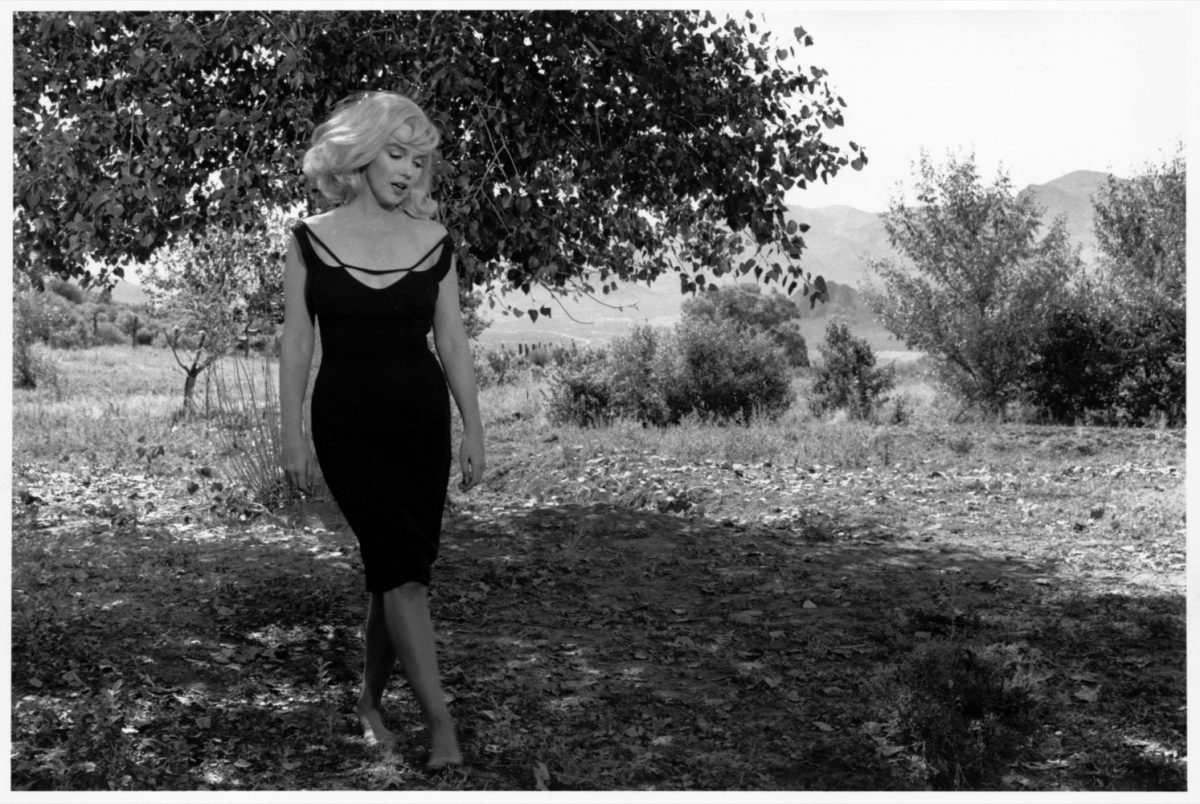

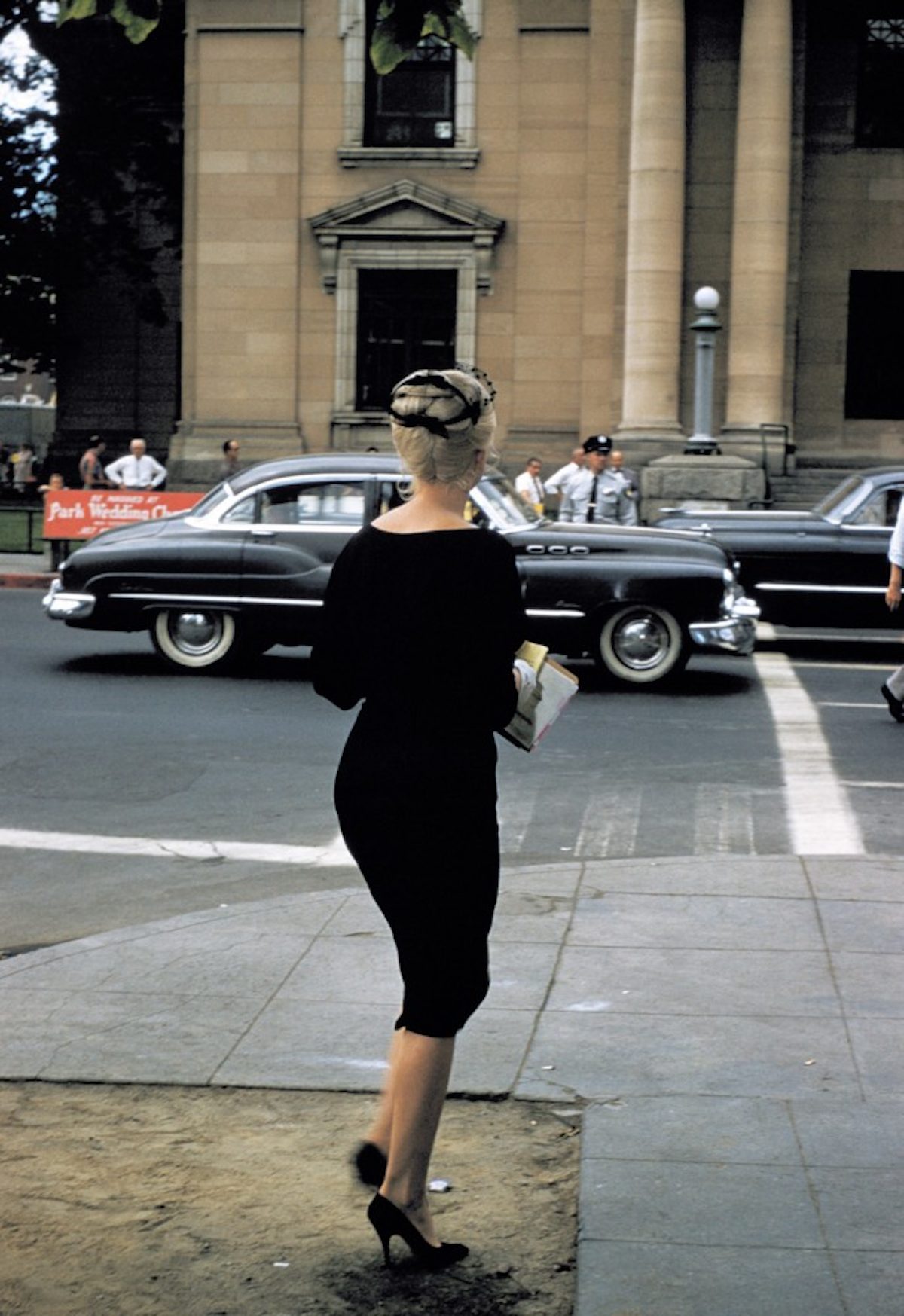

USA. Reno, Nevada. 1960. Set of “The Misfits.” Marilyn MONROE

There are films that are legendary for their greatness; films that are legendary for tragic events outside the frame—sad facts we read about with prurient interest decades later; and films that are, somehow, despite all odds, both great and grimly tragic at the same time. John Huston’s 1961 The Misfits, written by Arthur Miller and starring his soon-to-be ex-wife Marilyn Monroe, must top the last list in most critics’ estimation.

