It was definitely a Saturday in September 1918, but no one could quite remember whether the party began on the evening of the 7th or a week later on the 14th. Odd, perhaps, considering that a few weeks later the night in question was described in court and in the press as ‘squalid’, ‘deplorable’ and even a ‘disgrace to modern civilisation’ – quite a charge considering the evening took place during the final weeks of the First World War. There was a reason, however, for the vagueness of the witnesses’ memories – they had all spent most of the night in an opium-based stupor.

Early on that warm September evening six people arrived at a flat on Dover Street, 100 yards or so north of Piccadilly, where a thirty-seven-year-old theatrical dress designer called Reggie de Veulle lived with his wife Pauline. Five years his senior, she too was a designer and they both worked at Hockley’s in Bond Street. At about nine o’clock a Scottish woman called Ada Ping You also came to the apartment, but she was shown into the drawing room while everyone else continued eating their supper. Ada, who with her Chinese husband Lo Ping You lived in a dilapidated house on the eastern end of Limehouse Causeway, sat in the middle of the room and began the initial preparations for the smoking of opium.

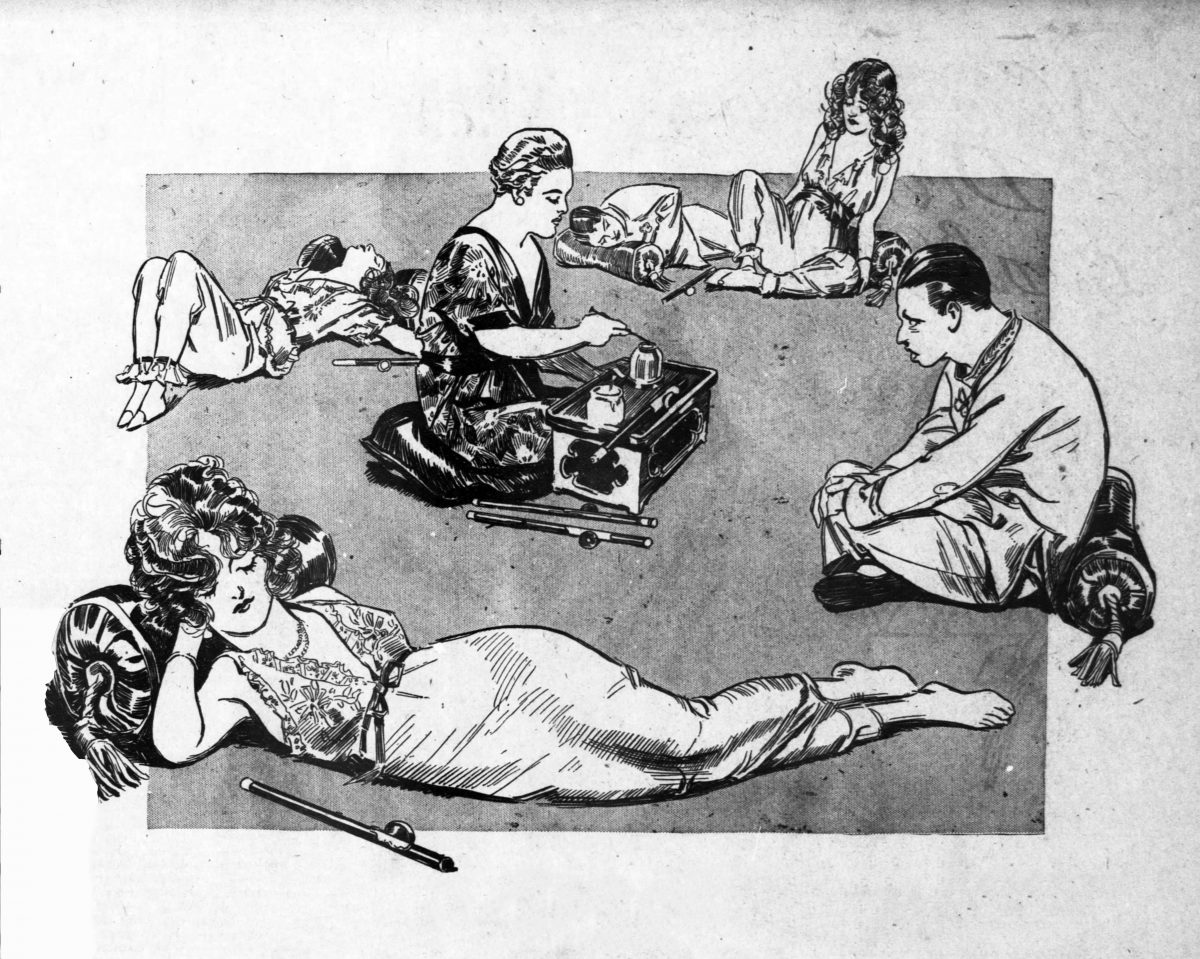

A contemporary illustration of the ‘sordid’ opium party at Dover Street in September 1918.

How the Dover Street flat of the de Veulles looks today.

An hour later, after they had divested themselves of their clothing, and with the men now dressed in pyjamas and the women in chiffon and crepe de chine nightdresses, the de Veulles and their guests reclined on the many cushions and pillows placed around the room. In a circle around Ping You they watched with excited anticipation as she took a pea-sized ball of the dark opium paste and, with the end of a long needle, held it over the faint blue flame of a peanut-oil lamp until it started to swell and turn golden. The gooey mass was stretched into long strings several times before it was rolled back into its pea shape and pushed into the hole of the bowl of the opium pipe. At about eleven, just as the pipe began to be passed around, another woman arrived at the flat. This time it was an actress, well known at the time, called Billie Carleton, who had been staying with the de Veulles and had come straight from the Haymarket Theatre where she had been performing in a light comedy called The Freedom of the Seas. After disrobing as well, she joined the rest of the circle. It was later reported that the party remained, apparently in a comatose state, until about three o’clock on the following afternoon, Sunday.

