British painters William Nicholson (1872-1949) and his brother-in-law James Pryde (1866-1941) saw the rising popularity of poster advertising and went for it. In Paris, Toulouse-Lautrec’s posters for the Moulin Rouge were ripped from Montmartre’s street hoardings and stuck up in people’s homes. You could have art in advertising.

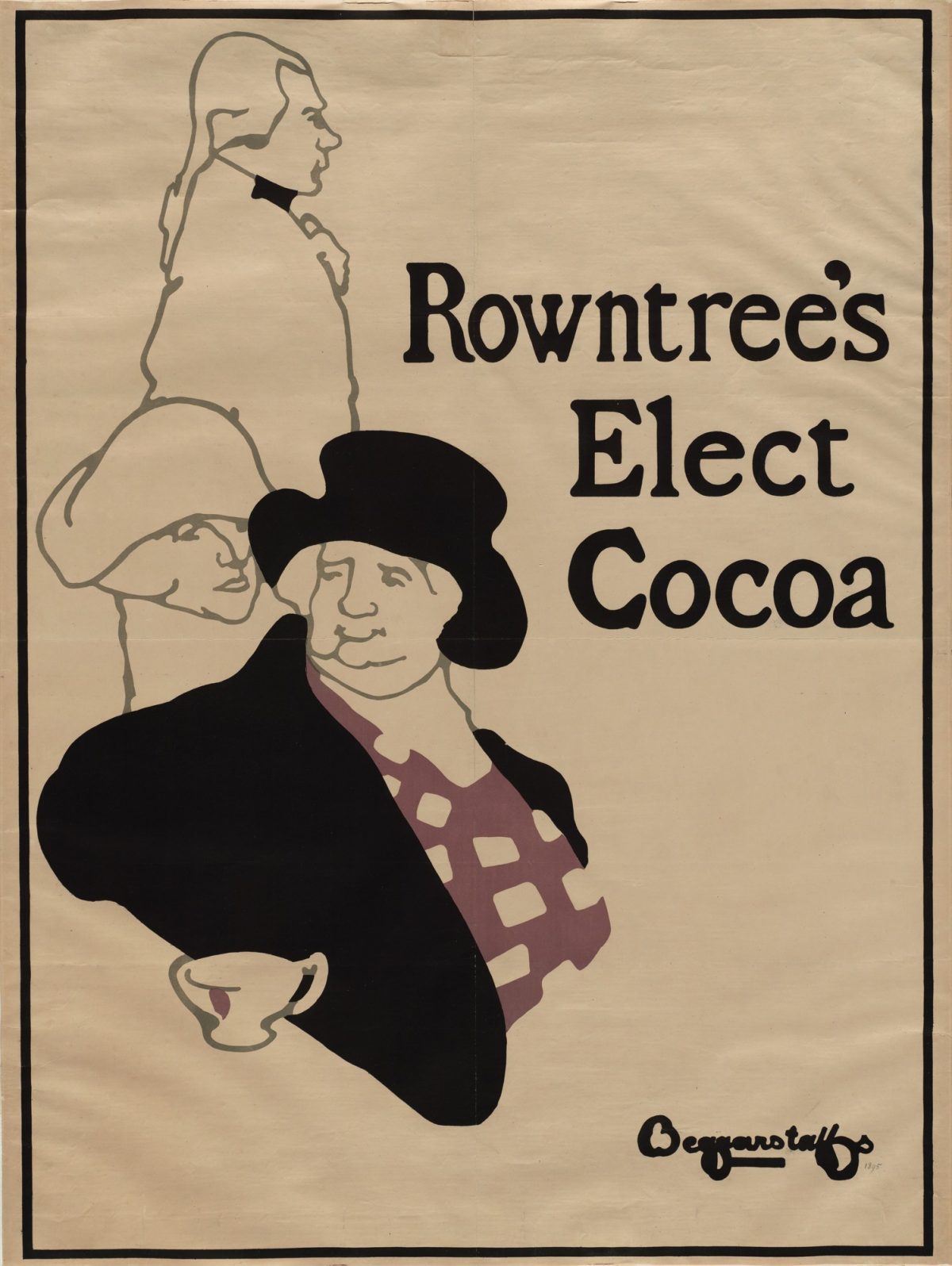

Nicholson and Pryde called their collaboration in poster design ‘Beggarstaffs’ and ‘J. & W. Beggarstaff’ – becoming occasionally known as ‘The Brothers Beggarstaff’, although it was not a name they themselves used.

