London summer 1984: I was in love but it wouldn’t last. I was in love with an Iranian woman who was the daughter of a man who had once been two-i-c (or something similarly high-up) to the Shah of Iran. When the Ayatollah seized power in 1979, this girl and her family were spared execution on the agreement that they left the country immediately–with just the clothes that they wore and abandoned all their belongings (house, paintings, assets, toys) to the revolutionary guard. Turned out her old man had been hedging his bets. He was supporting the Shah while at the same time helping the Ayatollah return to Iran. That’s why they were spared. I should have learnt a little something from that.

I’d dropped out of university and was about to fuck up a gig as theatre editor on a magazine covering the Edinburgh Festival. I was in love and that’s why I was in London rather than Edinburgh. And that’s how I fucked up my job. I guess in a way I was unsuccessfully hedging my bets. Though I made good my time in the Big Smoke visiting as many of the turns and groups and what-have-yous that were performing up north that summer–or so I thought. I was seen as AWOL and given the boot.

You live you learn.

But I had also taken time to go and meet and interview people I admired, one of which was the writer Derek Marlowe.

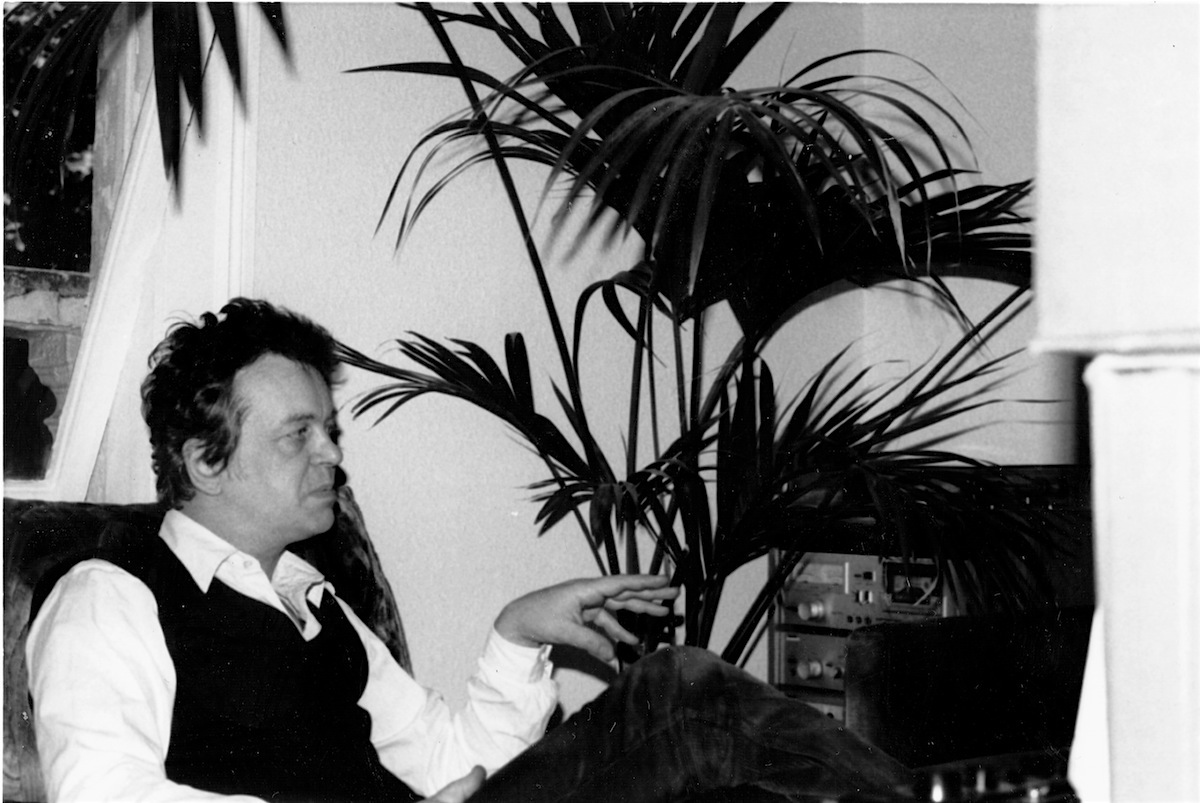

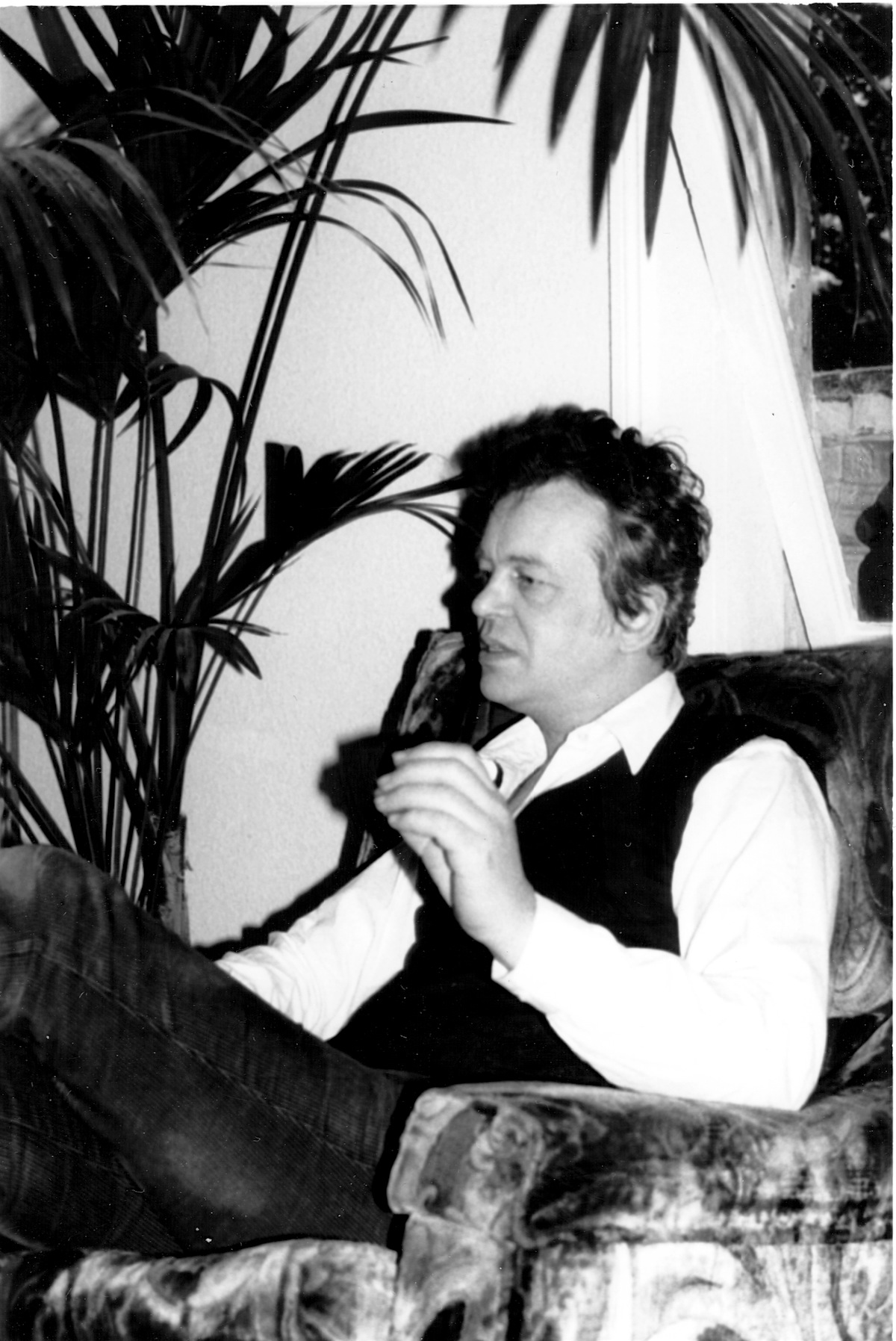

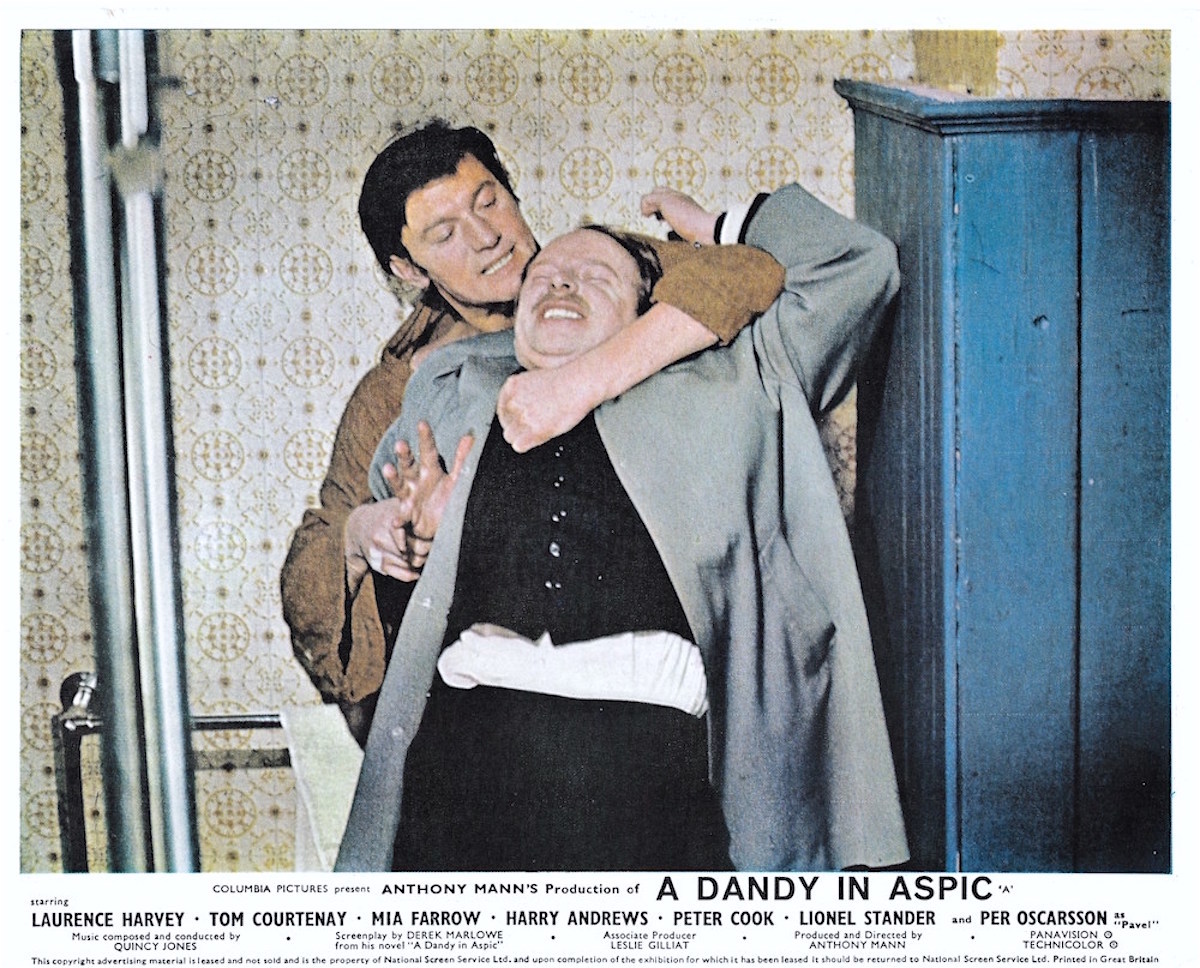

Derek Marlowe avoiding the clutch of a triffid while being interviewed at his apartment in London 15th June 1984.