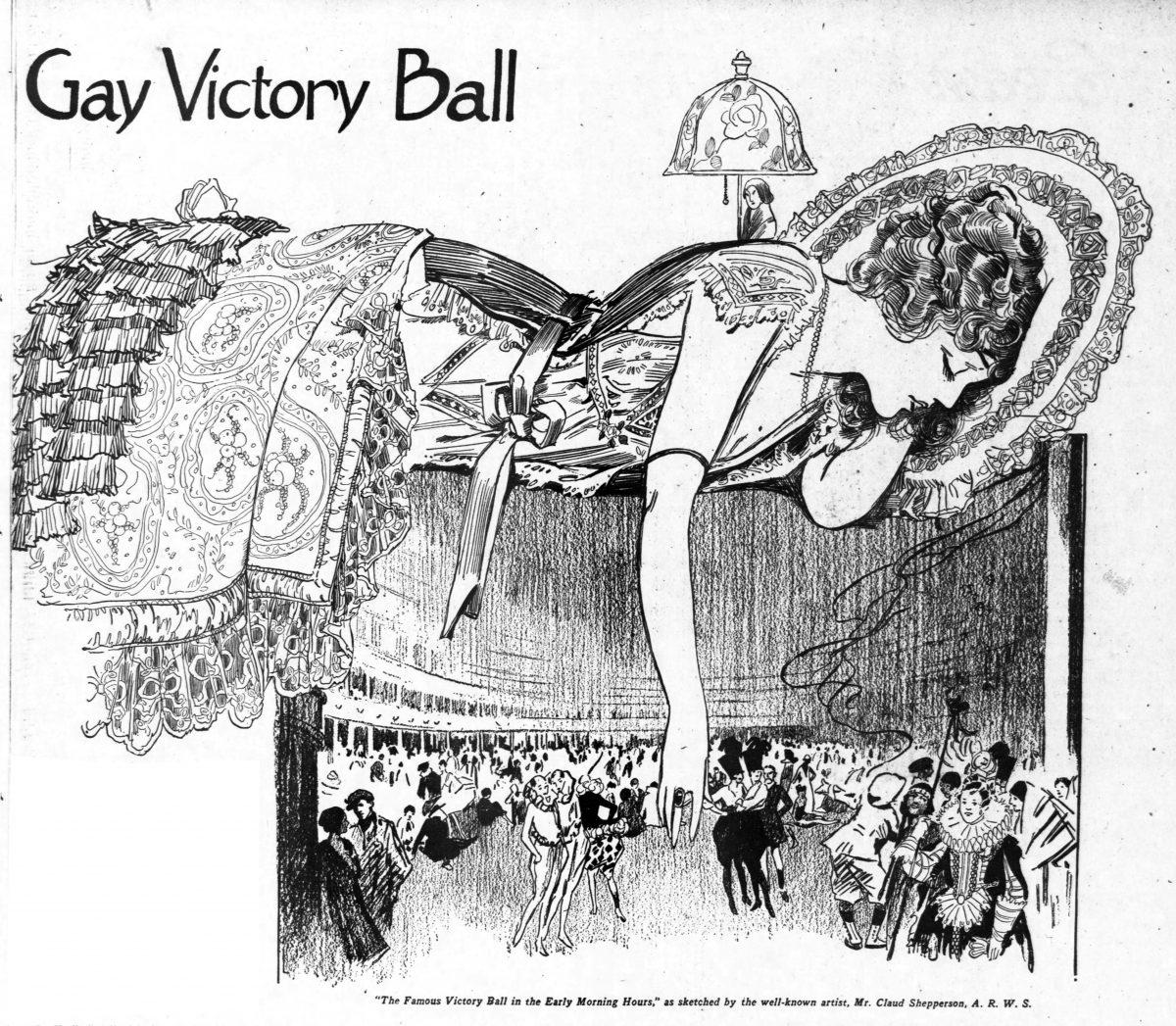

On 27 November, with coloured bunting celebrating the end of the Great War still fluttering between lamp posts all over London, the Great Victory Ball was held at the Royal Albert Hall to celebrate the recent Armistice. It was essentially a huge fancy-dress party, or as one American newspaper put it ‘a mad revel in which London relieved its emotions after four years of pent-up agony’. The evening was also to celebrate women’s achievement during the war, with all the proceeds going to the Nation’s Fund for Nurses. The event was sponsored by the Daily Sketch, which agreed to pay all expenses and trumpeted:

Today, women of the Allied nations take part in the festival of victory as a right. They have earned that right in hospitals at home and abroad; in the fields as labourers ploughing and garnering the grain; in the workshops turning out shells; in the towns doing men’s work; in the homes suffering in silence.

Thousands of people attended the ball, with the Albert Hall decorated throughout with blue and white flags in tribute to the nurses, who that evening mingled on the dance floor with guardsmen in scarlet dress uniforms. At one point, to the strains of Elgar’s Pomp and Circumstance March No. 1 in D, a composition performed for the first time just seventeen years previously, a grand procession entered the hall led by Lady Diana Manners dressed as ‘Britannia’, wearing classical draperies with a plumed helmet and trident. Next to her was the Duchess of Westminster representing ‘England’ in white robes and the ‘old red cross of St George on her bosom’, while the Countess of Drogheda, one of the first female pilots, was, rather aptly, ‘Air’. Just before midnight, as the characters grouped together before the organ, ‘Rule Britannia!’ was played and the whole concourse of guests sang it in unison. Dancing then continued until the early hours.

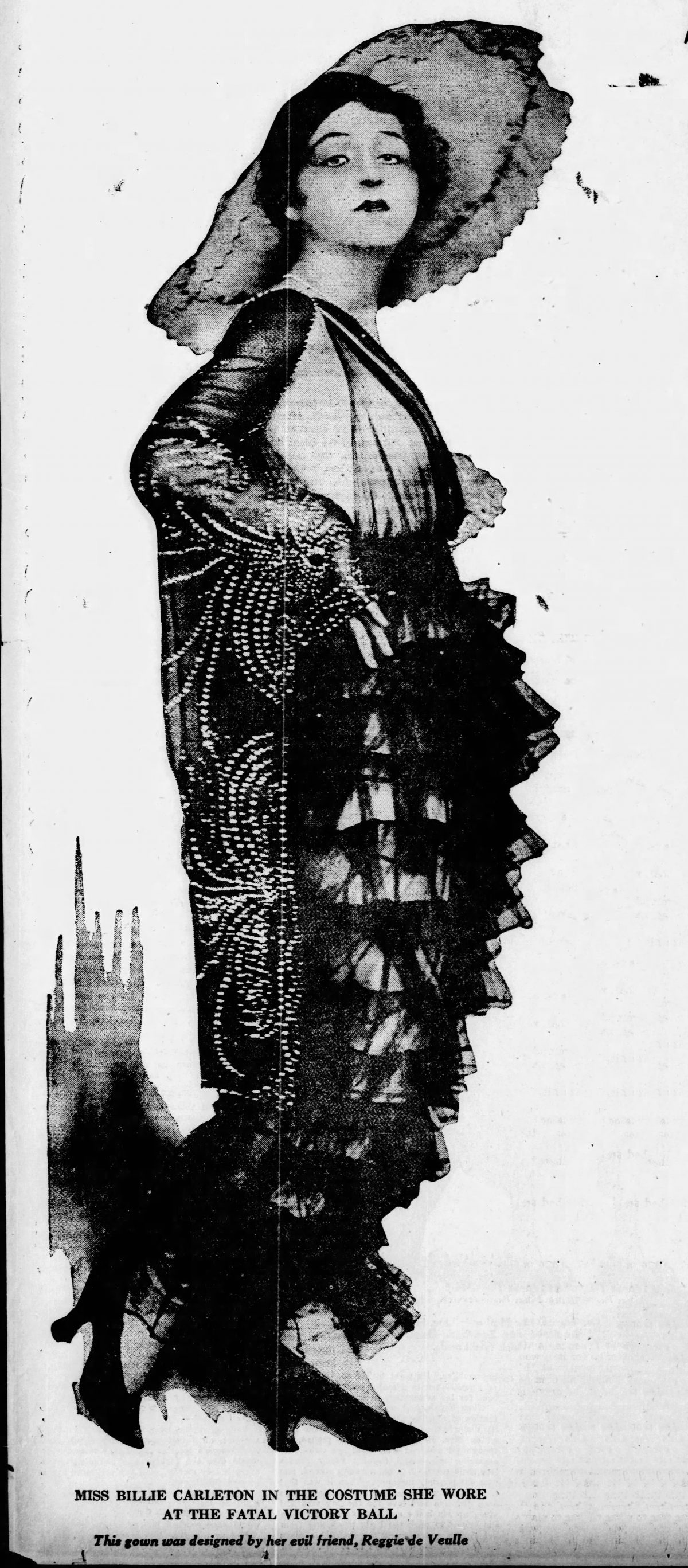

An excited, vivacious Billie Carleton was at the ball and standing out from the crowd, not least because of her eye-catching dress designed by her friend and opium party host Reggie de Veulle. One newspaper described it as ‘extraordinary and daring to the utmost, but so attractive and refined was her face that it never occurred to any one to be shocked. The costume consisted almost entirely of transparent black georgette which revealed the flesh beneath to an extreme degree – to the limit in fact.’ Carleton was still performing in The Freedom of the Seas, which had been running since August, and she was currently fêted as the youngest leading actress in the West End. Although many contemporary reviewers spoke of her relatively modest talent and often noted her weak voice, she was pretty, with an impish smile, and was well-loved by the London theatre audiences. A few months earlier, Tatler magazine had reviewed one of her performances, saying that she had ‘Cleverness, temperament and charm. Not enough of the first, and perhaps too much of the latter.’

Dennis Eadie and Billie Carleton in Freedom of the Seas at the Haymarket Theatre, 1918

Earlier that evening Carleton had received two visitors in her Haymarket Theatre dressing room. One was a middle-aged Italian officer, Jianni Bettini, who had been staying at the Savoy Hotel and had recently been taking her out occasionally. She had called him to visit her solely to show off – presumably without an objection on his part – her diaphanous Victory Ball costume. The other visitor, Carleton’s personal maid May Booker, had, as asked, brought her mistress’s Dorothy bag to the theatre, inside which was a little jewelled gold box. Carleton was no longer staying at the de Veulles’ in Dover Street, but had moved just over half a mile away from the theatre to Savoy Court Mansions – an expensive serviced apartment block just behind the Savoy Hotel. Her new home was courtesy of another middle-aged gentleman friend called John Darlington Marsh – a rich Edwardian playboy whom she had known since she was about sixteen. He had kept her financially solvent ever since – very financially solvent. Marek Kohn in his must-read book Dope Girls writes that, courtesy of Marsh, Carleton had £5,000 (the equivalent of about £250,000 as of 2017) in her bank account, despite never earning more than £25 per week. Earlier that day, also courtesy of Marsh, she had redeemed from a pawnshop at the cost of £1,050 (although it was worth twice as much) some beautiful jewellery to wear for the ball. The average weekly wage for a woman at the time was about £2.