When a reporter from The Idler asked the artists how they came to choose the soubriquet ‘Beggarstaff’, Nicholson explained: “Pryde and I came across it one day in an old stable, on a sack of fodder. It is a good, hearty, old English name, and it appealed to us; so we adopted it immediately.”

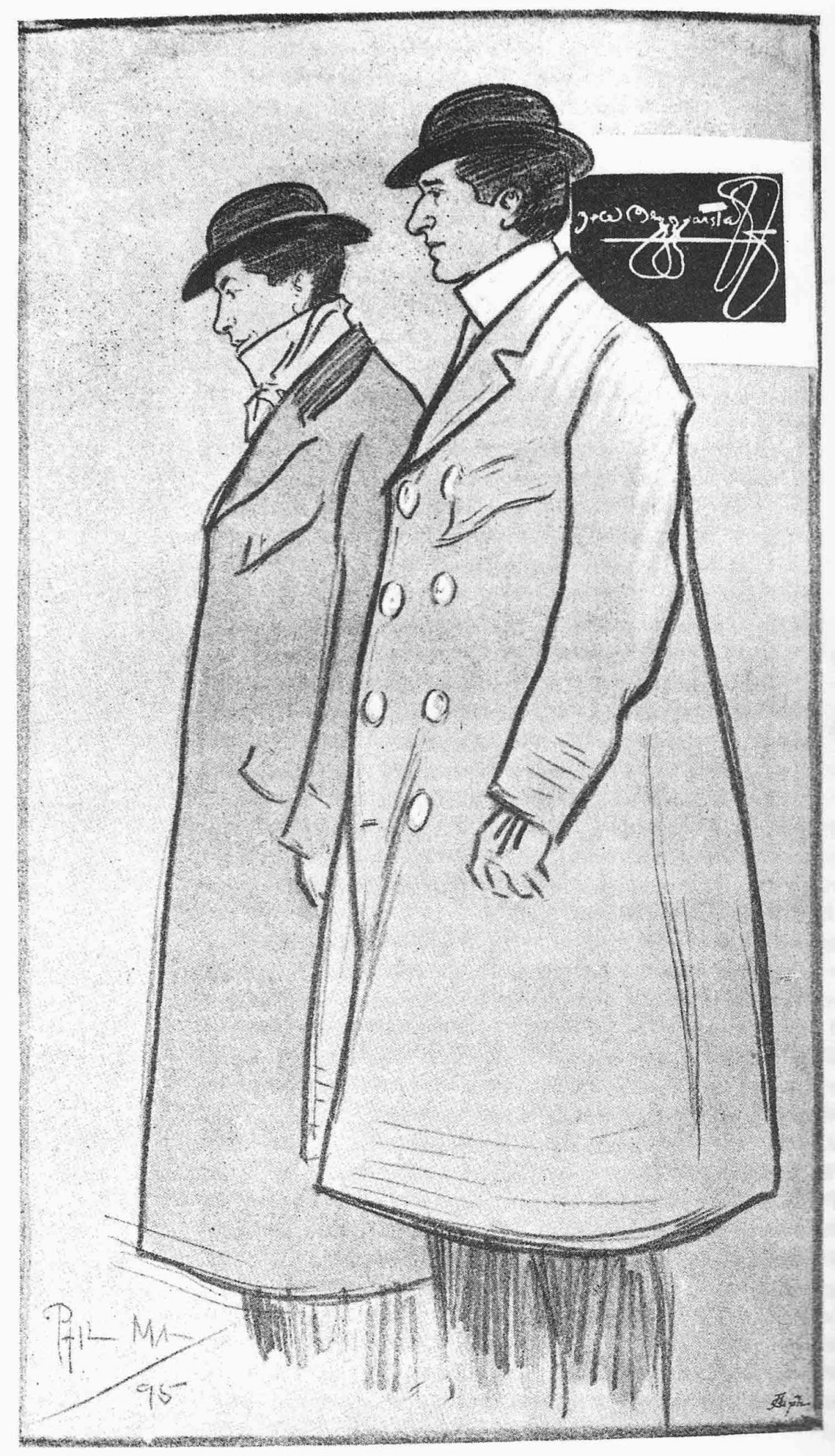

The Beggarstaffs, drawing of William Nicholson (left) and James Pryde by Phil May (1864–1903), first published in The Studio, September 1895 – by Phil May