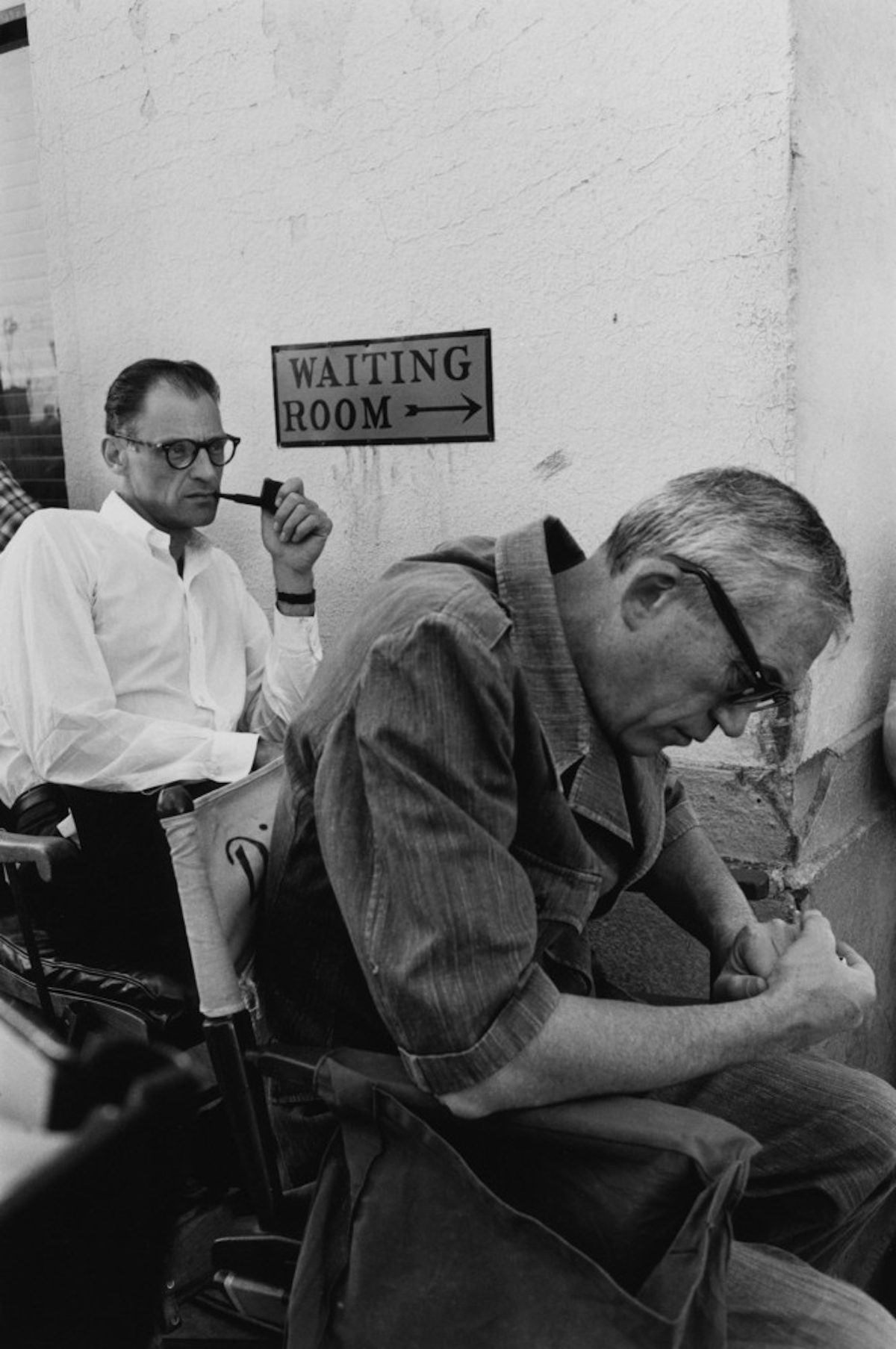

The film should not have worked. Miller, who wrote the screenplay as a “valentine” to his wife, “had next to no experience as a writer for the screen,” notes Geoff Andrew at BFI. “Monroe was in many ways a wreck, dependent on alcohol and prescription drugs, having difficulty remembering her lines and turning up on time at the set. Director John Huston was often drunk, and apparently not averse to falling asleep on set. He would often display more interest in gambling than in the job at hand.”

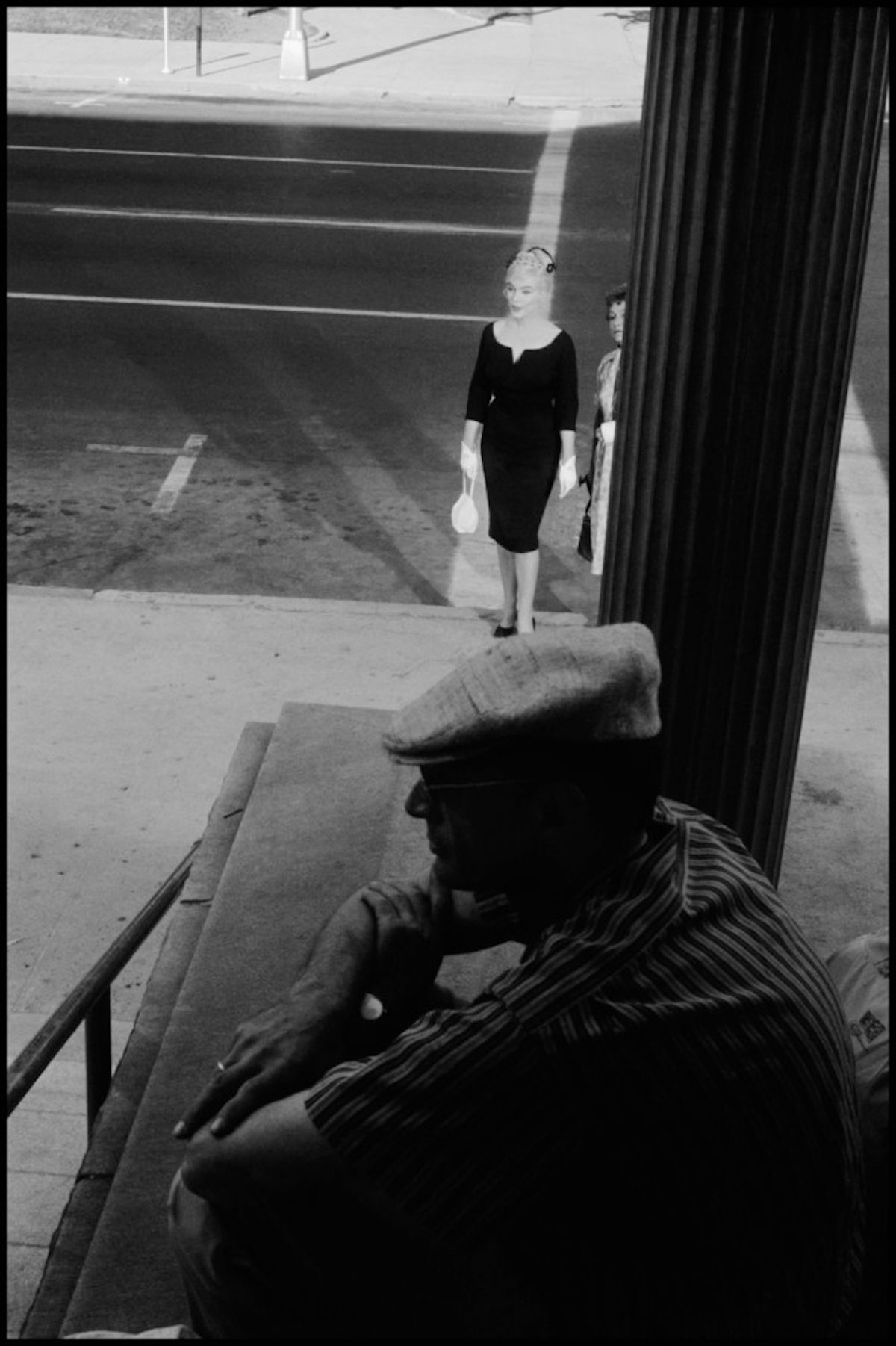

USA. Reno, Nevada. 1960. Set of “The Misfits.” Marilyn MONROE.