The author, screenwriter, playwright, and artist, Derek Marlowe was born in London in 1938. His father was a Cockney, his mother Greek. The first hint of his future career came when he was sent down from university for a controversial article in the student magazine.

In 1960, Marlowe was asked to write a play for the Edinburgh Festival called The Seven Who Were Hanged. It was his first big success which earned him a pay check, an agent, a few column inches, while the production transferred to London. Here it won Marlowe the first of his many awards.

He was then asked to adapt Maxim Gorky’s The Lower Depths for the Royal Shakespeare Company in 1962. In 1964 he won a Ford Foundation grant to travel to Berlin, where he wrote two plays and met fellow writers and future housemates Tom Stoppard and Piers Paul Read.

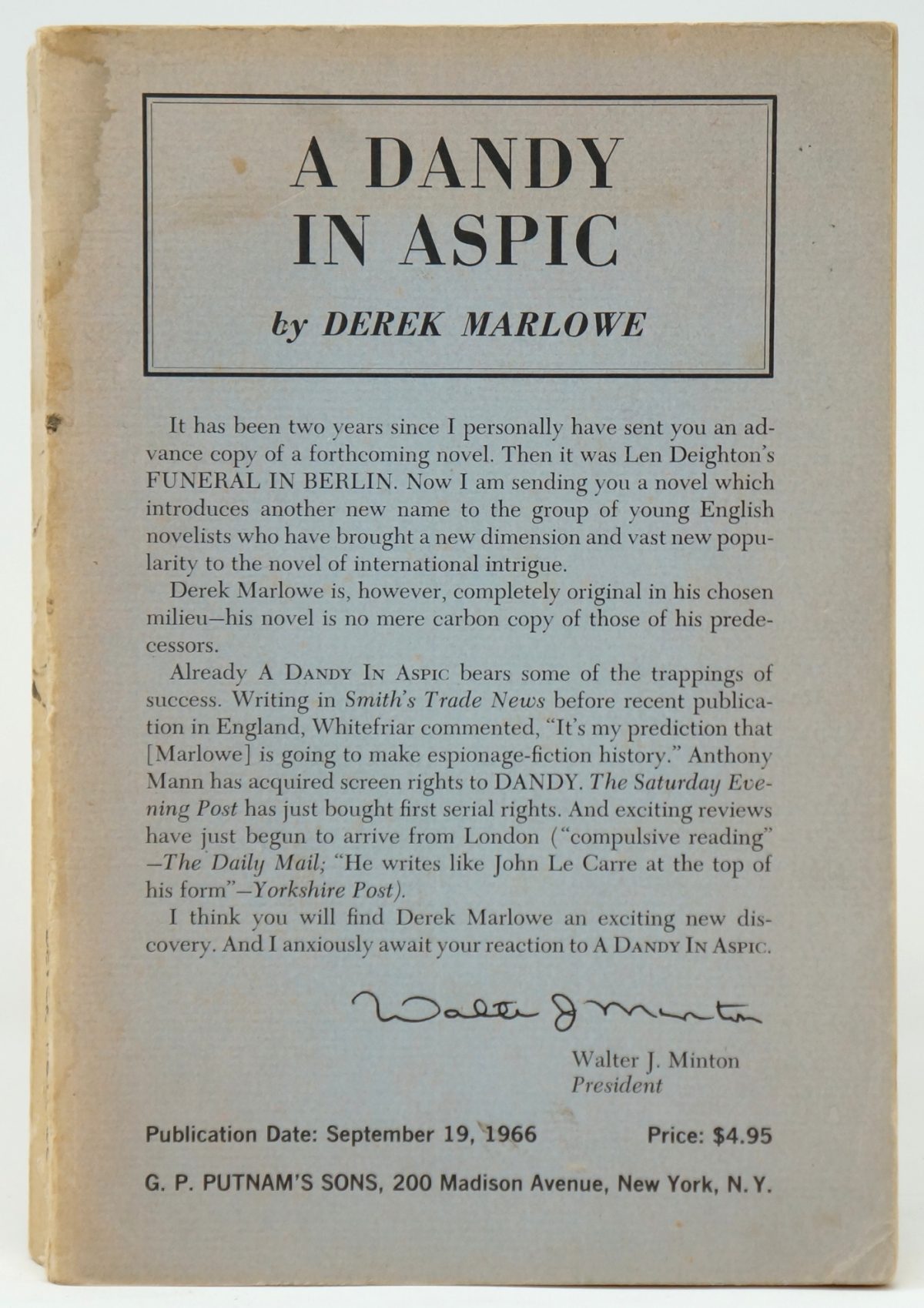

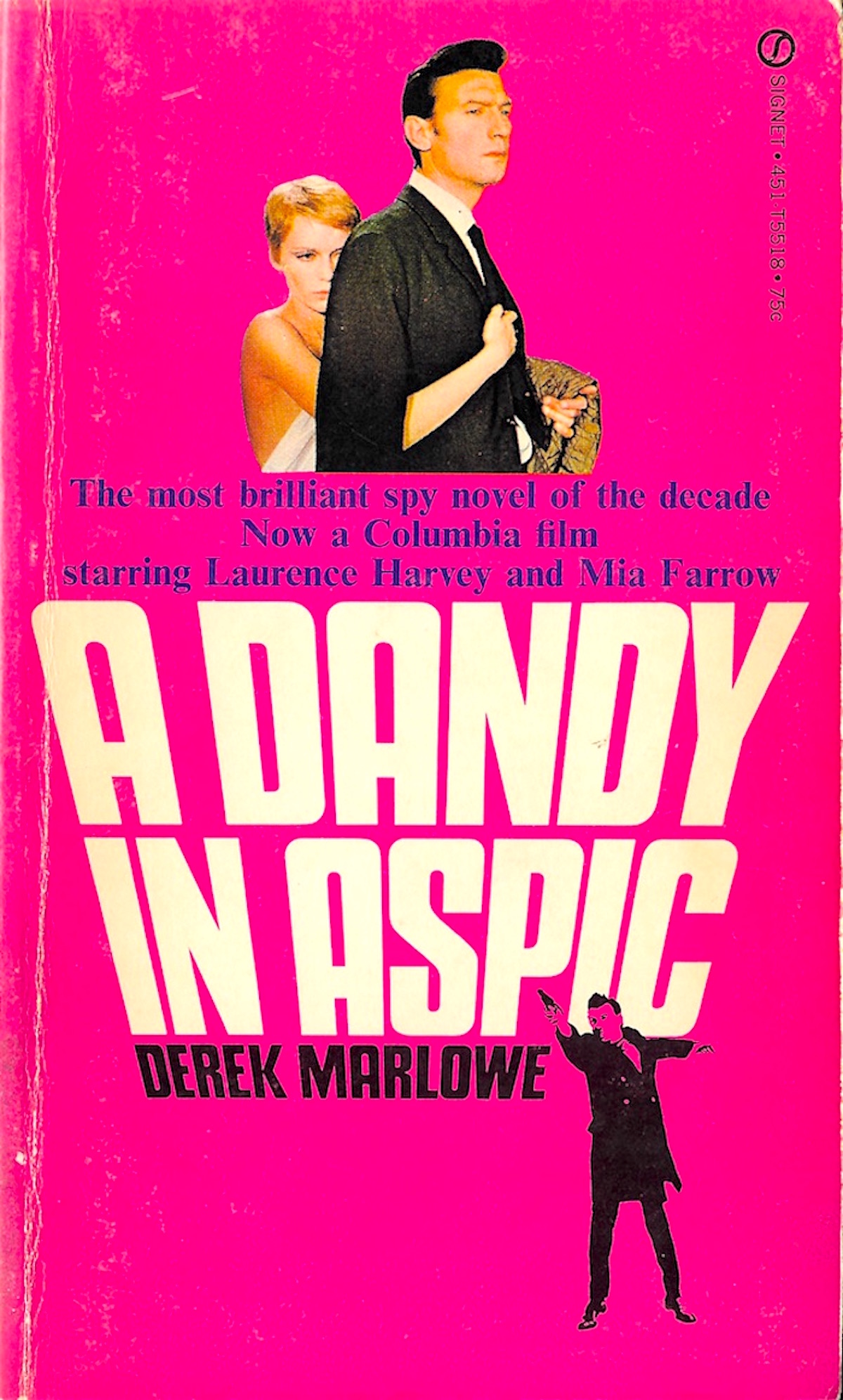

In Berlin, Marlowe began work on his first novel A Dandy in Aspic (1966). This book was an international bestseller and was made into a movie with Laurence Harvey, Tom Courtney, and Mia Farrow.

Marlowe was the hip young writer about town. Painted by Pop artist Pauline Boty, friends with all the right people (including Julie Christie), and co-writing the screenplay for Reflections on Love (1966) with Larry Kramer–the future Oscar-winner with his screenplay for Ken Russell’s Women in Love and author of Faggots and Reports from the Holocaust: The Story of an AIDS Activist.

