In 1991, the ongoing scandal of cigarette advertising in the U.S. reached an ugly climax, after decades of deception, when the American Medical Association revealed findings that young children more easily recognized Camel mascot Joe Camel than characters like Barbie or Mickey Mouse. The revelation ended the Joe Camel campaign. It also marked the beginning of bans and heavy restrictions on tobacco advertising in countries around the world in response to calls from medical associations like the AMA, World Health Organization, and the Royal College of Physicians.

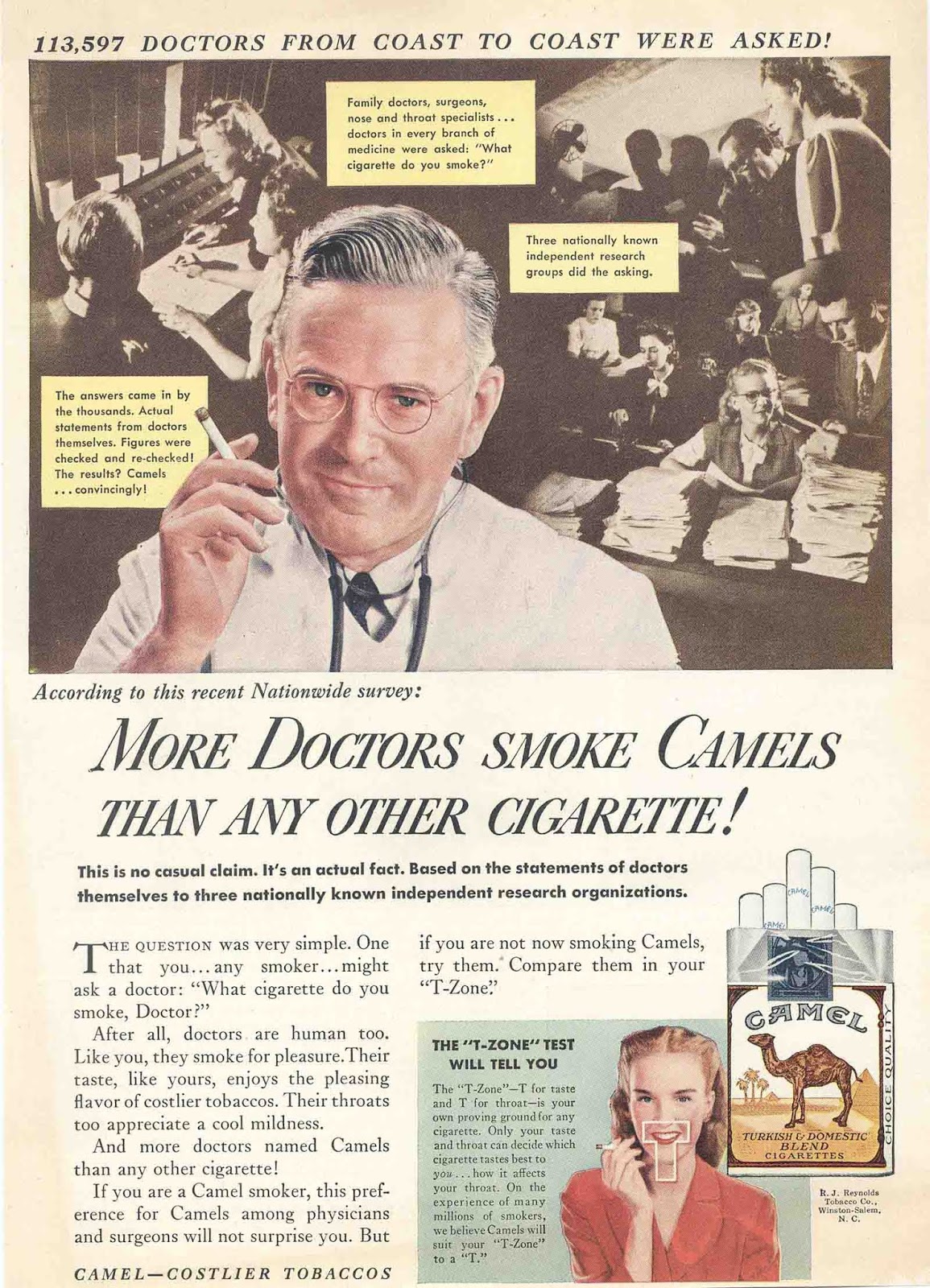

But there was a time when doctors actively promoted cigarettes—or at least appeared to—in dozens of ads with supposedly authoritative testimonials from physicians. One of the most successful of these campaigns came from Camel, whose parent company RJ Reynolds launched the ad above in 1946 touting a nationwide survey showing that “More Doctors Smoke Camels Than Any Other Cigarette!” The ad declared its research methods sound: “Three nationally known independent research groups did the asking,” it claimed. And it introduced nonsensical but technical-sounding terms like the “’T-Zone Test” to appear more rigorously scientific.