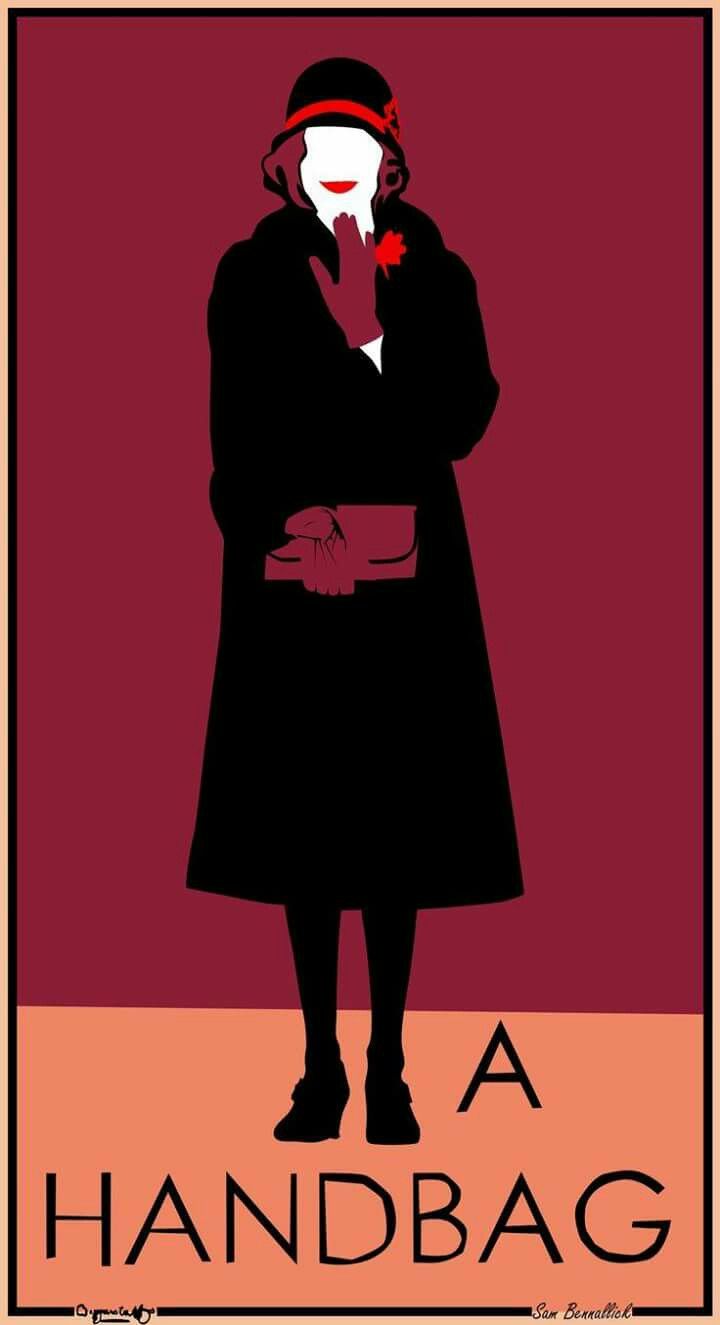

Their innovative print-making process involved collaging cut-paper shapes or stencilling flat colour onto huge sheets of ordinary brown wrapping paper. “Their striking simplicity, relying on outline and silhouette to suggest forms, demonstrated the young artists’ idea that a poster must be effective, even when merely glimpsed from a moving horse-bus,” says Cambridge University’s Fitzwilliam Museum, which staged the first large exhibition of their work.

“The graphics of J & W Beggarstaff were pared down to only essential lines and monotones: they were all about the omission of extraneous detail,” writes Michael Prodger, “three dimensionality and decorous colour and composition. In its simplicity and clarity their work anticipated the modernist aesthetic by a decade.”