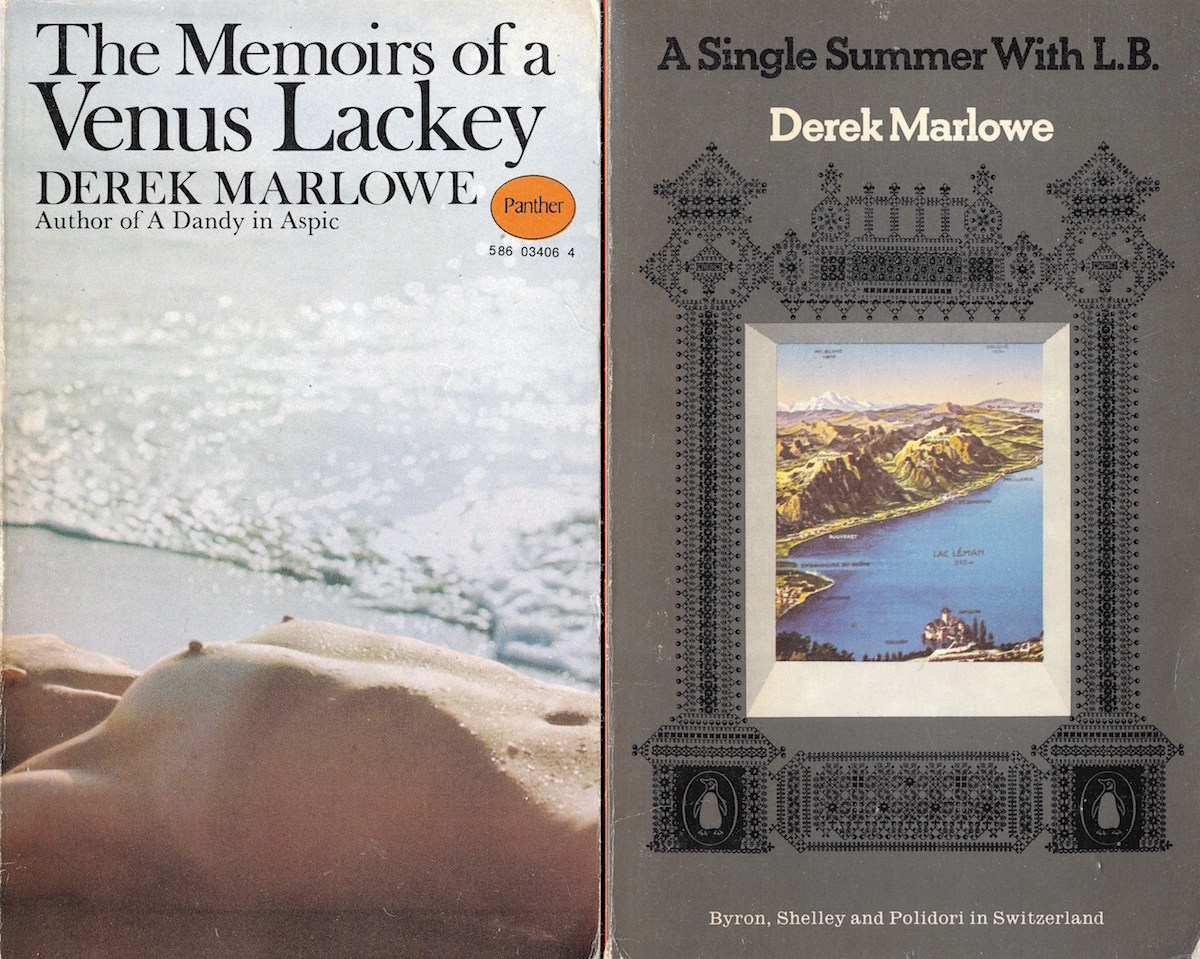

Marlowe’s second novel was expected to be another spy thriller but he opted for a nightmarish gothic psychological tale called The Memoirs of Venus Lackey (1968) which continued with the theme of a man living a double life–but this time asking which one is real? The book was less successful than Dandy.

A Dandy in Aspic by Derek Marlowe. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1966.

First American Edition. Paperback. Advance review copy

This was but a blip, as in 1969, Marlowe wrote a brilliant historical fiction A Single Summer with L.B. retelling that infamous summer Lord Byron spent with Mary Shelley, Percy Bysshe Shelley, and the Doctor John Polidori dreamt up Frankenstein and vampires at the Villa Diodati in 1816.

Over the following decade, Marlowe wrote six more novels:

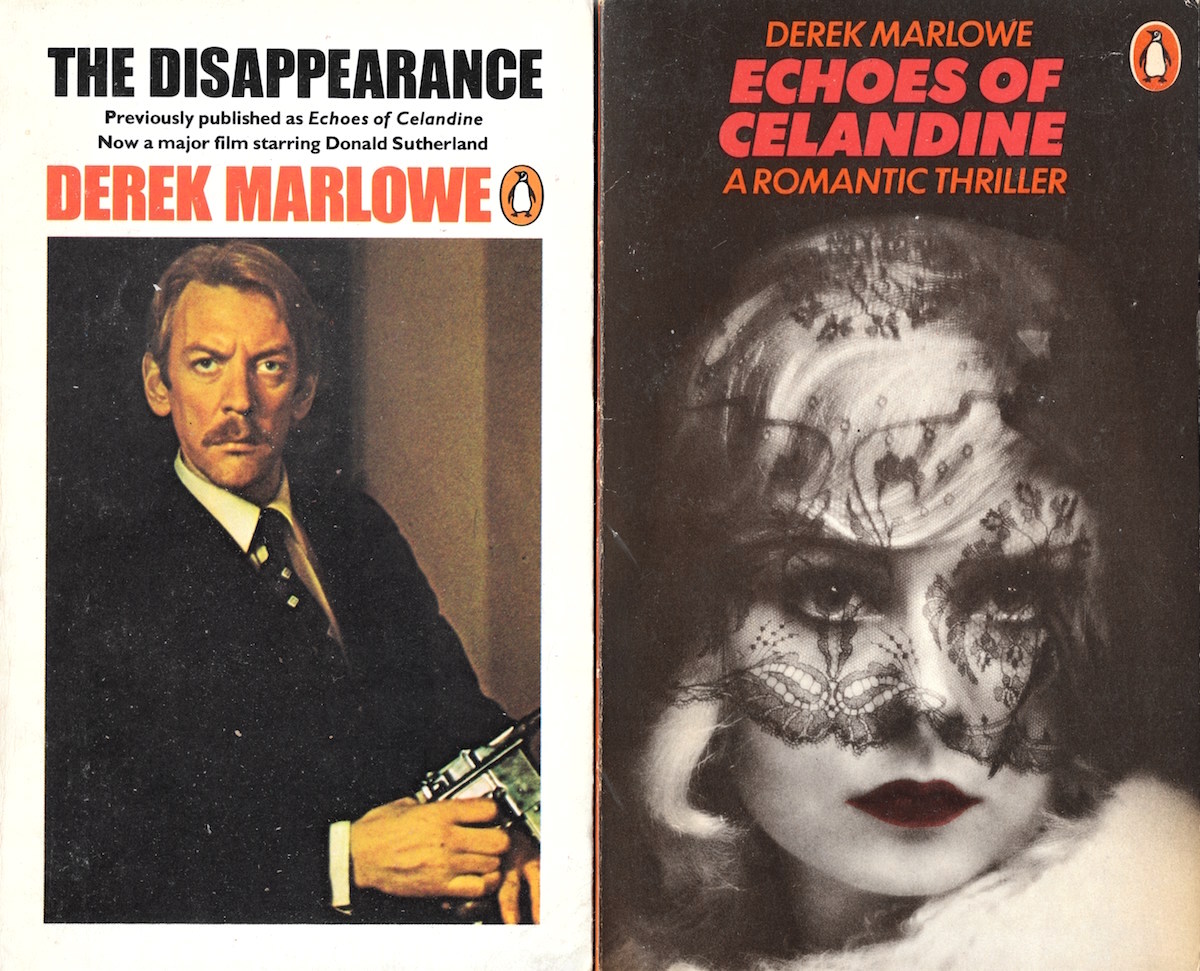

Echoes of Celandine (1970) — the story of assassin, one last contract, and the search for his missing wife.

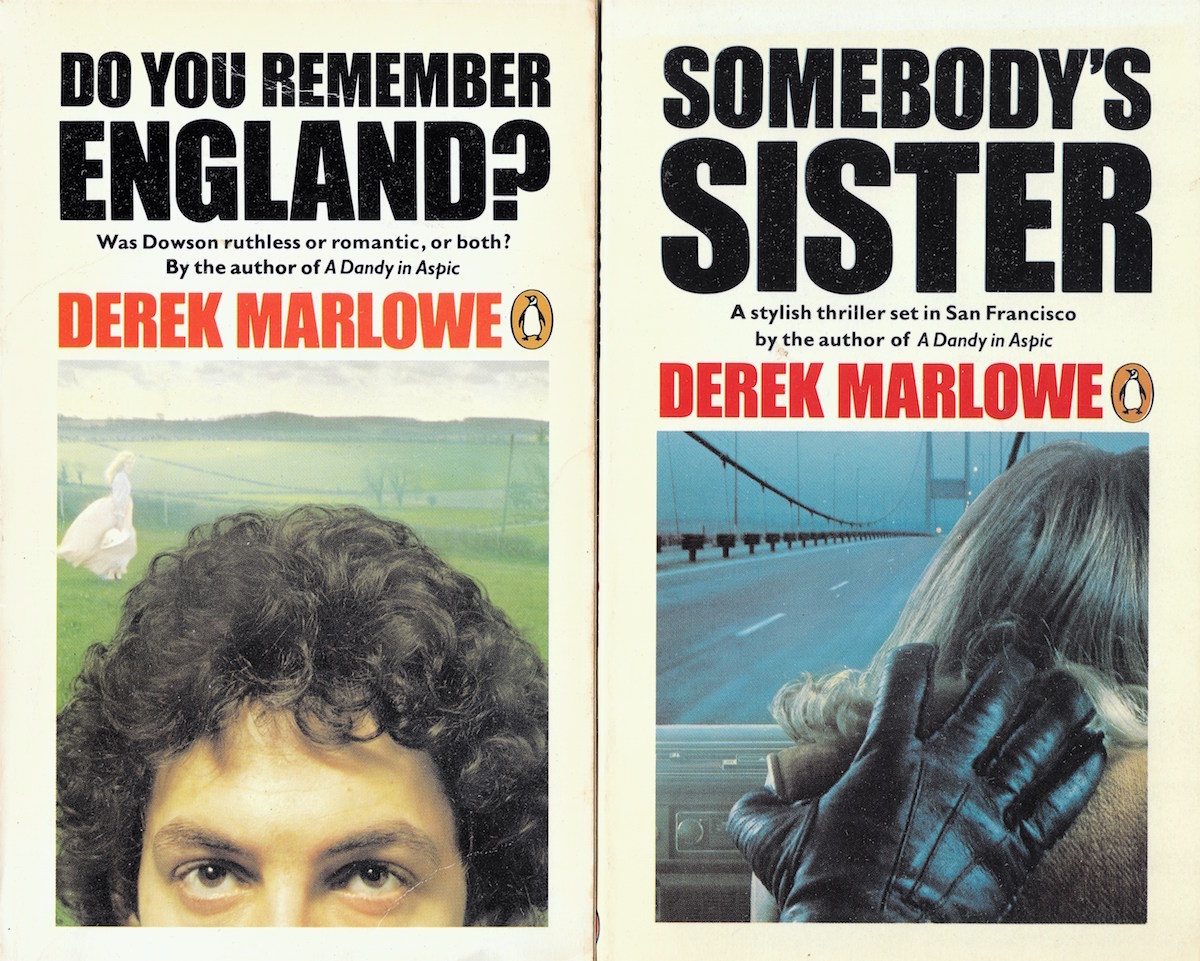

Do You Remember England? (1972) — a mysterious man called Dowson (named after the poet Ernest Dowson–look him up) steals another man’s wife with tragic consequences.

Somebody’s Sister (1974) — a San Francisco p.i. investigates the disturbing murder of a young woman.

Nightshade (1975) — a dark tale of voodoo, sex, possession, and ghosts.

The Rich Boy from Chicago (1980) — the book follows the life and loves a wealthy man who escaped being murdered by Leopold and Loeb, some wags have said it’s Marlowe’s reworking of The Great Gatsby.

Nancy Astor (1982) — a novelisation of Marlowe’s own TV script on the life of the first Member of the British Parliament.

Marlowe also wrote several television and movie scripts including his Emmy-winning screenplay for the series The Search for the Nile (1971), Universal Soldier (1971), A Month in the Country (1976), A Married Man (1983) [from the book by Piers Paul Read and starring Anthony Hopkins], Jamaica Inn (1983) starring Patrick McGoohan. He wrote a draft script for The Spy Who Loved Me and would later write episodes for The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, write an adaptation of Dominick Dunne’s The Two Mrs. Grenvilles (1987) and the acclaimed TV mini-series Jack the Ripper (1988) starring Michael Caine.

