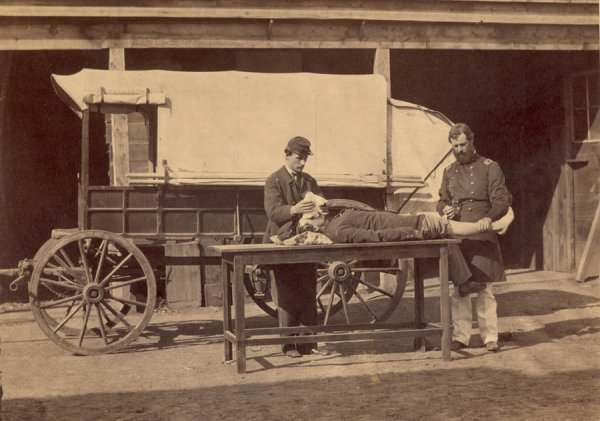

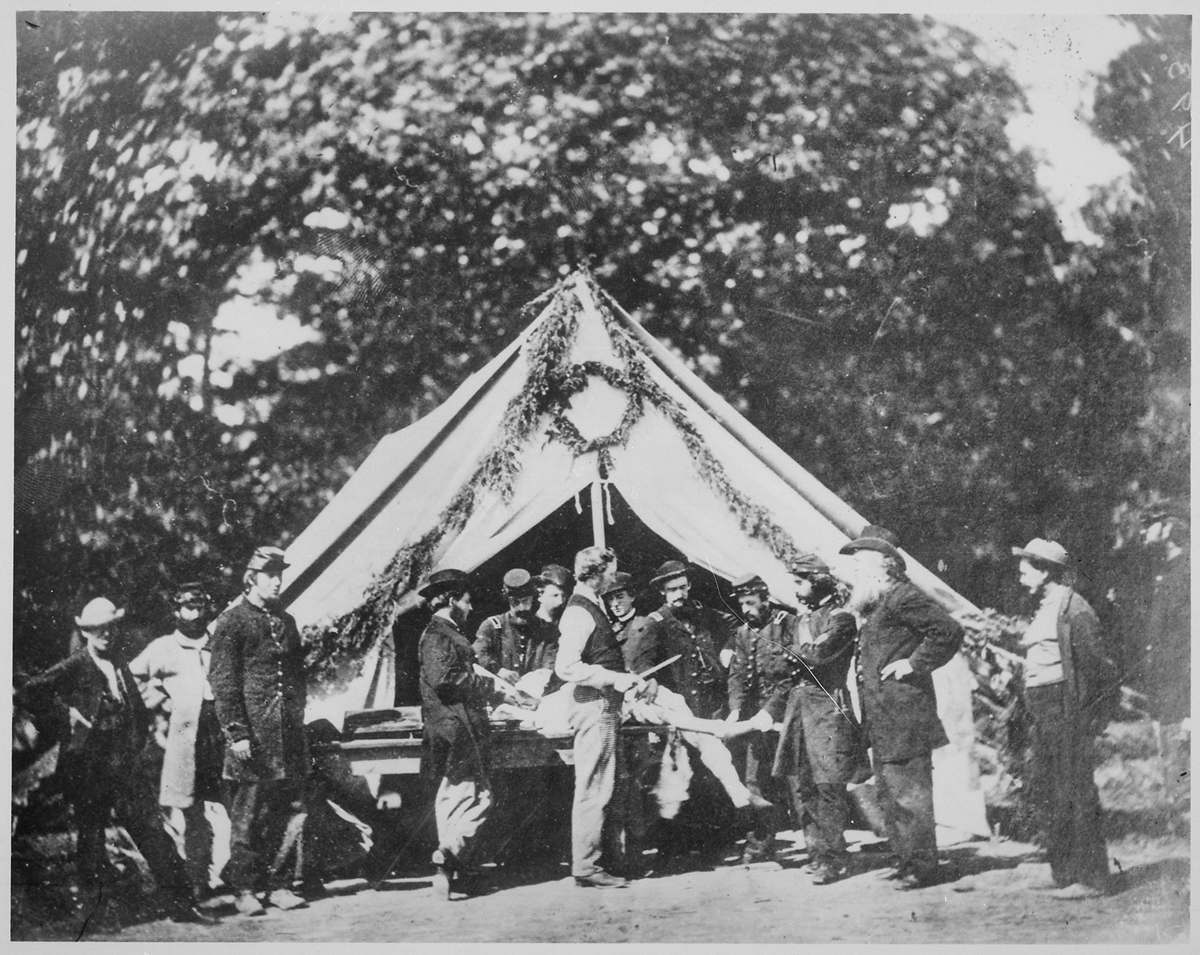

Army doctors performing an amputation in a make-shift hospital during the U.S. Civil War (1861-65), c. 1863. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

War is brutal. War is just. The American Civil War (1861–1865) was no exception. For many men that bloody war meant giving a limb for the cause. Amputations were the order of the day:

Amputation was the most common Civil War surgical procedure. Union surgeons performed approximately 30,000 compared to just over 16,000 by American surgeons in World War II.

Amputation being performed in front of a hospital tent, Gettysburg, July 1863

Courtesy National Archives and Records Administration

Terry L. Jones takes us to the scene of desperate butchery:

On Aug. 28, 1862, Maj. Gen. Richard S. Ewell’s Confederate division was fighting desperately in the fields and pine thickets near Groveton, Va., during the Second Bull Run campaign. Heavy fire was coming from unidentified soldiers in a thicket 100 yards in front. To get a better look, Ewell knelt on his left knee to peer under the limbs. Suddenly a 500-grain (about 1.1 ounces) lead Minié ball skimmed the ground and struck him on the left kneecap. Some nearby Alabama soldiers lay down their muskets and hurried over to carry him from the field, but the fiery Ewell barked: “Put me down, and give them hell! I’m no better than any other wounded soldier, to stay on the field.”

The general lay on a pile of rocks while two badly wounded soldiers nearby cried out for help until stretcher bearers finally arrived on the scene. Despite their own painful wounds, the two men insisted Ewell be carried off first, but he instructed the litter bearers to take them away. Hours after being wounded, Ewell was finally placed on a stretcher and taken to the rear. Dr. Hunter McGuire, Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson’s medical director, amputated Ewell’s leg the next day.

