Millions of Baby Boomers have been seized by the same disorienting flashback, in which they’ll be hurtled through time and space to San Francisco in 1967, at the height of the Summer of Love. The trigger will lurk in the coverage of this alleged cultural watershed by news organizations, magazines, and websites tripping over themselves to celebrate the 50th anniversary of what was, in fact, a marketing gimmick designed to capitalize on a scene that was already dead. To avoid taking this bummer of a trip, steer clear of images of doe-eyed young people dressed in their Goodwill finest, blowing soap bubbles and smoking doobies in Golden Pate Park while flashing the peace sign beneath beatific halos of flowers and feathers braided into their long, flowing hair.

“I heard that a band called Big Brother and the Holding Company was playing at a place on Fillmore, so I went.”

Here’s the thing, though, that you might not know about the Summer of Love. Turns out that some of those utopian flower children were actually working pretty darned hard at the dawning of the Age of Aquarius. In particular, the bands that gave the psychedelic scene its soundtrack knew what it meant to earn a buck. Take Country Joe and the Fish: In 1967, the quintet played roughly 140 gigs. Jefferson Airplane’s workload was just about the same, while the Grateful Dead logged almost 120 shows. Not bad for a bunch of hippies stoned to the gills on LSD.

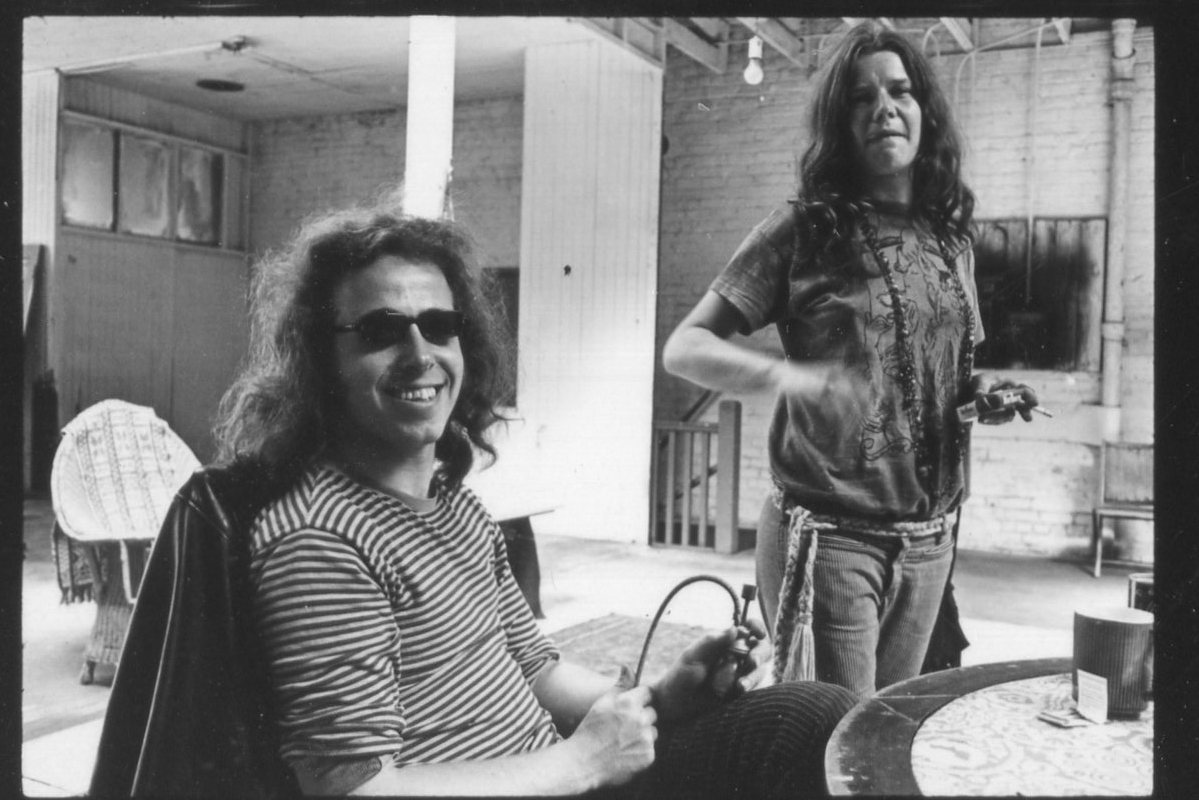

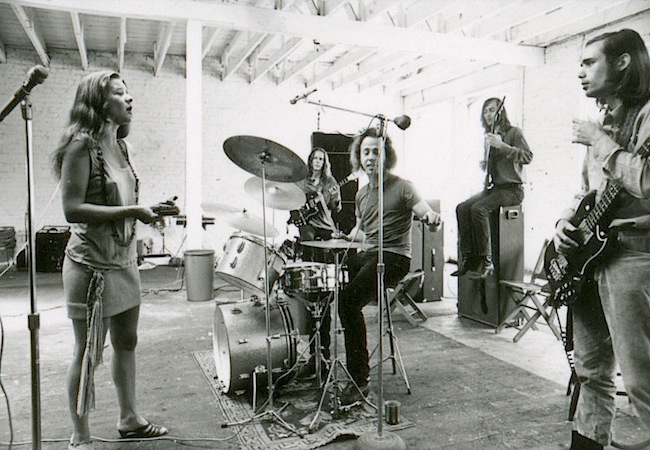

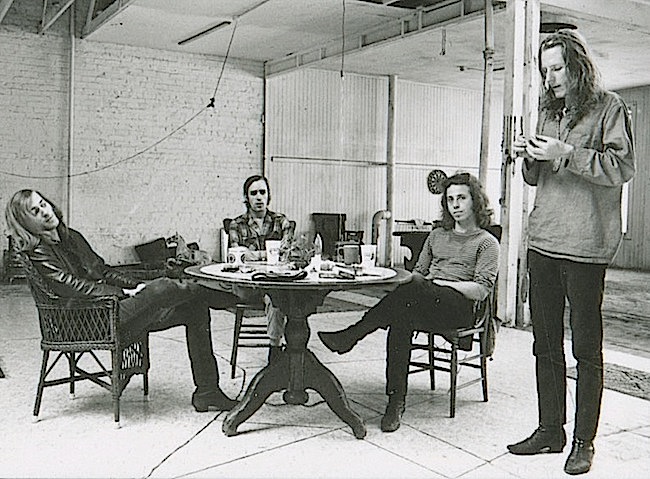

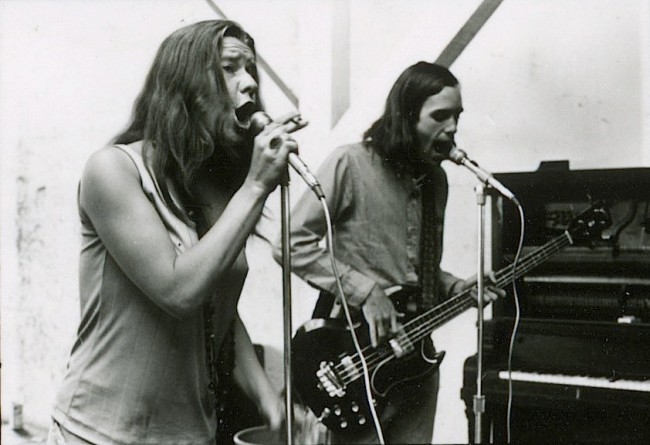

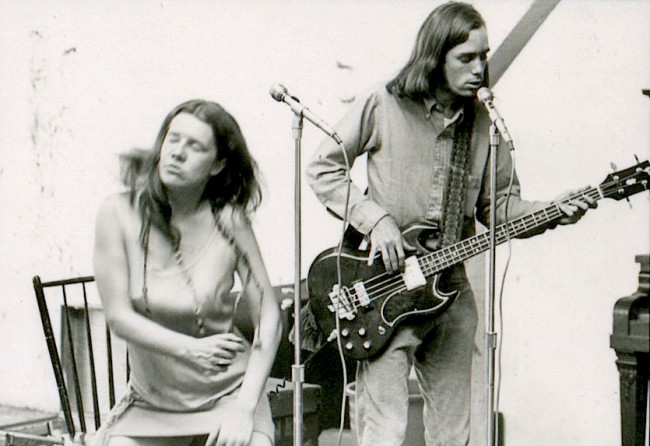

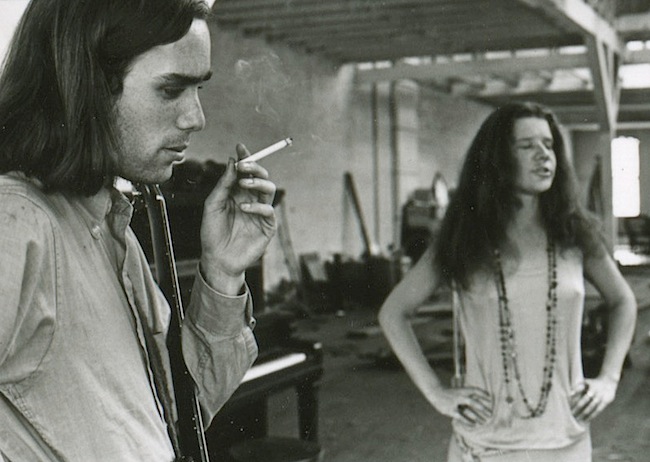

Foremost among these hardworking musicians were the members of Big Brother and the Holding Company, which performed 135 concerts during 1967, occasionally grinding out two or three gigs in a single day. We know this from the unofficial historical record, but also from the photographs taken by the band’s unofficial photographer, Bob Seidemann—many of his candid shots of Big Brother rehearsing in their warehouse on Golden Gate and Van Ness avenues in San Francisco are being published here for the very first time.