Their first commission was from a friend, the actor Edward Gordon Craig. In the summer of 1894 Craig was preparing to go on tour with the Shakespearean Company of W.S. Hardy, for whom he was to play Hamlet. He asked Pryde and Nicholson to design and produce a poster to publicise the production.

As Colin Campbell writes in The Beggarstaff Posters: The Work of James Pryde and William Nicholson. London: Barrie & Jenkins (1990), the initial design was made partly by collage, the hair and clothing of Craig as Hamlet cut from plain black paper; the life-sized figure in the printed version used to publicise the play was stencilled on brown wrapping-paper by Nicholson, with some details added by hand. It was reproduced in four publications: the Magazine of Art, La Plume, Pictorial Posters (all 1895) and The Poster (1899).

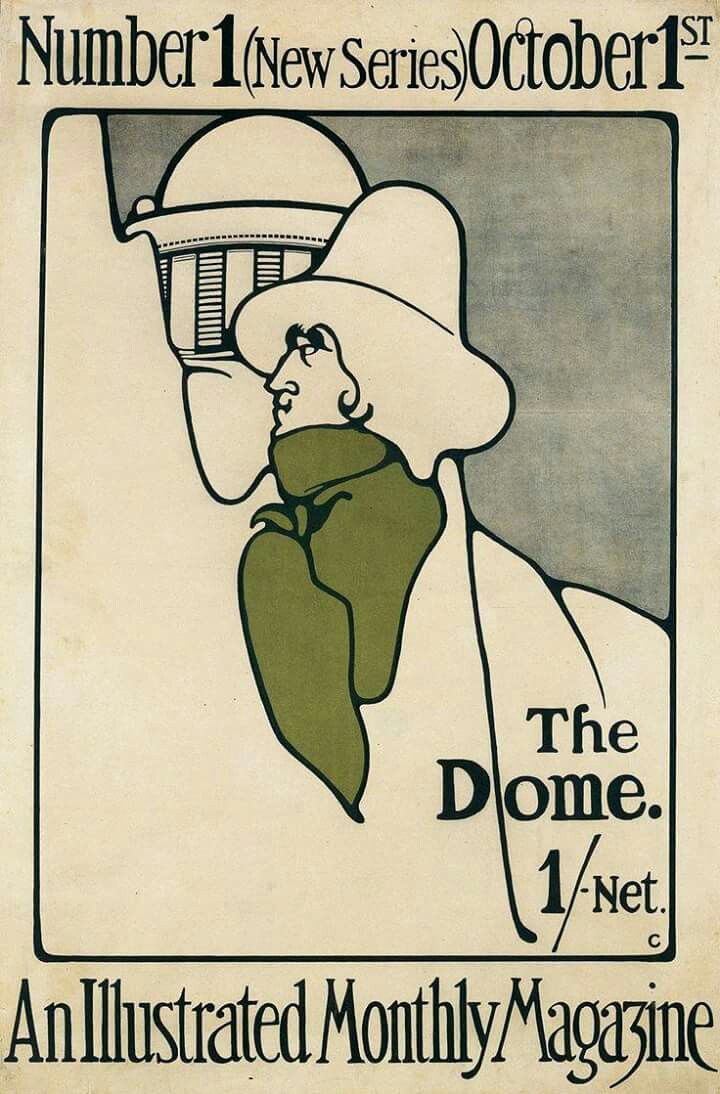

James Pryde – cover for The Poster, February 1899

As Anne Garvey adds, Beggarstaffs’ daring posters were well reviewed:

Cinderella [lead image] was a poster for a Christmas show [on London’s Drury Lane]… The original giant poster unfurled before a deeply unimpressed theatre manager about to turn it down when an influential critic strolled in and began to compliment him on his wonderful taste. The Brothers Beggarstaff was in business.

But their posters were to prove too avant-garde for the advertisers of their day. The business died. Pryde and Nicholson resumed their individual careers as painters.

