These photographs are from the book The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals, by Charles Darwin, London 1872. Darwin was investigating the evolution of human psychology and the ways in which the human facial expression of emotion might be common across age, race and species.

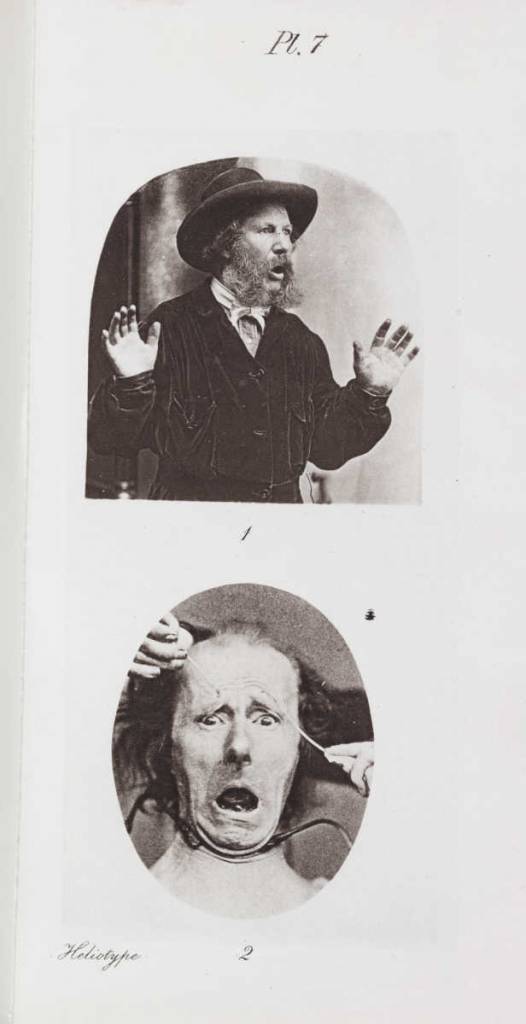

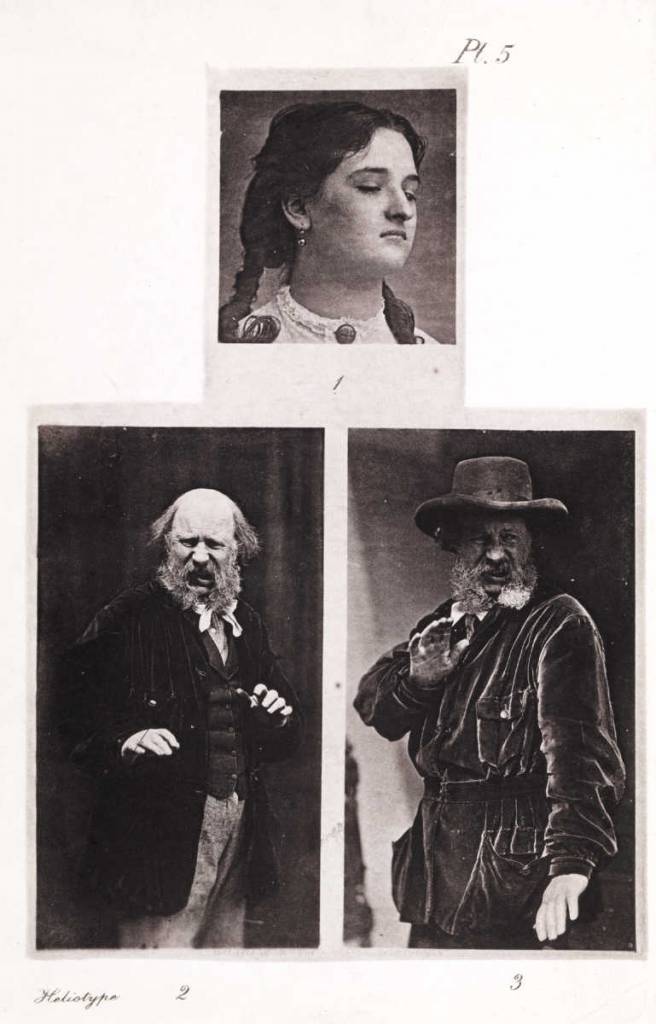

Darwin hired photographers Oscar Gustav Rejlander (1813-1875) and Adolph Diedrich Kindermann (1823-1892) to create emotional specimens. They captured human expression at a time when photography and its use in scientific books was very new. Swedish-born Rejlander used his training in fine art – Kindermann had worked as a portrait painter – to show how photography could capture the human condition and not just coldly imitate. A copy of his photograph Reclining female nude artists study, dorsal (1857) was bought by Queen Victoria as a gift for her beloved Albert after seeing it exhibited at the Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition. Rejlander’s attention to detail and the naturalness of his work brought him to Darwin’s attention.

