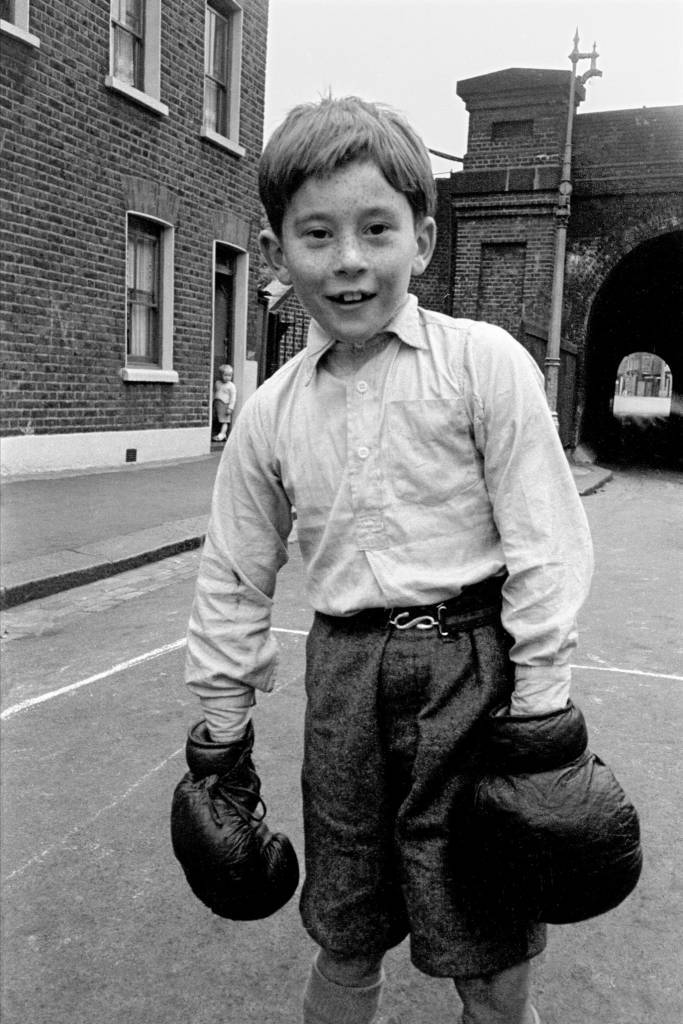

Frank Horvat’s pictures of seductively seedy Paris nightlife in 1956 are glorious. His pictures of London a year earlier captured a city with a hard edge on the cusp of a cultural revolution. Amongst that gallery are these picture of two boys fighting on a Lambeth Street.

Does anyone know the road seen in these pictures? Is that you looking on as two lads enjoying the sport? Is that you fighting?

Boxing in the 1950s was huge. Floyd Patterson, Rocky Marciano and Jake LaMotta were some of the world-famous names. In Britain, Randy Turpin won the world Middleweight title by defeating the great Sugar Ray Robinson in London.

Terry Allen was, at various times, British, Commonwealth, European and World flyweight champion.

30th January 1952: British flyweight champion Terry Allen nurses a black eye after a fight. (Photo by Express/Express/Getty Images)

Boxing was a participation sport, taught in British state schools. In 1962 it stopped. It wasn’t banned. It was no longer fashionable. If you wanted to box, you had to join a boxing club.

Dr Edith Summerskill (1901 – 1980) the English doctor and politician is pictured at West Fulham, conducting her electioneering campaign from a caravan. (Photo by Keystone/Getty Images)

Boxing was never outlawed in British schools, despite the best efforts of a physician and Labour MP called Edith Summerskill, whose anti-boxing campaign in the late Fifties and early Sixties won widespread support but lost several votes in the House of Commons. The votes may have gone against Summerskill, but the spirit of the age was with her all the way. The times were changing. Memories of the war were fading. National Service had ended. The manly virtues were going out of style. Many people believed that boxing in schools was a relic of our more violent past.

Dr Edith loathed boxing. And what she did not like must be banned.

“Can anybody sensibly suggest that the screaming crowd round a boxing ring is having implanted in it the fine qualities of pluck, endurance and restraint? We are told by those in this business that the sole object in view is to give the spectators a display of a sport regulated by rules calculated to ensure the maximum enjoyment of boxing techniques. If that is so, why are these bouts accompanied in the newspapers and on the radio by a commentary deliberately phrased to emphasise the brutal element?” – Dr Edith Summerskill, Member of Warrington – December, 17 1960

In reply:

“One could go on for ever quoting examples of sports which are dangerous to the public. If we go far enough and follow the thing to its logical conclusion, playing for absolute safety, we shall finish by being allowed to play only dumb-crambo and tiddleywinks.