I started reading Marlowe when I was in my mid-teens. Picked up a copy of The Disappearance (aka Echoes of Celandine) all because of its cover featuring a moody picture of Donald Sutherland in a suit with a gun. I was smitten from the opening lines as cliche has it and went on to read all of Marlowe’s then published novels.

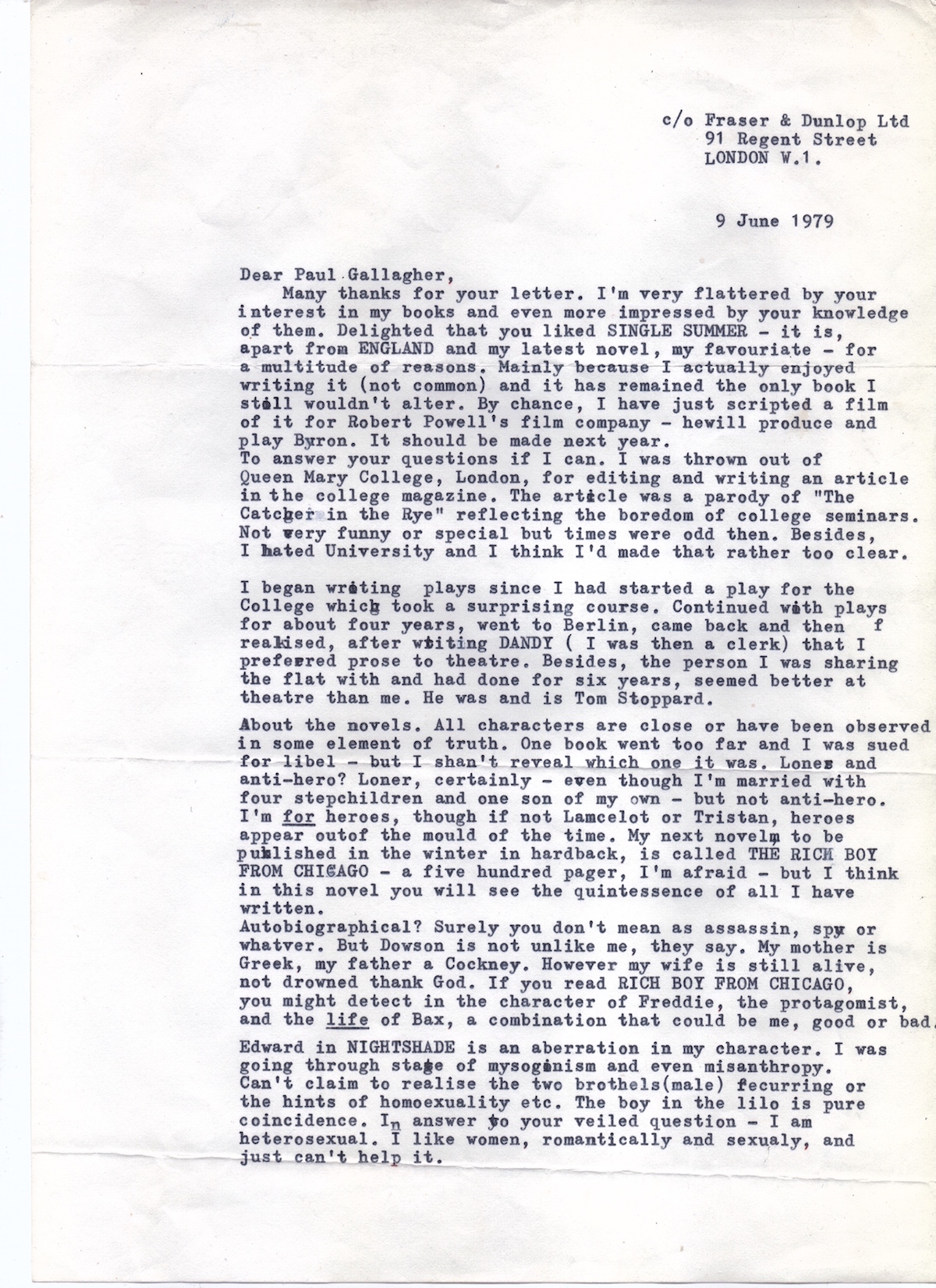

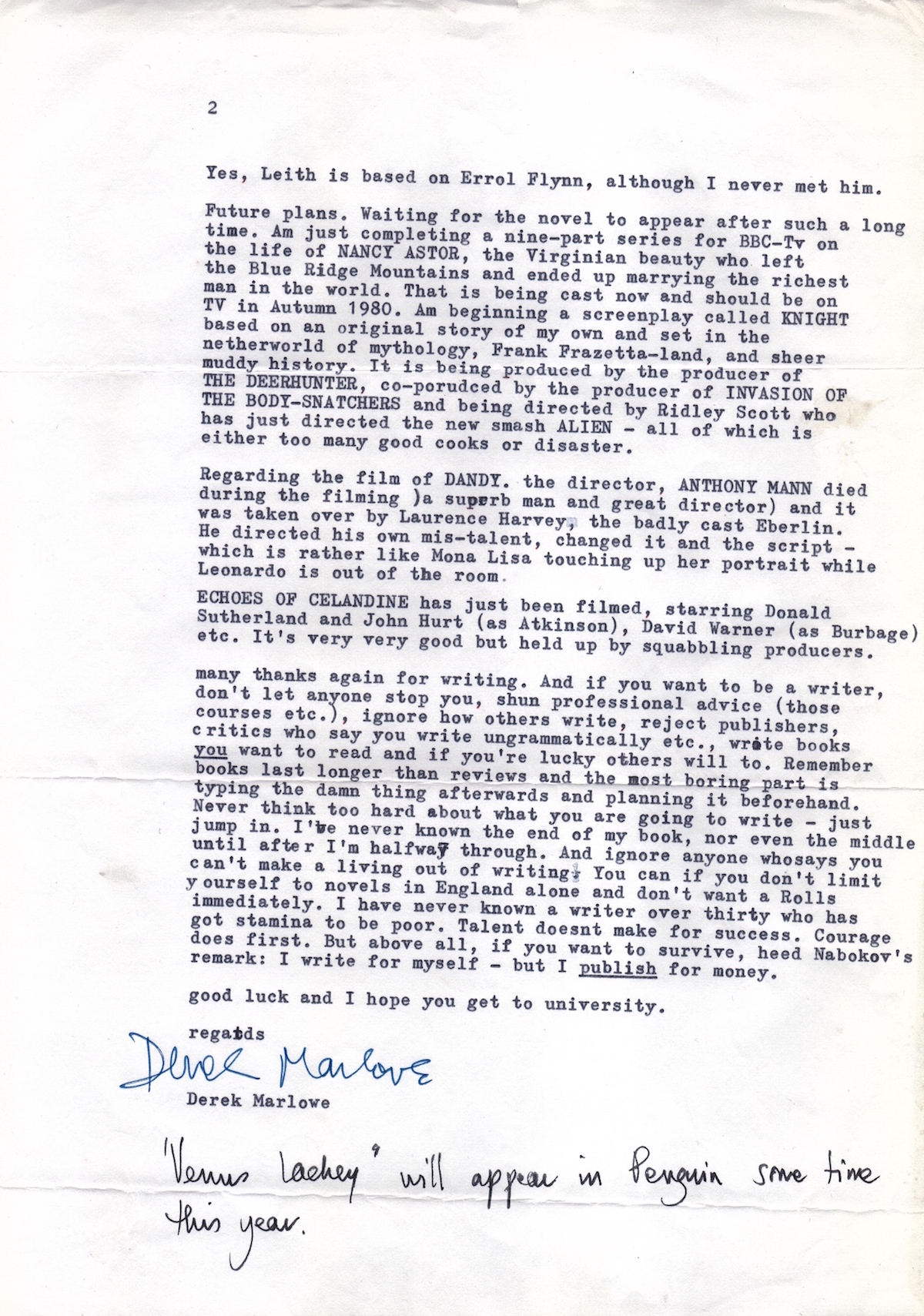

In 1979, I wrote him a fanboy letter asking the kind of irritating questions one expects from an over-earnest research student. He courteously replied and gave advice which fuelled hopes for a better life using words rather than a career of manual labour.

In my dropout summer of ’84, I interviewed Derek Marlowe at his (recently-moved into) first floor apartment. The room had two sofas and an easy-chair pressed together around a knee-high coffee table. The furniture was boxed in by unopened cardboard boxes, unruly monstrous plants all guarded by drunken towers of books teetering precariously across the floor. Marlowe was tall, broad, with large hands and spatulate fingers. He smoked untipped cigarettes, drank whisky and soda and Heineken lager, and had the air of a nostalgic, middle-aged Byron.

The following is a slightly edited transcript of our conversation. I’ve mainly cut down my questions for who the fuck wants to hear me ramble on?

Can you talk about your time at university and why you were sent down?

Derek Marlowe: There was always in those colleges a standard university magazine. Each college tries to produce its own magazine, i.e., to represent the ideas of the college. In fact the college magazine was called The Leopardess, which had all the traditional things of a college magazine, i.e. it has “My holidays,” long speeches which were usually by people talking about, because my college was mainly science, neutrons, and things like that. Very dull. Printed on Xeroxed paper.

Then a poet, called Travers Lee Harwood, who, I think he’s still alive, I’m not quite sure, a wonderful poet, who looked like a Jesus Christ figure, and he was in the English department. I adored him because he was totally rebellious and he wrote this extraordinary, anarchic poetry. This was about 1959. He was very fond of haiku, and Beat poetry, Ferlinghetti and Allen Ginsberg, which were quite new to me, and he wore a James Dean jacket—this was all quite rebellious for university.

He edited it, then he wanted someone to go with him on it. He wanted to change the magazine, and he decided I was a kind of heavy-weight person because he saw that I never turned up at lectures—I always hung around the Drama Society. I used to do caricatures for the broadsheet and for the university itself. I used to do film reviews. I wanted to be a cartoonist. I did caricatures and cartoons of various people in the college—the professors, the students. We got together and we changed the whole magazine, kind of like Mark Boxer did in the early Sixties for [Michael] Heseltine. We made it glossy. We had poems, we had articles, we had photography, we had drawings, and I think it became a very good magazine. It was quite expensive, but it was kind of footed by the idea of enthusiasm. Then it got out of hand, I suppose in a way, because one allowed the horse to have its head.

Eventually, I think we were influenced by American magazines, we became satirical, which is a kind of silly word to use, but we started poking fun (that’s a silly phrase) at university life. Eventually, the powers-that-be at university didn’t like that and in 1960, about three-months before my finals, I was asked to leave, which I didn’t understand very much.

I had written a piece called “Thoughts on a Seminar” which was basically Holden Caulfield, Catcher in the Rye-kind-of-thing, of a boy thinking what’s happening in the seminar, thinking about all sorts of things other than the lecture that’s going on. Very mild. I was sent to see the Dean, and in my naivety, the Dean asked me to leave. I thought that was a question, and I said, ‘Well, could I think about?’ I mean I was in my third year, and he said, ‘No.’

I was terrified because I had to go back and say to my father, ‘I’m not there anymore, I’ve actually been thrown out.’ At London you don’t get sent down, you get thrown out. My father being a typical Cockney said, ‘Damn, bloody university. It’s their fault.’ He blamed the college, it wasn’t my fault, it was the Establishment, the capitalists, the whole thing.