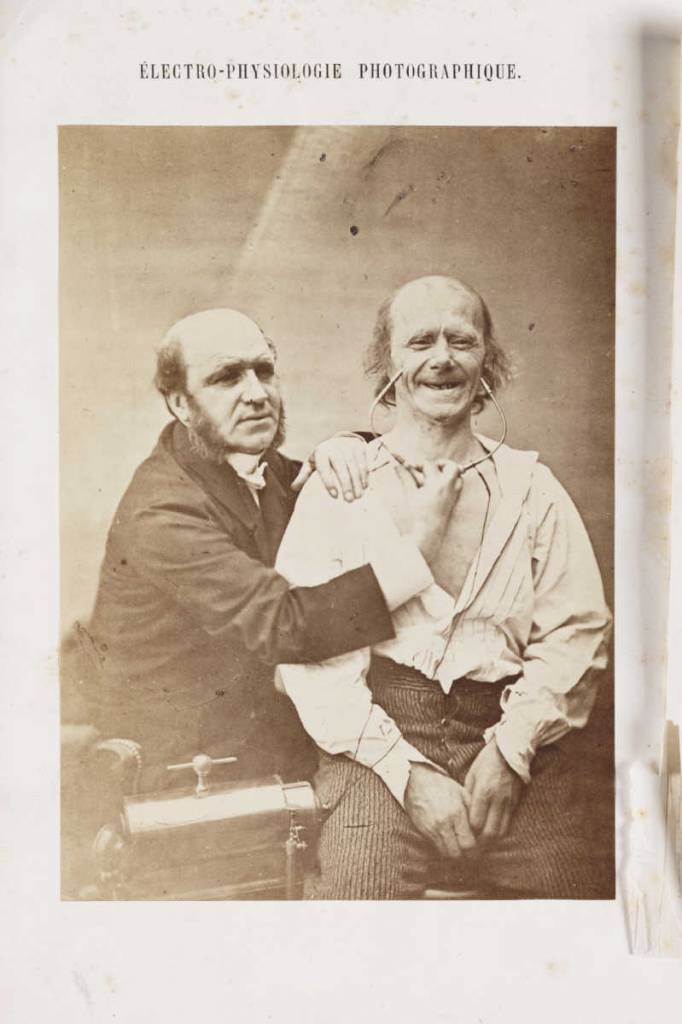

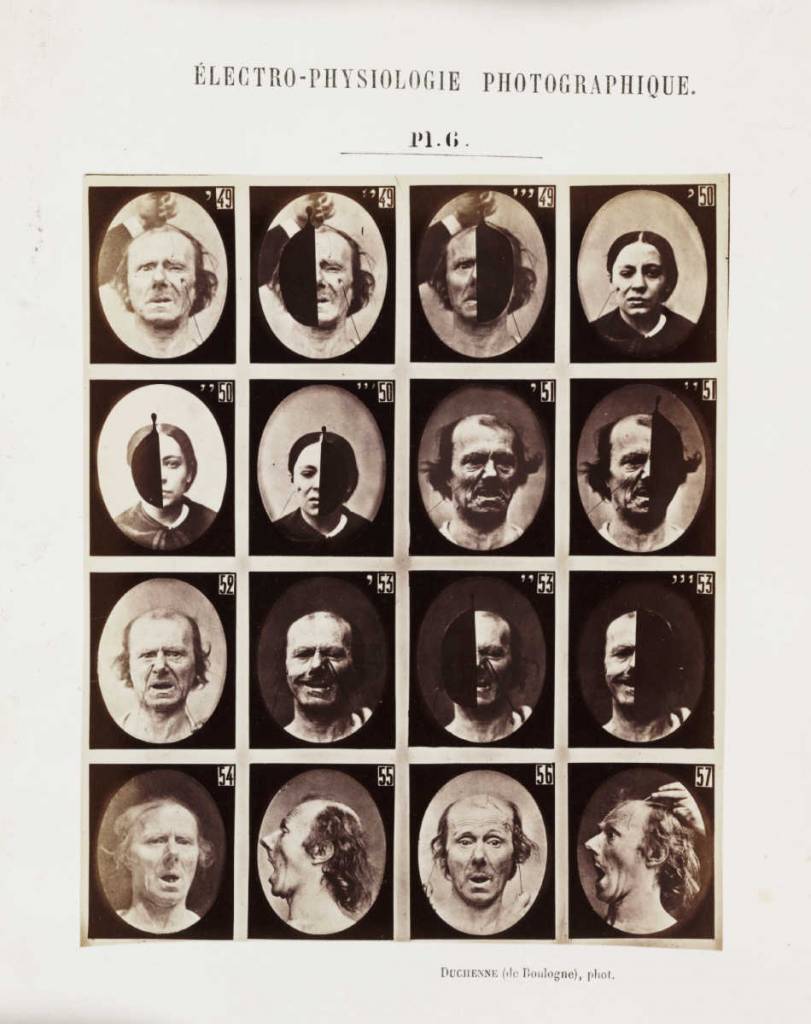

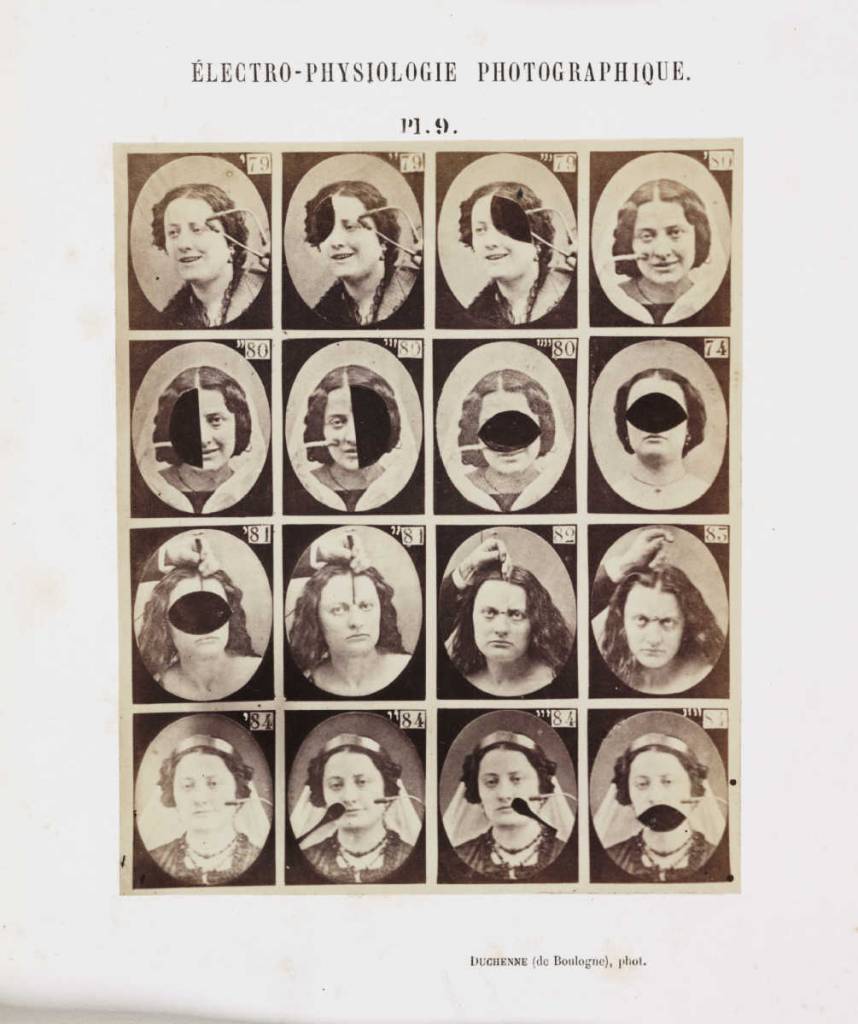

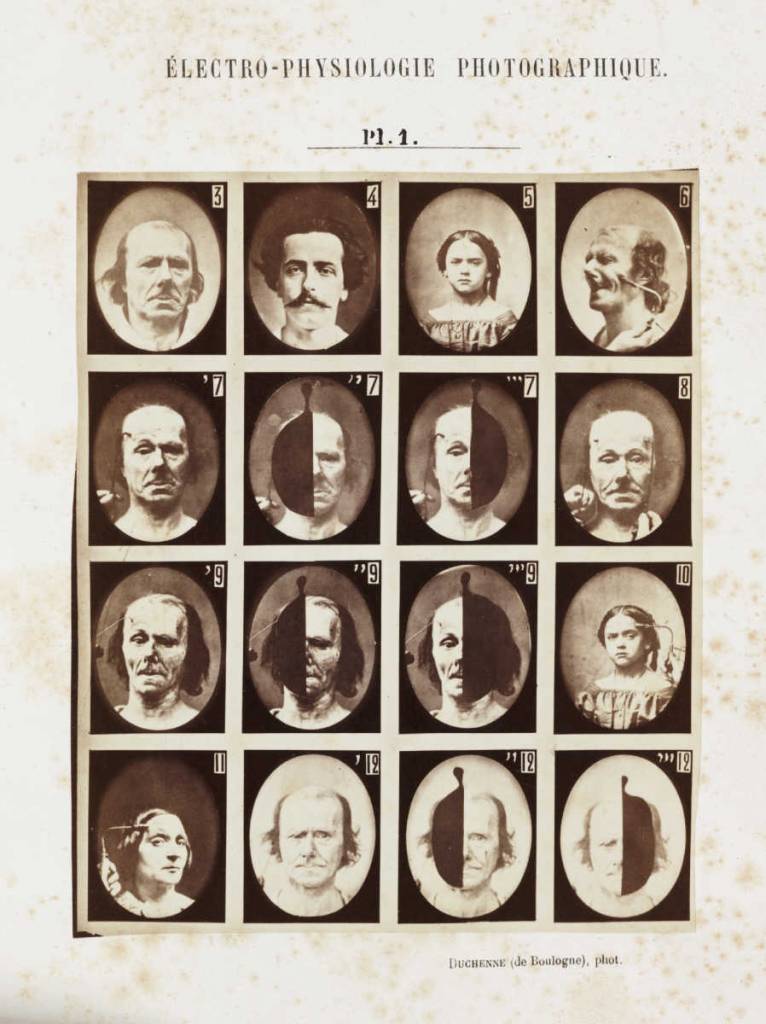

Darwin borrowed from Mecanisme de la Physionomie Humaine, by Duchenne de la Boulogne, published in Paris 1862. Duchenne was interested in the relationships between the facial muscles and expression, theories he demonstrated by electrically stimulating specific muscle groups in the face of what he called “an old, toothless, man with a thin face, whose appearance, without being precisely ugly, was more or less nondescript”. The man’s “intelligence was limited”, the neurologist noted, reducing the link between flesh and feeling.