“There is another aspect to the subject, the benefit to the young. Boxing keeps them fit. It keeps them off the streets. It takes them away from their flick-knives and smoking and puts them into the gymnasium. It is there that they develop self-reliance, self-control, courage and chivalry, and the ability to keep their tempers. They learn another very important thing, that if they have to fight they must fight in one place only, in the ring, against an evenly matched opponent.

“Boxing is the most popular sport on television and I refute the right hon. Lady’s suggestion that our public is becoming sadistic. I have done my best to show how we on the British Board of Boxing Control avoid all the evils alleged by the right hon. Lady and to defend professional boxing which others are trying to destroy. How easy it is to pull something down. It is not so easy to build it up again” – Lieut-Colonel Sir Walter Bromley-Davenport , Knutsford

Summerskill would later claims that watching violence breeds violence:

“Does the Postmaster-General think that frequent displays of professional boxing which glamorise brutality implant fine qualities in our young people?”

It might have been an early example of a moral panic. The young and working classes were not able to think for themselves. They were a riot waiting to happen. They needed controlling. It’s pretty much how today’s elite view football supporters.

Boxing was a ‘noble art’, a force for social cohesion to build a lad’s self confidence.

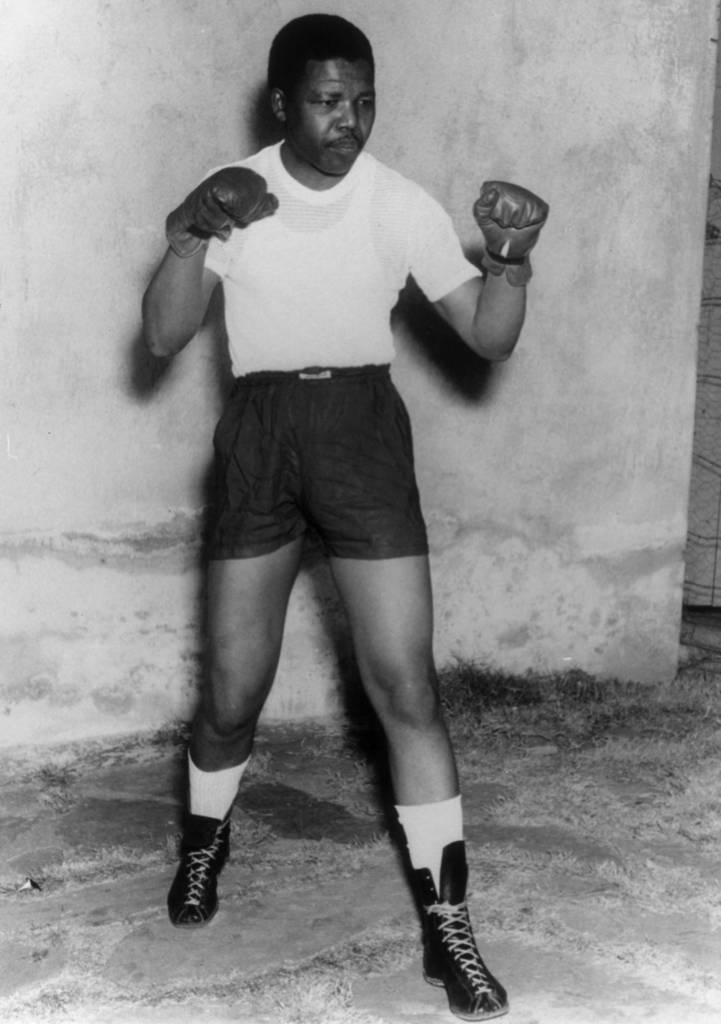

Some of the best people liked to box.

Nelson Mandela, leader of the African National Congress (ANC), adopts a boxing pose, wearing shorts, t-shirt and boxing gloves, circa 1950. (Photo by Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

It also attracted rougher elements.

Amateur boxers Reggie (left) and Ronnie Kray with their mother Violet Kray. The Krays went on to become notorious London gangsters. (Photo by Fox Photos/Getty Images)

What was it about twins and boxing? Have their been studies?

British boxer Henry Cooper (1934 – 2011, right) with his twin brother George (1934 – 2010), and their mother Lily at their home in Bellingham, south London, 13th January 1959. Henry is injured after his previous night’s fight against Brian London, in which he won the Commonwealth (British Empire) heavyweight title. George boxed using the name Jim Cooper. (Photo by Reg Speller/Fox Photos/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

The stars came to see and be seen at the bouts.

