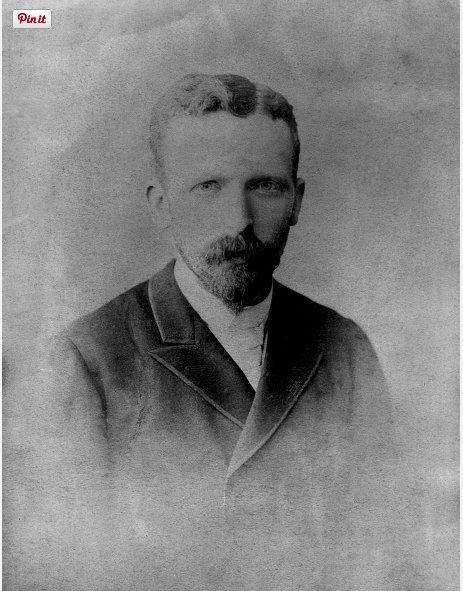

Is that Vincent Van Gogh in this 1887 melainotype? Is he with Paul Gauguin and Emile Bernard, as some believe?

Picture expert Serge Plantureux recalls his feelings when two men brought him the picture. He tells L’Oeil de la Photographie:

The photograph they had brought to show me was small, dark, and rather difficult to see. Six characters were around a table. The light was pale, perhaps it was a winter afternoon.

They told me, still hesitant, that they thought they recognized the people in it, artists in whom they had long been interested. They were collectors and liked the painters of the late 19th century, in particular the neo-impressionists. They also said it was possible that one of the figures around the table was someone whose true face had never been seen.

Is it Van Gogh?

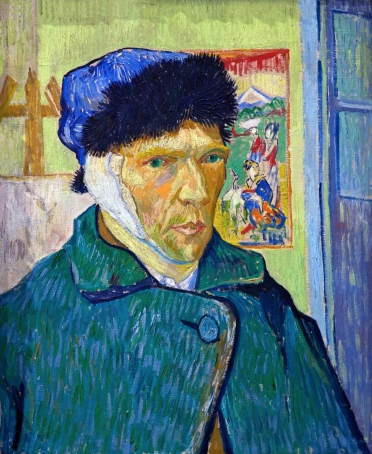

Another expert, this time from the Van Gogh museum in Amsterdam, says it can’t be the Van Gogh “because it simply does not look like him”, and, in any case, the artist hated to be photographed.

Did Van Gogh fail to see the power of the photograph; or did he realise its immense, lazy, insecure power to control and own the subject?

Susan Sontag noted in 1977:

Photographs are perhaps the most mysterious of all the objects that make up, and thicken, the environment we recognize as modern. Photographs really are experience captured, and the camera is the ideal arm of consciousness in its acquisitive mood.

To photograph is to appropriate the thing photographed. It means putting oneself into a certain relation to the world that feels like knowledge — and, therefore, like power… Photographic images… now provide most of the knowledge people have about the look of the past and the reach of the present. What is written about a person or an event is frankly an interpretation, as are handmade visual statements, like paintings and drawings. Photographed images do not seem to be statements about the world so much as pieces of it, miniatures of reality that anyone can make or acquire…

Photographs, which cannot themselves explain anything, are inexhaustible invitations to deduction, speculation, and fantasy.

Photography implies that we know about the world if we accept it as the camera records it. But this is the opposite of understanding, which starts from not accepting the world as it looks. All possibility of understanding is rooted in the ability to say no. Strictly speaking, one never understands anything from a photograph.

Van Gogh preferred to present himself though his art, writing in his letters to his brother Theo:

“Everyone who works with love and with intelligence finds in the very sincerity of his love for nature and art a kind of armor against the opinions of other people…

“What am I in the eyes of most people? A good-for-nothing, an eccentric and disagreeable man, somebody who has no position in society and never will have. Very well, even if that were true, I should want to show by my work what there is in the heart of such an eccentric man, of such a nobody.”

To Van Gogh, art was the authentic expression of self:

“Do you know that it is very, very necessary for honest people to remain in art? Hardly anyone knows that the secret of beautiful work lies to a great extent in truth and sincere sentiment.”

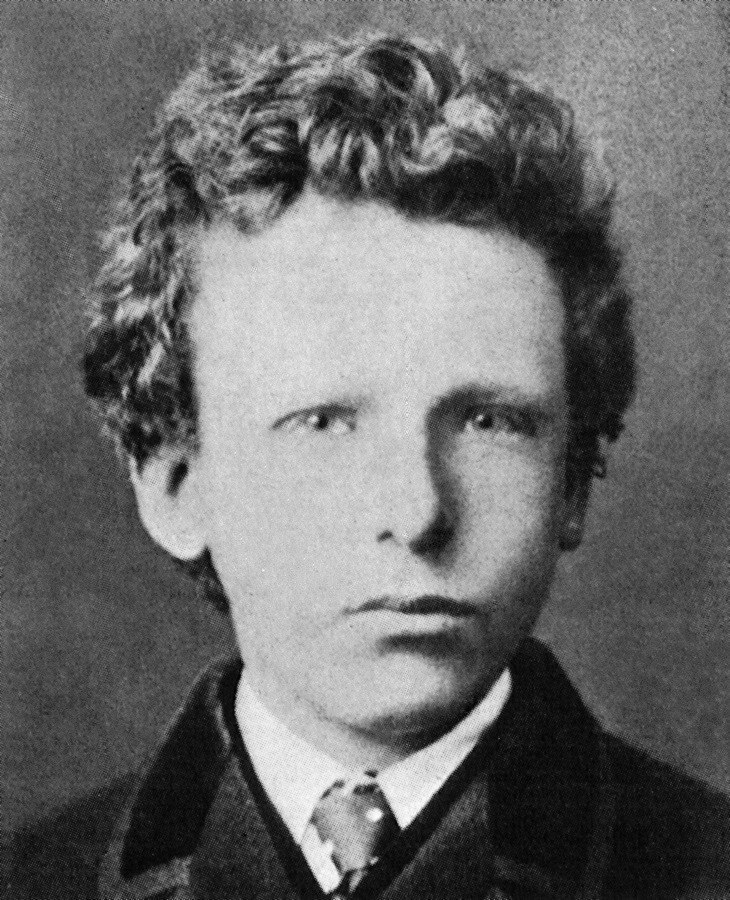

cent c. 1873 aged 19. This photograph was taken at the time when he was working at the branch of Goupil & Cie’s gallery in The Hague.

“What is drawing? How does one get there? It’s working one’s way through an invisible iron wall that seems to stand between what one feels and what one can do. How can one get through that wall? — since hammering on it doesn’t help at all. In my view, one must undermine the wall and grind through it slowly and patiently. And behold, how can one remain dedicated to such a task without allowing oneself to be lured from it or distracted, unless one reflects and organizes one’s life according to principles? And it’s the same with other things as it is with artistic matters. And the great isn’t something accidental; it must be willed. Whether originally deeds lead to principles in a person or principles lead to deeds is something that seems to me as unanswerable and as little worth answering as the question of which came first, the chicken or the egg.

“But I believe it’s a positive thing and of great importance that one should try to develop one’s powers of thought and will.”

Spotters: PetaPixel, Hyperallergic

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.