He was also enthusiastic about the new technology, noting: “Only photography as truthful as a mirror, could attain such desirable perfection.” To Duchenne, expressions were “gymnastics of the soul”. Through them you could glimpse the Divine.

From March to November 1868, Darwin used Duchenne’s pictures in an experiment at Down House, his home in Kent. Darwin invited his guests to respond to the pictures, asking them to jot down on paper which human emotions were being portrayed in each of Duchenne’s stills. As one guest explained in a letter: “Mr Darwin brought in some photographs taken by a Frenchman, galvanising certain muscles in an old man’s face, to see if we read aright the expression that putting such muscles in play should produce.”

Darwin wrote:

Dr. Duchenne galvanized, as we have already seen, certain muscles in the face of an old man, whose skin was little sensitive, and thus produced various expressions which were photographed on a large scale. It fortunately occurred to me to show several of the best plates, without a word of explanation, to above twenty educated persons of various ages and both sexes, asking them, in each case, by what emotion or feeling the old man was supposed to be agitated; and I recorded their answers in the words which they used.

Darwin was not looking for God. The Darwin Project says:

Darwin was endlessly curious and we hope to provoke curiosity too. Are there core emotions? What are they and how many? Why do we express emotion in the way we do? How do we recognise it and can we be sure we all mean the same things? Is the expression of emotion innate? Or is it culturally modified? How do we equate different words to describe emotion (even in one language, let alone across different languages)? Can a static image ever convey emotion accurately? How do actors and artists convey it? These are all questions that Darwin was beginning to address and into which there is a great deal of current research.

What if expression is the manifestation of the physical? William James (January 11, 1842–August 26, 1910) considered this in his 1884 essay What is an Emotion?.

Our natural way of thinking about these standard emotions is that the mental perception of some fact excites the mental affection called the emotion, and that this latter state of mind gives rise to the bodily expression. My thesis on the contrary is that the bodily changes follow directly the PERCEPTION of the exciting fact, and that our feeling of the same changes as they occur IS the emotion.

Common sense says, we lose our fortune, are sorry and weep; we meet a bear, are frightened and run; we are insulted by a rival, are angry and strike. The hypothesis here to be defended says that this order of sequence is incorrect, that the one mental state is not immediately induced by the other, that the bodily manifestations must first be interposed between, and that the more rational statement is that we feel sorry because we cry, angry because we strike, afraid because we tremble, and not that we cry, strike, or tremble, because we are sorry, angry, or fearful, as the case may be. Without the bodily states following on the perception, the latter would be purely cognitive in form, pale, colourless, destitute of emotional warmth. We might then see the bear, and judge it best to run, receive the insult and deem it right to strike, but we could not actually feel afraid or angry…

If we fancy some strong emotion, and then try to abstract from our consciousness of it all the feelings of its characteristic bodily symptoms, we find we have nothing left behind, no “mind-stuff” out of which the emotion can be constituted, and that a cold and neutral state of intellectual perception is all that remains.