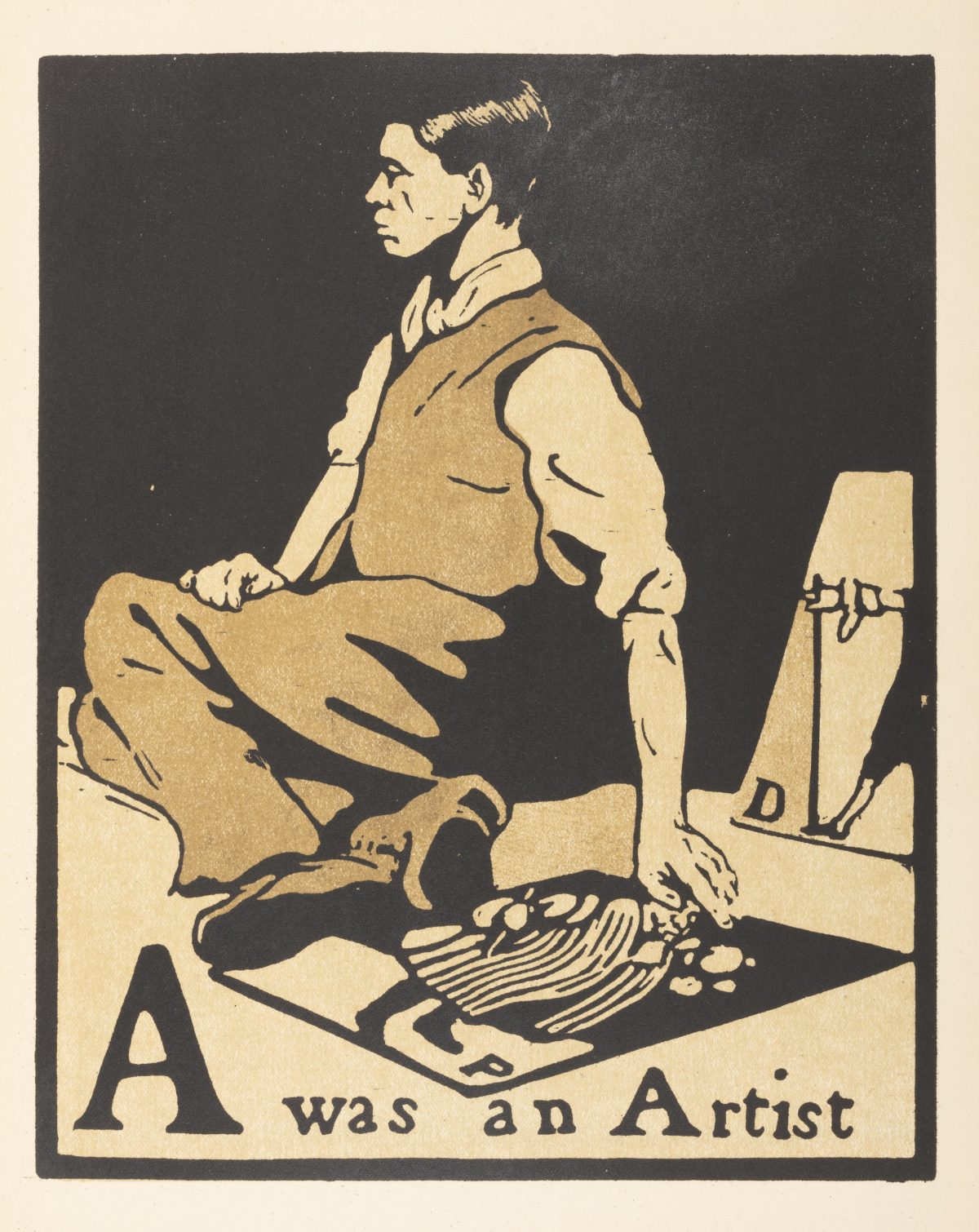

Nicholson took up wood engraving, working with publishers William Heinemann, for which he illustrated the books An Alphabet, An Almanac of Sports and London Types.