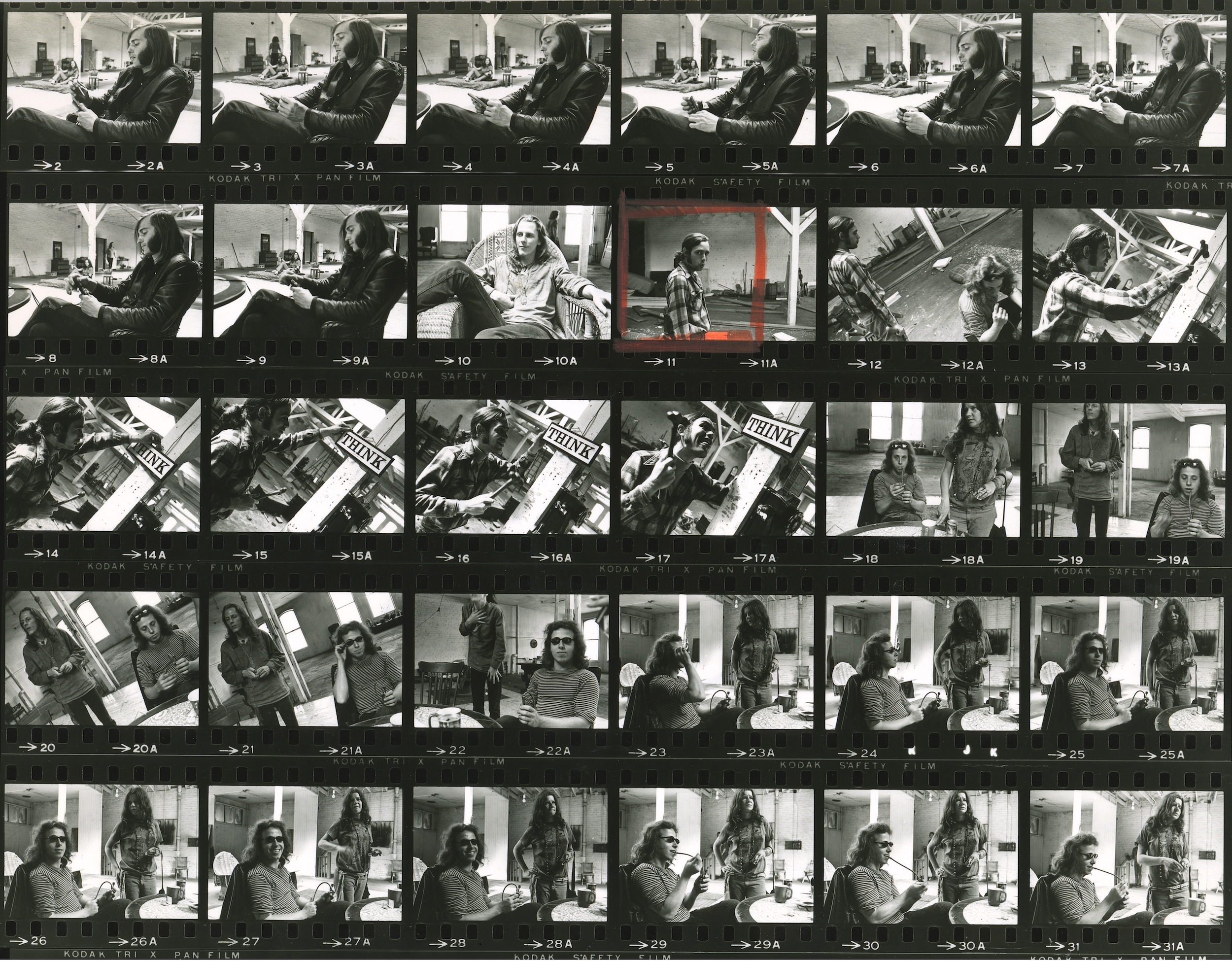

One of dozens of proof sheets of black-and-white photographs taken by the band’s friend and resident photographer, Bob Seidemann.

Seidemann would go on to become one of the premier rock photographers of the 1960s and ’70s, creating album covers for Jerry Garcia, Blind Faith, Jackson Browne, and Neil Young. But when he was a part of the extended Big Brother family, Seidemann did most of his work off the clock, snapping his shutter when the mood struck rather than when he had an assignment from a magazine or record company. As a result, Seidemann’s photos of the band during its brief heyday, 1966 through 1968, are a uniquely intimate and complete portfolio, produced at a moment in history when the notion of posterity was not exactly at the forefront of most people’s minds.