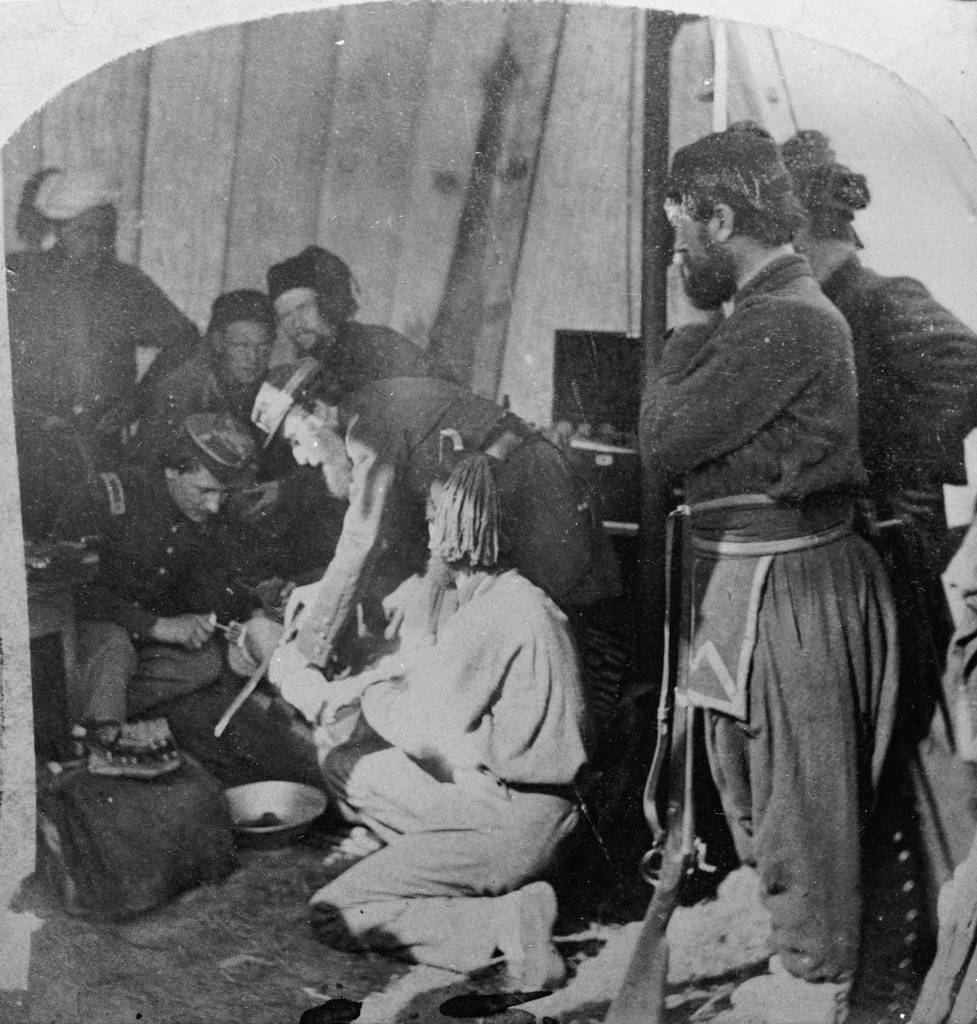

Campbell Brown, Ewell’s aide and future stepson, witnessed the operation. McGuire and his assistants sedated Ewell with chloroform and used a scalpel to cut around his leg just above the knee. In his drug-induced fog, Ewell feverishly issued orders to troops, but he did not appear to feel any pain until McGuire applied the bone saw. According to Brown, the general then “stretched both arms upward & said: ‘Oh! My God!’”

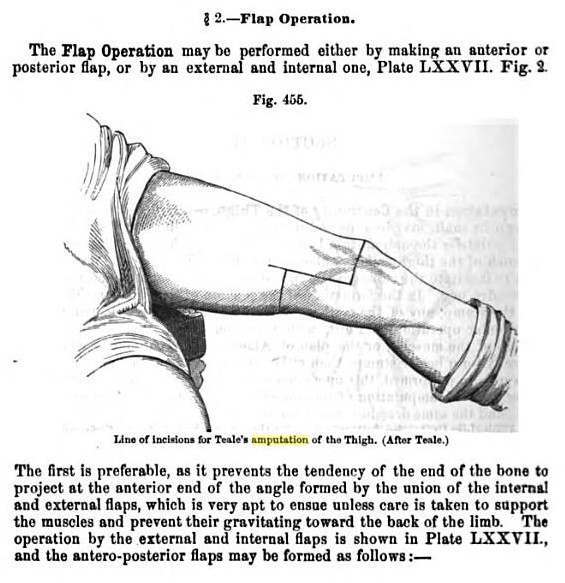

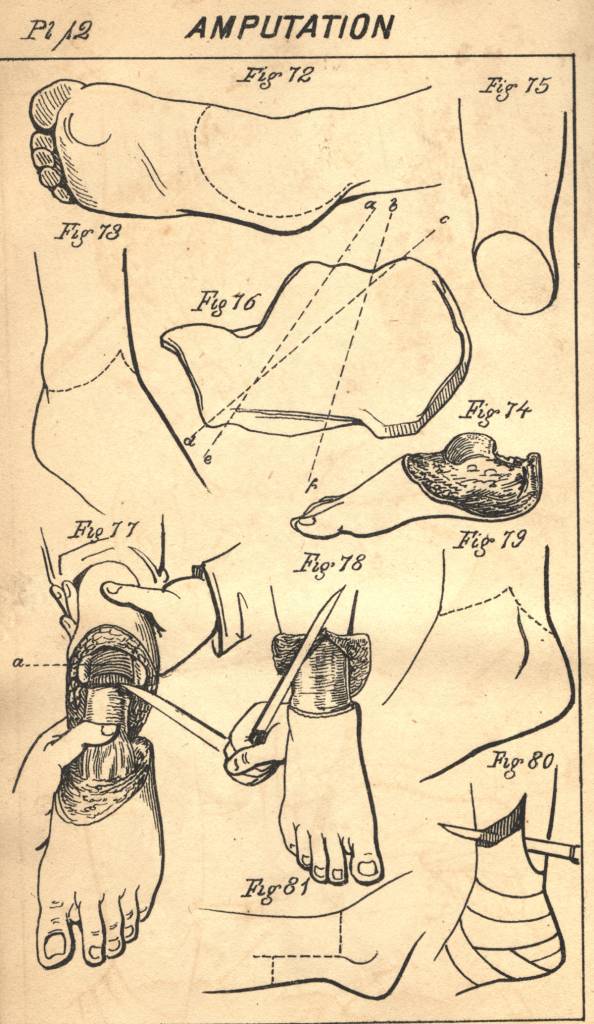

A Manual of Military Surgery, Confederate States of America, Surgeon General’s Office, 1863