And that was the end of the magazine. The magazine actually survived for two more issues. Lee Harwood was thrown out too. And that was it.

How did you become involved in theatre after being sent down?

DM: Because the college was between Bethnal Green and Stratford, the Theatre Workshop used to come down which was then in its heyday–Joan Littlewood, actors like Tom Bell, Roy Kinnear, Brian Murphy, and writers like the man who wrote The Hostage Brendan Behan. And there was Harry Corbett. Shelagh Delaney, Frank Norman, who all used to come down to the Queen Mary College simply because it had this huge, great theatre there, to rehearse, to put on plays, try them out. I got to know them and eventually when I was thrown out, I went down to Stratford East and said, ‘Could I have a job?’ And they said ‘Yes,’ and gave me a job in the box office, and in the bar as a cellar-boy, where I had to lug great crates of beer up to the bar. And I worked there for two-years, and rather liked the theatre.

How did you start writing plays?

DM: Because I was working in the Drama Society. I was there as leading actor. I wasn’t a very good actor, I got on mainly because I volunteered. Most of the plays were Tennessee Williams, and I seemed to have managed a reasonable Southern accent.

The head of the Drama Society just phoned me up, I was living in Tuffnell Park then, and said, ‘Would you write a play based on The Seven Who Were Hanged? Because we want to take it to the Edinburgh Festival Fringe.’

And I said, ‘When do you want it?’

‘Well, Tuesday or Wednesday would be all right, but Thursday at a pinch.’

I managed to get the thing out by then, it was quite a short story. Then there were phone calls during the weekend saying, ‘By-the-way, Vince has dropped out, but there’s Charlie, and he wants to bring his girlfriend along who plays a flute could you put them in?’ It was one of those kinds of plays where you actually wrote all these various characters.

We took it up to the Fringe in 1960, which was a very good year for the Edinburgh Fringe. It was the year when Beyond the Fringe was started, Dudley Moore and all that. Albert Finney was there. It was a very exciting time. The play was very successful, surprisingly. It was in a church, and I don’t know, I think Ronald Mavor, the son of one the great Scottish playwrights [James] Bridie, was theatre critic for The Scotsman, and he gave it a big review. It got to the agents in London, and got around The Times, I think it was, and after about four nights, this tall, lanky, blonde-haired boy came along and said, ‘I’d like to direct your play, and take it to the Royal Court.’ Which I thought was extraordinary because it was actually just a jumble of fun. This was Corin Redgrave, who was then at Oxford.

So, he took it down and persuaded the Royal Court, who were doing Sunday night plays, which were called then Theatre Without Décor, in other words, they used the set and the lighting of the weekly play and put on the Sunday night play on the bare boards, and you were lucky if you got to move the lighting. It went on at the Royal Court. I got five pounds for it. I got an agent, and I was a professional writer, and that was it.

[Laughs]

It won an award too. So, I suddenly realised I was five pounds better off, and was considered a successful writer.

Was this around the time when you shared a house with Tom Stoppard and Piers Paul Read?

DM: I’d moved to Notting Hill Gate, it was one of those commune kind-of big houses. I was in the ground floor, Tom [Stoppard] was actually downstairs in the basement, and there were about four-five other people. Freddie Jones, the actor, was just above me. Tom was writing then for the BBC World Broadcasting [Service], I think he was writing an Indian Mrs Dale’s Diary. He had just come from Bristol and was writing short stories.

I got to know Tom very well and by chance [we were both on] the Berlin Colloquium, which was a Ford Foundation set-up for sculptors, poets, writers, playwrights, novelists, to spend nine-months in West Berlin, in one of those wonderful houses with everything paid-for. All you needed to have was something you had done professionally.

By co-incidence Tom and myself were both in the same placement, and the third person was Piers-Paul Read, and the fourth was James Saunders, who at that time was very successful, he’d written a play called No Time for Sparrows. He became the kind of father to the three of us. Our job was to write a one-act play which the Ford Foundation would own ostensibly.

Tom wrote a short one-off play called Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, which I don’t think the Ford Foundation ever actually realised it was that. After we left Berlin, Piers, myself and Tom did share a flat together.

But before this you had adapted Maxim Gorky’s book ‘The Lower Depths’ in 1962–how did this come about?

DM: Lower Depths simply came about when I was walking down the Charing Cross Road. I used to collect first editions (I still do actually, to a degree), but I used to love going to old bookshops, and there’s a wonderful bookshop on the Charing Cross Road called Joseph’s on the corner, which I used to inhabit and where in the Sixties you could go in and find a first edition of Jude the Obscure, Tess of the d’Urbevilles, or Raymond Chandler’s Big Sleep, whatever, for very small prices. An actor, who I didn’t know very well, who was in The Seven Who Were Hanged, at the Royal Court, came along and said, ‘Derek, how are you? What are you doing?’

What I remember most about all this is that it was only off-the-cuff. Someone comes along in a bookshop and says, ‘Would you adapt The Lower Depths for the Royal Shakespeare Company,’ which to me seems extraordinary.

At that time, Peter Hall was just starting, the most important kind-of theatrical company in the world, doing extraordinary stuff with wonderful directors and actors and ideas.

Hall had decided to use the Arts Theater to put on five plays as an adjunct to the Royal Shakespeare Company at the Aldwych, and one of them was Lower Depths.

They wanted it adapted in the current, kind-of working class English (basically it’s Liverpool) format. They’d already cast Wilfred Lawson and Freddie Jones (oddly enough) and Nicol Williamson. And he said, ‘Would you adapt it?’ I got £25 for it.

In between, I also was asked to do a musical for the Mermaid Theater which I got through my agent who was then Margaret Ramsay. A pantomime based on a story by Fred Hoyle, who’d written a story “Rockets in Space”, this was 1962, it was called Rockets in Ursa Major. I adapted that for Bernard Miles who met me in his office with a parrot on his shoulder, ‘Would you adapt this?’ Not even knowing all I’d done, literally. He took it for granted that I’d actually deliver something that people would queue up to see. £25 for that too. I was astonished, I thought it was so easy.

What I didn’t like was actually writing plays. I loved being in the actual theatre, not as much as Tom–Tom actually adores going through rehearsals, and he works like a Trojan to go through every rehearsal and worries a great deal.

When we were in a flat in Euston Square Tom worked at night, I worked at day. He always used to work at night, maybe still does, I don’t know. But he used to take eighteen matches from a matchbox, and lay them out on his desk, one-by-one, side-by-side, and he would write eighteen matches that night, i.e. he would smoke eighteen cigarettes, which would be fifteen-minutes a cigarette, and then he would stop. The thing is he would actually set himself to write eighteen-matches. It was quite a lot. Because if you think about it, eighteen cigarettes, even for a chain-smoker you can’t smoke more than one at a time. He would do that. He would work, over-and-over. He is extraordinarily meticulous about everything he would write. I wasn’t. I saw the theatre as being something rather false. I found the stage, the proscenium arch and everything, terribly restricting.

I know, of course, the greatest writer in the world used it to great [success], but I’m not that. I saw the medium which he didn’t have, which was movies and television, and the novel itself, which didn’t exist in Shakespeare’s time.

Suddenly I liked the idea of expanding, I wanted a broader medium for myself, only because I don’t think I was a very good playwright. I did feel as though I wanted people to do the things, which a stage-director or director or an actor couldn’t do. I wanted to kind-of put people into visions, I think more in visual terms rather than literary terms or verbal terms.

While I was in Berlin I wrote a novel which was going to be a play, but I wrote it as a novel and I suddenly enjoyed it. This is wonderful. I wrote it on trains, on the loo, everywhere. I loved writing prose. I thought it was smashing. When the book was actually bought, and published by Victor Gollanz and then became a bestseller in America, then made a movie out of it, I thought, ‘My God, writing is easy, isn’t it?’

I have learned, of course, that I had the luckiest four-years in my life.

DM: When I wrote Dandy in 1964, there was great deal of publicity and articles and books about spies. Not fictional. There were a lot of fictional books that came out like [John] le Carré, The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, The IPCRESS File, and all those. It came out around that time, simply because there was a great deal of information being given to us about [Kim] Philby, Guy Burgess, and [Donald] MacLean. They were then in the news a lot. Especially Philby, because Philby had then defected and became known as being the “Third Man.”

It was a rather fascinating thing because you wanted to know a lot about them. Being in Berlin too and going to East Berlin and seeing Russian soldiers in West Berlin. Going to the Eden Club, a kind-of strip club, or going to a bar and sitting next to a Russian soldier. The Wall had just been built then too. You felt this extraordinary kind-of friction that was going on. All the red tape of going through Check-Point Charlie into the East, all the pressure of military police, people being spied-on, looked-on, talked-on, that you were stopped in the streets all the time by policemen.

In the same sense, the Russians had that too. Because my “hero” if that’s the word, my protagonist in Dandy was a Russian who was a double-agent, who became a man who had to assassinate himself. We talked to Russian soldiers who were being amicable about their kids, and would go to the Black Sea as we would go to Blackpool. They were the same as you or I. I know that sounds naïve to say but it didn’t seem like that.

The Russians were considered then, in the Cold War, as being monstrous: the “Great Bear of Russia” with these heavy, brutish-looking men, caricatures—far more than now, with Reagan and the way that the propaganda in the West is about Russia. In the early-Sixties, the Russian image was far more dramatic. And that was the time of the Cuban Crisis and the Bay of Pigs. You thought the Russians were all great baby-eating figures who were built like blocks of granite and had brains of peas. In fact they weren’t. It was the fact of seeing Russians in West Berlin, young kinds, nineteen-twenty-year-olds, conscripted, and realising they had exactly the same problems, they were totally confused. They weren’t from Moscow, they were from South of Russia; they were from the Caucuses; they were from Sakhalin; they were Georgians; who had no more relationship towards Moscow or what was happening there than we have with what’s possibly happening in Washington. People from Newcastle, have no kind of relationship, no kind of mutual understanding with what’s happening in the Pentagon, or what’s happening in Washington—it’s totally different. These were huge tribes of people. I found that kind-of, because I was young and seeing it then, rather interesting. I wanted to write about a Russian, confused by this kind-of dilemma, this split thing.

‘Dandy’ is a beautifully written book, were you aware of having such a distinctive style of writing? If so, how did this come about?

DM: I’m not sure. I don’t think I was aware of that. I mean, I know people who have actually, well so many reviewers have said of influences I have had, I don’t think, I mean people said I was influenced by Joseph Conrad in one book. I never read Conrad until the last five-years. I don’t know. I like to think that I didn’t have a style. Certainly when I was writing Dandy in Aspic, I wasn’t aware of even actually creating a style. I wrote the book simply because of the way I wanted to tell the story. I found it was the best way to tell the story about those events that happened. I was never actually aware that I was writing any particular style, until perhaps later.

There are writers that I like, obviously, you are influenced as much as you are influenced in life about things, something influences you, whether consciously or not.

I know that I read a lot. I mean, one thing I was lucky about, is that my parents gave me lots of books. I was very ill when I was young, from about the age of eight till eleven. I was confined to bed for four-or-five weeks every Easter with a lung problem.