“I wasn’t trying to be a documentarian,” Seidemann told me when we spoke recently about his relationship with Big Brother. “I was just hanging out, you know? I was a friend of these people. As their work progressed, so did mine.”

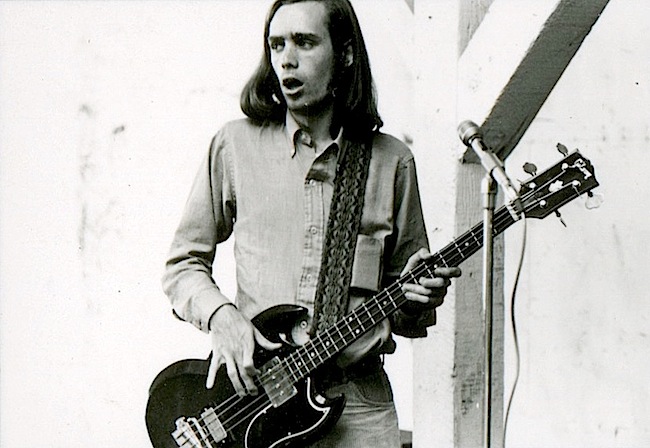

That’s how Big Brother co-founder and bassist, Peter Albin, remembers it, too. “Bob was just always around,” Albin says. “He wasn’t like Jim Marshall, who had a camera with him all the time. Bob was a friend. Sometimes he had his camera; sometimes he didn’t.”

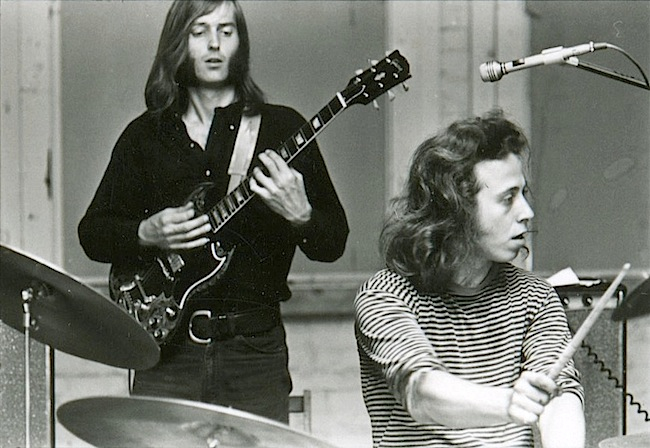

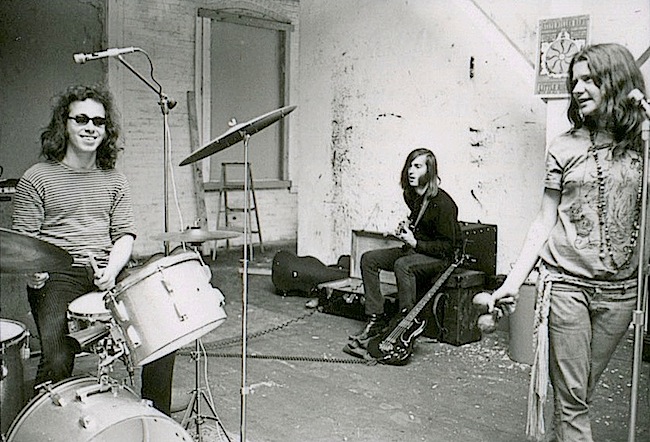

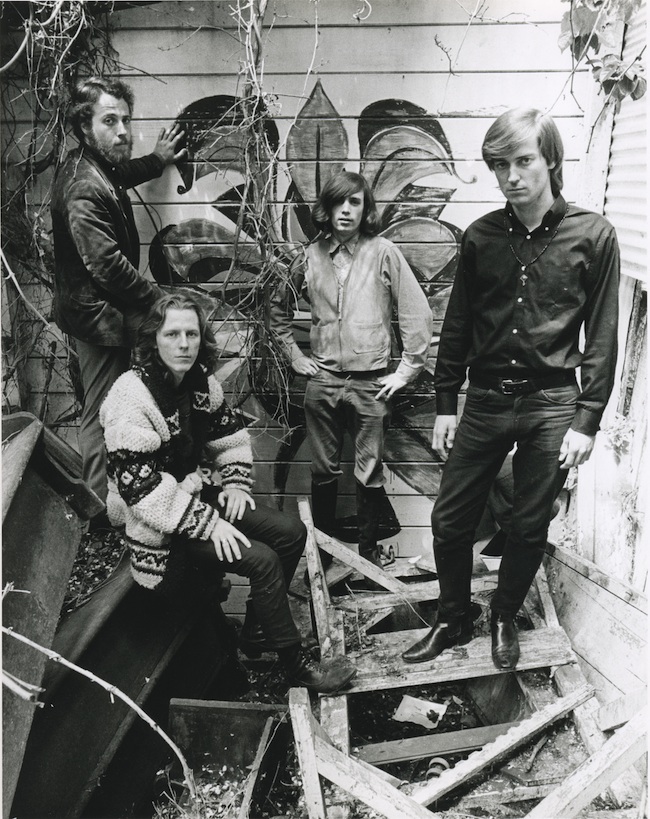

Big Brother and the Holding Company in the spring of 1966 behind the Old Spaghetti Factory, where drummer Dave Getz (far left) worked part time

