making out to various local factories,” emphasizes Adam Waterfield.

And the collaborations with leading fashion players the world over testifies to the brand’s enduring relevance.

With the involvement in all creative aspects of the company of Adam’s son Alistair Waterfield – a student a London’s vaunted Central Saint Martins who has also established himself as a leading fashion model – George Cox is gearing up for the future by continuing to produce designs which remain first in their field as emblems of style and subversion.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.