In actual fact, write medical researchers Martha Gardner and Allan Brandt, “this “independent” surveying was conducted by RJ Reynolds’s advertising agency, the William Esty Company, whose employees questioned physicians about their smoking habits at medical conferences and in their offices. It appears that most doctors were surveyed about their cigarette brand of choice just after being provided complimentary cartons of Camels” The campaign proved so popular that the “more doctors” slogan “would be the mainstay of [Camel] advertising for the next 6 years,” including ads clearly meant to appeal to parents and young kids.

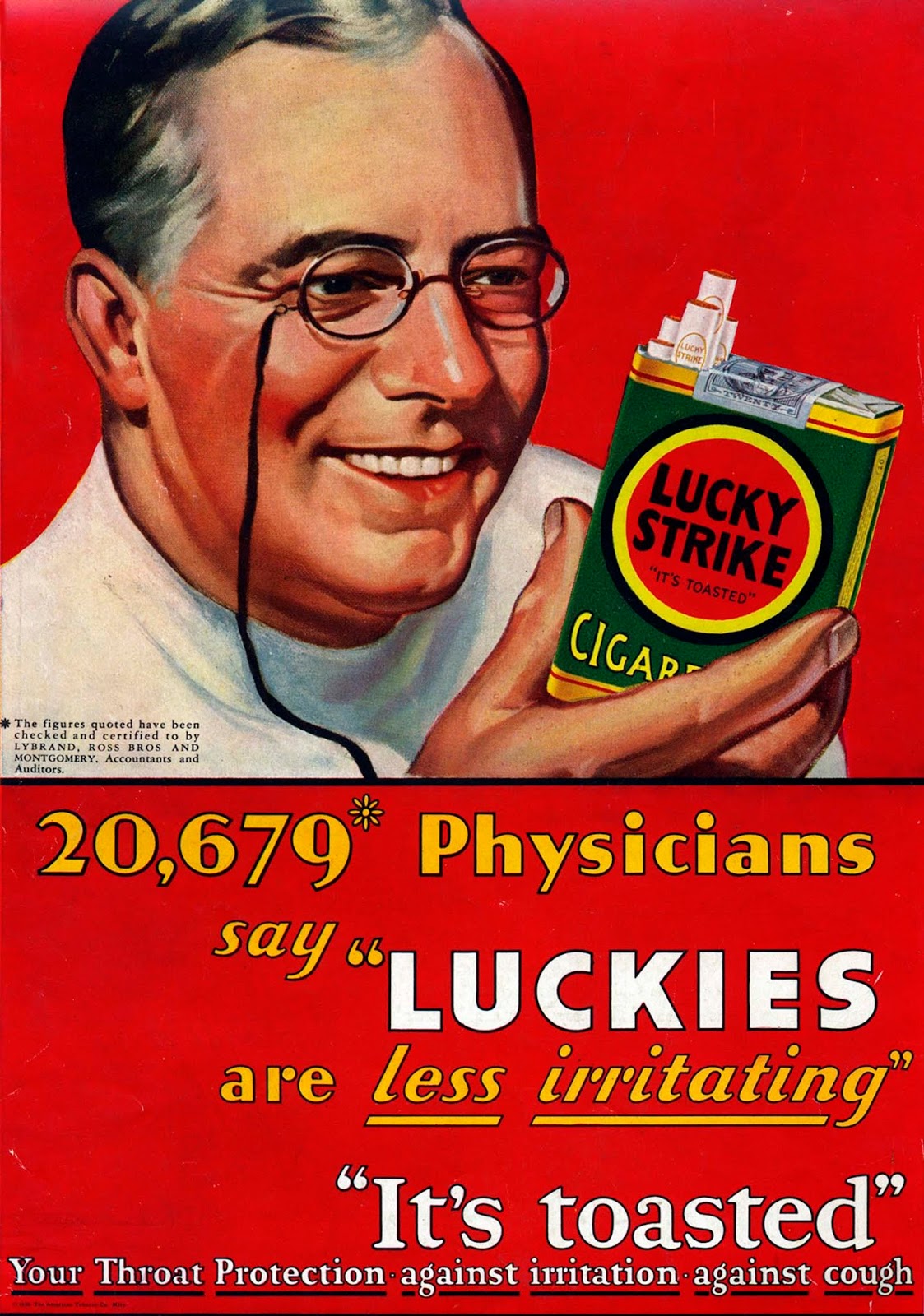

The Camel campaign was hardly the first, nor the last, to prominently feature doctors endorsing tobacco use. Tobacco had been promoted as a cure-all by “druggists” since the late 19th century. In 1927, the American Tobacco Company began a campaign for Lucky Strike “by claiming that 11,105 physicians endorsed Luckies as ‘less irritating to sensitive or tender throats than any other cigarettes.” (This number almost doubled in later ads to “20,679 Physicians.”) Doubtless, similar methods were used to collect the “data.” Doctors did not sit idly by and allow their profession to be commandeered by big tobacco.