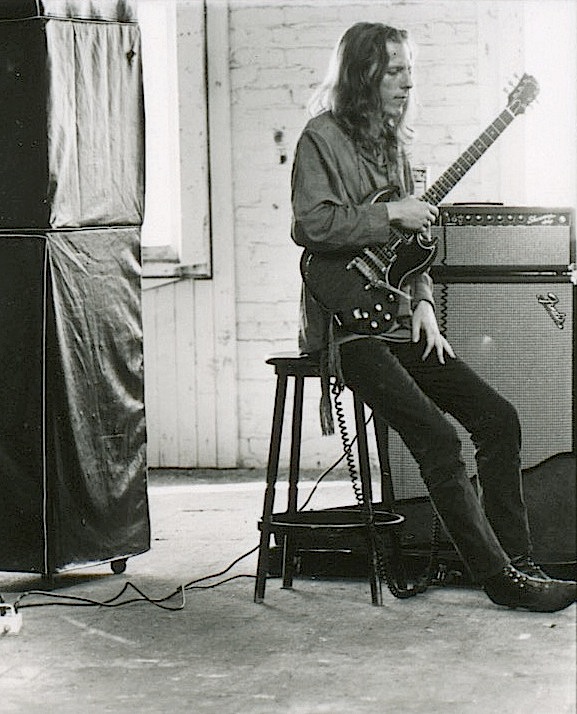

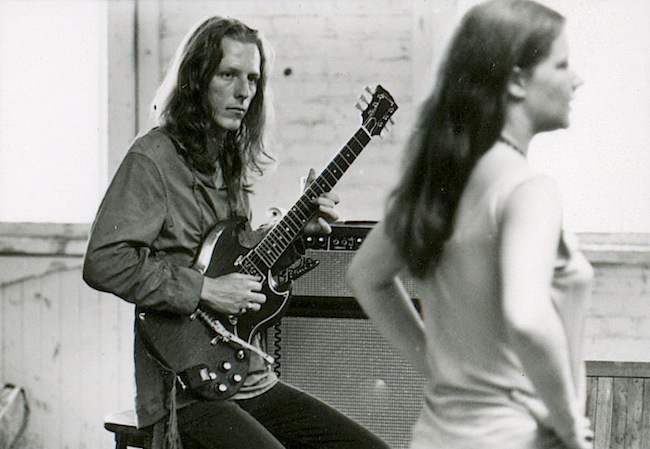

Before Janis Joplin jined the group in June 1966, lead guitarist James Gurley has been the group’s most popular member

The seeds of Seidemann’s relationship with Big Brother were planted in 1963, when the New York native, fresh out of high school, moved to San Francisco. Seidemann had been lured west by the hepcat-cool jazz scene in the city’s bohemian-leaning North Beach neighborhood. But after returning to New York for a year or so, and then hightailing it back to San Francisco sometime in late 1965 or early 1966, the aspiring beatnik found himself in a sea of hippies.

That was actually just fine with Seidemann. “I was putting the pieces of my life together,” he says about those early days. “One day, I heard that a band called Big Brother and the Holding Company was playing at a place on Fillmore, so I went.”

The “place” was a small club called the Matrix, which hosted the band for a week, from March 1 to March 6, 1966. At the time, Big Brother consisted of guitarists James Gurley and Sam Andrew, bass player Peter Albin, and a drummer—Fritz Kasten began that Matrix run, Norman Mayell finished it, and a few days later Dave Getz joined the band, bringing the game of musical chairs behind the drums to an end.

The arrival of Janis Joplin, who would become Big Brother’s lead singer and the most acclaimed female rock star of the late 1960s, was still a few months away.

Today, most people who have heard of Big Brother and the Holding Company assume it started out as Janis Joplin’s backup band. In fact, by the time Joplin took the stage with the rest of Big Brother at the Avalon Ballroom on June 24, 1966, Albin and Andrew had been playing with other musicians as Big Brother and the Holding Company since September of the previous year. James Gurley joined the band in November of 1965 and Dave Getz followed in March of 1966.

“I wasn’t trying to be a documentarian. I was just hanging out.”

During those crucible days, Big Brother was big on experimentation. According to James Gurley, who was interviewed before his death in 2009 for Living With the Myth of Janis Joplin: The History of Big Brother & the Holding Company, by Michael Spörke, the band’s early style was highly improvisational, with sets lasting an hour or two, unconstrained by setlists or even the verse-chorus structure of songs. “We were more like a jazz band at that point,” Gurley told Spörke.

