“– you know, I’ve either had a family, a job,

something has always been in the

way

but now

I’ve sold my house, I’ve found this

place, a large studio, you should see the space and

the light.

for the first time in my life I’m going to have

a place and the time to

create”

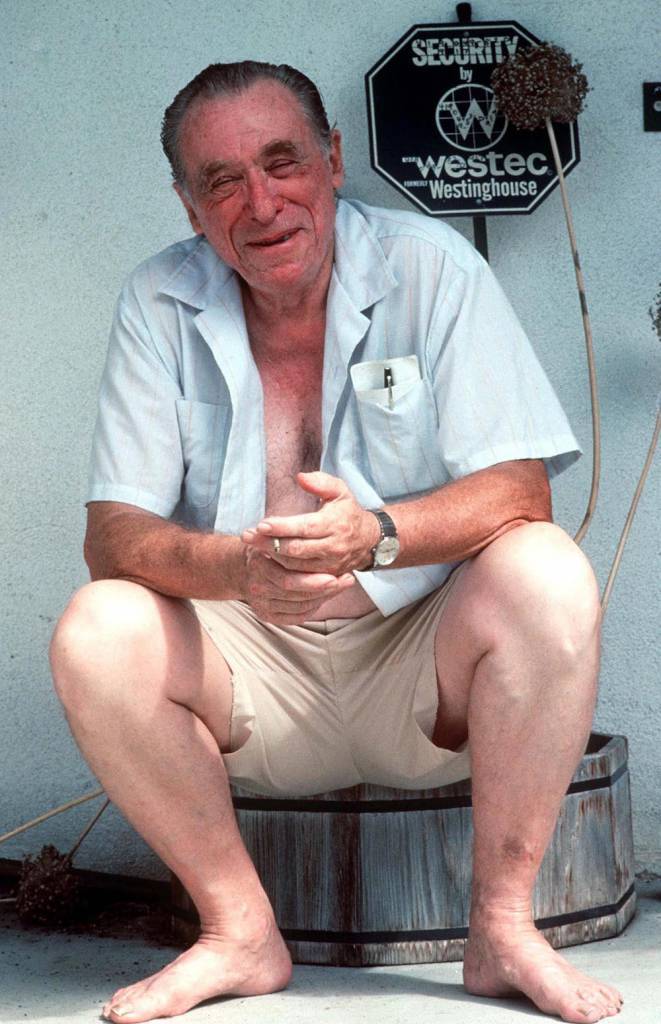

– Charles Bukowski, Air And Light And Time And Space

Before writing became a full-time job that paid, Charles Bukowski was a working stiff, earning a wage in a pickle factory and as a fill-in mailman for the U.S. Postal Service, then later for over a decade as a filing clerk. In 1969, at age 49, Black Sparrow Press publisher John Martin made him offer: quite your job and I’ll pay you $100 a month for life to write.

Bukowski accepted the offer.

It was an investment not without risk. Martin started Black Sparrow to publish Bukowski, initially as a part-time operation he ran after his own $400-a-month 9-5 job ended. Paying a quarter of his own wage to the writer was a punt, albeit well considered. “We sat down with a little piece of paper,” Martin recalled in 2014. “I sat there with a pen, and he listed out all of his monthly expenses – and you’ve got to remember… his rent was $35 a month. He had $15 in child support, $3 for cigarettes, $10 for liquor, and another $15 for food.”

In 1971, Black Sparrow Press published Bukowki’s first novel. He called it Post Office

“At the very end, I paid him a retainer so I wouldn’t owe him some horrible amount of money,” adds Martin. “Eventually I paid him $10,000 every two weeks. So he went from $100 every month to $10,000 every two weeks, and then, at the end of the year, I’d make up whatever I still owed him. Later, the really big money came in when we started to sell his books for movies and stuff like that.”

His hunch that Bukowski was “the new Walt Whitman” paid off.

On August 12 1986, Bukowski wrote John a letter of thanks. This is it:

8-12-1986

Hello John:

Thanks for the good letter. I don’t think it hurts, sometimes, to remember where you came from. You know the places where I came from. Even the people who try to write about that or make films about it, they don’t get it right. They call it “9 to 5.” It’s never 9 to 5, there’s no free lunch break at those places, in fact, at many of them in order to keep your job you don’t take lunch. Then there’s overtime and the books never seem to get the overtime right and if you complain about that, there’s another sucker to take your place.

You know my old saying, “Slavery was never abolished, it was only extended to include all the colors.”

And what hurts is the steadily diminishing humanity of those fighting to hold jobs they don’t want but fear the alternative worse. People simply empty out. They are bodies with fearful and obedient minds. The color leaves the eye. The voice becomes ugly. And the body. The hair. The fingernails. The shoes. Everything does.

As a young man I could not believe that people could give their lives over to those conditions. As an old man, I still can’t believe it. What do they do it for? Sex? TV? An automobile on monthly payments? Or children? Children who are just going to do the same things that they did?

Early on, when I was quite young and going from job to job I was foolish enough to sometimes speak to my fellow workers: “Hey, the boss can come in here at any moment and lay all of us off, just like that, don’t you realize that?”

They would just look at me. I was posing something that they didn’t want to enter their minds.

Now in industry, there are vast layoffs (steel mills dead, technical changes in other factors of the work place). They are layed off by the hundreds of thousands and their faces are stunned:

“I put in 35 years…”

“It ain’t right…”

“I don’t know what to do…”

They never pay the slaves enough so they can get free, just enough so they can stay alive and come back to work. I could see all this. Why couldn’t they? I figured the park bench was just as good or being a barfly was just as good. Why not get there first before they put me there? Why wait?

I just wrote in disgust against it all, it was a relief to get the shit out of my system. And now that I’m here, a so-called professional writer, after giving the first 50 years away, I’ve found out that there are other disgusts beyond the system.

I remember once, working as a packer in this lighting fixture company, one of the packers suddenly said: “I’ll never be free!”

One of the bosses was walking by (his name was Morrie) and he let out this delicious cackle of a laugh, enjoying the fact that this fellow was trapped for life.

So, the luck I finally had in getting out of those places, no matter how long it took, has given me a kind of joy, the jolly joy of the miracle. I now write from an old mind and an old body, long beyond the time when most men would ever think of continuing such a thing, but since I started so late I owe it to myself to continue, and when the words begin to falter and I must be helped up stairways and I can no longer tell a bluebird from a paperclip, I still feel that something in me is going to remember (no matter how far I’m gone) how I’ve come through the murder and the mess and the moil, to at least a generous way to die.

To not to have entirely wasted one’s life seems to be a worthy accomplishment, if only for myself.

yr boy,

Hank

It’s never too late to change course.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.