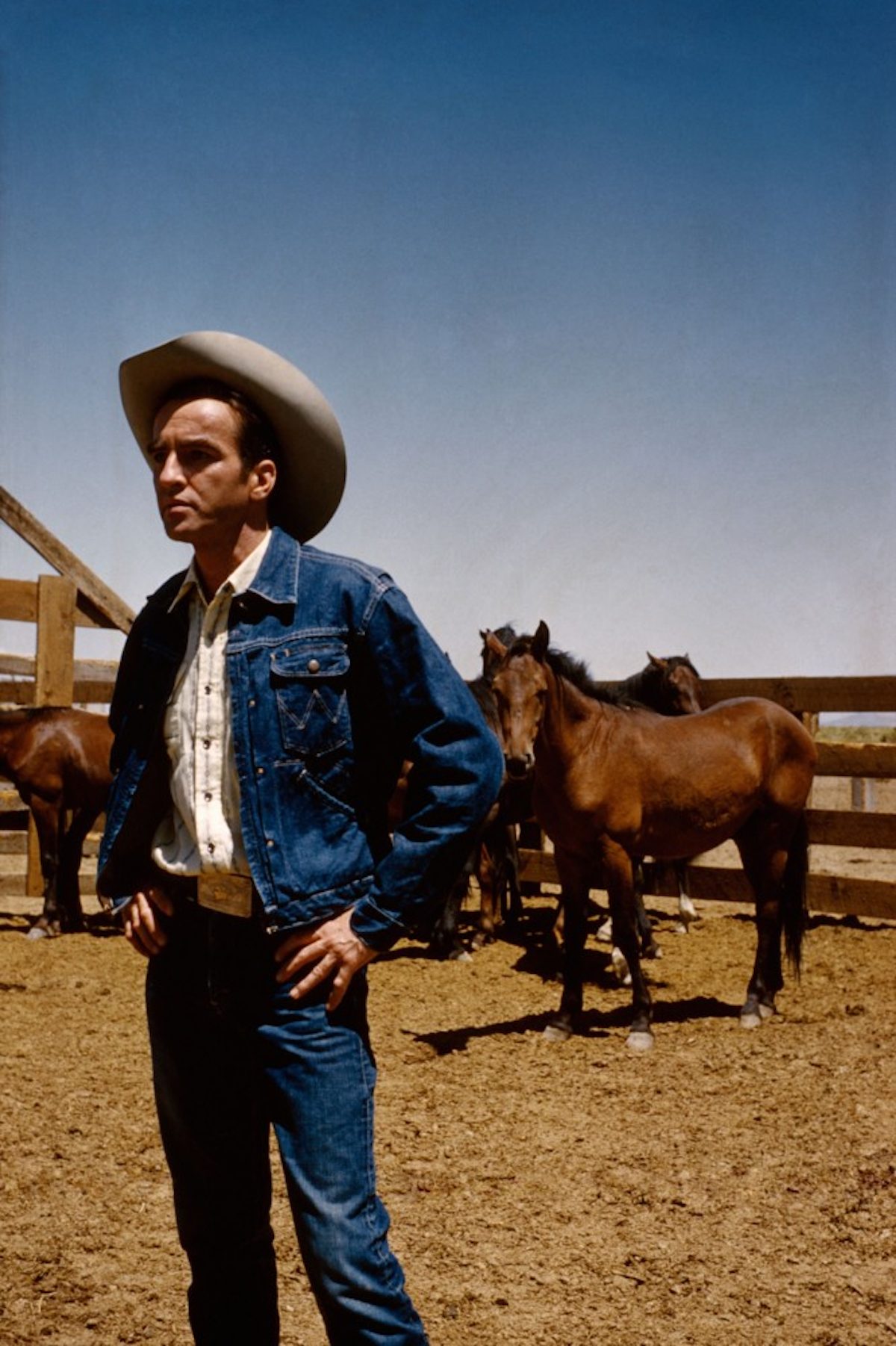

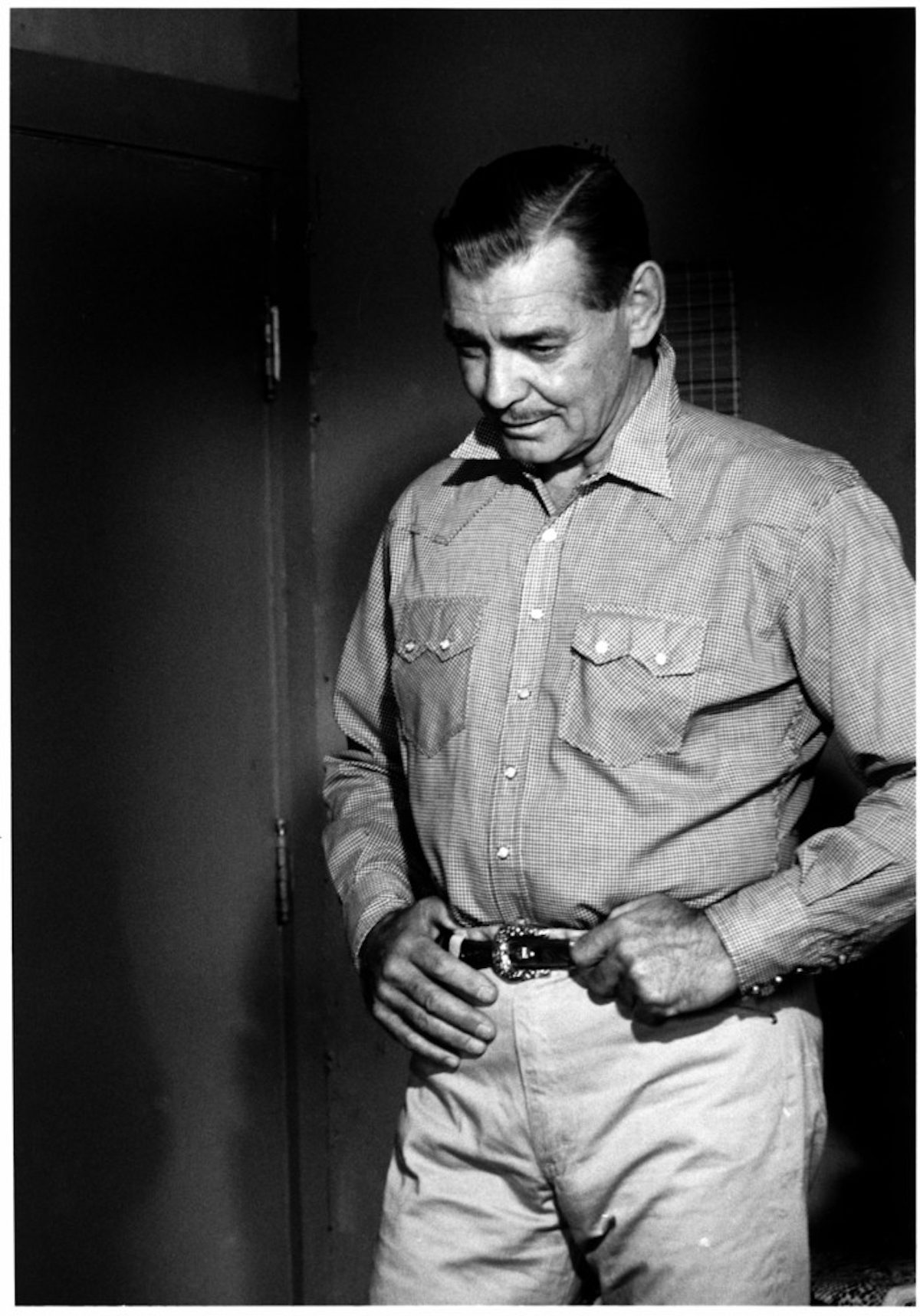

Monroe and Miller got a “Mexican divorce” days after the film’s release, just as her ex-stripper character, Roslyn Tabor, does in the film. Less than one year later, Monroe was dead. Her male co-stars fared no better. Two days after the film wrapped, Clark Gable dropped dead of a massive heart attack. Montgomery Clift hung on for a few more years, but he had never been the same after injuries from a 1956 car accident that required extensive plastic surgery and left him dependent on alcohol and pills.