25th January 1950: American actor Gregory Peck (1916 – 2003) and his first wife Greta attend a boxing match between Freddie Mills and Joey Maxim at Earl’s Court, London. (Photo by Ron Gerelli/Express/Getty Images)

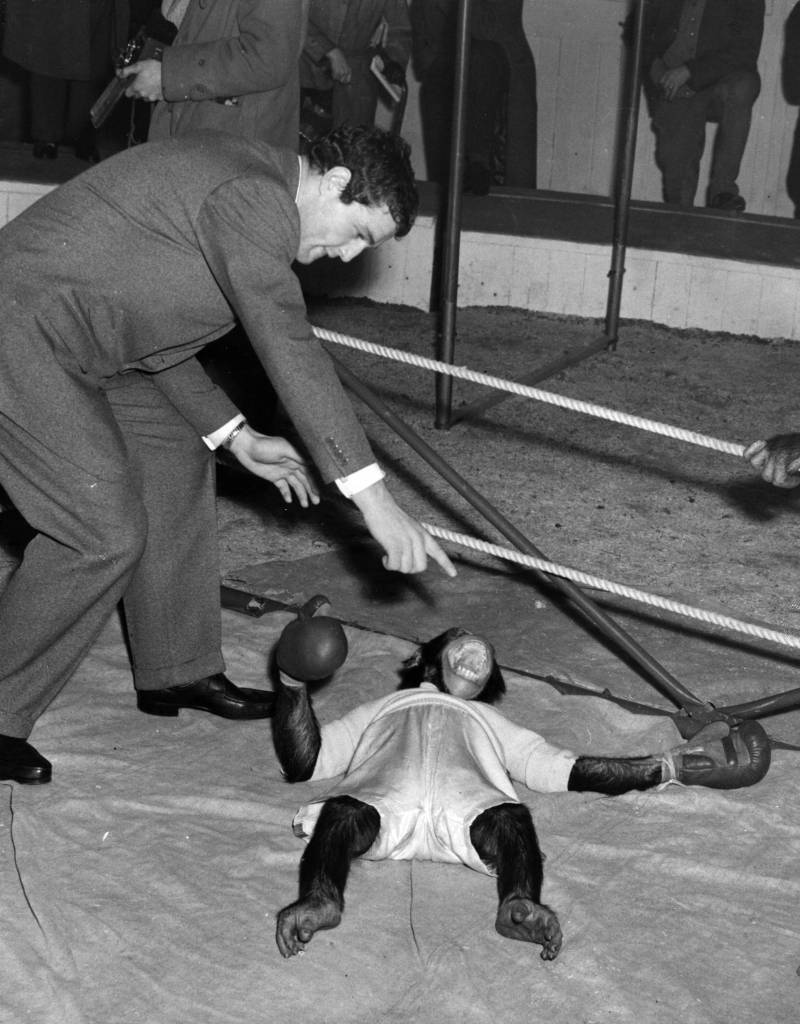

Anyone who wanted to could box. Well, not girls, obviously. They’re soft for the manly pursuits (see here, here, here and here.) But boxing chimpanzees were fine.

December 1955: Ron Barton the boxer counts out a chimp during the chimp boxing match being rehearsed at the Bertram Mills Winter quarters in Ascot. (Photo by Fox Photos/Getty Images)

Boys will be boys – and boys must not be girls.

June 1958: 12 year old John Ryder and his friend Trevor Briscoe play in a back garden in the coal mining area of Amthorpe, near Doncaster. Surprisingly, miner’s son John wants to be a ballet dancer and shows guts as well as ballet talent, fighting any local boys who call him ‘sissy’. He has also joined the school boxing team to prove it. (Photo by John Pratt/Keystone Features/Getty Images)

John Ryder’s father was a miner. John wanted to be a ballet dancer. Ridiculed and rubbished by his peers, derided as less than a real man by many, John took up boxing to prove that grace and power are not mutually exclusive.

In 2000, film fans flocked to see Billy Elliot, Lee Hall’s story of the son of a coal miner who dreams of becoming a ballet dancer. Billy’s dad sends him to the gym to learn boxing. Any similarities between events in the movie and real life and purely coincidental. Really.