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

The technique:

There were 2 main methods used to amputate large limbs during the War: Flap and Circular Amputations. In the field the flap method was more widely used where time was a factor. With this method the bone was dissected and flaps of deep muscle and skin were used to close the operation. When implementing the flap method it was imperative to cut the bone away a few inches above the place where the flaps were brought together.

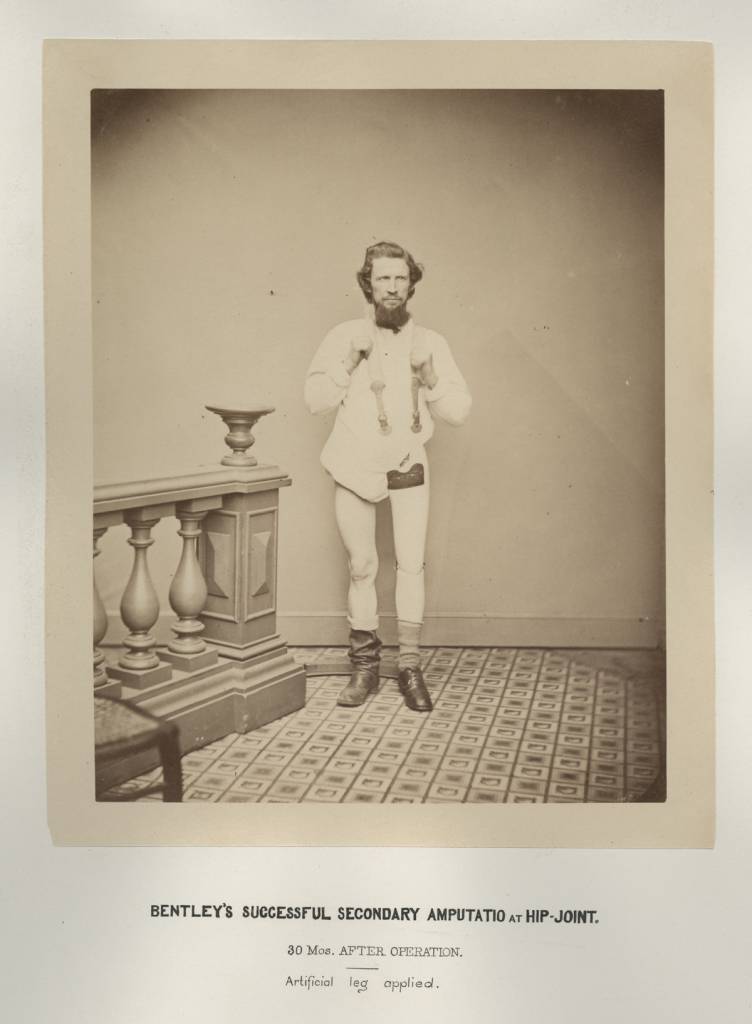