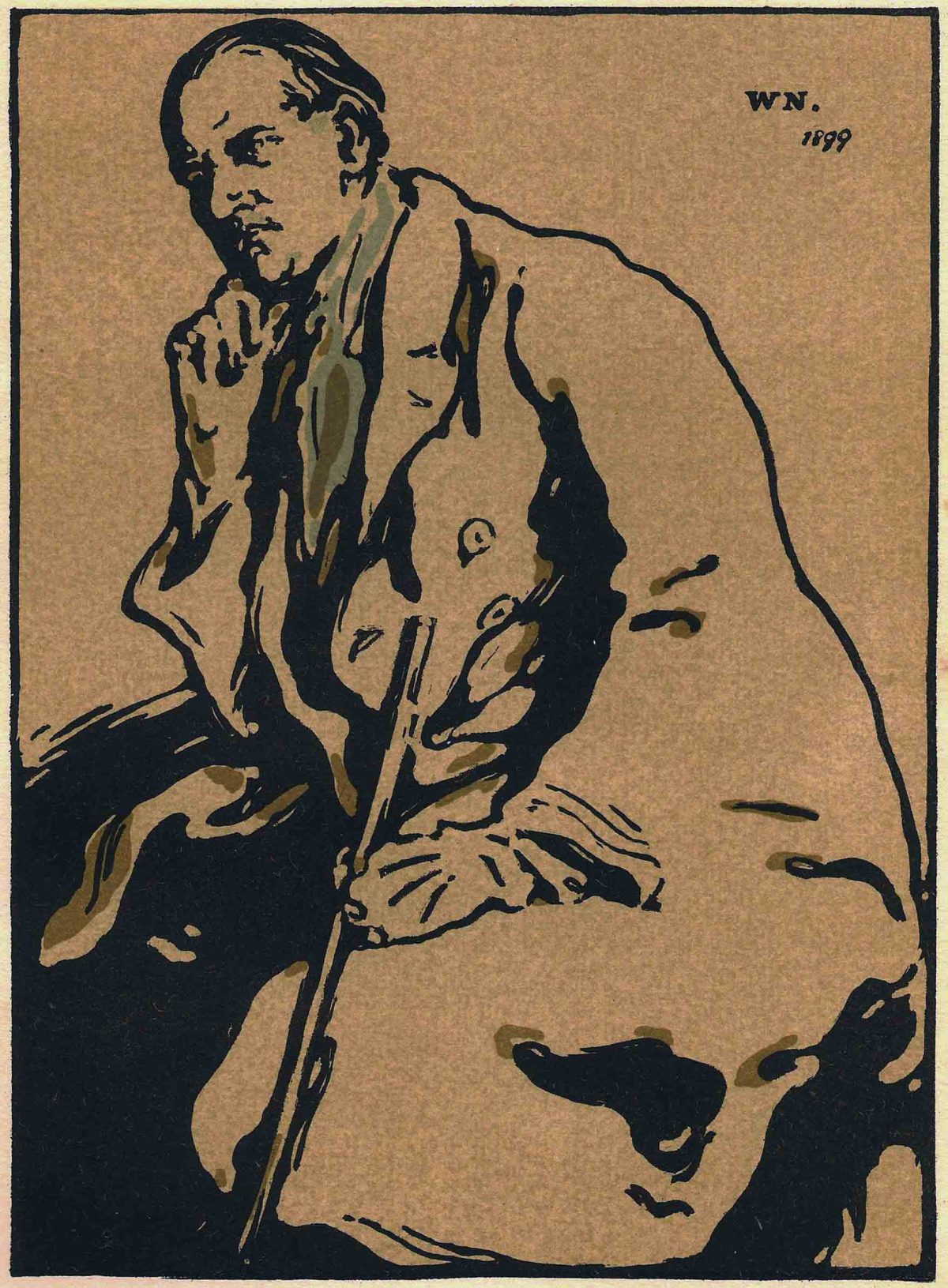

Portrait of James Pryde by William Nicholson, woodcut, 1899; published in The Studio, July 1901

Canadian Headquarters Staff, 1918 – Canadian War Museum, Beaverbrook Collection of War Art

Nicholson was a star. “Some art-lovers will already think they know a bit about one half of the Beggarstaffs – Sir William Nicholson – as painter of gleaming silver and lushly, luxurious roses, who became a pillar of the artistic establishment, sought out as a portraitist, awarded a knighthood, and quite as grand as he appears in the Fitz’s portrait of him by Augustus John,” says Luke Syson, Director of the Fitzwilliam Museum.