Alan Blum, MD, editor of the New York State Journal of Medicine, documents the reaction from the publication at the time, whose lawyer Lloyd Paul Stryker issued a statement denouncing the ads. When “non-therapeutic agents such as cigarettes are advertised as having the recommendation of the medical profession, the public is thereby led to believe that some real scientific inquiry has been instituted, and that the endorsement is the result of painstaking and accurate inquiry as to the merits of the product.” Later tobacco company pronouncements notwithstanding, no such painstaking inquiry had ever shown cigarette smoking to be healthy—on the contrary, as the public would slowly learn over time.

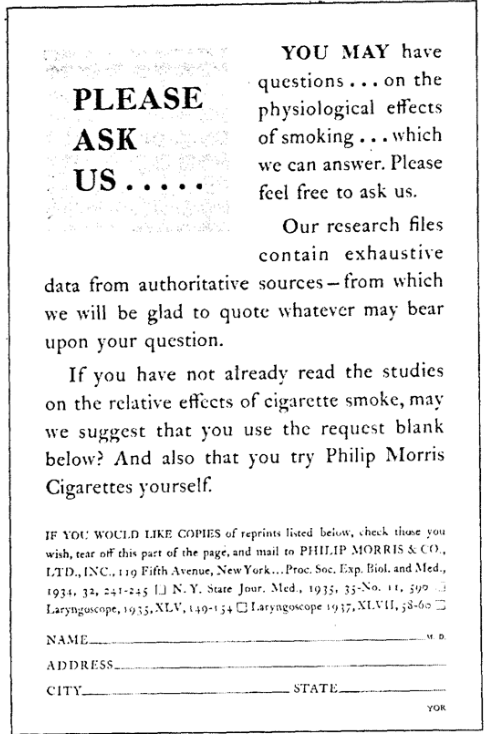

Nonetheless, the Journal began accepting cigarette ads in its own pages in 1933 and would run more than 600 pages of such ads from the six major tobacco companies over the next 20 years. The only advertisement from Lucky Strike touted “a quarter century of research related to a light smoke.” Readers could write Philip Morris to receive their own copy of a “a graph purportedly illustrating the ratio of total volatile acids to total volatile bases,” writes Blum, a supposedly “objective technique for the measurement of irritation.” These claims were consistent with the tenor of the so-called scientific research presented by cigarette makers.