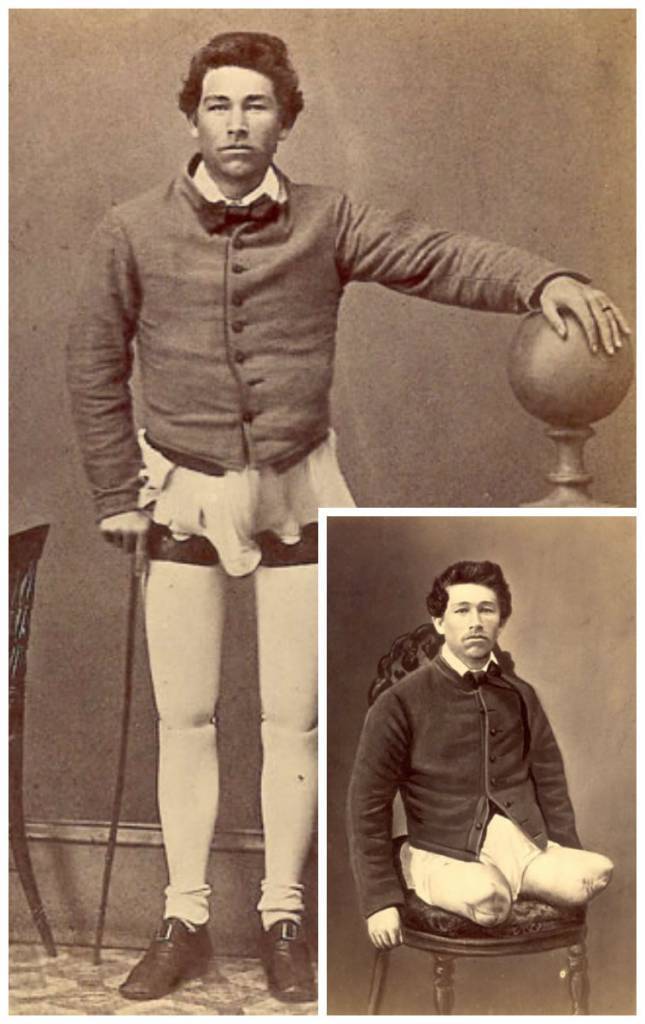

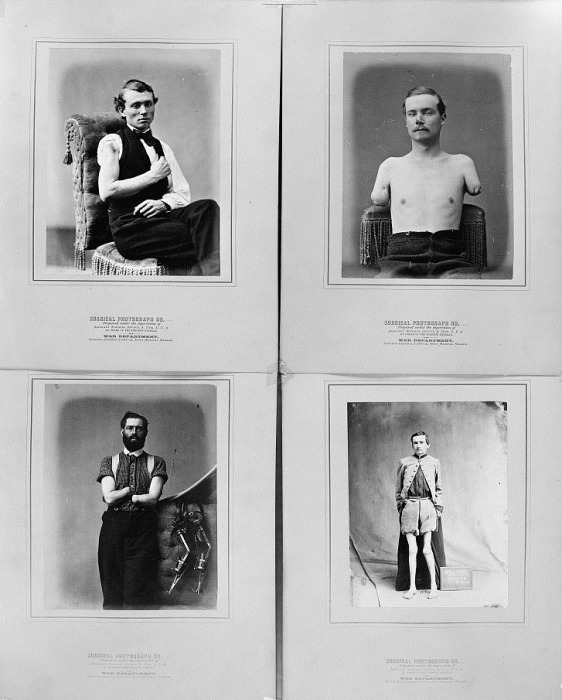

This series of photographs, compiled by the U.S. Surgeon General’s Office, illustrates the different types of arm amputations.

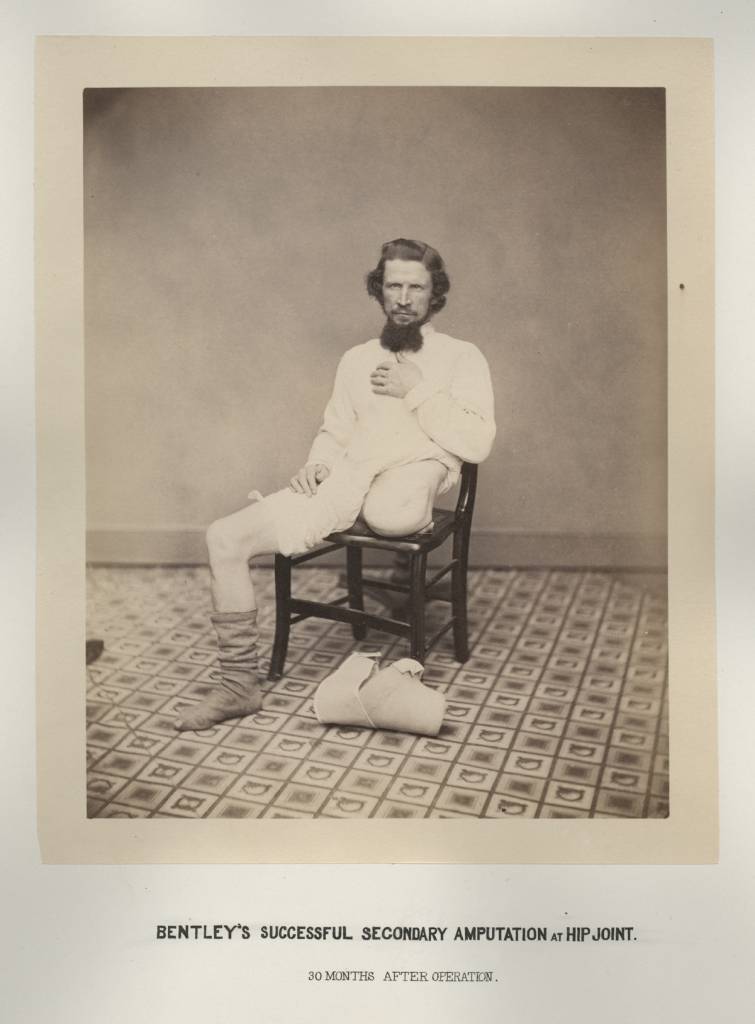

Private George W. Lemon, from George A. Otis, Drawings, Photographs and Lithographs Illustrating the Histories of Seven Survivors of the Operation of Amputation at the Hipjoint, During the War of the Rebellion, Together with Abstracts of these Seven Successful Cases, 1867