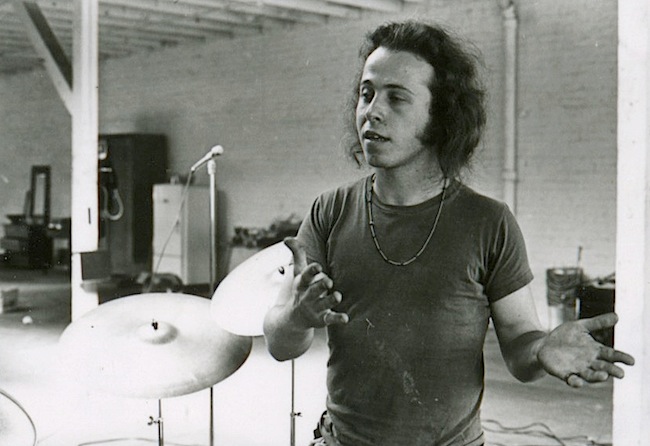

A fast and furious jazz band, that is. “Punk rock didn’t exist in those days,” Dave Getz told me, “but we were close to a punk-rock band in some ways. The energy of Big Brother was like, ‘Let’s play it as fast and as hard as we can.’ I used to break sticks, I used to break drum heads. I can’t imagine doing that now.”

Big Brother’s style, though, be it jazz or proto-punk, was not what drew Seidemann to this loud new world. “To be honest with you, I wasn’t all that interested in the music,” he says. “It was the scene, you know? Getting stoned, having a good time, and getting stoned again. I loved that milieu, so I sought out the musicians. Even though I didn’t play an instrument, I wound up in the middle of that whole crowd.”

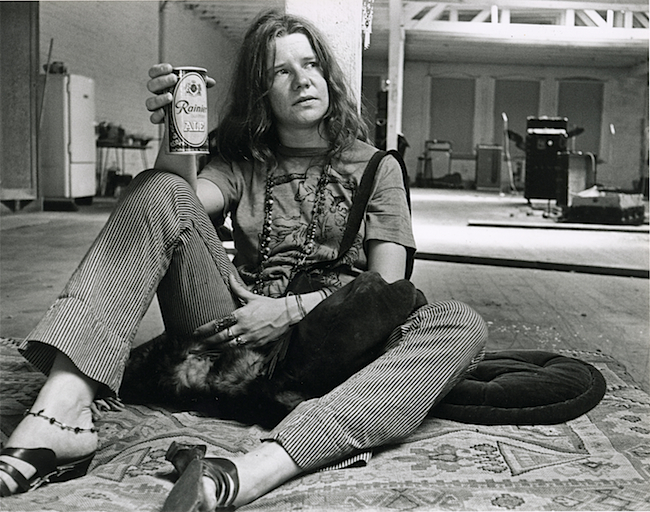

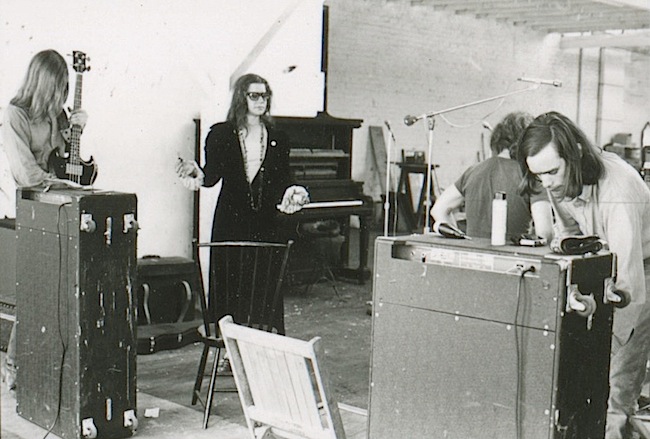

Janis Joplin arriving for a rehearsal at Big Brother’s warehouse at Golden Gate and Van Ness avenues in San Francisco

Dave Getz was the first member of the band Seidemann sought out, although their first encounter appears to have occurred a bit before Getz joined Big Brother. Neither man remembers the precise date, but they agree on the place. “I was working part time as a cook at the Old Spaghetti Factory in North Beach,” Getz tells me when we spoke over the phone. “The owner of the place was a guy named Freddie Kuh, who had the taste of a gay antiques collector on acid. The decor was on the far-out edge of camp—weird Greek statues, foppish paintings, stuff hanging from the ceiling, and mismatched furniture collected in second-hand shops, all thrown together. It was great, in its own strange way.”

“The energy of Big Brother was like, ‘Let’s play it as fast and as hard as we can.’”