I was given endless comics, there was no TV then, no radio then, so I used to read books. I was reading Tom Sawyer and Dickens, when I was about seven-years-old, eight-years-old, given to me by aunts. I read a lot of books and obviously that reading must have burned at my mind. I think in my second novel [Memoirs of a Venus Lackey], yes, I was influenced probably. Now when I read it, I think ‘Oh, my God. Derek you’ve been reading Nabokov.’

Certainly, I can see that certain writers have got a great influence because their style is so persuasive. It’s like hearing music.

Now, I don’t like Nabokov very much, but I loved Nabokov at that time, and I loved Graham Greene very much, but I’ve always liked very simple styles. I’ve always liked being romantic, possibly over romantic. I’m now trying to write with less adjectives–If that’s being less romantic.

Can you talk about the film version of ‘A Dandy in Aspic’ directed by Anthony Mann, and starring Laurence Harvey and Mia Farrow?

DM: Anthony Mann was a man I admired very much. He was the last of the great American film directors of the forties. He was in the same field as John Ford and Howard Hawks but making Westerns. He didn’t care much for words–it was movies. He was brought-up on movies. Yet he was a very intelligent man. He worked for the Group Theatre in the thirties. I think, when he was dying, when he made A Dandy in Aspic, he had married a young ballet dancer, his sixth wife, and, basically, he wanted to make a film that was set in England.

The book was given to him, it was a bestseller, he liked the idea of doing something modern, he hadn’t done that for a long time.

I was rather lucky, he just asked me to write the screenplay. I’d never written a screenplay before. He said, ‘But you’d never written a novel before. You wrote Dandy.’ I used to visit him in a London clinic, and he basically wrote the screenplay for me. He gave me credit for it. But it was basically him saying, ‘Do this, do that.’

Laurence Harvey wasn’t right for the part. He knew that he wasn’t really a dandy. He played it as if he was a thug in the early ‘50s. He was quite a good actor but he wasn’t this kind of actor. He’s an actor who’s all right playing a lot of seedy B-movie kind-of spivs. He’d never get away from that image. But he was very on the movie, because he was married to Joan Perry, who [had been] the wife of the head of Columbia Pictures, who financed the movie. So, he had a lot of power.

When Anthony Mann died, Laurence Harvey phoned up Columbia Pictures and actually took over the movie. He was quite a ruthless man. There were scenes, which I saw, which had been shot by Anthony Mann with actors like Per Oscarsson and Tom Courtney, very good actors, Peter Cook, Lionel Stander. And Mann knowing, like a very experienced director, he knew that one thing that Harvey can’t do is close-ups. He was very good at kind-of back shots, doing it moving, but close-ups there’s a kind of posing, wooden face, so he never did close-ups of Laurence Harvey.

DM: What I was surprised about when I saw the movie, I suddenly saw horrendous close-ups of Laurence Harvey. When he took over the film, he went to Austria, or Shepperton, or Pinewood, or wherever they needed to go, and shot close-ups of himself and inserted them in all these scenes and the lighting’s wrong, the whole thing’s in chaos.

The film could have collapsed on its feet, but Harvey did save it, because when a director dies, with a lot of money invested in it, it’s just canceled out. He did save it by making the film and finishing it off, and getting it out. I respect him for that professionalism. But I think he didn’t make a good job of it.

How did you feel about having such incredible success so early on?

DM: I felt wonderful. I was arrogant, cocky, absolutely, appallingly. I was whipped around America by Putnams, who published the book in America. Don’t forget this was ’65-’66, this was the time of The Beatles, of Julie Christie, of Swinging London, of Time magazine going crazy over this small city we’re in now.

I was then, what twenty-five? twenty-six? I had a Beatle haircut, I always had long hair, I was the most obnoxious person ever, but adorable. I loved it. It was terrific. To actually come from nothing, to have no money, I mean it seems like a cliché but basically to have no money, to be living on benefits at the same time Piers-Paul Read basically had…I remember once, we were watching Top of the Pops, I’m talking about Tom Stoppard, myself, and Piers-Paul Read watching Top of the Pops, and Mick Jagger was singing Satisfaction, who had always been Tom Stoppard’s great idol—Mick Jagger. It was like you realised this was the great star image, forget The Beatles– The Rolling Stones. Satisfaction, Brian Jones, and this wonderful guitar intro. And they were going to be millionaires. And we talked about who was going to get the first million dollars. We all thought Tom would be it, the first person, not a question of top dog, but big money, i.e. more than half-a-crown. But it was myself with Dandy merely by a whisker, because Tom got it with Rosencrantz and Guildentsern, and Piers with Alive a bit later.

To me it was extraordinary. I adored it. I remember sitting in a bar in New York, and Walter Minton, who was the head of Putnam’s, said, ‘Derek, what’s your next spy novel going to be called?’ Because there were two-versions of Dandy in Aspic, there’s an English version where I killed Eberlin, the protagonist, off. In America, I was ordered to keep him alive. The Saturday Evening Post serialised it, and they wanted him kept alive. I thought it had been a cop-out to kill him anyway, it wasn’t really solving the problem. But Putnam’s had thought of a sequel, and I said, ‘Oh, I don’t know about spies, I don’t know much about spies, I want to write a love story.’ And he said, ‘You’re joking. You’re not going to write a love story?’ And I said, ‘Well, not a love story, I have this idea…’ And he listened to this idea, and I could see his face collapsing and thinking, ‘My God, what have I got here? I’ve got another one of these English people who want to come over here and write cultural books!’ And he refused to publish my second book. He said, ‘I don’t think any publisher will publish this.’ Luckily Viking did, and that was it.

DM: When I came back from Dandy in America, and the book was successful and I also had the money, and I also got married. I met somebody I wanted to marry, who was married herself, and she had four children, and we eventually did get married. So, the whole of my ambition was to get married. The money was used to buy a house and to look after four stepchildren, which to me was much more important. And simply because I found writing quite easy, it seemed to me. I could sit down and write a book, and there it is. Of course, it’s never happened since.

I still think Dandy is a very good book. The last time I read it, three years ago, I did have that thing that Scott Fitzgerald said, ‘Baby, you had a nice talent there.’ It was nice to know it was there. It was a nice surprise to find the book was not as bad as I thought it was. But I got involved with my private life. I wanted to write a novel, and I chose a book that basically I enjoyed writing, because I could afford to.

I wrote Venus Lackey and I wrote a book about Byron [A Single Summer With L.B.]. Then I wrote a book called Do You Remember England? and that was about a year after I got married, which was based on my marriage, and also my relationship. My own private life was affecting the way I was writing.

I think A Single Summer With L.B. and Do You Remember England are probably the books I still like best. They are always the books that people ask me about. It’s extraordinary those books have lasted, much more than anything else. I think Dandy will [last], simply because it’s a spy story of its time.

After that I started thinking about writing books to make money, or to write screenplays, or to write television to make money. I started thinking more about, as I do now, that I am a professional writer I’ve got to pay my taxes, I’ve got to obey my client. I’ve got to earn money. I am much more conscious since about that. But for four books in a row, I didn’t think about it at all.

What inspired your second novel ‘The Memoirs of a Venus Lackey’?

DM: It was a dream, I think. It began as a dream, but also the idea of teasing the reader. I just liked the idea of writing about somebody who’s actually lying to you. It’s a first person novel and you’re not quite sure if you believe him or not. I liked the idea of the thriller though. I think basically all my books have been thrillers, in a sense, except for the Byron book. Even Do You Remember England? has an element of “what will happen next?”

Venus Lackey was a fun book. To be honest, I don’t know why I wrote it, why I chose that idea, how it came about, too much. I know that I got very excited about writing it. I know I wrote it very fast. I mean, literally three-weeks, three-and-a-half-weeks. Dandy was written in four. I used to write very fast. I wrote a lot, a lot of television scripts, almost all submitted in haste and rejected in leisure, and I’d given up writing stage plays. I was almost solely concentrating on novels. I have no idea why.

‘Venus Lackey’ is such a different book from ‘Dandy’ but there is a similarity in the split of the central character’s personality. What was the response to ‘Venus’?

DM: I can give you an answer to that and criticism in general. I’ve never actually had a very large critical, favourably critical press. Oddly enough, there are critics who reviewed two books of mine, which are thrillers, Somebody’s Sister and Echoes of Celandine, i.e. The Disappearance, who said, ‘I’ve always liked Derek Marlowe’s sense.’ But I’ve got reviews of Dandy in Aspic by them and they didn’t like Dandy in Aspic at all. In fact Dandy in Aspic in England got very bad reviews—not bad reviews, but under that kind-of terrible thing where any thriller is put under “Crime Writer” so you’ve got one paragraph, whether you’re Elmore Leonard or Ed McBain, or Raymond Chandler or whoever it may be. Even in those days John Le Carre and Len Deighton, they were put in a small pocket and there would be five-columns to a Bloomsbury book.

I never got much press on Dandy in America. I did, lots-and-lots of press, but I’ve never had very good reviews or even large coverage. In fact, Rich Boy From Chicago got about two or three reviews at the most. I am usually very under-reviewed. I suppose all writers say that, but I am under-reviewed. My biggest audience is in America, where I am reviewed quite as much, I think, as I expect to be as an English writer writing.

In fact, most of my non-book work comes because of my reputation in America as a novelist, i.e. from movies or from television, and most of my successful things, like money and awards come from America. Even though I really haven’t lived there. I don’t know why. I think the books like Single Summer With L.B. is a very English book—it’s a personal but factual study of Byron, a nice dilettantish book about Byron in Switzerland for a year. Do You Remember England? is a very English book. I think that perhaps Nightshade is an English book, but, yes, they are acceptable in America. The reviews have been from America. If I have had reviews here they’ve been from the weekly magazines The Spectator or The Listener, New Statesman. Sometimes, it can be very depressing.

I was with Cape for a long time, who I liked very much as a publishing house, but didn’t very much like the person who I was working with there and that’s why I left. But basically, I’d love to get much more attention here.

I don’t think I am any different than any other writer. I haven’t written a novel for five-years and haven’t had a novel published apart from Nancy Astor, which was a mistake in my part as I was contracted to write the TV-version of the novel—I didn’t have to, I could have refused it, but basically I was obliged to. I don’t consider Nancy Astor as a book of mine. I think it is a very bad book. I think I did it very badly, and I feel rather guilty that I was paid to do it.

Other than that, yes, of course but the turn-over of books in England and America, any kind of country, one is how many books can a bookshop have? Penguin, unless you’re part of the classics, of which I’m not, I don’t expect any kind of paperback house to have all of your books in print all the time. They are in the libraries, so people can read them.

What the response from the public like?

DM: Quite, quite good, surprisingly. I mean, I get letters, a lot of letters in fact, more than I think. Mostly from abroad, New Zealand, Australia, Africa, America, usually asking ‘Whys?’ about why I wrote this, or people have actually read and see connections. I mean, I had one letter about four months ago which is not unusual, this kind of theme that I’m talking about, I mean, it’s appeared quite a few times in either letters or articles—why do I have so many suicides in my books? I was never aware of that, and now I am aware, terribly self-conscious that a lot of people in my books commit suicide, in some form or the other. But I am always very flattered not only that they read the book that they actually sat down and wrote to me.