Before setting off to the Albert Hall, Carleton had supper with another of her gentleman friends, a man called Frederick Stuart, a Knightsbridge doctor. Carleton, who had never known her father, relied heavily on men in her life, most of whom were twenty or thirty years her senior, although no one really knows how intimate these relationships were. Stuart, like Marsh, had known Carleton since she was fifteen or sixteen and was not only her physician but also, somewhat dubiously, looked after her financial affairs. Accompanying Carleton and Doctor Stuart that evening was her friend the actress Fay Compton (sister of Compton Mackenzie, author of Whisky Galore and co-founder of the SNP) who, despite being married to the actor and comedian Lauri de Frece – her second husband – was being escorted that evening by Lieutenant Barraud, a fellow actor and not long home from the front.

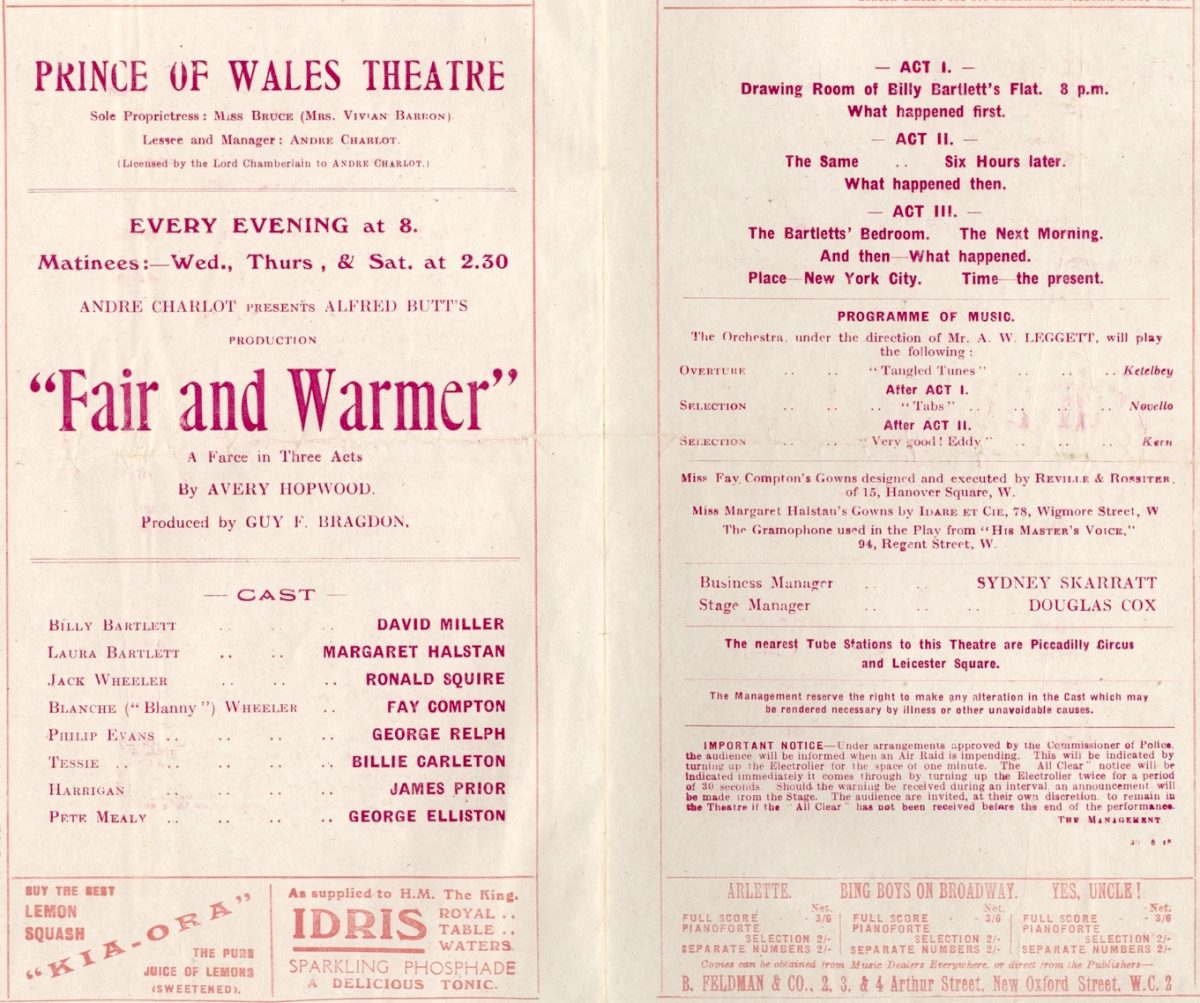

The programme for Fair and Warmer at the Prince of Wales Theatre – note the Air-Raid warning bottom right.

Fay Compton

Carleton and Compton were close friends and a few months earlier had performed together in Fair and Warmer, a comedy by Avery Hopwood at the Prince of Wales Theatre, where Carleton played Tessie the maid to Fay Compton’s ‘flapper’ character. After supper the foursome took a taxi (which had been paid for the whole day by the extravagant Carleton) to Kensington Gore and the ball at the Albert Hall. Carleton was reported by one newspaper to have ‘thrown herself with somewhat feverish energy into the affair and danced again and again. It seemed that every man there wished to dance with her!’ At one point she met up with de Veulle, who was dressed in a Pierrot outfit which he had designed himself. Displeased that he had found himself at a ‘dry’ event, he told her that he was ‘off to sniff some snow’, and Carleton almost certainly followed suit. Another of her friends was at the ball – Irene Castle, a famous American dancer and currently a neighbour in the Savoy Court apartment block. With her late English husband Vernon, Irene had refined and popularised the foxtrot on Broadway and from about the time of their marriage in 1911 they were probably the most popular and influential dance partners in the world. They were interesting characters and in many ways particularly modern in their outlook: they travelled with a black orchestra, had an openly lesbian manager, and the trendsetting Irene bobbed her hair a decade before the flapper look of the 1920s.

Irene Castle by Edward Thayer Monroe

After the peak of their extraordinary celebrity, Vernon had joined the Royal Canadian Flying Corps in 1916 and served in France, but was killed in February 1918 after a flying accident in Fort Worth, Texas. Irene had recently arrived in England to appear in a film for the Red Cross, and was already a movie star of sorts (she would appear in more than a dozen films between 1917 and 1922). She was a guest of the American portrait painter and set designer Ben Ali Haggin and was dressed in a Persian boy outfit he had designed for her: ‘If I do say it myself, I wore the most beautiful costume there. It was gorgeous. It cost two thousand dollars,’ she later wrote to a friend, recalling that the ball was ‘one of the most joyous and dazzling I’d ever seen’. A newspaper reported that the Victory Ball ‘grew into a wild night. The end of four years of the greatest slaughter in history demanded relief for overstrained nerves, an outlet for pent-up emotions.’

At around three in the morning, when the Victory Ball was coming to a close, Carleton left the Albert Hall with her taxi full of friends. Fay Compton and her uniformed lieutenant were dropped off nearby on Hereford Square in Kensington, as was Doctor Stuart in Knightsbridge soon after. Continuing back to Savoy Court Mansions with Carleton was a cinema actor called Lionel Belcher, who was married but accompanied by his live-in lover, Olive Richardson. Belcher was also Reggie de Veulle’s cocaine dealer and usually obtained the drug, along with heroin, from a Soho chemist in Lisle Street behind the Empire Theatre. When the taxi arrived at Savoy Mansions Carleton paid the taxi driver £3 for his day’s work and, before they all squeezed into the tiny lift up to her apartment, she confirmed with the concierge that Irene was back from the ball. The American actress and dancer was still known as Mrs Vernon Castle, although she had secretly remarried earlier in the year, three months after Vernon’s plane crash. Carleton ordered breakfast of bacon and eggs for everyone although before it arrived she went across to Irene’s apartment to give her a close-up view of her jewellery and her beautiful translucent gown.

Years later Castle, wary of the press after they had given her a hard time when her secret and all-too-swift remarriage was uncovered, was very keen to extricate herself from any drug-taking rumours about that evening. She later wrote that she and Billie had done nothing but ‘play dress-up’ while Carleton told her how apprehensive she was about plans to go to Hollywood, to which Irene replied, ‘You’ll be wonderful there. They love blondes.’ Using perhaps the wrong simile, at least as far as Carleton was concerned, the brief time the two dancing actresses spent together was once described as ‘innocent as a teenager’s pyjama party’. After returning to her apartment, Billie changed into a kimono, got into bed and, while eating her bacon and eggs, happily talked of her hopes and dreams, including the planned trips to America and Paris. At about six in the morning, Lionel and Olive’s taxi arrived, and they turned off the lights as they left. Lionel Belcher would later say, ‘We left Miss Carleton in bed, perfectly well and extremely bright!’