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

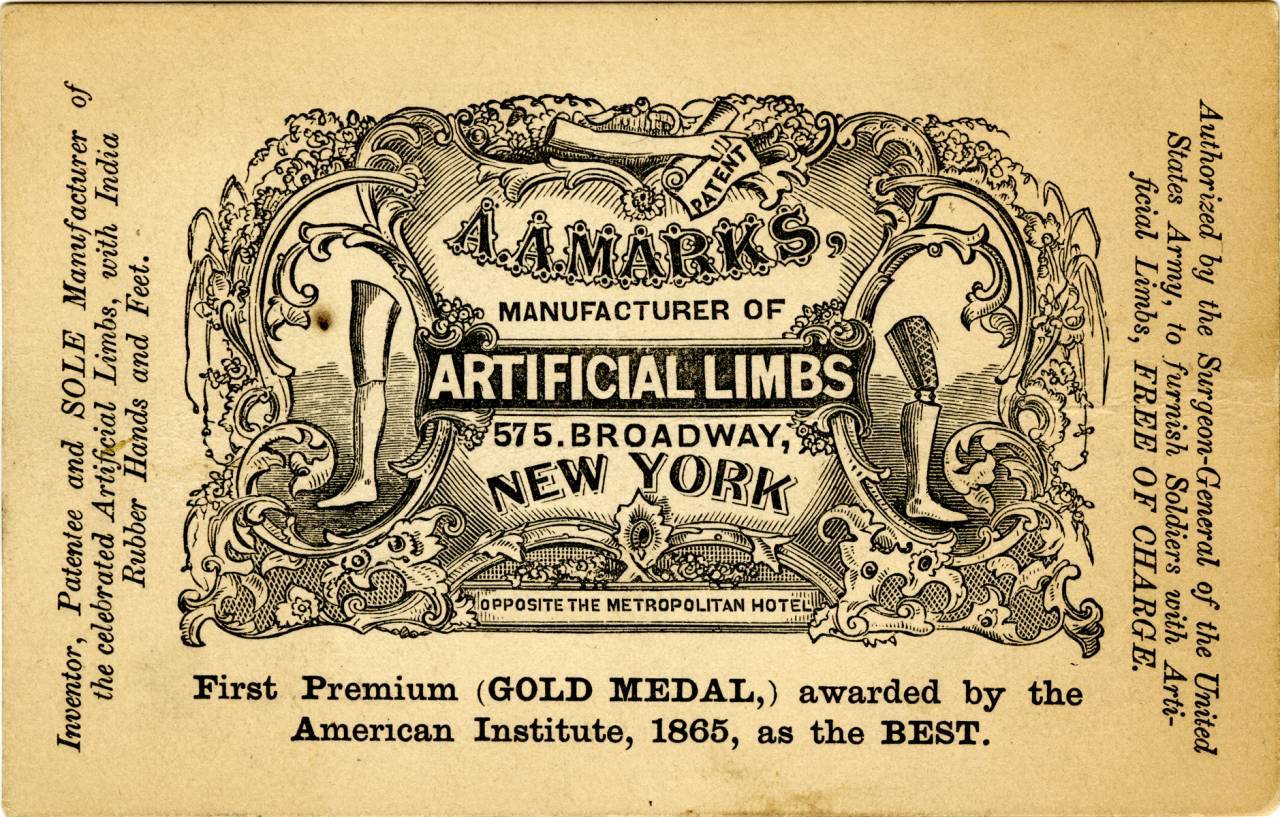

Reverse of A. A. Marks advertising card, late 1800s

Courtesy Warshaw Collection, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution

Amputations were good for the false limb business, as NCpedia notes:

North Carolina responded quickly to the needs of its citizens. It became the first of the former Confederate states to offer artificial limbs to amputees. The General Assembly passed a resolution in February 1866 to provide artificial legs, or an equivalent sum of money (seventy dollars) to amputees who could not use them. Because artificial arms were not considered very functional, the state did not offer them, or equivalent money (fifty dollars), until 1867. While North Carolina operated its artificial limbs program, 1,550 Confederate veterans contacted the government for help.

One Tar Heel veteran, Robert Alexander Hanna, had enlisted in the Confederate army on July 1, 1861. Two years later at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, Hanna suffered wounds in the head and the left leg, just above the ankle joint. He suffered for about a month, with the wound oozing pus, before an amputation was done. After the war, Hanna received a wooden Jewett’s Patent Leg from the state in January 1867. According to family members, he saved that leg for special occasions, having made other artificial limbs to help him do his farmwork. (One homemade leg had a bull’s hoof for a foot!) The special care helped the Jewett’s Patent Leg last. When Hanna died in 1917 at about eighty-five years old, he had had the artificial leg for fifty years. It is a remarkable artifact—the only state-issued artificial leg on display today in North Carolina. Hanna’s wooden leg, as well as Civil War surgical equipment, may be seen at Bentonville Battlefield State Historic Site in Four Oaks.

Many did not want a false limb.

A large proportion of disabled veterans in both the North and the South did not wear artificial limbs. Many did not even apply for the money they were eligible to collect because of negative attitudes to the idea of charity. Moreover, pinning up an empty sleeve or trouser leg, instead of hiding the injury with a prosthesis, made their sacrifice visible. Displaying an “honorable scar” in this way, especially during and immediately after the war, helped amputees to assert their contribution to the cause.

Veterans who had lost an arm learned to use their remaining limb instead, and could utilize specially-designed devices to tackle everyday tasks. Such strategies were especially important because many prosthetic designs had only limited function and could also be uncomfortable, particularly if the wounds from injury or surgery had healed badly. Moreover, an artificial limb might prove too expensive to repair or replace over the course of a lifetime.

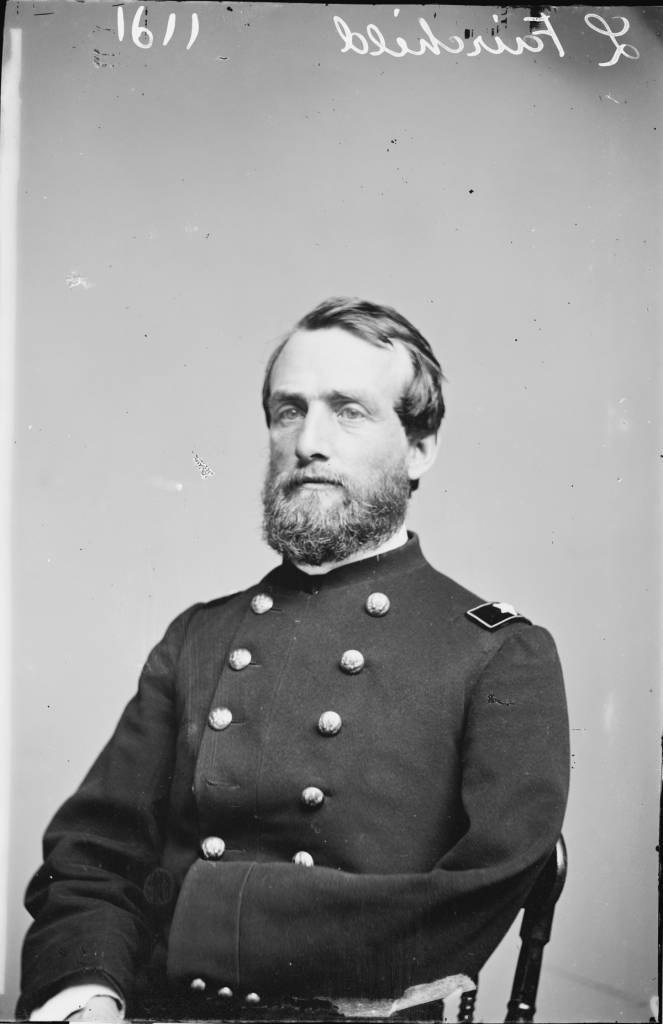

Lucius Fairchild lost his left arm on the first day of the Battle of Gettysburg in 1863. He was elected Governor of Wisconsin in 1866.

Courtesy Library of Congress

Major General Daniel E. Sickles and leg – National Medical Musuem

Major General Daniel E. Sickles (above), Union Third Army Corps commander, was struck by a cannonball during the battle of Gettysburg.

Sickles was on horseback when the 12-pound ball severely fractured his lower right leg. Sickles quieted his horse, dismounted, and was taken to a shelter where Surgeon Thomas Sims amputated the leg just above the knee. Shortly after the operation, the Army Medical Museum received Sickles’ leg in a small box bearing a visiting card with the message “With the compliments of Major General D.E.S.” The amputation healed rapidly and by September of 1863 Sickles returned to military service. For many years on the anniversary of the amputation, Sickles visited his leg at the museum.