I remember the book everybody in the fifties seemed to have read which was Catcher in the Rye. Holden Caulfield said I wished I could have phoned-up Scott-Fitzgerald and said how much I preferred Gatsby. I do feel that people have this wonderful assumption actually that the easiest person to write to is a writer, because his address is on the book jacket. I mean, there it is. Penguin Books, Harmondsworth, Middlesex, or Weidenfeld, whatever. Or you can write to the writer, quite simply, because you know his address. It’s always going to be forwarded on to the writer. I think it’s wonderful in fact, that someone has taken the trouble to buy a stamp at the post office, go in, post it. I find that terribly flattering, you know, and very, very, always very touching. It’s wonderful that people should write to you and I always write back whatever they ask. I wrote back to you, I mean you wrote to me. I thought that had extraordinary charm.

Derek Marlowe’s reply to my fan mail, June 1979.

DM: When I went with my first agent, Margaret Ramsay, I’m not with her now, simply because she is a play agent and I don’t write plays—maybe one day I will, I’ve got a feeling I’d like to write another play. But when I first went to Peggy Ramsay, when I’d written The Seven Who Were Hanged and Lower Depths, I didn’t have a typewriter because I couldn’t afford it. Peggy said, ‘Here’s a typewriter that you can have.’ It belonged to Emlyn Williams, and Emlyn was one of her client’s—he wrote The Corn Is Green on this typewriter, and he’d left it in her agency and said, ‘It’s for a writer who needs a typewriter. The only proviso is that when that writer has written something successful, he will give the typewriter he’s written something successful on back to the agency for the next one.’ Which I did.

I gave the typewriter I wrote A Dandy In Aspic on to another writer friend.

What about ‘A Single Summer with L.B.’?

DM: That came about quite simply as I was asked by Tony Richardson to write a screenplay of Laughter in the Dark. In fact, I suggested to Tony Richardson, about two months before this particular event, he’d asked me, at that time there was a company called Woodfall Films, where Tony Richardson was one of the directors of it, and asked me what books I’d like to write the screenplay, and I suggested Laughter in the Dark. And then about two or three months later, Tony phoned me up and said, ‘Would you adapt Nabokov’s Laughter in the Dark?’ So, I did. I adapted it. At that time, Richard Burton was going to play the middle-aged lover of the young girl. Marianne Faithfull, I think, was cast as a seventeen-year-old. Basically, it was a Lolita-complex story–an old man in love with a seventeen-year-old cinema usherette. Marvellous kind of story but, unless you have this age-gap, i.e. a middle-aged man and a young girl, the story means nothing.

Then I went to America to do promotion on A Venus Lackey and came back to find out that the film had been re-cast. Richard Burton had walked-out, and Edward Bond had written the screenplay. I liked the screenplay I wrote, and I knew Burton liked it, and he had walked-out, for reasons I don’t know, but anyway, suddenly I had been thrown aside and a new screenplay had been written by Edward Bond. I never saw the film and I don’t know if Edward Bond’s was worse or better, but obviously, it was approved by Tony Richardson. The thing is, they’d cast Nicol Williamson and Anna Karina who were the same age.

This kind of normal, naïve disillusionment made me curl back and it was my wife that said, ‘Why not go off and write that novel you want to write about Polidori?’ who was Byron’s doctor in 1816, and who committed suicide at twenty-two-years-old, and why he spent six-months, nine-months with Byron, came back and killed himself. And so I did. Simply as a panacea for a sore ego.

I went off with a friend of mine, we toured all the areas that Byron went to and I came back with a book.

What did you think about ‘The Disappearance‘, the film version of ‘Echoes of Celandine’ which starred Donald Sutherland?

DM: After Dandy in Aspic, and seeing what had happened to it, and also realising I didn’t like writing the screenplay of Dandy in Aspic, it was always going to be a failure to me to write the screenplay. It would have been much easier if some other writer had come along to the book and taken it away and torn it apart and told their version of my novel as a movie. Me doing it myself, at that time, I was terribly scared and in awe of people like Anthony Mann and Laurence Harvey and Mia Farrow.

When Echoes of Celandine was bought, I was approached indirectly to write the screenplay, I said, ‘No.’ Paul Mayersberg wrote the screenplay. Paul did his version of the screenplay, the way he saw it. In fact, the screenplay he did was probably the fourth version and a lot of things came in, as anybody that’s written for the movies will know, that the final screenplay often has so many kind-of compromises and cul-de-sacs that have gone on before they’ve actually got there.

I think the biggest fault to my mind was I wish that he had kept the ending as the book because I don’t think the film works. I think that Stuart Cooper made a marvellous job of directing it and I think the casting was great, except Donald Sutherland, who I thought was very unsympathetic. I think the hero should have been very sympathetic. Sutherland is not a sympathetic actor on the screen, to me anyway. He always appears to be too laid-back and little bit above, superior to me and the audience, and sometimes in his own world, and a little bit cold towards his fellow human beings, and certainly in this film he did. I think that the attraction for the hero in the book is that he’s weak, he’s soft, he’s in love with his wife. To actually see a man who’s so committed to being an assassin and at the same time wants more than anyone to find out where his wife is, in the end the professional side of him takes over and he kills his wife. The very thing that he wanted to save. That’s what the story’s all about.

How much of ‘Do You Remember England?’ is autobiographical or at least filtered through the prism of your life?

DM: I think in hindsight that book [Do You Remember England?] is probably the most autobiographical, but I don’t I think I am [the central character] Dowson—maybe only in the sense that the story’s about a man who marries a married woman, or pursues a woman who’s married, who’s got children, as I did then. I do have a Greek mother and I do have an English father. I did wander around Europe a lot. There are parts of Dowson I don’t like very much. He’s not a very sympathetic person. He’s very cold towards Emily…rather louche, cool, and somewhat cold, and then rather sadistic.

I hope I am not like that. Everybody says that you are aware that you are writing about what you know. The emotions that are very strong that you experience are very personal emotions. When you try to relate them, whether they are love, hate, fear, whatever they may be, somehow the easiest way of putting them across is to relate very closely to how you felt that emotion in the circumstances. It’s the best way sometimes.

But my wife’s still alive—she didn’t jump in the river.

There are certain thematic similarities in your novels but they cover such a diverse range of genres–spy story, fantasy, historical, thriller, horror–and to an extent the characters are different…

DM: I don’t think actually they are very different. I think most of my characters are loners.

I think they’re written for different reasons. As I told you, Single Summer was written for a kind of feeling of pique about this man who wanted to go away into Europe. Do You Remember? was written because I wanted to put down the feelings of getting married—the affair that I had. Somebody’s Sister was really written for the most simplest of reasons: I love thrillers, I love reading thrillers very much. I’m a junkie for thrillers, but good, mostly American thrillers.

I don’t like English thriller writers, I don’t like P. D. James. I find their style quite appalling except for Colin Dexter and a couple of other people I like very much. I never liked Dorothy L. Sayers. I do like getting from A-to-B on a plane, or lying on a beach, having a thriller—Ed McBain, Elmore Leonard, Raymond Chandler, which are good old Americans. Ross MacDonald, all these people. I’d read them all. And I thought, ‘Jesus Christ, I must write a book for somebody like me who wants a thriller to go from London-to-San Francisco.’ So I wrote Somebody’s Sister when I got to San Francisco. I was there basically on holiday, working holiday, I was writing a screenplay plus doing research.

Herb Caen, who’s a one of the top journalists in San Francisco, who writes a column, invited me to go around the San Francisco Police Department, with the idea of writing a thriller, and the idea of writing something I’d like to enjoy to read. We were driving down, past Union Square, I was in the back of a squad car, and there was the wah-wah-wah on the radio, whatever, you know, ‘be vigilant,’ and code. I got to know the two drivers. One of their jokes was to take me on a Sunday morning and take me to the morgue, knowing that I’d have a hangover.

Anyway, they were talking about some girl who’d been killed and it had been a running story, basically that this girl had been found dead. She’s in the morgue. I said, ‘By-the-way, what happened to this girl?’

They said, ‘What girl?’

‘The one that was found.’

‘She’s still in the morgue.’

And I said, ‘Well, what’s going to happen to her?’

‘Oh, who cares, she’s just somebody’s sister.’

That was the title.

Since I’m not American, I put someone who’s almost American which was Brackett and that was the story. That took a year to write. I wrote that in Gloucestershire, thinking it would be easy. It took me a year to write that book. It’s the longest time I’ve ever written. I worried more about that book than any other. Books are simple now, but then it took me a year. I wrote something in between, it was a script, but it took me a year to write the book.

How do you go about writing? Do you have an idea to start with? Or, do you have, as say John Irving has claimed, an idea of the end which you work towards?

DM: I never know how. No, I don’t know the end either, I know only..

Basically, I usually get conscribed by the character and a scene. The landscape. I write the landscape first, then I put a figure in it. Rich Boy From Chicago began [because] I knew vaguely that I wanted to write about a chronology of someone who was very different from me but covered a period of time which was the years before the last war up to the Sixties.

I didn’t want to be identified with the character, so I chose someone who was totally different from me. He was American, rich and Jewish. I was not, or I am not any of those. I didn’t know how to start it. I didn’t know where to begin. I had a chronology given to me, a chronology of history, dates and what happened in each, and automatically when you’re get something like that you look your own birthday. So, I looked-up twenty-first of May, which was the date I was born, and on the twenty-first May, 1924, in Chicago, Illinois, Leopold and Loeb murdered Bobby Franks, The “Thrill Killers,” by chance they were going to murder someone else.

I got a book about Leopold and Loeb and I found that in fact they circled Chicago, the suave, rich part of Chicago, looking for a particular boy with their plan to murder. They knew the rich, Jewish boys who went to this particular school which was the Harvard Preparatory School in Chicago. They stopped somebody, and by chance the chauffeur turned up. So, in the end, they murdered somebody else, Bobby Franks. I thought, that’s where it begins.

I began the book with Leopold and Loeb wandering round. The idea of The Rich Boy From Chicago beginning his life by a freak—he could have well been killed. That’s how it came, simply by looking at my birthday, finding Leopold and Loeb and the story went from there.

Almost sounds like you believe in fate?

DM: I don’t believe in fate in the sense that one sits down and fate will take over. If you press a button and your car will drive itself. No. I do think, in fact, that fate has a lot to say in anybody’s life, but only if you look back on it.

I know a lot of things that I’ve done, not only as a writer, but also personally, opportunities that I’ve seen, or things thrust upon me that I’ve taken advantage of or in fact, I haven’t taken advantage of, but turned out badly, or well. The way my life, or your life, I don’t think that’s anything new. I think my characters are often influenced by fate I find because I don’t know where my characters are going to go. I write and I’m much more interested in Brackett or Eva or Freddie, or whatever he’s called, I wake-up in the morning and I’m so turned on by these characters and I want to know what they’ll do next. And after a while they decide for me. In fact, I suppose it happens that for most of them fate has decided what happens in their lives. Dowson in Do You Remember England?–because of the death of the Errol Flynn character that he meets Emily again, and they get married, hence the tragedy. But it’s usually things outside that happen, but fate did change their lives. Events happen to them. It seems to be that way, I think. In almost all the stories. Eberlin the same. He didn’t choose, he’s not like a man who chooses like Philip Marlowe, gets a job, I’ll go and do that. In fact Eberlin is the last person who wants the job he’s given, which is to kill himself.

I like the idea of somebody in fact who thinks they’ve got everything made and suddenly the west wind or the north wind changes.

Your books often mix fictional characters with historical events, do you have a message to impart, a comment on what’s gone before?