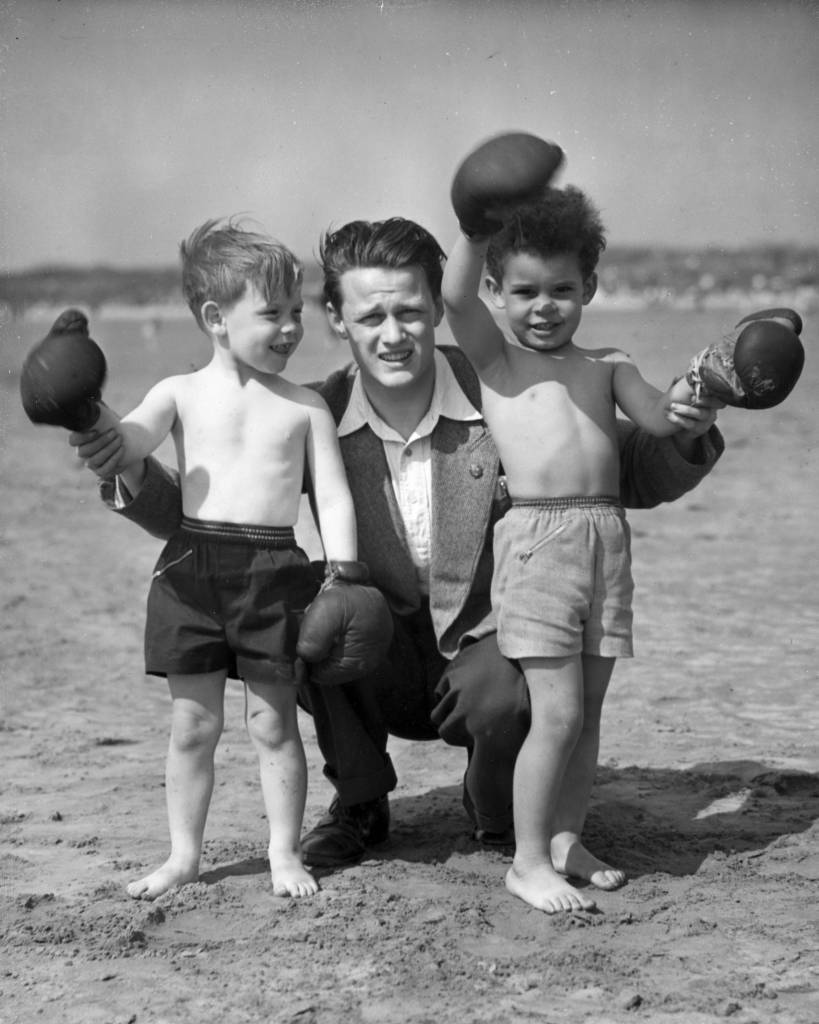

12th July 1954: Chris Davies, leader of the United Nations Boys’ Club in Wirral, Merseyside, gives young Billy Feston (left) and Paul Wilson a boxing lesson on the beach. The club aims to give boys from the inner city an opportunity to experience life in a rural holiday camp. (Photo by Kenny Rhodes/Fox Photos/Getty Images)

Let’s bring back boxing in schools.

Someone should have a word with the adults: the kids are alright.

Box on!