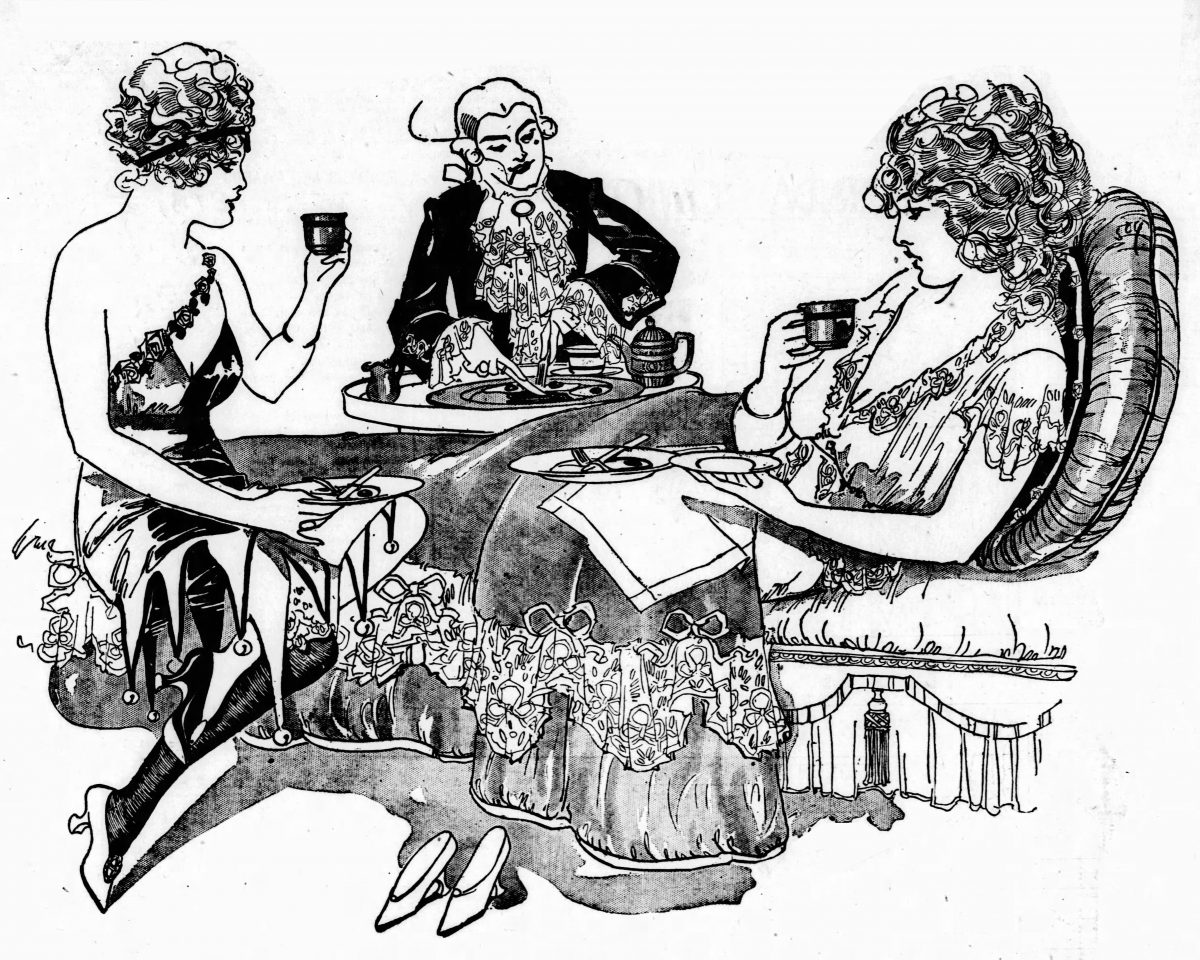

Belcher, Olive Richardson and Carleton still in their costumes eating Breakfast at Carleton’s Savoy Mansions serviced flat.

Unfortunately there were no trips to California or France, and Billie Carleton’s fame, such as it is, has more to do with the way she died than for any of her stage successes. The girl with too much charm and a daring costume was found dead in her bed that afternoon. On the dressing table next to her was a little jewelled gold box, half full of cocaine. Her maid had arrived at about 11.30 that morning and heard loud snores from her mistress’s bedroom. She was used to Carleton’s frequent late nights and left her alone. About four hours later, after getting no response, she found Carleton lying on her side seemingly sleeping. There were discarded clothes all over her bed and her face looked very pale.

Booker tried to wake her mistress, but it was to no avail and she called Carleton’s friend Doctor Stuart. When Stuart arrived, he gave Carleton artificial respiration and injected her with brandy and strychnine, but it wasn’t long before he had to pronounce her dead. Stuart then noticed some sachets of Veronal (a barbiturate used for sleeping) in the bedroom and initially placed them in his pocket. The hotel manager noticed the sachets missing and Stuart, admitting that he had taken the Veronal, placed them back where he found them. The police surgeon soon arrived and noted that Carleton’s pupils were widely dilated, there was a stain on the side of her mouth, ‘as if of something trickling out’, and the skin underneath the fingernails of the left hand was blue. The youngest leading actress in the West End had died aged just twenty-two.

Billie Carleton was the daughter of chorus singer Margaret Stewart, and was born on 4 September 1896 in Bernard Street in Bloomsbury – the road on which Russell Square Underground station opened ten years later. Christened Florence Leonora Stewart, she chose the name with which she became famous when she left school at fifteen to go on to the stage. It was the theatre impresario Charles B. Cochran who gave the nineteen-year-old Carleton her first big break in November 1915 when as an anonymous chorus girl in Irving Berlin’s Watch Your Step at the Empire Theatre in Leicester Square he asked her to play Stella Sparkes, one of the leading roles. It’s Carleton’s voice on the London cast recording singing Show Us How to Do the Fox Trot with George Graves. Watch Your Step was actually Berlin’s first complete musical, and he became the first Tin Pan Alley composer to move ‘uptown’ to Broadway when it opened at the New Amsterdam Theatre in December 1914 – a production, coincidentally, that starred Mr and Mrs Castle, with Irene playing the Stella Sparkes role.