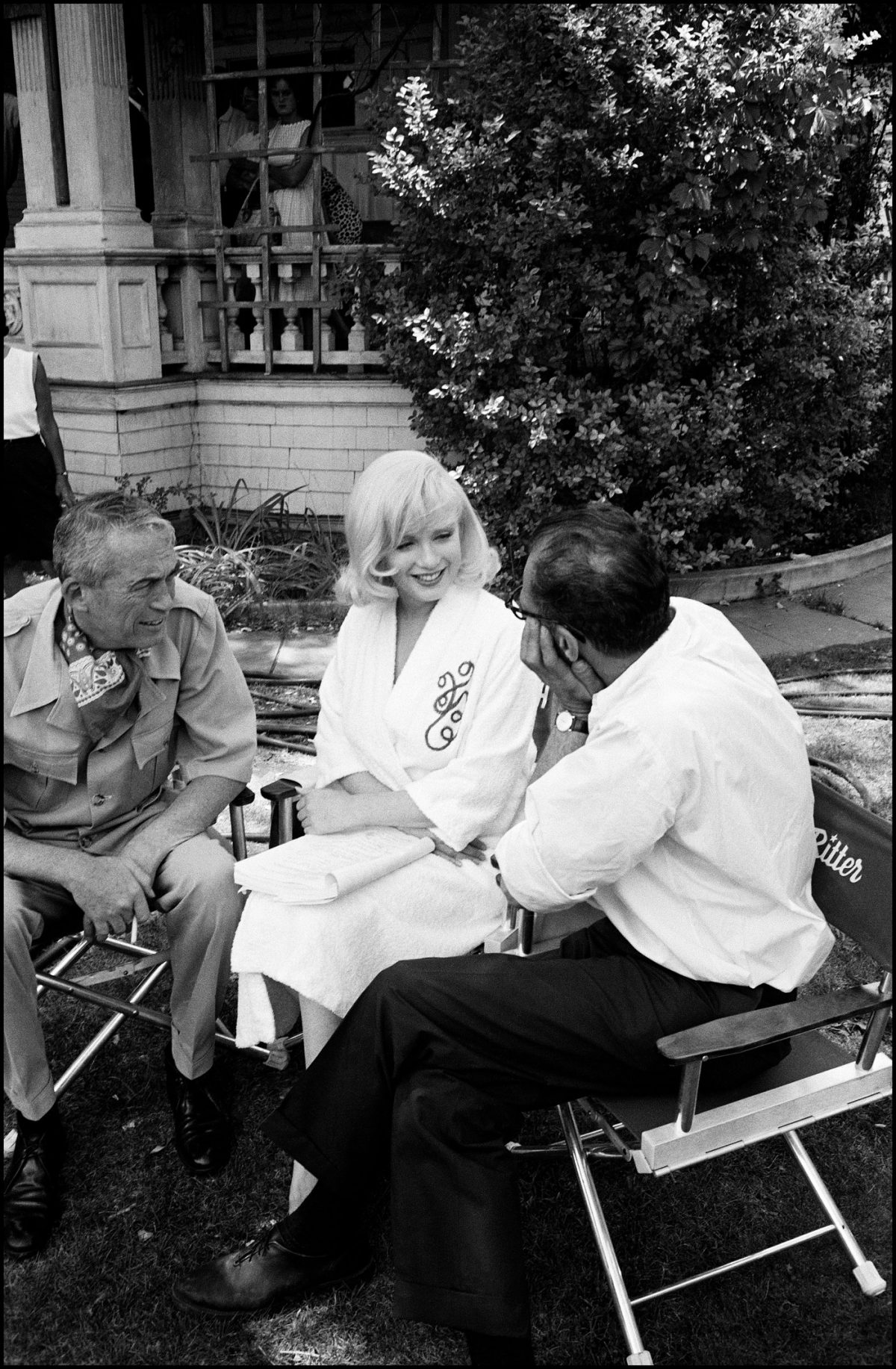

Clift would say during the filming that Monroe was “the only person I know who is in even worse shape than I am.” She had been typecast in “fluff” parts, Miller said later, and was “at that stage in her life when really nobody was about to give her a dramatic role,” though she could clearly handle one, even, and maybe especially, in her deteriorating state. The Misfits is “bleak perfection,” Carlos Valladares writes, “pathetic” in the older sense of “having the capacity to move one to compassionate pity”; “marked by sorrow or melancholy”; and just plain “sad.”

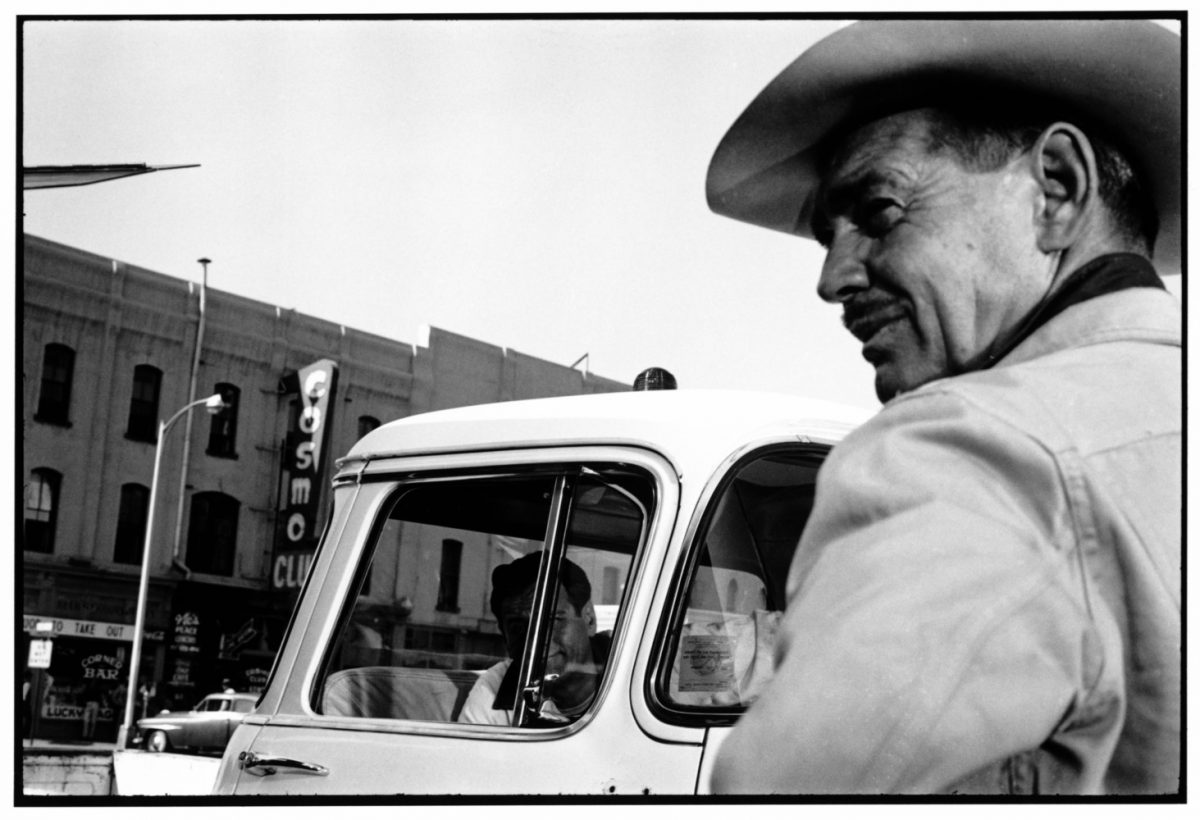

USA. Nevada. Reno. 1960. “The Misfits.” Clark GABLE and Eli WALLACH in the car.