DM: No, I don’t think I’m a writer that preaches at all. I mean, I wouldn’t want to.

I think the books are rather romantic and perhaps a little bit pessimistic. They’re rather wistful. There’s a lot of sadness in most of the books about the characters, even with the thrillers, that the best is over. They’re people that are over-the-hill themselves or their best times are in the past or they miss something.

The characters I like in my books are not necessarily the main characters, like The Rich Boy From Chicago, I rather like the man I based on Guy Burgess’ life. In Do You Remember England? I like the man who’s based on Errol Flynn—the fading actor. Somebody who’s actually had something then finds it’s no longer there. He’s in another world now, a new society, a New Age, he doesn’t belong anymore, he’s an anachronism. I think that the characters that I feel fond of are anachronisms.

One of the characters I like very much, historical characters, is Beau Brummell. I think the best bit of writing I did, I wrote the Beau Brummell section in the Encyclopedia Britannica. When I was asked to do it, I suddenly thought wonderful there’s this anachronistic character, a man who basically hasn’t done anything in his life and yet has influenced so much.

I mean what did he do, except for invent trousers? But the books about him are legion. The man just shines out as somebody that actually achieved something then died totally in squalor. I find a kind of fondness for people who are not quite in line somehow.

Is it true you were sued for one of your books?

DM: Yes, that was Do You Remember England?. That was simply that my wife’s first husband by association saw in fact a minor four lines in the book, that because the book was very close in culture, so he sued me for libelling him. In the book, I described him as drinking, which I suppose in libellous terms means he’s an alcoholic or a drunk. I changed it, not because there was a libel suit that went on, but he did in fact sue for libel on the day of publication. The book, therefore, was withdrawn. Quite fatal. The book was six weeks in limbo. It came out and of course, by that time, the reviews were dead. I changed him to a very right-wing Tory, hunting-for-hounds man. A caricature. And he quite liked that. It wasn’t being malicious. It was the extreme of what he objected to, so I thought I better go the opposite way.

What about the voodoo novel ‘Nightshade’?

DM: That was actually because it was fun. That was after I came back form Haiti which such a kind of scary place. Being in there, darkness and drums, it’s very sexual and sensual Haiti, hot and steamy, great, wonderful flowers, Voodoo, jungle drums, and very strongly political, the Tonton Macoute. To take two people who were totally innocent, virgins, who were passionate together, seemed a nice idea and have a mystery involved and to use what I heard for the Haitian priests about zombies, people coming back from the dead, actually appearing to people, which they actually believe in, I thought was wonderful.

You might not like the book but how did your writing the series ‘Nancy Astor’ come about?

DM: A producer friend of mine from the BBC asked me if I was interested in Nancy Astor. I didn’t know anything about her at all. I was just separated from my wife and I needed to do something. It was a year’s work. Before I began I talked to John Mortimer. I said, ‘Do you know anything about Nancy Astor?’

‘Yes, she was a bitch.’

I said, ‘Would you write her biography?’

‘Not a life, no, she’s a footnote.’

So, I wrote this nine-hour footnote about this woman, who was quite bitchy.

I enjoyed doing it.

In England, they hated it. The critics loathed it. In America, they loved it. It’s now running in America and in it’s last week now. I’ve read reviews all the time, the critics adore it. I thought the Americans would hate it and the English would like it.

It was nine weeks of absolute embarrassment. Every time I picked-up a paper, there was another knocking job on Nancy. Then I did Jamaica Inn which was much better.

I’m doing a movie now, EMI, my own thriller with Brackett, it’s called Out of the Heat. A couple of Sherlock Holmes stories which I’ve written—those are fun. Then I start writing another book.

I can’t tell you about that at all except it does involve an assassin. It’s set in the States, it’s contemporary.

The new book has also got Brackett in it. Brackett is not called “Brackett” in the movie, he’s called “Yates”, because there’s a legal problem. I wrote a movie called American Made. I was going to write another Brackett story, a sequel to Somebody’s Sister as a novel, and then I was persuaded to write it by Rank. I wrote it. It was set in America. Then, when I came back from researching it and wrote the first draft and we were going to make it, Rank collapsed and stopped making films, and it was bought by 20th Century Fox. It’s still lying on a 20th Century Fox desk somewhere. They never made it, which happens to many screenplays, but there we go. They paid me the money, but it’s not really much consolation because they own the character of Brackett, the name “Brackett.” So, as a movie, I can’t use Brackett, but as a novel I can.

The novel’s called Mona, the first title was A Woman of His Acquaintance, and now it’s called In the Past. I hope to write it this summer.

Do you write every day? Do you have a schedule?

DM: No, it’s erratic. It depends on my moods, and also deadlines, and also bank overdrafts. Usual thing. But when I write, I write. I get up very early. I’m usually up by half-past-six. I write from about half-past-seven until about noon. At least I do what Raymond Chandler says, which all writers should do (which is quite right), is that I don’t do anything else. Because I don’t read newspapers (I do actually read newspapers initially), but when I start writing I don’t do anything else. And in the end of those five-hours, I hope I’ve written something, with luck I may have written quite a lot.

I write very fast and I write long-hand. On a good day four, five, six-to-ten pages. A script is about two-weeks (I mean a TV script). A screenplay about six.

How many screenplays have you written?

DM: About fifteen with about three or four that have been done.

Can you tell me about your first big BBC TV series for which you won an Emmy and a Writers’ Guild award ‘Search for the Nile’?

DM: Search for the Nile that was my second TV, the first one was an Omnibus, a ninety-minute movie about Modigliani with Peter McEnery, which was literally a dramatised film. Then I wrote Search for the Nile, which was great fun.

The BBC at that time didn’t have much money for it (they don’t have much money now), and I was paid very little, I didn’t mind that. I had to write about Livingston. I thought I might get a trip to Africa, I mean they went from Zanzibar to Lake Tanganyika. But no.

So, fine okay. Go to Geographical Society, make you a member. In fact I wrote the scripts from maps and from [Richard] Burton’s journals and from his speech journals When the team when out there to direct it, they just followed my scripts because that was their guideline. It turned out they were pretty well, they followed them, and where Burton said, ‘And then we came to a clearing,’ or ‘Then we came to a waterfall,’ ‘Then we came to a river,’ ‘Then we came to Lake Tanganyika in six days,’ yes, you did. The crew went and followed that route with the directions that Burton said.

Why shouldn’t they? Nothing had changed. But it seemed the scripts seemed to fit in quite well. They planted Kenneth Haigh down there, did his speech, moved on and there was Lake Tanganyika.

[Phone rings]

Can you talk about your last novel ‘The Rich Boy from Chicago’?

DM: It was written at a time of transition. I was living in Gloucestershire, in this large house, which is Easthill in the book, it was a huge folly of a house, Gothic. The house basically dictated the story.

I wanted to try and find an acknowledgement of that period of time, and I wanted basically to kind of see my life [through the characters]. My background is very much like [the fictional writer Henry] Bax’s though I hope Bax is not like me. Bax is very, very cynical and quite ruthless and tough. [The hero] Freddie [Geddes] is much, I hope, much more closer to the relationships that I felt at the time of marriage and also, to be honest, they begin with rather silly things. Not silly, but one has that situation when you meet somebody and you fall in love and basically, one of the first nice things you do is to talk about each other’s lives prior to that meeting. You want to know everything about that person. You are almost even jealous that that person had experiences which you weren’t privy to before. You’ve now met somebody you want to share a lot of your day with—all of your day and all of your night, and possibly your future with. And so, each person recounts a lot of what they’ve achieved, what they were up to at that particular moment, and I thought if I wrote a book, where you actually watched the progress of one person like Zinny, the young girl in it, so that the reader, by the time Zinny meets Freddie, you know a lot about Freddie, well, everything there is to know about Freddie and everything to know about Zinny. But they don’t know it themselves. They cross their paths at various points and finally when they do meet, they have questions which obviously, you know, which they’re going to say. I like that. It’s one of those things I wanted to do.

But writing the book was quite difficult. I was going through a divorce, I was going through moving, and it was broken-up by writing scripts. Nancy Astor happened half-way through that. So, a year was taken-up between that. It was quite a bit of a book to write.

The ending was going to be different. In the end of the book, Freddie’s killed accidentally in Chicago. In fact, in the original version of it, which was turned down by Viking, he meets Nathan Leopold, or arranges to meet him in Chicago. Freddie’s killed, literally, as he sees his taxi coming along with Nathan Leopold in the other car, which is very much the beginning. Leopold is sitting in the back of the car. He’s going across the street, it’s during the riots, and Freddie dies. I thought that was better linked. Then I found Leopold never went to Chicago after he was released from prison. I couldn’t think where Freddie would go? you see. There’s a point of where does a man go? Eventually in the end.

Do you feel satisfied?

DM: Are you talking about as a writer?

Yes.

DM: No, of course I don’t feel satisfied. I would have liked to have written more. I would have liked to have had a bit more energy to have written more books. I can think of a couple of books of mine I’d have re-written.

I wish two or three screenplays had been made. Madame Solari, the screenplay I wrote for that, I wish had been made. A screenplay I wrote for A Hero of Our Time, I wish that had been made.

Yes, there are things that you wish you had done. Perhaps, I suppose I wouldn’t have minded, I don’t how it would have worked out, if Dandy in Aspic had been my fourth novel, or at least, my fourth novel had had the success. I don’t say it’s hard, but it’s nice to have another bestseller in America. It’s pretty hard if it’s your first one, and you’re only twenty-four, twenty-five, and you really haven’t started writing. I’d have liked to have, I don’t say I liked to have that again, but I don’t write books like that now. I mean I may write a thriller, but I feel that if I have to do that, I may consciously have to sit-down and say, ‘Right Derek, write a bestseller. You know you can do it. You can write a thriller.’ But I’m not Stephen King, I’m not Ludlum, I’m not Elmore Leonard. I’m not those kind of writers, who’ve actually got the market on that. I just hope the kind of book I want to write, whatever it may be, is a book that’s going to make it. Because, the old adage, ‘I write for myself, but I publish for money,’ and I think money does give you the luxury to write more.

In the last five, eight-years, I’ve had to write, even though sometimes I’ve been lucky and been offered very good things in TV and movies, in order to pay for the living. I mean to pay throughout, for the kids’ school fees, I’d have liked to have earned more money out of novels than have to go and spend a lot of time writing screenplays or scripts. But I am very lucky I’ve been writing now for twenty-five years and living-off writing, which I think is a great achievement. Today, to actually just live-off writing, I feel I am pretty lucky that way. It hasn’t always been easy, but I couldn’t afford to do anything else (laughs).

Melvyn Bragg doing South Bank Show it’s terrific he does that. Not only does he do it very well, but I think it’s great that writers are able to have the opportunity to get money form other sources. I couldn’t do that kind of program. I’m not a presenter. He does it wonderfully. But now I think you have to be able to do as many things as you can. And mine is from writing scripts, but I’d like to be a pure novelist.

I’d like to be remembered as a novelist.

*****

Not long after this interview, Marlowe moved to Los Angeles where he spent his last decade writing films and scripts. He never wrote/finished his planned novel Mona. His last major work was a teleplay for a movie-length episode of Murder She Wrote called “South by South-West”.

Derek Marlowe died on the 14th of November 1996. He was fifty-eight.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.