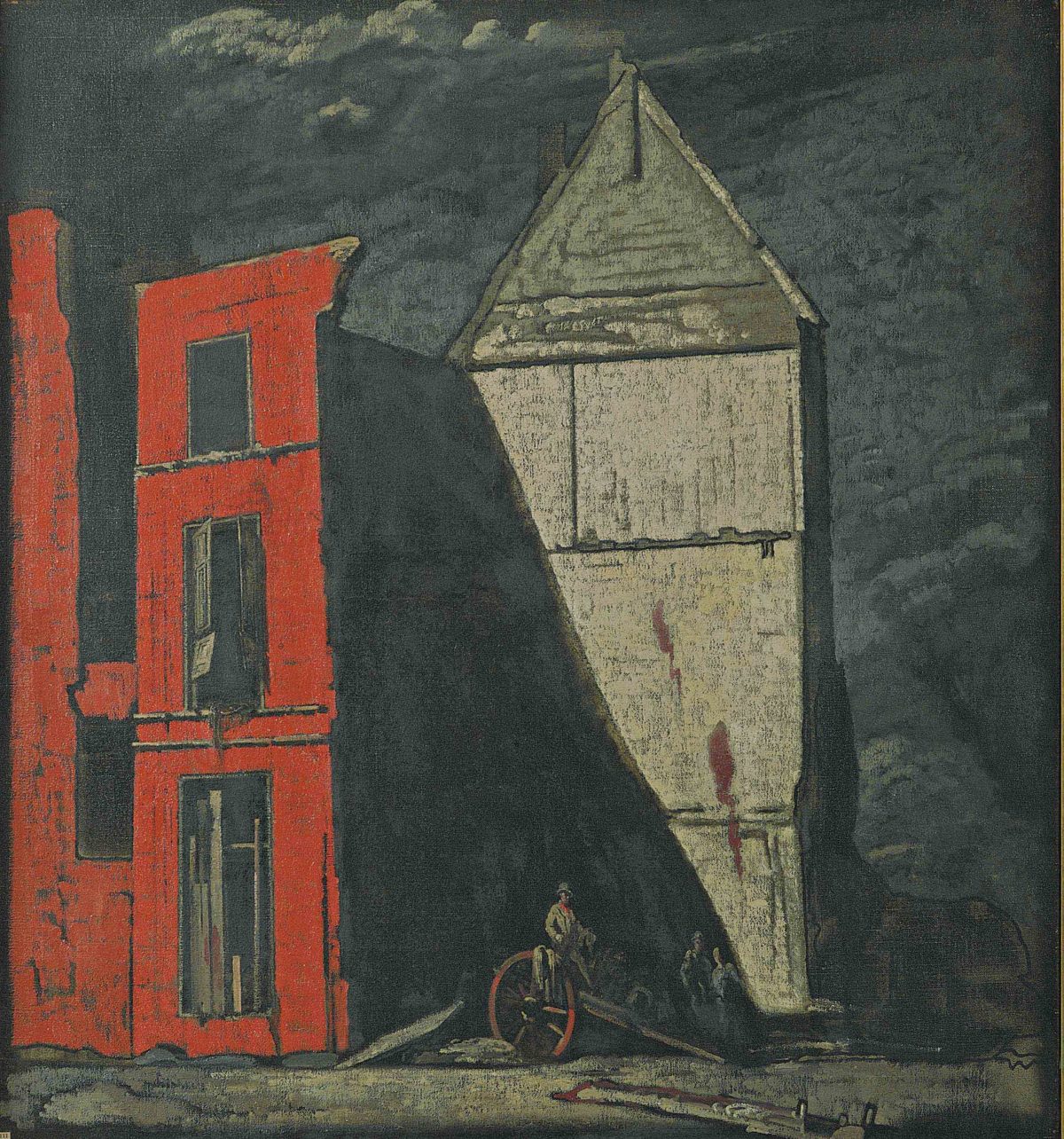

The Red Ruin. Oil on canvas, 154.4 x 141 cm – James Pryde (1866–1941)

Pryde, on the other hand, like the 17th-century creators of architectural fantasy landscapes, worked essentially from the imagination, inventing dark ‘sinister corners’ and ‘death beds’ that appear as stage-sets conjured from childhood memories of Edinburgh’s Old Town and Mary Queen of Scot’s bedchamber at Holyrood Palace. Pryde’s productivity would never equal Nicholson’s and gradually he stopped painting altogether as his life became more chaotic.