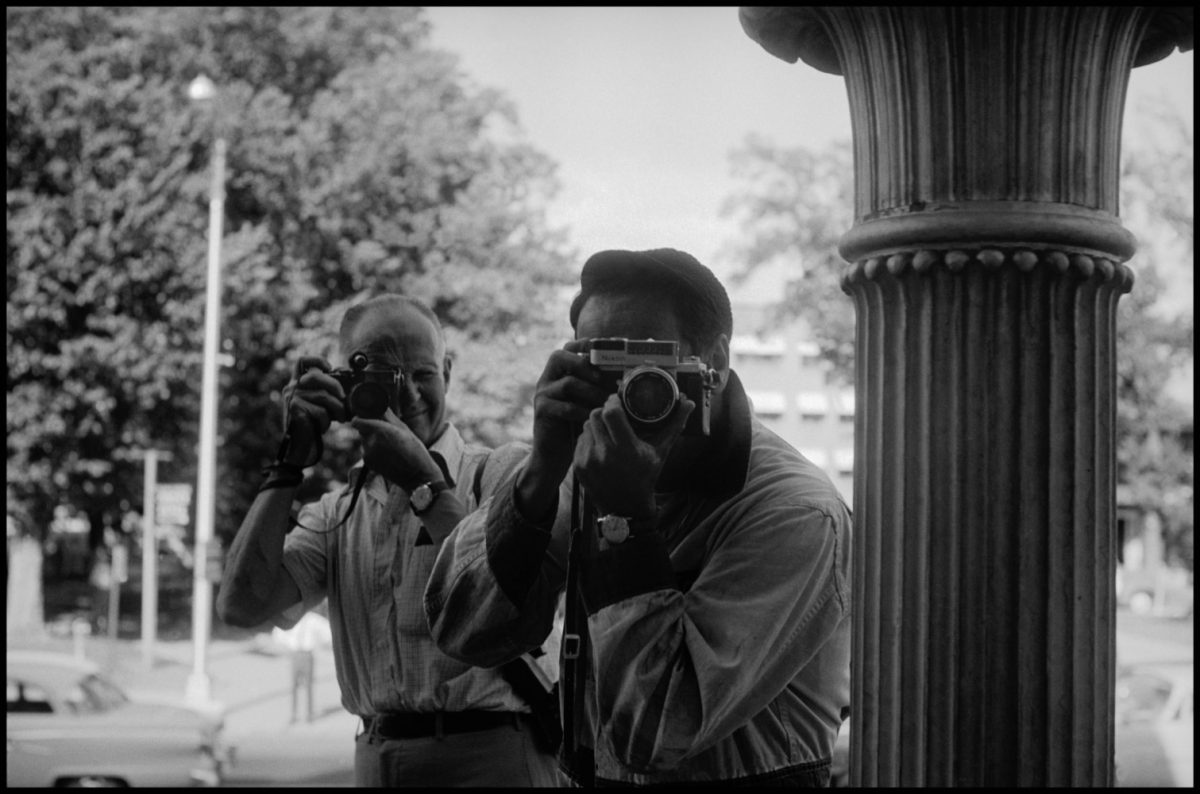

Is it possible to separate these dramatic qualities onscreen from the drama behind the camera? Probably not. But the actors’ pain gives the film its verité appeal. “Everyone has the hang-dog look of tiredness… The photographers who drifted on and off the set (Eve Arnold, Bruce Davidson, Henri Cartier-Bresson) showed off Monroe, Clift, Gable in all their un-Glamour, in a starkly honest look that would have been unthinkable in the studios’ heyday.” The Misfits not only marks the threshold of its stars’ declines, but also the implosion of the classic Hollywood era, as a grittier decade dawned and French New Wave and Italian Neorealism came to define so much of cinema’s aesthetic.

USA. Reno, Nevada. 1960. Set of “The Misfits.” Marilyn MONROE.