Sickles was photographed in 1865 at the Army Medical Museum. William Bell. Woodward 1760. Sickles’ exploits extended beyond the Civil War. He was the first defendant to successfully use the temporary insanity defense in the United States. In 1859, Sickles was found not guilty of the murder of his wife’s lover, Philip Barton Key, the son of the composer of the national anthem. Sickles had shot Key in Lafayette Square in Washington in a jealous rage after learning of the affair. Sickles served as a secret agent for President Lincoln and was appointed Ambassador to Spain by President Grant.

Francis R. T. Nichols lost an arm and a foot in separate Civil War battles. He became Governor of Louisiana in 1877.

Courtesy Library of Congress

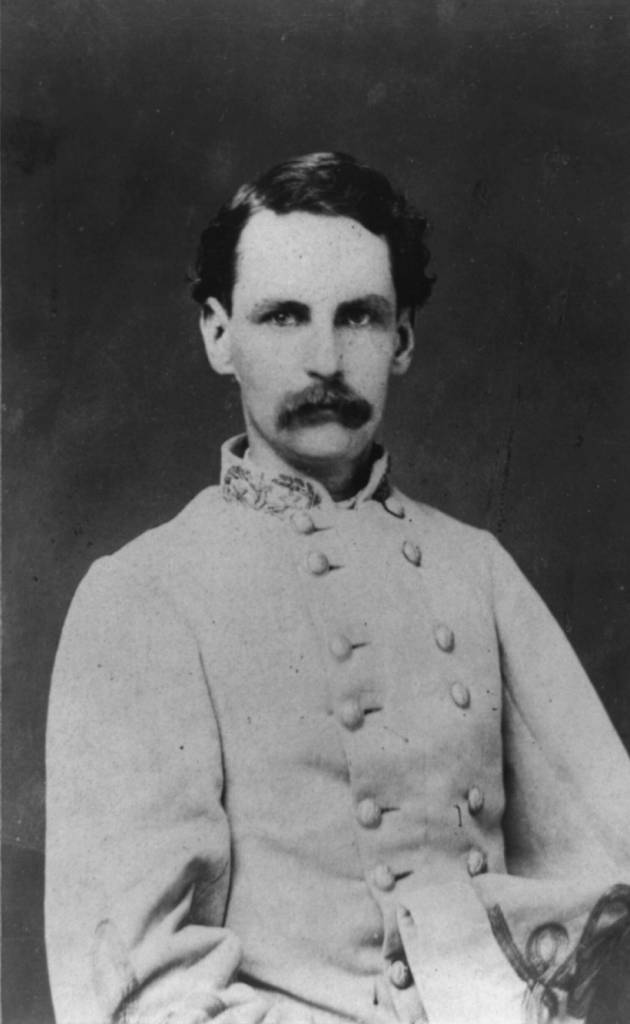

Veterans John J. Long, Walter H. French, E. P. Robinson, and an unidentified companion, 1860s

Courtesy Library of Congress

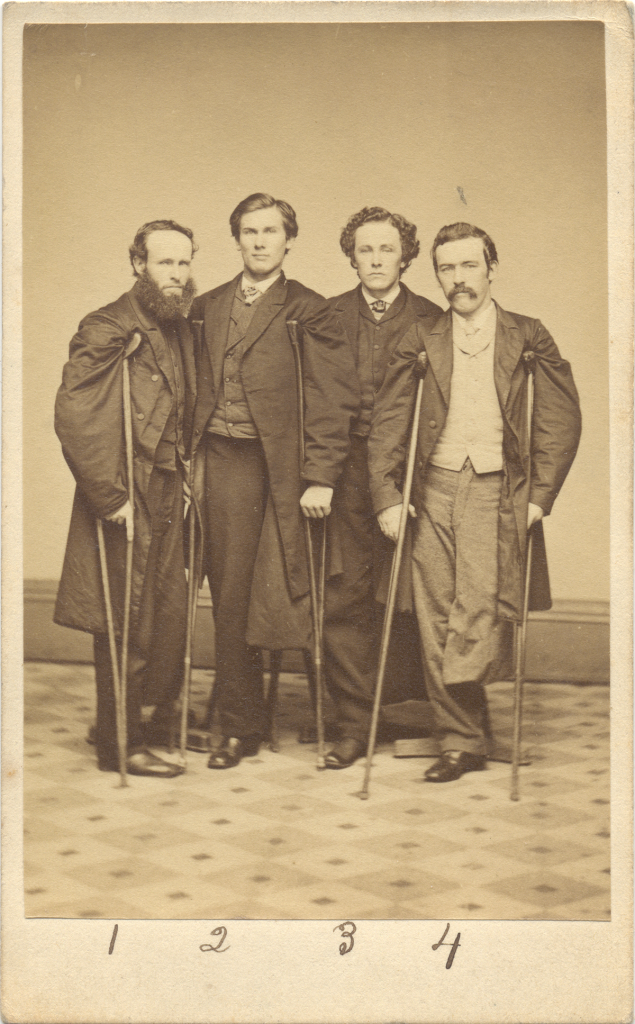

Private Columbus Rush, Company C, 21st Georgia (above), age 22, was wounded during the assault on Fort Stedman, Virginia, on March 25, 1865 by a shell fragment that fractured both the right leg below the knee and the left kneecap. Both limbs were amputated above the knees on the same day. He recovered quickly and was discharged from Lincoln Hospital in Washington on Aug. 2, 1865. In 1866, while being treated at St. Luke’s Hospital in New York City, he was outfitted with artificial limbs.