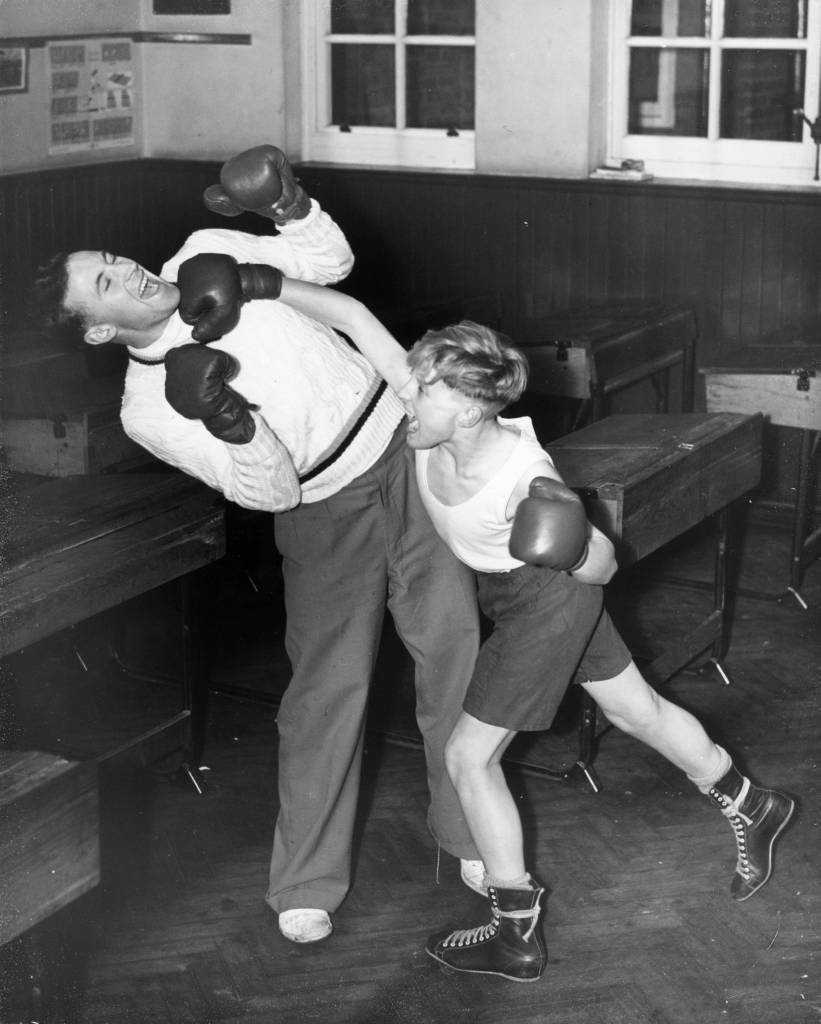

3rd December 1953: Christopher Miles, aged 14, having an after school boxing lesson with one of his teachers at Stepgate School in Chertsey. (Photo by Grierson/Fox Photos/Getty Images)

10th March 1954: Four young boxers practice their shadow boxing in front of a large mirror at a Dundee gymnasium. (Photo by Central Press/Getty Images)

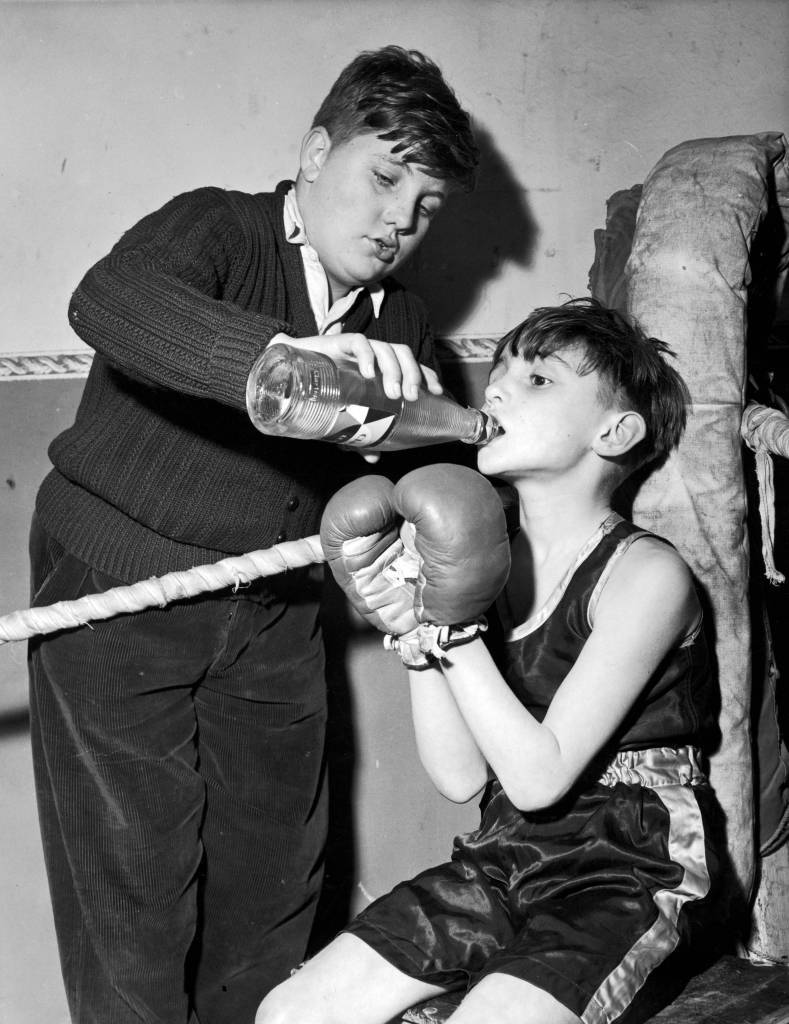

8th February 1956: Eight year old Tony Kelly having a drink between rounds, with the help of his second Brian King, at the Leyton Boxing Club. (Photo by Derek Berwin/Fox Photos/Getty Images)

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.