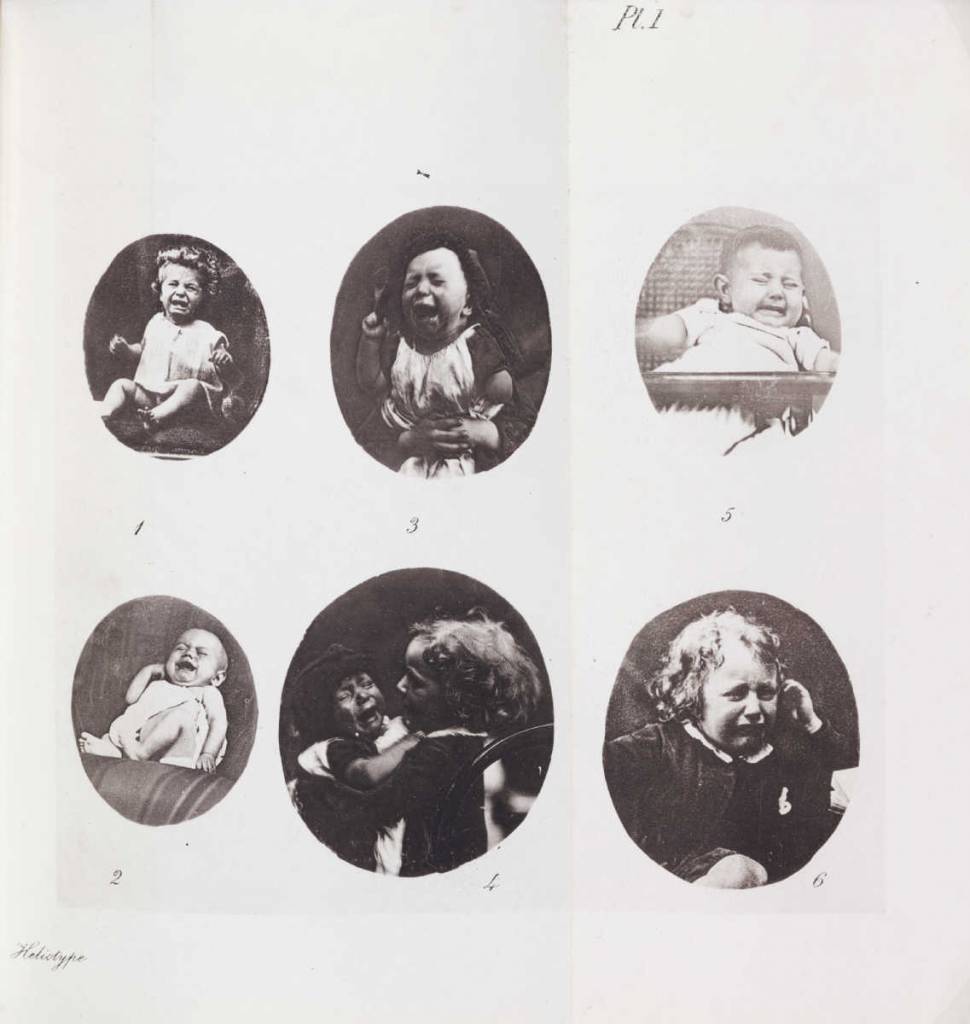

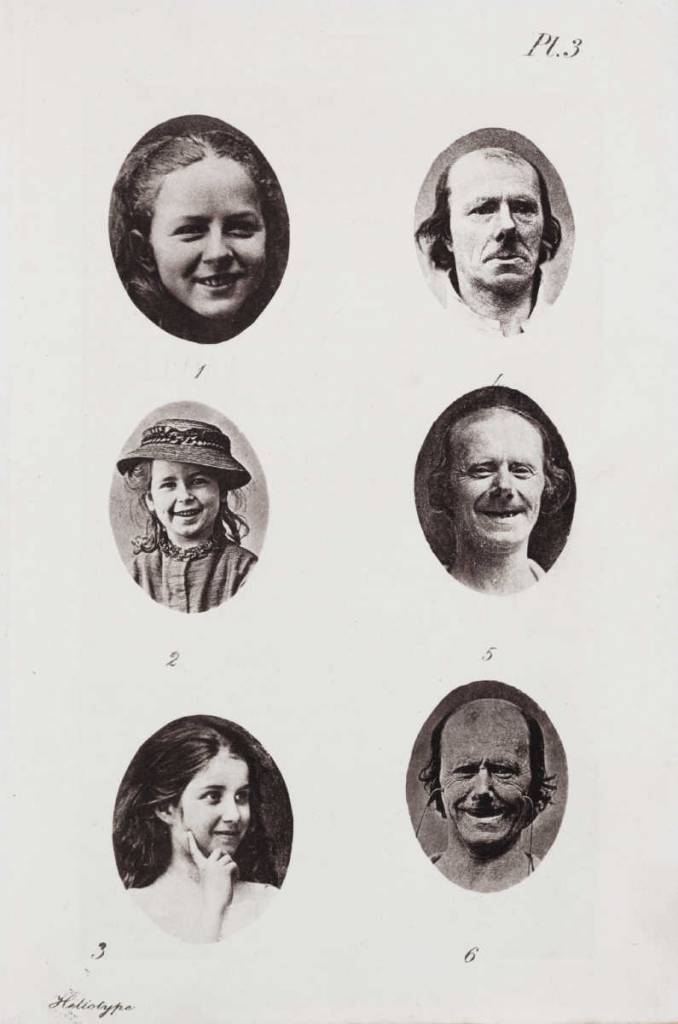

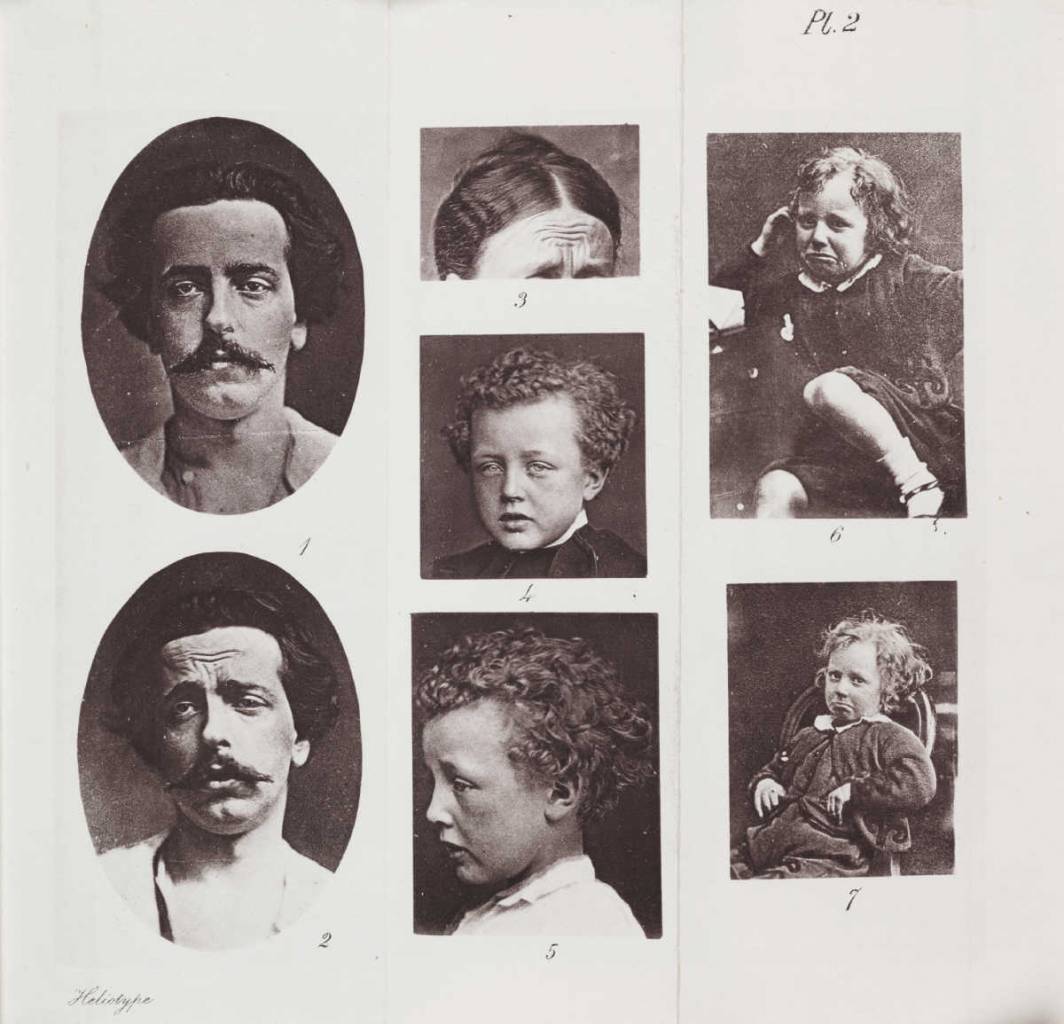

‘Expressions of Suffering – Weeping’ from ‘The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals’ London 1872. Charles Darwin (1809-1882)

‘Helplessness’ from ‘The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals’ London 1872. Charles Darwin (1809-1882). Stills 2,3 and 4 are of Rejlander.

We don’t all see the same things. Oliver Sachs recalled:

In 1985, I published a case history called “The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat,” about Dr. P., who had a very severe visual agnosia. He was not able to recognize faces or their expressions. Moreover, he could not identify, or even categorize, objects; thus, he was unable to recognize a glove, to distinguish it as an article of clothing, or to perceive that it resembled a hand.

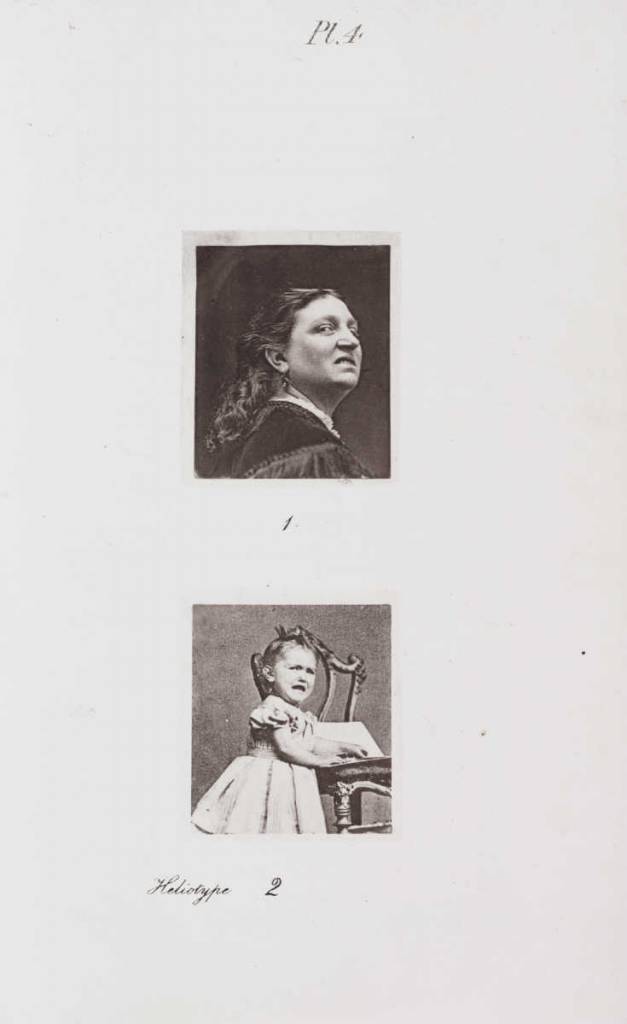

‘Sneering and Defiance’ from ‘The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals’ London 1872. Charles Darwin (1809-1882)

‘Contempt’ from ‘The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals’ London 1872. Charles Darwin (1809-1882)

‘Expression of Joy’ from ‘The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals’ London 1872. Charles Darwin (1809-1882)

‘Expressions of Grief’ from ‘The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals’ London 1872. Charles Darwin (1809-1882)

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.