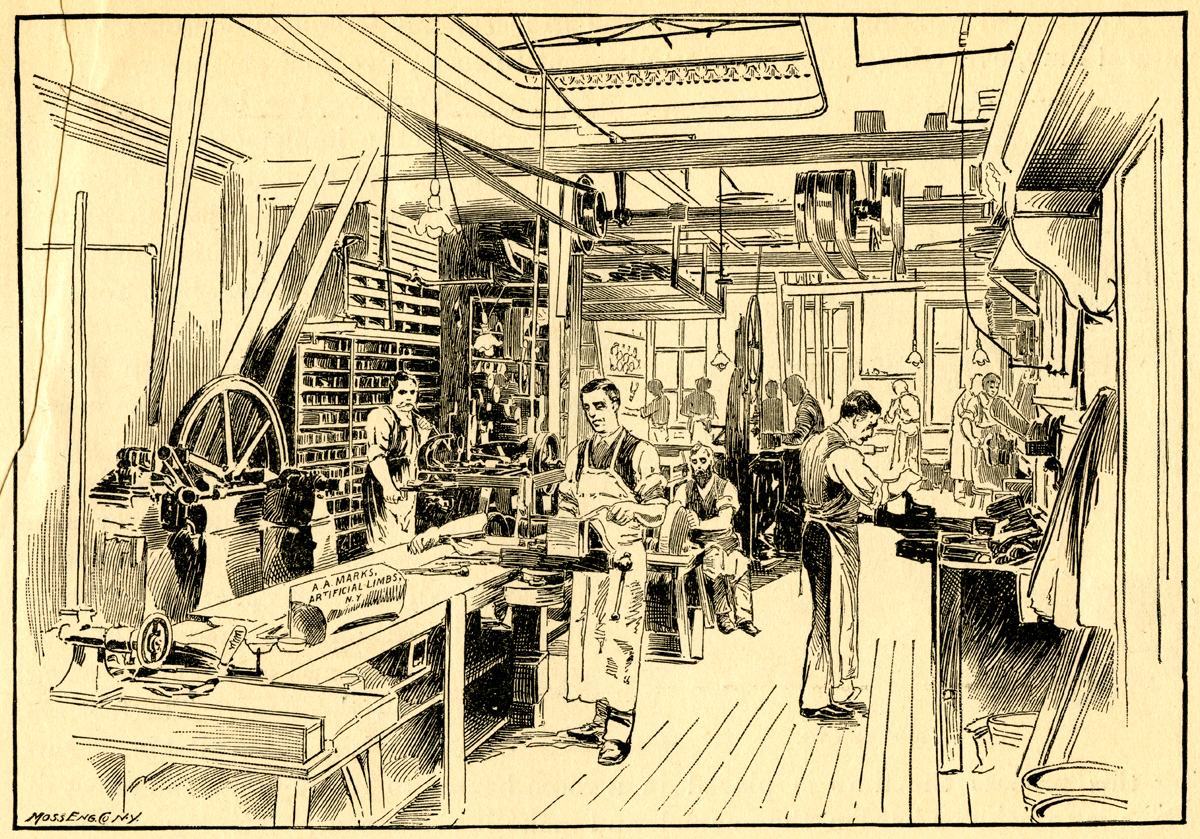

“From Stump to Limb,” on the making of prosthetics, by the manufacturer A. A. Marks, late 1800s

Courtesy Warshaw Collection, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution

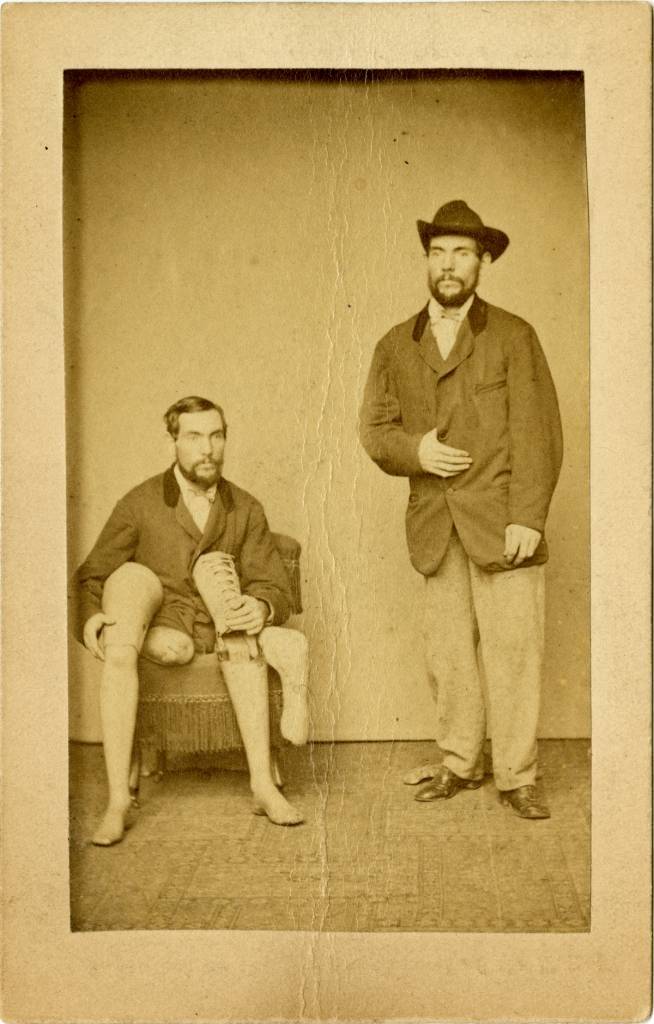

A. A. Marks advertising card, showing a customer holding and wearing his artificial legs, late 1800s

Courtesy Warshaw Collection, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution

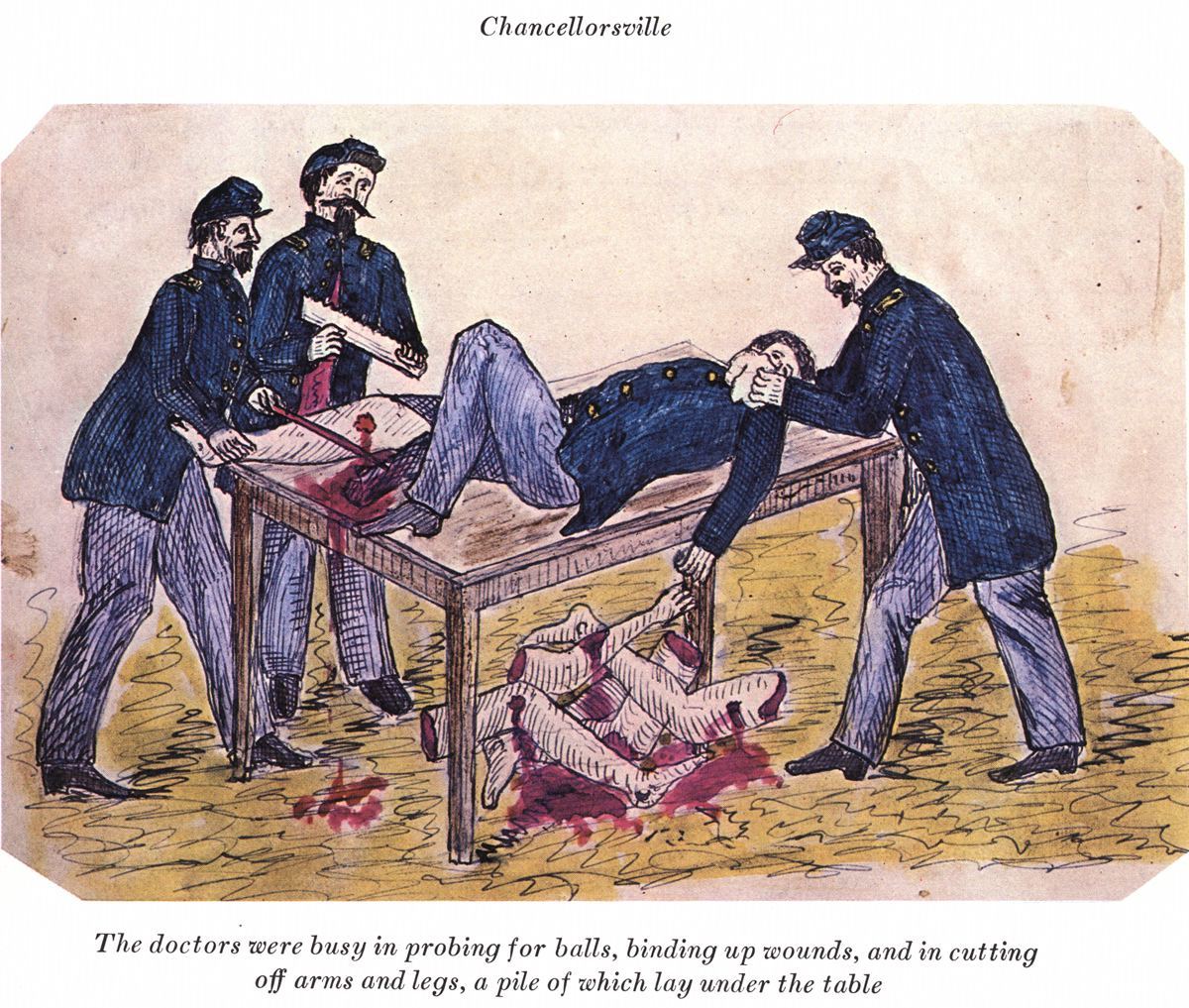

“The doctors were busy in probing for balls, binding up wounds, and in cutting off arms and legs, a pile of which lay under the table”, drawings from the diary of Alfred Bellard, 1860s

Courtesy Alec Thomas Archives

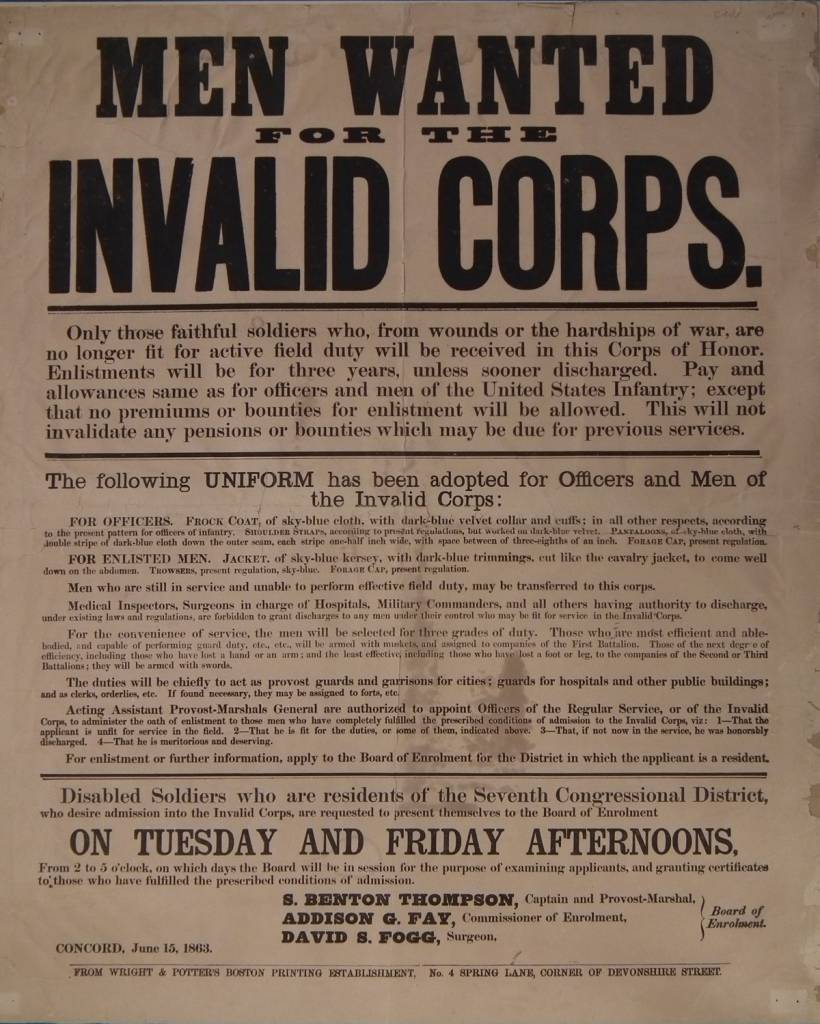

US National Library of Medicine write that some injurded soldiers stayed in the military:

The Invalid Corps was established by the federal government in 1863 to employ disabled veterans in war-related work. Soldiers were divided up into two battalions, based on the extent of their injuries. The first carried weapons and fought in combat.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.