Secreted within this old-world, somewhat surreal, atmosphere was a table in the kitchen, where Getz and assorted friends from the art world hung out. “I was a painter before I joined Big Brother,” Getz explains, “teaching two classes at the San Francisco Art Institute. Sometimes Bob would bring in a friend of his named ‘Hap’ Kliban, who was a cartoonist. ‘Hap’ would show us his latest cartoons with all these cats on them, and we’d have a laugh.”

More often than not, those laughs were lubricated by drugs. “LSD was an integral part of the scene in San Francisco in those days,” Seidemann says matter-of-factly. “I got mine from a guy on Bay Street. Everybody was getting smashed.”

Sometimes literally. “One night,” Getz says, “Bob was hanging around after I had finished cleaning up. We were talking, and I mentioned that I had some pharmaceutical LSD and asked him if he want to do some with me. So we took an acid trip together. We ended up getting in a huge car accident that night, which is a whole other story, but it was definitely a bonding moment. From that point on, through most of ’66 and ’67, we spent a lot of time together. We were very close in those days.”

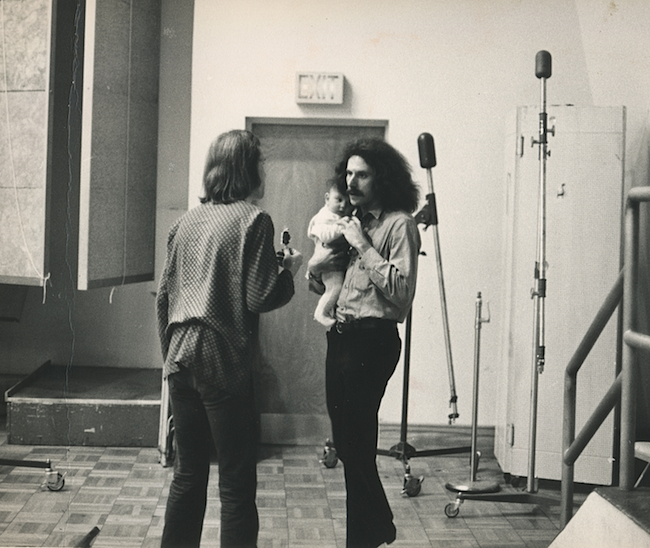

In a photo by Bob Cato, photographer Bob Seidemann is seen holding a band member’s baby while talking with Big Brother’s road manager, David Richards.

It was also at the Old Spaghetti Factory that Seidemann met Janis Joplin, probably in June of ’66. “One evening,” Seidemann remembers, “David Getz had someone with him. ‘This is our new chick singer,’ he announced. It was Janis Joplin. She looked like a rag that somebody had cleaned the windows with. She was a mess. We all looked at each other and said, ‘Well, give it a shot.’ That’s how we met her.”

Adding Janis Joplin to the all-male quartet was a major change for the band, as the late Sam Andrew told Spörke in Living With the Myth of Janis Joplin. “Big Brother’s music had been very experimental, free, and improvisatory up to this point, but now the band had a singer, and singers need to know when to begin singing … Gone were the days when James and I could just float freely over a theme in E minor and let the song take [us] where it would.”

By necessity, then, the style of the band’s music evolved, shifting from the rapid-fire pace propelled by James Gurley’s lightning-fast fingerpicking on lead guitar to a slower tempo better suited to Joplin’s love of the blues.

Working out all these changes made rehearsing more important than ever, which is why, in early 1967, the band rented the second floor of a building on the corner of Van Ness and Golden Gate. “We had this warehouse,” Getz says, “which is where Bob’s pictures were taken. It’s now called Opera Plaza, but at that time, it was in kind of a funky area. It was probably a couple of thousand square feet, a really a big space, with a garage and storage area downstairs.”

“It was in a redevelopment area,” Albin says. “The city wanted to tear the building down because it was in the way of a new extension of the freeway, which never happened. That’s how we got it.”

According to Getz, the advantage of a designated rehearsal space was that the band could leave its equipment set up, ready to go. “Pretty much whenever we weren’t doing a gig, we rehearsed. Being in Big Brother was just like having a full-time job. We’d usually meet in the afternoon, around 1:30 or 2, and then practice until 4, 5, or when everybody got hungry or wanted to get out of there.”

Despite the short duration of their rehearsals, it was work all the same, as Sam Andrew confirms in Living With the Myth of Janis Joplin. “It was, ‘OK, Peter, you will play three times around, then Dave will do this for two measures, and then I will come in on the third beat.’ This is what was heard at rehearsal now. The music became more purposeful and more directed.”

“We’d go over the setlists and find songs that we were having problems with, or ones we just wanted to change up a little bit,” Albin adds.

The warehouse, as the band called it, was a good place to do this sort of polishing since it was both casual and private. “I don’t remember many people coming there,” Getz says. “Bob was there a lot, of course, plus a few really close friends. It wasn’t like some kind of open thing where people would show up and sit around and watch a rehearsal. It wasn’t like that at all. I don’t remember more than a couple of people being there during rehearsal. Most times it was just the band.”