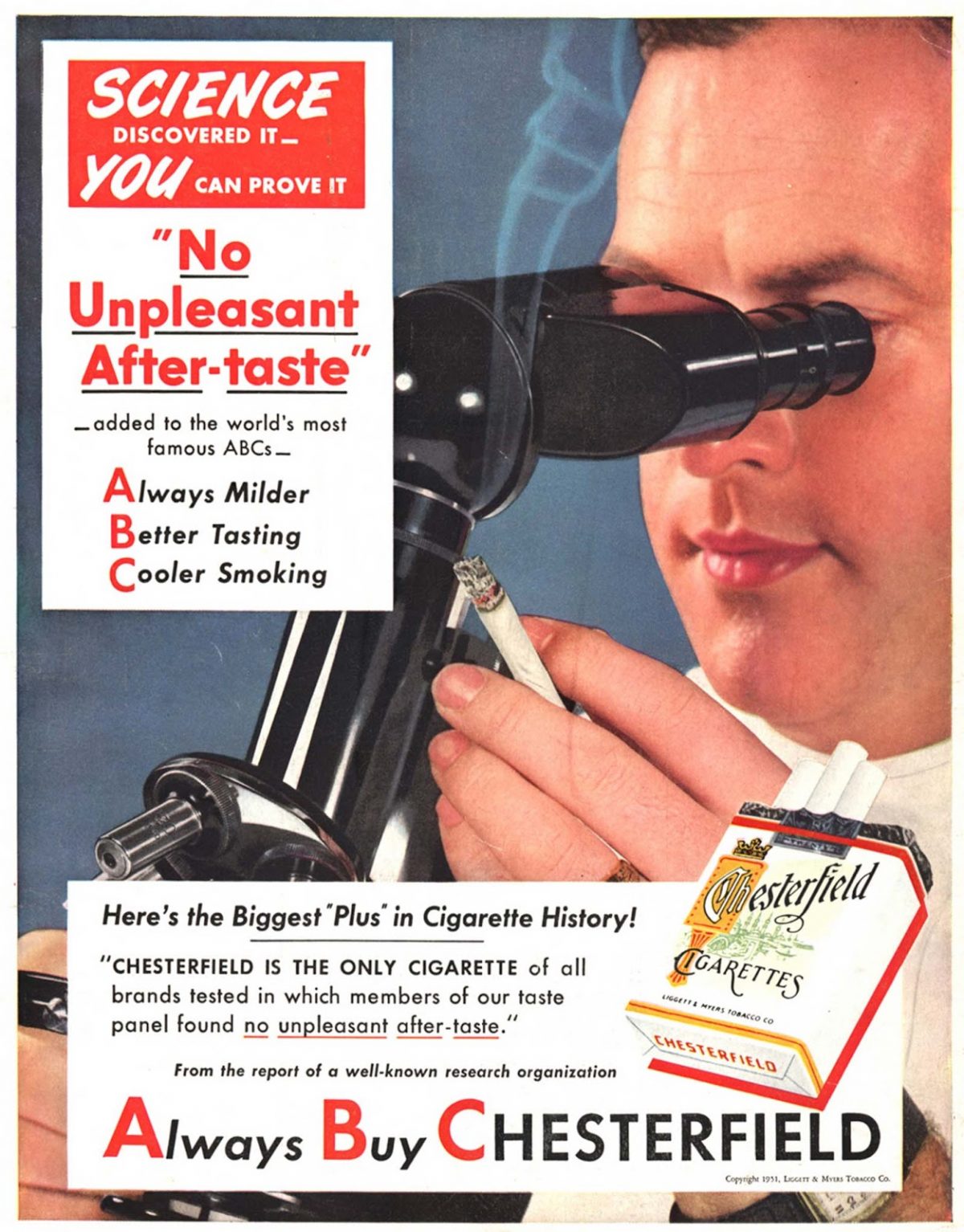

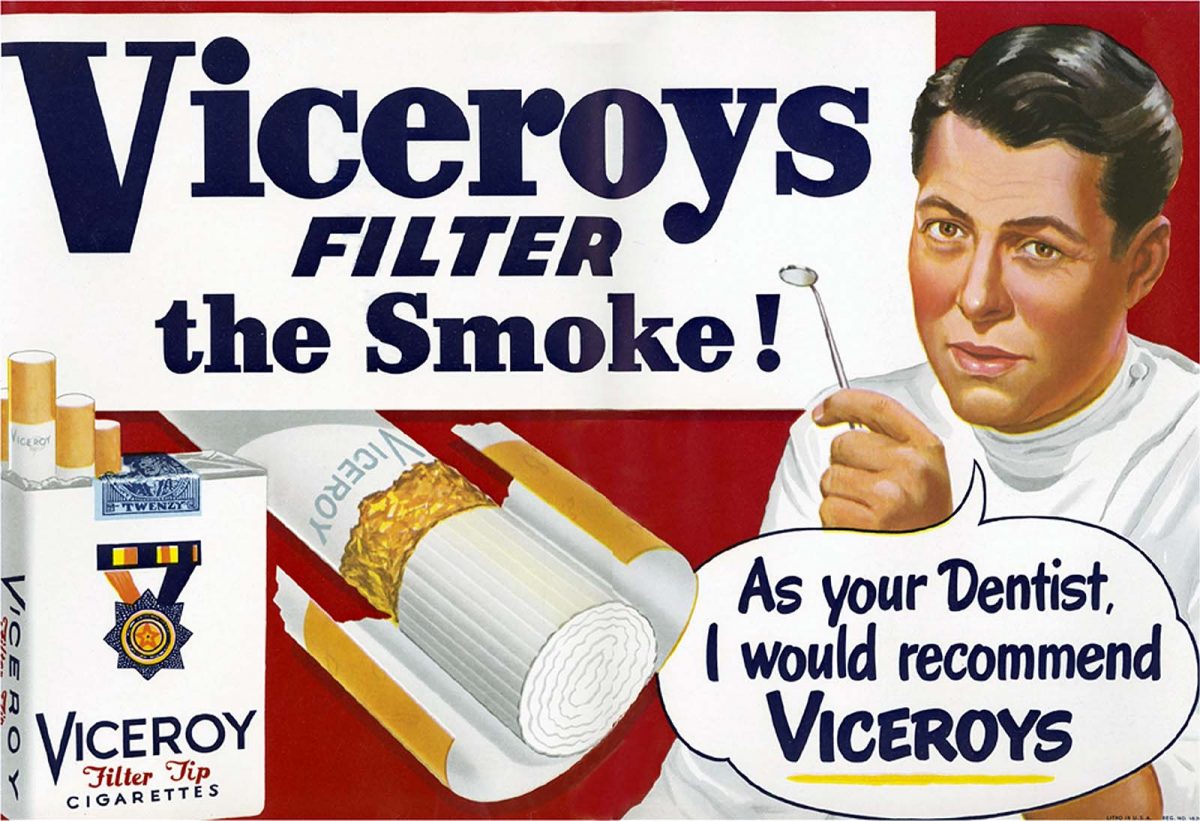

No company would go as far as claiming that their competitors’ products harmed consumers – thereby casting doubt on tobacco use generally. Instead, they promised their products were scientifically verified to taste better and be “less irritating,” an admission that cigarette smoke was always “irritating” in some degree. Even dentists were shown promoting certain brands over others. As television took primacy over print, tobacco companies took to running with actors playing doctors on TV. When the links between cigarette smoking and lung cancer became impossible for tobacco companies to ignore in the mid-fifties, with findings appearing in popular magazines like Time and Reader’s Digest, even these tempered “medical” assertions had to be put aside for other kinds of appeals with which we’re well familiar.