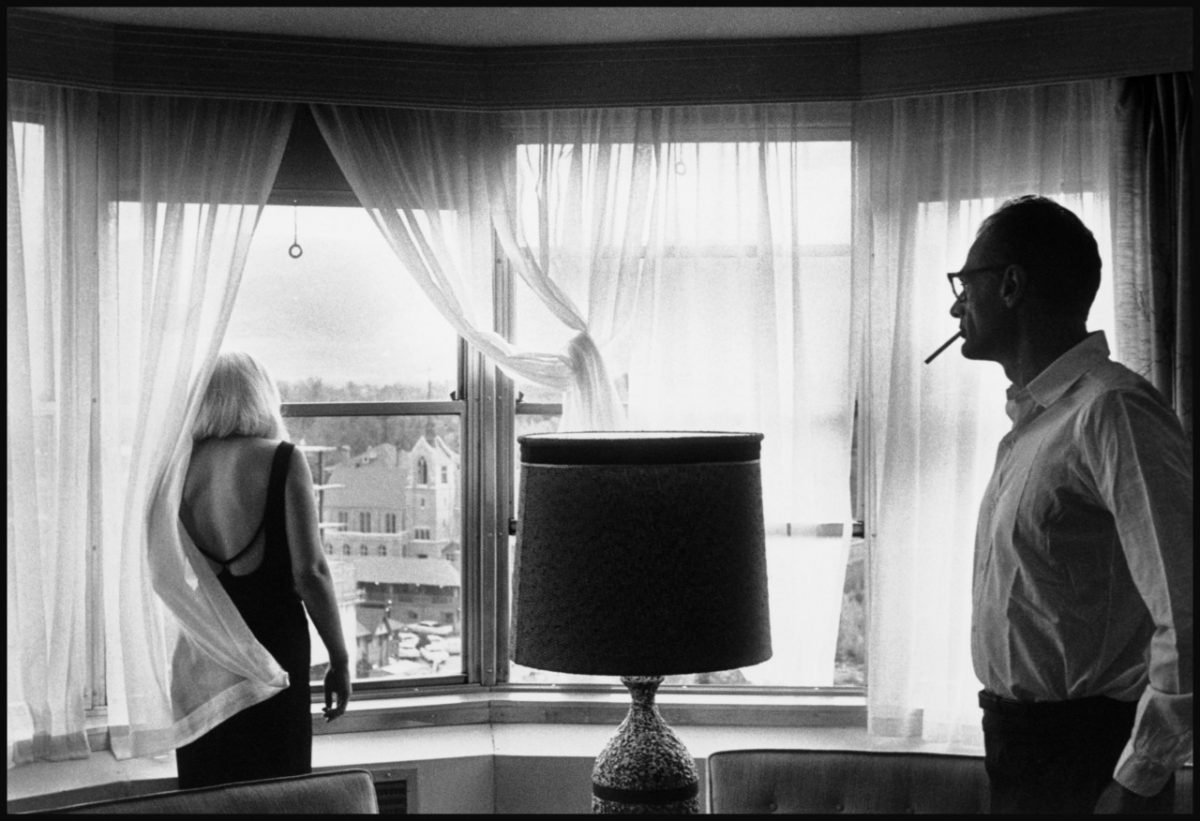

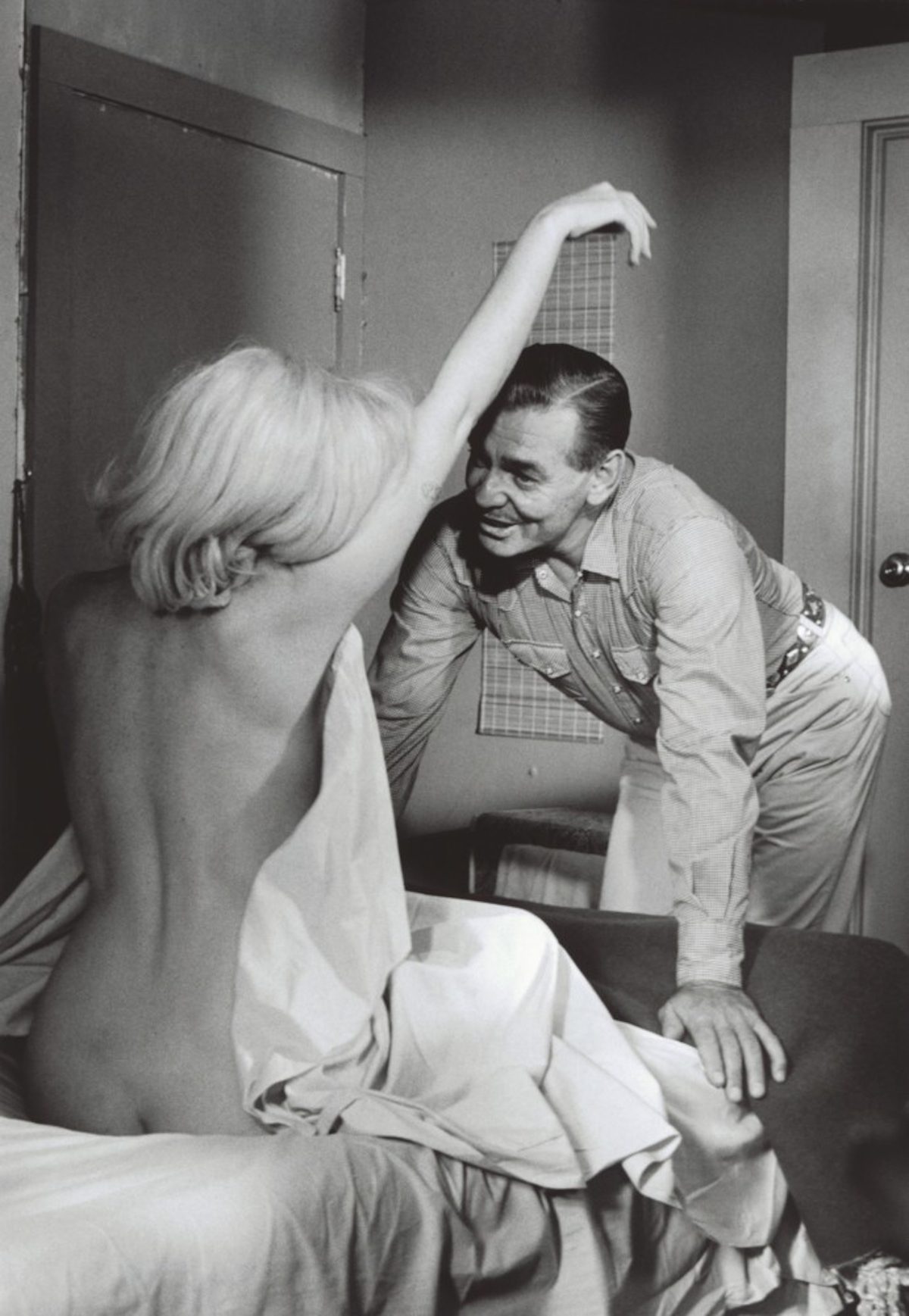

Cartier-Bresson and photographer Inge Morath drove across the country to shoot the actors on set in Reno. Morath, an Austrian, had no experience with American culture. In answer to a visa application question asking for her “color,” she wrote “pink,” Miller remembers. “She didn’t know what to make of it.” Having suffered under the Nazis, she “was quick to notice whenever that smell came up of repression and racism.” Where the other photographers on set captured the actors in several less than flattering moments, which were plentiful, Morath “took comparatively few pictures,” sensitive to her subjects’ obvious vulnerability.

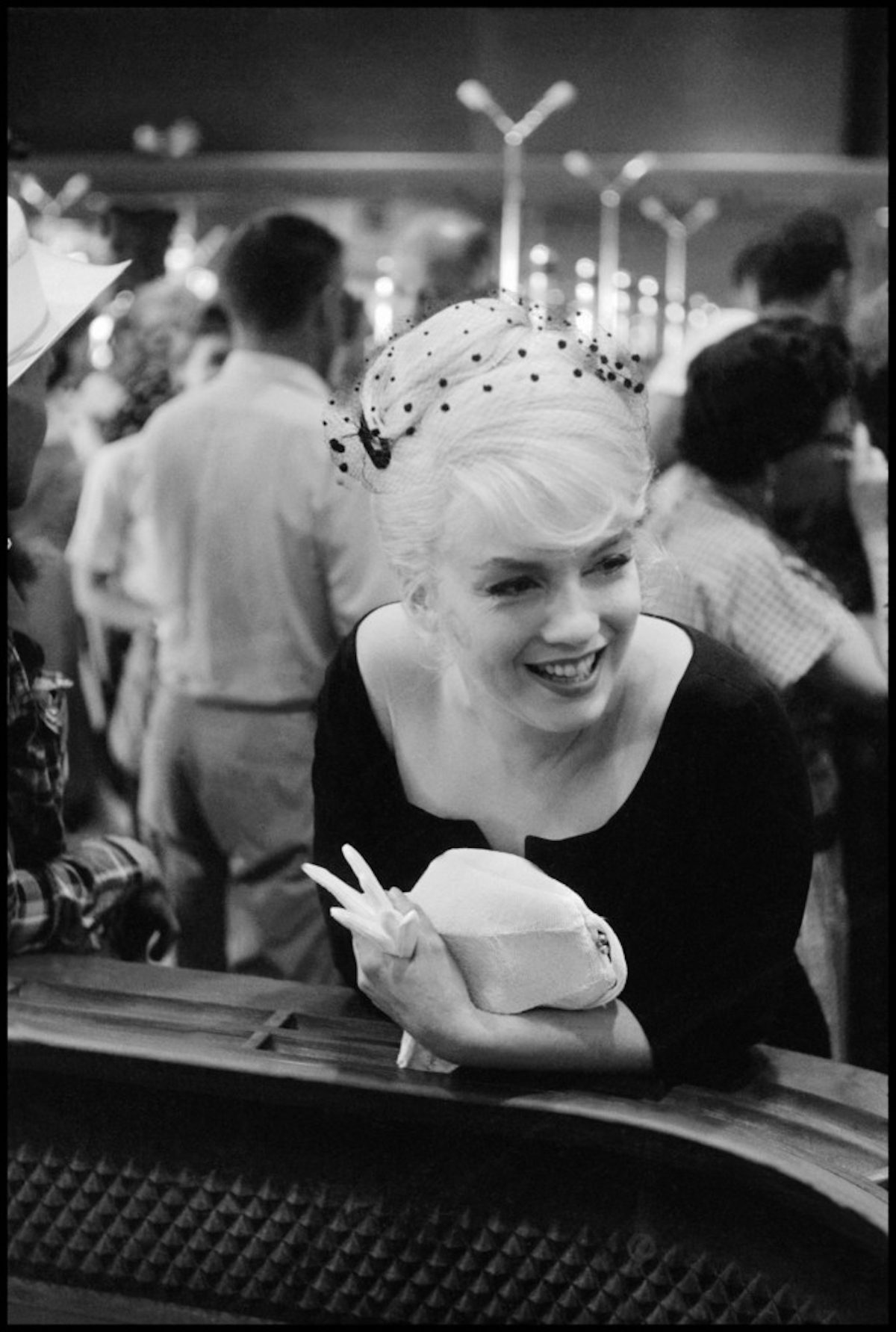

“When she pointed the camera she felt a certain responsibility for what it was looking at,” said Miller. “Her pictures of Marilyn are particularly empathetic and touching as she caught Marilyn’s anguish beneath her celebrity.” Morath herself wrote extensively in her journals of the experience: “they were all very interesting to watch. Actually, Marilyn was fascinating to watch. The way she moved, her expressions; she just was extraordinary. There was such strength and energy combined with this fragility…. You might see in some of the close-ups, behind the smile there is a tragic undertone.” The tragedy is unmistakable in the film itself, where undertone becomes overtone, and the film’s subtext, Valledares writes, of fading stars on their last legs, “is the text.”