A fresh faced 19 year old Carleton in Watch Your Step

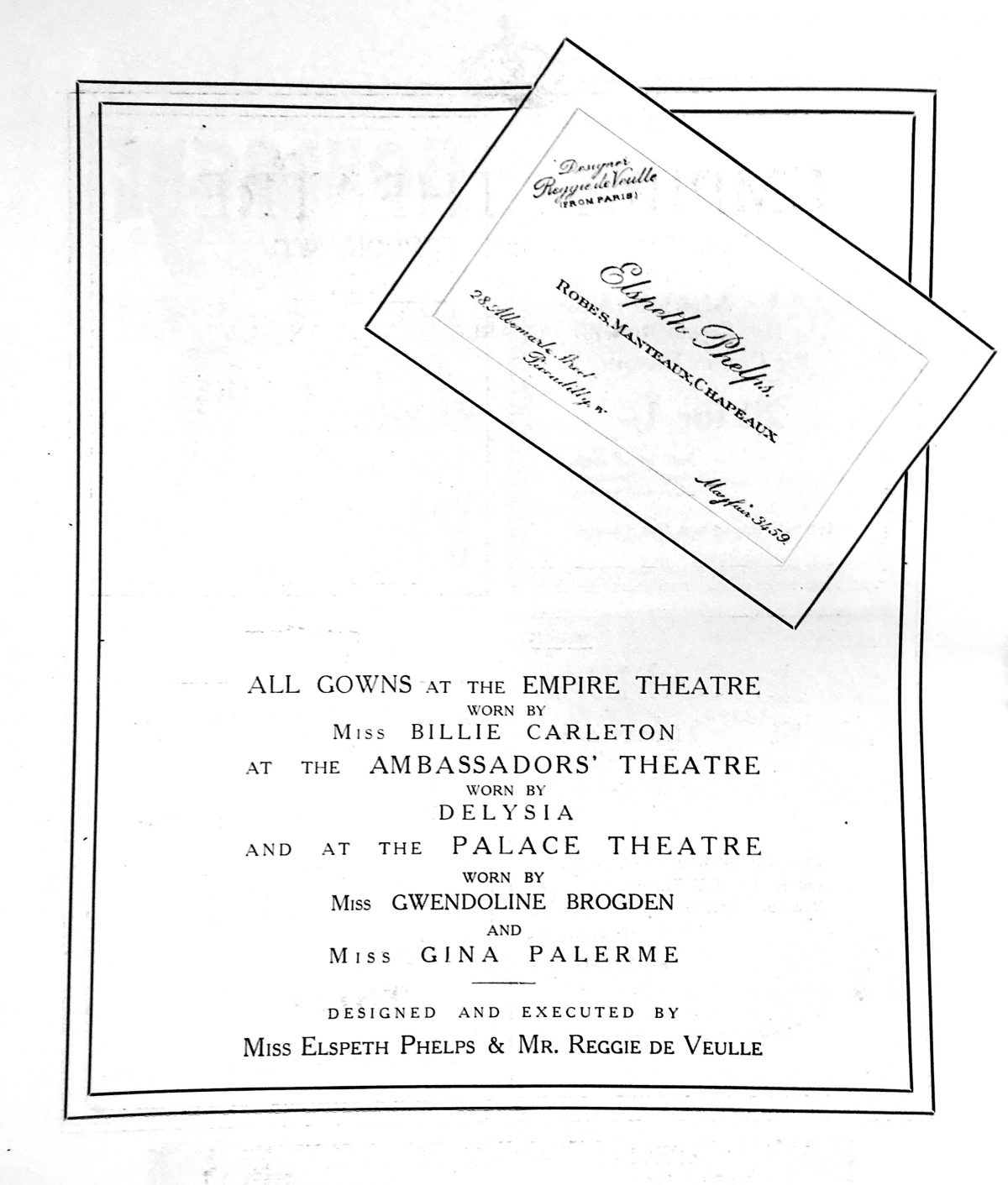

Watch Your Step Elspeth Phelps ad

Opposite the cast list in the Watch Your Step Empire Theatre programme, Reggie de Veulle’s name appears in an advert for Elspeth Phelps. Before he moved to Hockley’s, he had worked for the prestigious costumier based in Albemarle Street and had designed all of Carleton’s gowns for the show. For a year or so previously Carleton had been supplementing her theatre wages by modelling de Veulle’s confections of tulle and lace.

Cochran later remembered Carleton’s debut as a leading actress, writing:

Despite her inexperience and her tiny voice, she pleased the audiences. A more beautiful creature has never fluttered upon a stage. She seemed scarcely human, so fragile was she.’ During the run of Watch Your Step, however, he soon found out she ‘was being influenced by some undesirable people and was going to opium parties.

He fired her but he liked her and soon gave her another chance when she appeared in his production Houp La! at St Martin’s Theatre. She made little impression and only appeared for one week before the production had to close.

Billie Carleton

Carleton was then taken under the wing of André Charlot, the chain-smoking French impresario who insisted that everyone called him ‘Guv’ and who never quite lost his Maurice Chevalier accent. He was infamous for pursuing the girls, of which there were dozens and dozens, whose names he put up in lights, but he was responsible for some of the best revues in London that were tasteful, lively and described as ‘with it’. Charlot put Carleton in a revue called Some More Samples! at the Vaudeville Theatre on the Strand. The Canadian actress and comedienne Beatrice Lillie, then twenty-one, was performing in the same show, and Charlot was driven mad by the constant laughing and joking by the two women. During one performance Lillie came on stage sporting an unrehearsed big false moustache wiggling under her nose.

The audience giggled but Charlot didn’t, and the following morning there was a note on the noticeboard by the stage door: ‘BEATRICE LILLIE FINED FIVE SHILLINGS FOR TRYING TO BE FUNNY.’ During one scene entitled ‘The Nursery’, the children were played by Carleton, Lillie and future star Gertrude Lawrence in her first West End appearance. In her autobiography Lillie would later recall that they would often run into the Strand to watch the Zeppelins, which she described as being ‘like silver fish in the night sky, flying up above the Thames’. The description was poetical, but when the German airships started dropping bombs it was the first time that Londoners realised they were no longer invulnerable to foreign-based wars.

At about the time Carleton was performing in Watch Your Step, the Daily Mail was noting that for many young women it was a changing world, especially in wartime London. The newspaper called them the ‘Dining Out Girls’ and was actually quite celebratory in tone about this modern, liberated woman who could be seen most nights:

dining out alone or with a friend in the moderate price restaurants in London. Formerly she would never have had her evening meal in town unless in the company of a man friend. But now, with money and without men, she is more and more beginning to dine out.

In her memoir How We Lived Then – 1914–18, Mrs C. S. Peel noticed how Soho was becoming a part of London where anyone, including single young women, might venture: ‘Life was very gay,’ said one young woman in Mrs Peel’s book. ‘It was only when someone you knew well or with whom you were in love was killed that you minded really dreadfully. Men used to come to dine and dance one night, and go out the next morning and be killed. And someone used to say, “Did you see poor Bobbie was killed?” It went on all the time, you see.’ These young single women, modern and independent, had started to be called ‘flappers’ in England (the word wouldn’t become popular in America until a few years later in the twenties) and in August 1917, in a popular play called The Boy at the Adelphi, Carleton played an ‘up-to-date flapper’ called Joy Chatterton. Tatler described her as ‘one of the most vivacious soubrettes on the musical- comedy stage, and has a droll method which is all her own’. The slang word ‘flapper’ has several possible derivations or sources – a description of a young bird flapping its wings while learning to fly, an earlier use in northern England to mean ‘teenage girl’ (referring to hair not yet put up and whose plaited pigtail ‘flapped’ on her back) or an old English word meaning ‘prostitute’.

Whether you were an independent woman or not, it was becoming far harder, courtesy of the government, to buy an alcoholic drink during the First World War. Before the notorious Defence of the Realm Act, ‘affectionately’ called DORA and enacted without debate four days into the war, Londoners could drink almost when they liked. Pubs would open at 5.30 in the morning and not close until nineteen hours later at half past midnight. The new opening hours (most of which lasted until 1988! And in some aspects still exist today) were from 12 noon to 2.40 p.m. and 6.30 p.m. to 10 p.m. The new law didn’t stop there; it became illegal to buy a round and, in fact, a drink for anyone but yourself (the ‘no treating order’).

Initially the new law allowed restaurants and clubs to be open until 10.30 p.m. but this was soon brought forward to only 9.30 p.m. Subsequently the number of illegal nightclubs escalated profusely – by the end of 1915 Kohn in Dope Girls states that there were 150 or so illegal clubs in Soho alone. Mrs Peel wrote: ‘The growth of the night club was an outstanding feature of war-time life. Such places had always existed but it was not until after war was declared that they were patronised by women and young girls of good reputation.’ Although drinking late into the evening was now illegal, the ‘Beauty Sleep’ order, as it was often called, never prevented the illicit sale of food and drink. Restaurants and nightclubs served spirits in coffee cups and champagne was disguised as lemonade. The order, however, undoubtedly encouraged other forms of illegality to proliferate – especially drugs. In January 1916 the Evening News columnist Quex spoke of ‘dark stories’ in ‘West End Bohemia’ and the prevalence of ‘that exciting drug cocaine’: ‘It is so easy to take – just snuffed up the nose; and no-one seems to know why the girls who suffer from this body and soul racking habit find the drug so easy to obtain.’

In 1916 it was well known to many of her associates that Carleton was taking drugs. One friend of hers said that the knowledge ‘was rather public property’. Carleton was probably introduced to cocaine and opium either by an American man called Jack May (his real name was Gerald Walter) or an odd character called Captain Ernest Schiff. May was the manager of Murray’s Cabaret Club on Beak Street, which had opened just before the war and which was owned for most of its long life by Percival ‘Pops’ Murray, and subsequently by his son David (it was where Christine Keeler and Mandy Rice-Davies met while working there some forty years later). A customer during the First World War once claimed that ‘cocaine was what people came to Jack May’s club for. It was slipped to you in packets, very quickly, when you coughed up the loot.’

Jack May and Billie Carleton (right) at Murray’s Day Club

In June 1915, Jack May is seen with an eighteen-year-old Billie Carleton in a photograph taken at Murray’s Day Club in Maidenhead for Tatler magazine. May was also mentioned in a letter by the Eton-educated Captain Schiff who in December 1915 wrote to the Attorney General, Sir John Simon: ‘A very bad fellow, Jack May, is the proprietor of Murray’s Club in Beak Street – a quite amusing place. But for vice or money or both he induces girls to smoke opium in some foul place. He is an American and does a good deal of harm.’ Although the description was not inaccurate, the disingenuous Schiff wrote it to cover his tracks. As one biographer wrote of Schiff: ‘It was rare a dope party was held in Soho that he failed to attend.’ Born of naturalised Austrian parents, Schiff was an habitual gambler, pimp and blackmailer and was said, despite a commission in the Royal Sussex Regiment, to have supported Germany during the war. He had the strange Teutonic habit of filing his fingernails to a point and Empire News once wrote that Schiff ‘invariably took his soup in the noisy fashion in the “art” of which the Hun stands supreme’. Captain Schiff and Horatio Bottomley, almost certainly, were no great friends.