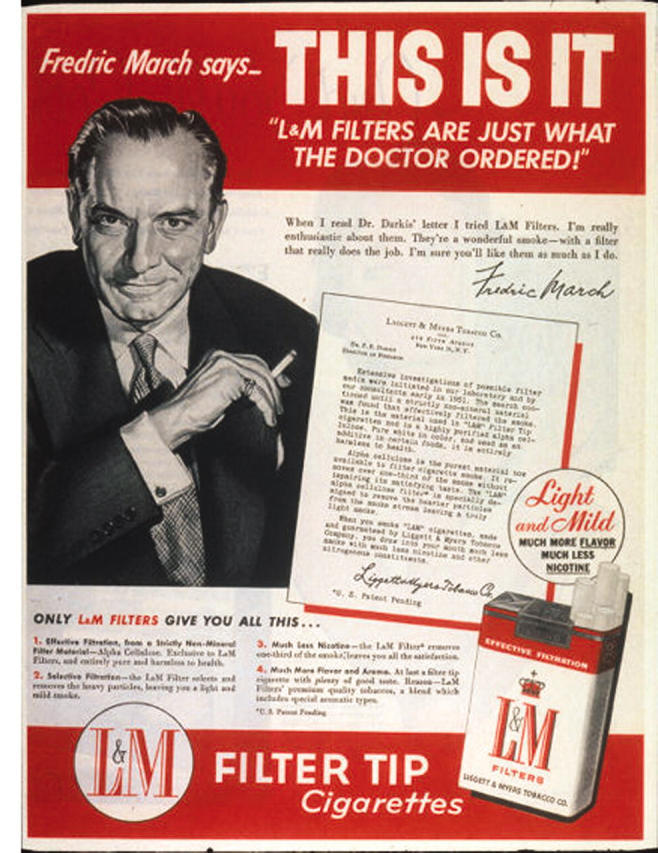

“Company executives realized that they would have to work together in the face of the scientific evidence,” write Gardner and Brandt. “Although each company still sought an advantage over its competitors, the new health evidence threatened the future of the entire industry.” Prominent public relations firm Hill & Knowlton concluded on behalf of the industry as a whole that “health claims were considered to be no longer viable.” Liggett & Meyers, the only company to decline participation in this joint industry program, ran the last ad to feature “notable reference to doctors” in 1954—a slyly oblique celebrity endorsement from Hollywood star Fredric March with the tagline, “L&M Filters Are Just What the Doctor Ordered.”

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.