USA. Reno, Nevada. 1960. Set of “The Misfits.” Marilyn MONROE.

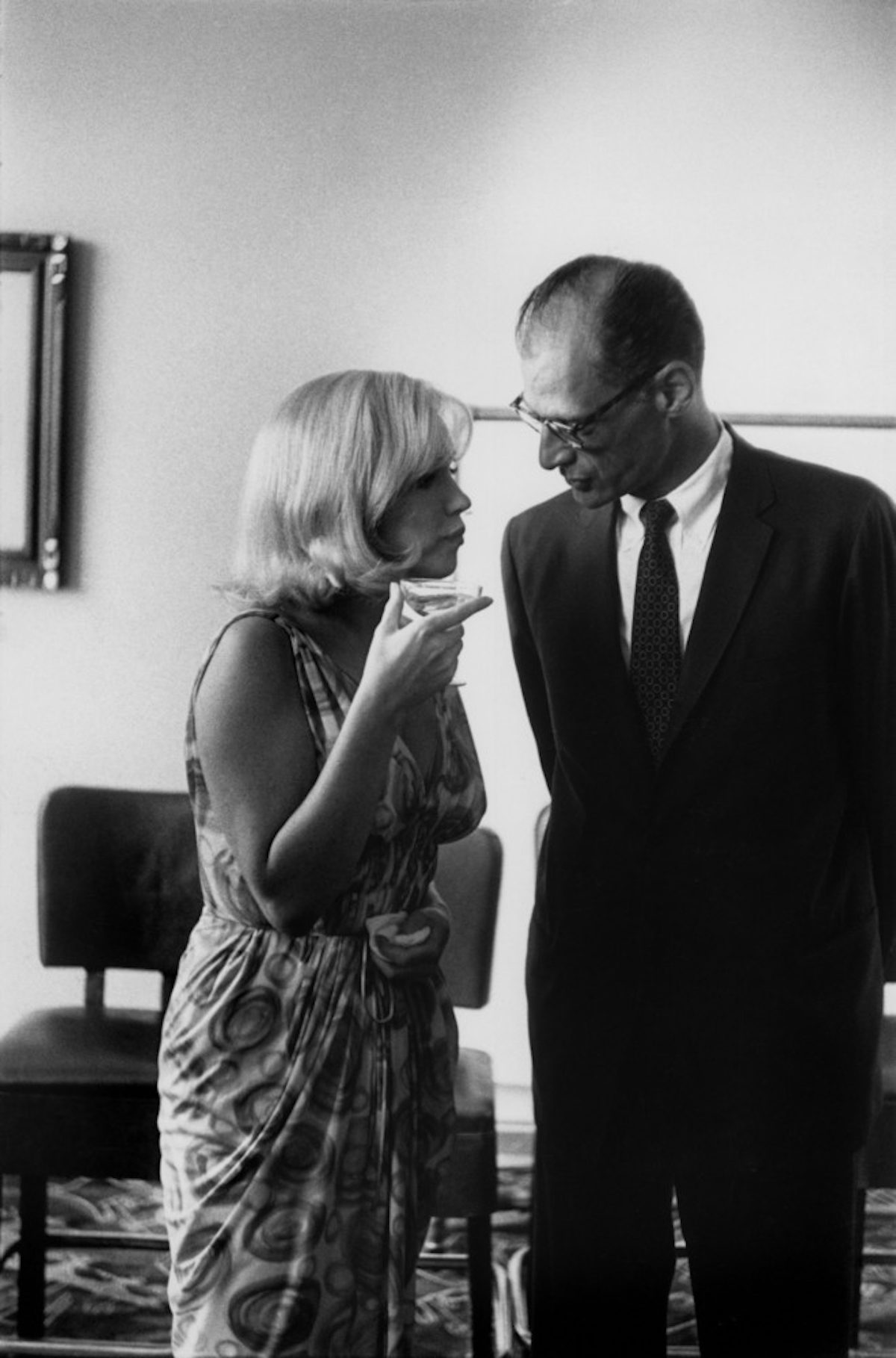

USA. Reno, Nevada. 1960. Set of “The Misfits”. Marilyn Monroe and Arthur Miller in their suite in Reno’s Mapes Hotel after a day’s shooting.

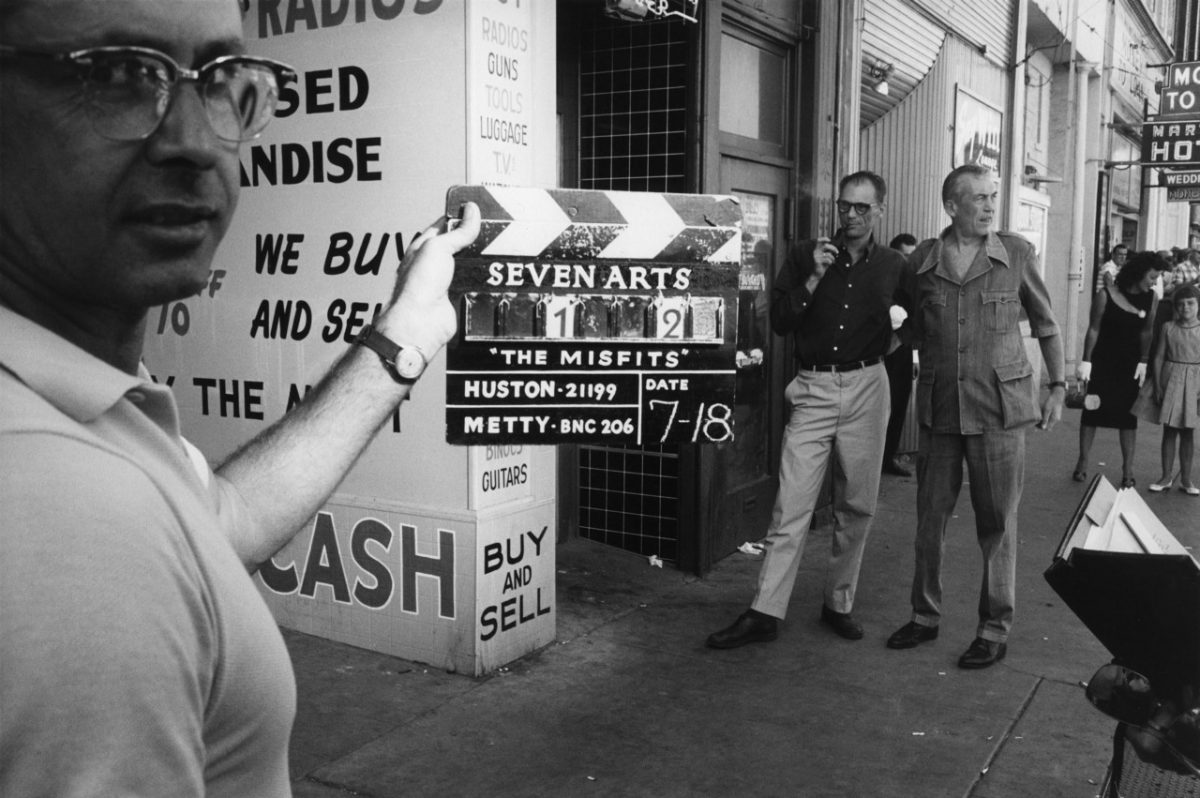

USA. Reno, Nevada. 1960. The first day of shooting “The Misfits.” Clapperboard is marked scene 1 take 2. Director John Huston and author Arthur Miller watching in the background.