The time was ripe for a moral panic, and in February 1916 cocaine was again mentioned in the newspapers when Horace Kingsley, an ex-soldier and ex-convict, and Rose Edwards, a London prostitute, were each given six months’ hard labour for selling cocaine to Canadian soldiers at a military camp in Folkestone. The day after the verdict, the Times’ medical correspondent came down hard on the drug: ‘Cocaine is more deadly than bullets,’ he wrote – an extraordinarily crass thing to write when in the preceding month alone about 10,000 British men had perished on the Western Front, many by bullets. The ignorant stupidity continued when he added that ‘most cocainomaniacs carry a revolver to protect themselves against imaginary enemies’. A few days later an H. C. Ross wrote to the same newspaper about ‘small silver matchboxes’ he had seen in well-known West-End jewellers that were designed to be sent to friends and loved ones on the front and which contained three tubes filled with tablets of morphine hydrochloride, to be taken when severely wounded. The letter concluded, ‘Morphiomania is a terrible malady.’ Which indeed it is, but possibly not of undue concern to a soldier who has just had his leg shot off.

The Times, ironically, had recently been carrying advertisements for preparations of morphine and cocaine by Harrods and Savory & Moore (Mayfair chemists and suppliers to King George V), describing them as a ‘useful present for friends at the front’. In February 1916, both stores were found guilty of selling morphine and cocaine contrary to restrictions contained in the 1908 Poisons and Pharmacy Act. The prosecutor, Sir William Glyn-Jones, secretary of the Pharmaceutical Society and practising barrister, made a point of saying that it was an ‘exceedingly dangerous thing for a drug like morphine to be in the hands of men on active service … it might have the effect of making them sleep on duty, or other very serious results’. Both Harrods and Savory & Moore were fined, albeit nominal amounts. In July 1916 Regulation 40B of the Defence of the Realm Act came into effect, which criminalised the possession or sale of opium or cocaine by anyone except licensed chemists, doctors and vets. Further domestic legislation followed after the war when the Treaty of Versailles contained a clause requiring signatories to introduce domestic drugs legislation. In Britain this evolved into the Dangerous Drugs Act 1920; this Act changed drug addiction to a penal offence, though up to then, within the medical profession, it had been treated as a disease.

Carleton’s death, seemingly of cocaine, and the subsequent inquest and court cases often featured on the front pages until April 1919, and both The Times and the Daily Express used the case as an excuse to run an investigation into London’s illicit drug trade. The long inquest at Westminster Coroner Court, presided over by the coroner Samuel Ingleby Oddie, began one week after the tragedy, and consisted of five sittings through December and into late January. Even though the inquest started at 2.30 p.m., crowds often convened outside the court from seven in the morning, eager to catch some of the highly publicised proceedings. It was often reported that well-known actresses were in the public gallery, but no names were mentioned. The first witness was Mrs Katherine Jolliffe, an aunt of Carleton’s who had identified the body and confirmed that the deceased had no living parent when she died. She also identified to Mr Oddie the small, exquisitely jewelled gold box as belonging to Carleton. Another early witness was May Booker, Carleton’s maid, who confirmed that she had taken her mistress’s gold box to the theatre. The coroner asked her, ‘Was there any white powder in it?’ ‘No,’ she replied. Booker then described the scene when she came to Savoy Court the next day and tried to wake Carleton, and Oddie asked if she had seen the little gold box in the bedroom. Booker replied: ‘Yes, when I looked in the box there was some white powder. It was like sugar stuff. I had never seen powder like that before. I did not know my mistress took drugs.’ Next on the witness stand was Lionel Belcher, looking, as someone once said, far more handsome than his name would suggest. The actor had appeared recently with Mrs Patrick Campbell’s Mystery of the Thirteenth Chair theatre company, and had a major role in the film Yoke the year before. The witness dodged and denied any insinuations that he or de Veulle were engaged in procuring prohibited drugs for Miss Carleton or anyone else. For an actor, Belcher was a bad liar and it was apparent to everyone in the court that he was avoiding the truth. Mr Oddie then adjourned the hearing until 12 December, when he empanelled a jury.

After the adjournment Belcher was questioned again, but this time, after a consultation with his solicitor and a voluntary visit to the police, his memory started to improve and he started telling something closer to the truth about his drug-taking habits. At one point Belcher nonchalantly admitted that he was ‘more addicted to heroin than anything else’ (heroin was not covered under DORA 40B) but also admitted selling cocaine to de Veulle at an inflated price – ‘I don’t look upon it as any more despicable than selling a bottle of whisky at an over-charged rate, after time’ – to which there was audible concurrence from the viewing galleries. The actor then spoke about procuring cocaine in Chinatown from a house on Limehouse Causeway, and said that a ‘Chinaman named Lo Ping You’ supplied it. At the mention of Chinatown and Limehouse, the ears of the reporters pricked up.

Not that they really needed one, but this gave the newspapers an excuse to write about the encroaching so-called ‘Yellow Peril’ – a phrase credited to the Edwardian writer M. P. Shiel, who put Limehouse on the literary map in 1899 with his novel The Yellow Danger, about a Chinese gang that invades London. The scandal around Billie Carleton encouraged dozens of stories in the popular press over the next two or three years. In reality the English ‘yellow peril’ was actually a small, relatively law-abiding Chinese community which had been based around the Limehouse docks area, probably from around the beginning of the nineteenth century. At the start of the twentieth century there were two separate communities in the area – the Chinese from Shanghai, who were based around Pennyfields and Ming Street (between the present Westferry and Poplar DLR stations) and the immigrants from Southern China and Canton, who lived around Gill Street and the Limehouse Causeway. By 1911 the whole area had started to be called Chinatown by the rest of London.

In 1920 the Evening News headlined a story ‘White Girls Hypnotised by Yellow Men’, and wrote that it was the duty ‘of every Englishman and Englishwoman to know the truth about the degradation of young white girls in this plague of the Metropolis – IT MUST BE STOPPED’. The Daily Express at the same time had the front-page headline ‘Yellow Peril in London’ and wrote: ‘A Chinese syndicate, backed by millions of money and powerful, if mysterious, influences, is at work in the East End of London. Its object is the propagation of vice.’ Women treated by the Chinese in ways that were left to the reader’s imagination, were described as victims of this international drugs and gambling syndicate:

White Englishwomen seem to exert a remarkable fascination for them. But the white women who fall into the clutches of the “yellows” are not Londoners, but mainly come from provincial inland towns. They are without exception young and pretty, but in what manner they are attracted to the Chinese quarter of London has not been unravelled.

Considering that there were rarely more than a few hundred Chinese people living around Limehouse before and after the First World War, the East End Chinatown had an extraordinarily bad reputation, even internationally. An overexcited Washington Times played on the exaggerated fear Americans had of their own Chinatowns and wrote that Carleton’s friends took her to Limehouse ‘to indulge in more fantastic and brutal orgies when the comparatively refined opium parties in West End flats were beginning to pall’. The newspaper continued:

Limehouse is perhaps the most grimly, gruesomely wicked quarter in the whole world. It is far to the east of the Strand, east of the Tower of London, lost in the purlieus of London’s darkest east. The Causeway is the principal thoroughfare in this sink of iniquity, raised centuries ago above the mud flats of the Thames. Limehouse is the ‘Chinatown’ of London, but it contains among its swarming thousands specimens of many races besides the Chinese. It has become an Oriental quarter through the proximity of the vast East India docks. Many opium smoking dens are kept in Limehouse by Chinamen. Their chief customers are Oriental sailors and dock labourers, commonly called Lascars in London parlance. With them, too are many sailors of other nationalities, together with an assortment of criminals, dock rats and dregs of society of both sexes. Here, too come persons from the higher strata of society, who have exhausted the pleasures of West End resorts and yearn for stranger and more brutal forms of dissipation.

Sometimes it seemed that Limehouse was almost solely to blame for corroding the moral backbone of the entire British middle class. It wasn’t just the fault of a slavering press with its lurid headlines of opium dens and traders in white slaves, however; there were also numerous writers, novelists and even filmmakers who helped exaggerate the danger and immorality of the area. H. V. Morton, the famous travel essayist and journalist, wrote about Limehouse in his book The Nights of London:

The squalor of Limehouse is that strange squalor of the East which seems to conceal vicious splendour. There is an air of something unrevealed in those narrow streets of shuttered houses, each one of which appears to be hugging its own dreadful little secret… you might open a filthy door and find yourself in a palace sweet with joss-sticks, where queer things happen in a mist of smoke … The silence grips you, almost persuading you that behind it is something which you are always on the verge of discovering; some mystery of vice or of beauty, or of terror and cruelty.