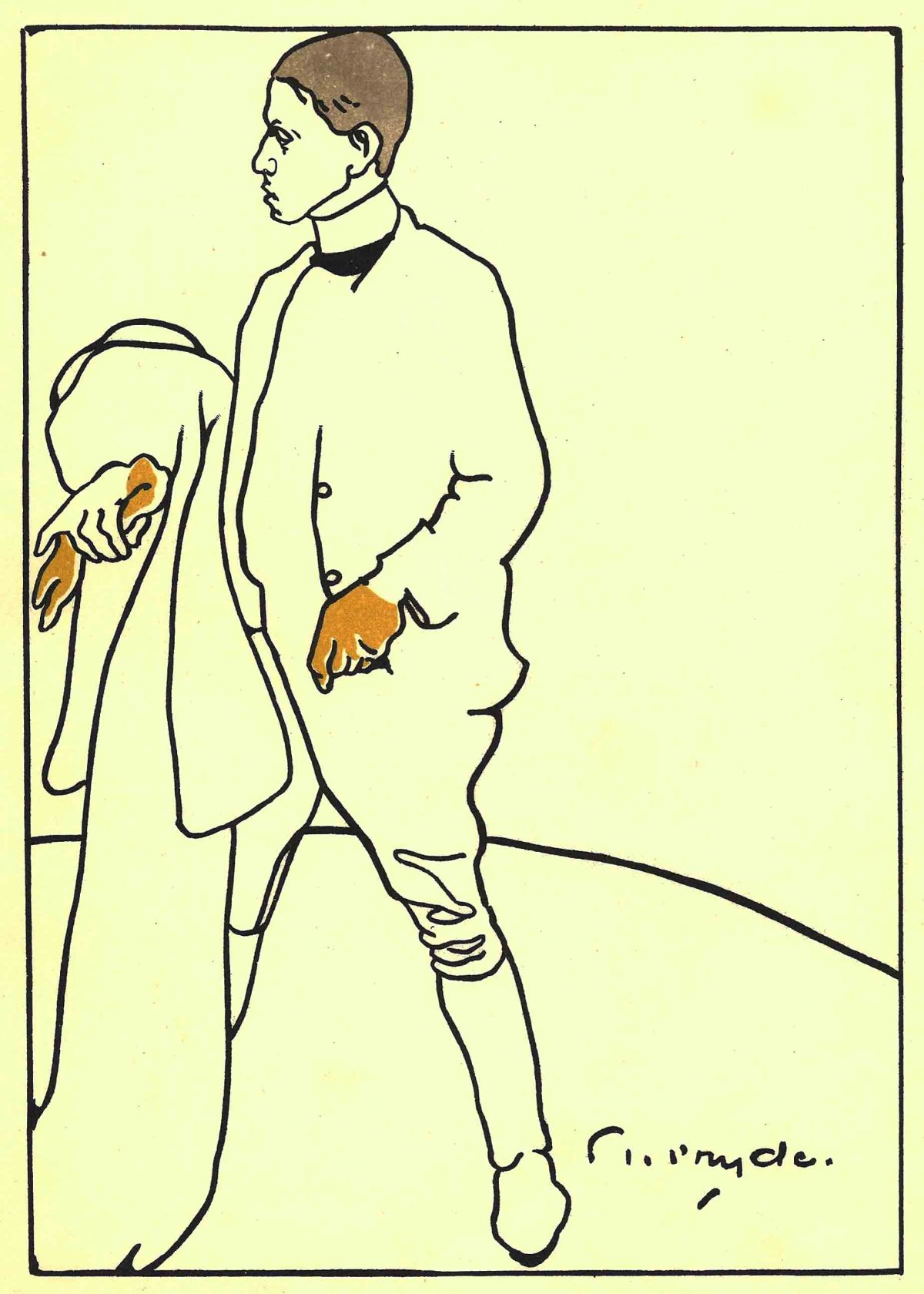

Portrait Study of W.P. Nicholson, lithograph portrait of William Nicholson by James Pryde, published in The Studio, December 1897

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.