USA. Beatty, Nevada. 1960. One-armed bandit.

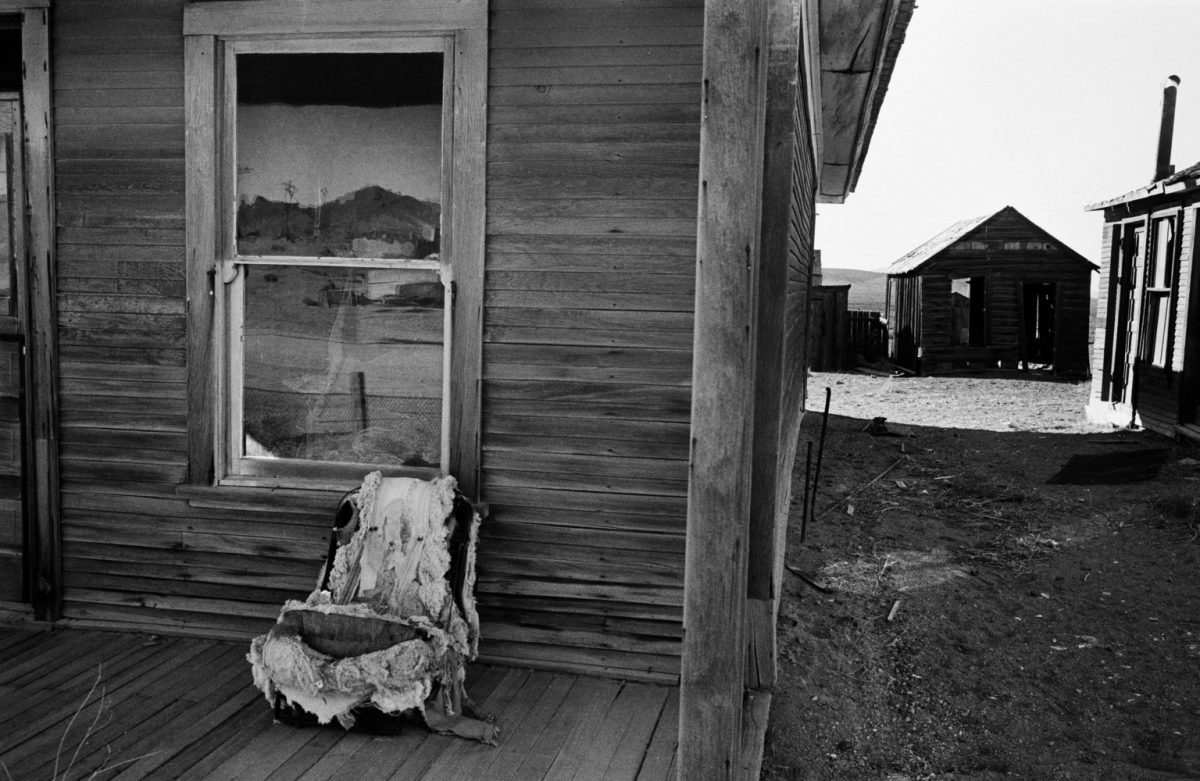

USA. Goldfield, Nevada. 1960.

Marilyn MONROE.

USA. Reno, Nevada. 1960. Set of “The Misfits”. Clark Gable and Marilyn Monroe.

USA. Reno, Nevada. 1960. “The Misfits.” Marilyn MONROE and Arthur MILLER.

USA. Reno, Nevada. 1960. Set of “The Misfits.” John Huston and Arthur Miller wait and brood over the next scene.

USA. Nevada. Reno. 1960. John Huston, Marilyn Monroe & Arthur Miller during the filming of “The Misfits”

USA. Reno, Nevada. 1960. Montgomery CLIFT on the set of “The Misfits.”

USA. Reno, Nevada. 1960. Henri CARTIER-BRESSON with actor Eli WALLACH (right) during the production of “The Misfits.”

USA. Reno, Nevada. 1960. Marilyn Monroe during the filming of “The Misfits”

USA. Reno, Nevada. 1960. Arthur MILLER (foreground) and Marilyn MONROE during the filming of “The Misfits”

USA. Reno, Nevada. 1960. Marilyn MONROE in a casino during the production of “The Misfits”

USA. Nevada. Reno. 1960. “The Misfits.” Clark GABLE

Marilyn MONROE and Elie WALLACH on the set of “The Misfits”

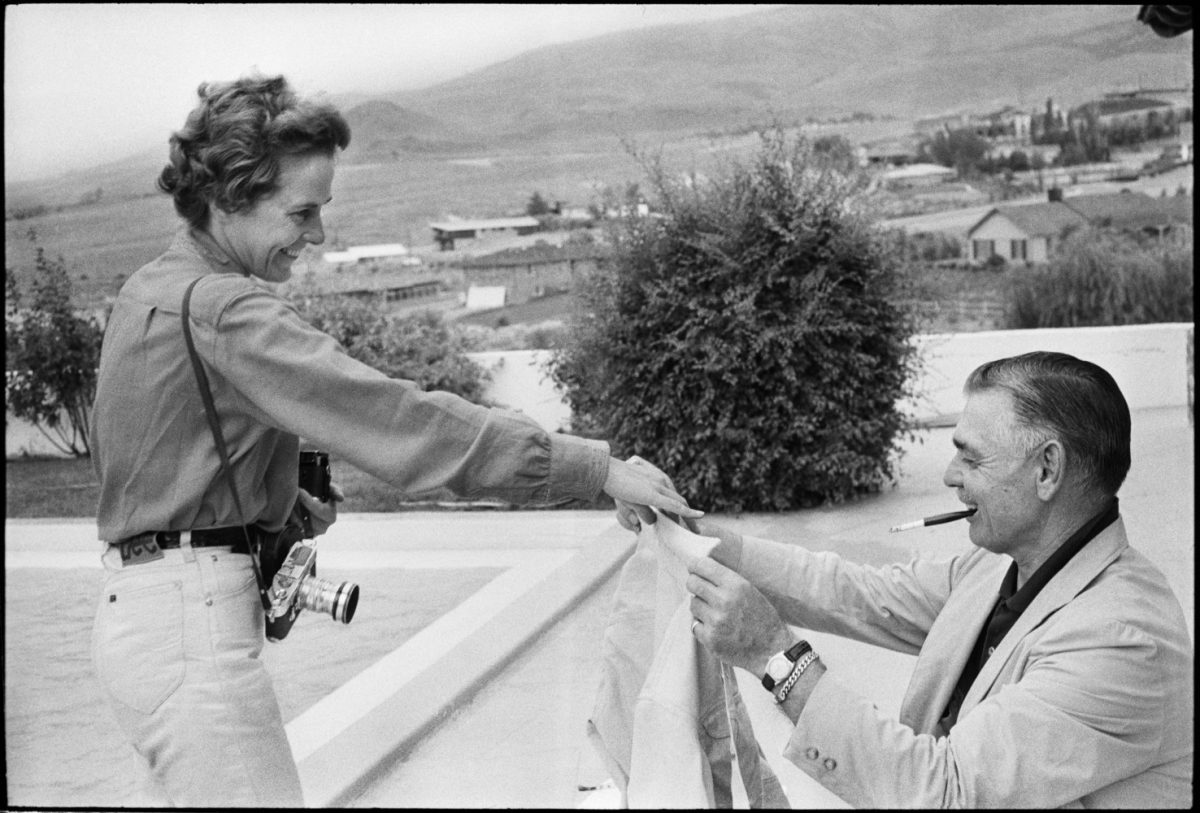

The photographer Inge MORATH and Clark GABLE

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.