The fact that the Chinese community liked to gamble and smoke opium was bad enough, but it was the fear of sexual contact between the races (which the drug taking of course only exacerbated) that frightened so many people. Thomas Burke, writing for an apprehensive suburban readership that lapped up his writings, even in the US, wrote a number of ‘sordid and morbid’ short stories and newspaper articles, owing much to Jack London, about the Limehouse Chinatown. One of his stories, from a collection entitled Limehouse Nights (which was banned for immorality by the national subscription libraries run by Boots and WH Smith), was called The Chink and the Child and was made into a successful film entitled Broken Blossoms, or the Yellow Man and the Girl by D. W. Griffith that starred Lilian Gish.

Broken Blossoms with Lilian Gish

Another of the stories from Limehouse Nights was called Tai Fu and Pansy Greers and was about a young white woman who submitted herself to a ‘loathly, fat and old’ Chinese man:

He was a connoisseur, and used his selected yen-shi (opium) and yen-hok (a needle used to cook the opium pellet) as an Englishman uses a Cabanas. The first slow inhalations brought him nothing, but, as he continued, there would come a sweet, purring warmth about the limbs … She went to him that night at his house in the Causeway. He opened the door himself, and flung a low-lidded, wine-whipped glance about her that seemed to undress her where she stood, noting her fault and charm as one notes an animal. He did not love her; there was no sentiment in this business. Brute cunning and greed were in his brow, and lust was in his lips … What he did to her in the blackness of that curtained room of his had best not be imagined. But she came away with bruised limbs and body, with torn hair, and a face paled to death.

Sax Rohmer, born in the south London suburbs in 1883 as plain Arthur Ward, was another former journalist who used Limehouse myths as inspiration to write popular fiction. He wrote the incredibly successful Fu Manchu novels, about a depraved Chinese man whose evil empire’s headquarters was based, improbably, in Limehouse:

Imagine a person, tall, lean and feline, high-shouldered, with a brow like Shakespeare and a face like Satan, a close-shaven skull, and long magnetic eyes of the true cat-green. Invest him with all the cruel cunning of an entire Eastern race, accumulated in one giant intellect … Imagine that awful being and you have a mental picture of Dr Fu Manchu, the yellow peril incarnate in one man.

Myrna Loy camera negative from The Mask of Fu Manchu by Clarence Sinclair Bull.

Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu stories went on to inspire over thirty films and television series throughout the following decades (even a brand of sweets, sold until the 1970s, was called Fu Man Chews). Rohmer, unashamedly cashing in on the Carleton scandal, also wrote a novel called Dope, in which a character called Rita Dresden was based on Billie Carleton. A silly socialite called Mollie Gretna in the same novel envies the Scottish wife of a Chinese drug dealer (based on Ada and Lo Ping You):

Oh! Mollie’s eyes opened widely. ‘I almost envy her! I have read that Chinamen tie their wives to beams in the roof and lash them with leather thongs. I could die for a man who lashed me with leather thongs. Englishmen are so ridiculously gentle to women.’

On 20 December 1918 at Marlborough Street Police Court (presided over by seventy-one-year-old Frederick Mead, who had been called to the bar in 1869 and who was as Victorian in his outlook as his Dickensian side-whiskers, Ada Ping You was the first to be sentenced during the legal aftermath of Carleton’s death. While Billie Carleton’s inquest was still ongoing, Ping You was charged, under Regulation 40B of DORA, with possession and supplying opium and cocaine to the late actress, and also for preparing opium at Mr and Mrs de Veulle’s Dover Street flat. Of the two charges Ping You pleaded guilty only to the latter. Mr Muskett, for the prosecution, said that he wanted to present the facts in as colourless a manner as possible and was determined to avoid any unnecessary sensationalism. He took no notice of himself, however, and immediately called the story ‘sordid’, ‘squalid’ and ‘deplorable’ and thought everyone would agree that it was ‘a disgrace to modern civilisation’. In his closing statement, Frederick Mead, who was not known for his leniency, said that Ping You played a leading part in the ‘disgraceful orgy’ and that she was ‘the high priestess at these unholy rites’. He gave Ada Ping You the harshest sentence possible – five months of hard labour. She was already ill when she was sentenced, and, after a tough stint at Holloway Prison, died of tuberculosis in 1920.

Marek Kohn, in his book Dope Girls, says of Ada Ping You that ‘while there had been a tradition of tolerance towards opium use by the introverted Chinese community as long as it didn’t affect the indigenous population, a woman crossing the East–West divide to bring the foreign drugs to Mayfair was quite a different story’. The tolerance to the Chinese community was shown in another court where Ada’s husband Mr Ping You (arrested at the same time as his wife at their Limehouse residence where a small amount of opium was found) was fined just £10.

During the inquest, the influence of Carleton’s middle-aged male ‘friends’ had over her was acknowledged but little criticised – except in the case of Reggie de Veulle, the man with the effete name, effete manner and effete job. He faced nothing less than a continual character assassination. One newspaper described him as ‘a strange, sallow, very well dressed, effeminate little man, who hovered about her [Carleton] with deadly persistence’, while the Daily Telegraphwrote of his ‘effeminate face and mincing little smile’. Reginald de Veulle was the son of a former British vice-consul and French mother and was born in France but brought up in Jersey. Lionel Belcher’s counsel, Cecil Hayes, was particularly keen to deflect any blame from his client and direct it towards de Veulle. ‘How long have you been engaged in the gentle art of designing ladies’ dresses?’ he asked, and then followed with, ‘I put it to you that while your youth lasted you often made curious friendships with older men?’ De Veulle responded, ‘Has that anything to do with this case at all?’ Mr Hayes continued: ‘I believe these curious friendships that you made with older men were sometimes very paying, were they not?’ De Veulle pretended not to understand the question, but Hayes was not to be deflected from his line of questioning. ‘Were some friendships with men much older than you very remunerative for you?’ De Veulle admitted to the court that he had once been given money as a young man by William Cronshaw, by whom he had been employed as a ‘gentleman’s secretary’. Before the First World War de Veulle had had been involved in a homosexual blackmail case and William Cronshaw, to allay suspicions, had paid de Veulle to leave the country. Reggie travelled to America where he found jobs acting and performing. He was fortunate perhaps that Mr Hayes, Belcher’s counsel, hadn’t access to American newspapers. One gossip column in the Chicago Tribune described de Veulle as a guest of honour at a supper party where he had showed off his ‘naughty wiggly dance in The Queen of the Moulin Rouge (a musical he had been touring in) and who had recently been “pinched” for so doing’.

Malvina Longfellow, a twenty-nine-year-old American actress, who had lived in London after marrying a British officer, was also called as a witness. The photographer E. O. Hoppé, who was happy to consider himself a connoisseur of this sort of thing, once called her one of the most beautiful women in the world, and she had recently played Lady Hamilton in the film Nelson. Longfellow testified that she knew of Carleton’s addiction to drugs and had tried to persuade her to stop using them. Longfellow also told the court she had asked de Veulle to stop supplying Carleton with drugs, and had told him on the night of Armistice Day that there ‘would be trouble’ if he went on doing so.