The black-and-white, Kodak Tri X Pan photographs Seidemann took of the band rehearsing in the warehouse appear to be from two different days, identifiable because of the change in clothes worn by band members. Joplin’s garb is easiest to describe. In one group of photographs, she’s wearing a T-shirt with the JOB cigarette-papers woman on it. This was probably not a random choice on her part—the image had been popularized by artists Alton Kelley and Stanley Mouse on a poster for a Big Brother show dated October, 7, 1966, at the Avalon Ballroom.

The rest of Joplin’s attire—pin-striped jeans tied at the waist by a braided belt, a pair of kitten-heeled sandals beneath her feet—is defiantly casual, which is surprising since these photographs were definitely taken after Big Brother’s triumphant performances at the Monterey Pop Festival in June of 1967, which means Joplin was on her way to being a full-fledged rock star, and all the wretched excess that implies.

How do we know? Well, in one sequence of photographs, in which Joplin is practicing the maracas with Getz and Andrew, there’s a poster tacked to a wooden post advertising shows by Steve Miller and Little Richard at the Straight Theater on Haight Street. Those shows took place in mid-September of 1967: Since it’s unlikely this poster was produced more than a week or so before those performances, that pegs these rehearsal photos of the band to September of 1967, or later.

It’s not clear if the second set of rehearsal photographs were shot before or after the other group, but the Steve Miller poster is not on the post. That fact doesn’t prove this rehearsal occurred earlier than the other, but it at least suggests that it might have been the case. At any rate, Joplin is a bit more glam for this rehearsal, arriving in sunglasses and a dark overcoat covering a short skirt and matching top, although with the same braided belt around her waist and sandals on her feet. Perhaps Joplin had dressed up a bit in preparation for Monterey Pop, or maybe she was seeing what it would be like to move around in this outfit ahead of several shows scheduled later in the year at the Whisky-A-Go-Go in Los Angeles? Speculate away.

Whatever the timing of Seidemann’s images, by the end of 1967, the band’s exclusive use of the warehouse was coming to an end. “Big Brother only had it for about a year, not much more than that,” Albin says. “After we broke up when Janis left in 1968, Dave and I kept the place. We tried to rehearse there in ’69 when we were looking for other musicians to join the band since both Sam and James had left. James had moved out to the desert, and Sam was touring with Janis. In fact, the warehouse was used to develop Janis’s new band, the Kozmic Blues Band. It was used by several different groups.”

Joplin’s last show with the band was on December 1 at the Avalon Ballroom, where she had made her Big Brother debut; less than two years later, she died of a heroin overdose. But Joplin and the band would live on in the photographs Seidemann had taken of them for a publisher called Berkeley Bonaparte. The resulting posters of Seidemann’s friends sold briskly at head shops around the United States. At the time, they helped define the look expected of would-be hippies heading to San Francisco to participate in the Summer of Love.

“The poster of James projected a persona of the spiritual Indian, with the feathers in his hair and all that,” Getz says. “It played to the image of what Big Brother and the Holding Company was as a band. And the picture of Janis, of course, became like an icon for her—from the look on her face to the beads and the cape, the accouterments of the style she was projecting. Bob captured that.”

For his poster, titled “Mutant,” Getz stood silhouetted in a crooked doorway. For that shot, Getz says, “we went out to the Lawrence Lab in Livermore. Somehow Bob knew about that room with that strange door opening.” On the other side of the doorway was a collage created by Seidemann of a burning Buddhist monk, an exploding hydrogen bomb, and Albert Einstein’s eye, references, no doubt, to a few of the more serious issues on people’s minds during the late 1960s.

For young people looking for images to decorate their walls, Seidemann’s posters were the epitome of cool. “He was Indian Jim, the guitar player for Big Brother, she was the hippie pinup girl,” Albin says of the posters of Gurley and Joplin. “It was all good publicity.”

The rehearsal space at the warehouse, in contrast, was a sanctuary from the hippie hype and marketing machinery that, ironically, was using Seidemann’s posters to lure tens of thousands of kids to San Francisco for the Summer of Love. It was a place where four musicians and a singer could spend a few hours going to work as Big Brother and the Holding Company when no one was watching.

In Living With the Myth of Janis Joplin, Seidemann describes Big Brother as “an organic, natural phenomenon, which grew like a plant from the soil. Janis Joplin became their flower.” In this light, the warehouse on Golden Gate and Van Ness was their garden.

(All images by Bob Seidemann except as noted.)

Read more of Ben’s work on Collectors’ Weekly. Also on Collectors Weekly: Hippie Daredevils, Psychedelic Rock Posters, and When Pianos Fell From the Sky.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.