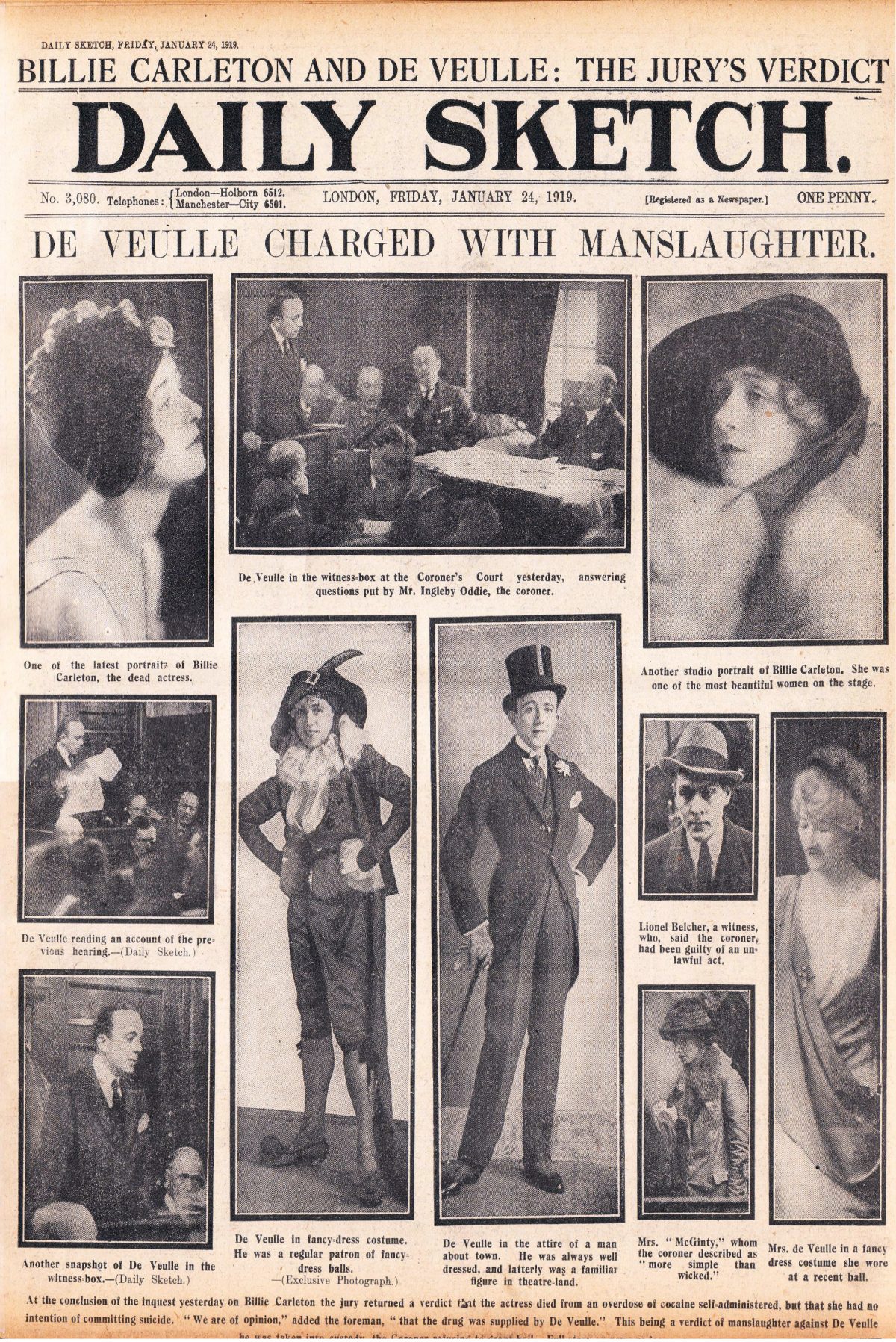

Fay Compton, Billie’s close friend, was also called and told the court that although she knew Billie took drugs and had tried to dissuade her, she had never taken them herself. In the summing up the coroner began, ‘We are approaching the conclusion of this somewhat disgusting case and I am sure we are all very glad to have got to the end of it.’ Evaluating the evidence, it was obvious that he considered de Veulle had supplied the fatal cocaine. Subsequently it took the jury barely fifteen minutes to find that Billie Carleton had died of a cocaine overdose ‘supplied to her by de Veulle in a culpable and negligent manner’, and found him guilty of manslaughter. A very pale de Veulle, after giving his wife a hug, was taken into custody.

Daily Sketch from January 1919

The trial reached the Old Bailey in March where Reggie de Veulle was up against two charges – manslaughter but also conspiracy (with Ada Ping You) to supply cocaine. The prosecutor was sixty-one- year-old Sir Richard Muir, a man described as ‘grim and remorseless’ and famed for his thoroughness and diligence, so much so that when the murderer Dr Crippen learned that he was to face the daunting Muir, he said despairingly, ‘It is most unfortunate that he is against me. I wish it had been anyone else but him. I fear the worst.’

The trial went over the same ground as the inquest, and at the end the judge, Mr Justice Salter, more or less directed the jury to find de Veulle guilty of manslaughter. After just fifty minutes, however, the jury returned with a surprising ‘not guilty’ verdict. For once it seemed Muir had lost a case. De Veulle’s wife Pauline screamed out and collapsed and there was faint applause heard from the public benches. After the weekend, however, de Veulle pleaded guilty to the conspiracy charge and Salter addressed him, saying:

You persistently procured quantities of this drug to satisfy the craving of yourself and another. It is perfectly clear that you well knew you were doing what was wrong. Traffic in this deadly drug is a most pernicious thing. It leads to sordid, depraved, and disgusting practices. There is evidence in this case that following the practice of this habit are disease, depravity, crime, insanity, despair, and death.

Salter sentenced de Veulle to eight months in prison, mitigated, because of his clean record and poor health, in that it came without hard labour. The judge then said, ‘It was a strange thing to reflect that until quite lately these drugs could be bought by all and sundry like so much grocery. I earnestly hope that it may never be the case again.’ During his summing up, Salter had directed the jury that the medical evidence was that Carleton had recently administered to herself a considerable dose of cocaine, and that all the indications were, without being conclusive, consistent with death by cocaine. Mr Huntly Jenkins, for the defence, however, was almost certainly more accurate in his description of how Billie Carleton came to die. He described to the court her tiring day – a matinee in the afternoon, an evening performance, and then the Victory Ball, after which she sat up with Lionel Belcher and Miss Richardson until six in the morning. It was unlikely, Mr Jenkins told the jury, that she would have then taken cocaine and it was more plausible for her to have taken a dose of Veronal (sachets of the drug were in her bedroom, initially taken away by Doctor Stuart who presumably had prescribed them, but brought back when they were noticed missing) to try and sleep.

Almost exactly a year before Carleton’s death, the novelist Ivy Compton Burnett’s younger sisters Stephanie Primrose and Catherine (nicknamed ‘Baby’ and ‘Topsy’), died in a suicide pact, clinging together in the bed they always shared. They had taken Veronal behind the locked door of their bedroom in a flat in St John’s Wood on Christmas Day, 1917. It was almost certain that if Carleton had taken drugs after Belcher and his girlfriend had left her apartment, she would have taken something not to keep her awake, but to help her sleep. If she did, unfortunately she never woke up again, and Marek Kohn, who in his book Dope Girls covers Carleton’s death in exact detail, puts forward the case that the manner of Carleton’s death suggests opiates or barbiturates rather than a stimulant like cocaine, and that she probably entered a deep coma and choked on fluid secretion or even her tongue.

The Carleton case made drugs a long-running concern, not only in the British press but in literature, theatre and cinema. Philip Hoar, in his biography of Noël Coward, lists three plays with drug themes that were performed in the West End the year after Carleton’s death – Dope by Frank Price, Drug Fiends by Owen Jones and The Girl Who Took Drugs (aka Soiled) by Aimée Grattan-Clyndes. In 1923 Agatha Christie, in one of her first short stories that featured Hercule Poirot, wrote The Affair at the Victory Ball in which the Belgian detective and Captain Hastings investigate a society mystery about a young woman who had been found dead of a cocaine overdose. In 1924, Noël Coward, who later wrote in his autobiography that he was ‘pleasant but not intimate friends’ with Carleton, used the tragic death as inspiration for The Vortex, the play that made him famous and which featured a cocaine-taking protagonist.

Lionel Belcher’s promising cinema career was more or less ruined by his involvement in the Carleton affair. His notoriety, however, meant that the movie Yoke, adapted from a 1907 novel that had been suppressed on the grounds of obscenity (a woman has pre-marital sex and doesn’t get punished for it), was re-released, not least because of the subject matter – the story of a young man weaned from drugs by a lover’s dedication. After the court case, Belcher’s wife Gladys, displeased that it was announced in court that he was openly living with Olive Richardson in a flat on Great Portland Street, eventually divorced him. In 1924 Belcher was imprisoned for fourteen days for thrashing his second wife with a cane in the street. The dubious Dr Stuart was fined in 1929 for signing prescriptions for morphine and heroin without entering them in the register (he claimed his actions were due to overwork). As a result his authority to possess or supply raw opium, coca leaves and Indian hemp was withdrawn.

After prison, Reggie de Veulle continued to work as a dress designer in London, and worked with Elspeth Phelps again when she became head designer at Paquin. When Irene Castle came to perform at the Embassy Club for a few weeks in 1923, it was reported that de Veulle designed her dresses, which were described as having very full skirts although the ‘waistlines were all normal because Mrs Castle says the low waistline is not becoming to her’. Subsequently de Veulle moved back to Paris for a few years, but died in Islington in 1956.

Much of this post could not have vaguely been written without Marek Kohn’s Dope Girls which is not only extraordinarily researched but a brilliant read.

This is an excerpt from High Buildings, Low Morals

a book by @robnitm

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.