If English essayist Walter Pater (4 August 1839 – 30 July 1894) was right in his belief that “all art constantly aspires to the condition of music”, we should cock and ear to what Elliott Schwartz (January 19, 1936–December 7, 2016) had to say about listening. In his Music: Ways of Listening (1982), the American composer and music teacher lists the seven essential skills for listening to music.

As the book’s preface says, Music: Ways of Listening “is intended for use in introductory college courses for students with little or no prior background in music, and is focused upon the development of perceptive listening skills and a broad survey of the Western concert literature…

“There is no attempt made to teach students the written ‘language’ of Western music, but, rather, an introduction to the “linguistics” of written symbols in all musical cultures.”

The 7-Point Guide To Music Appreciation:

Develop your sensitivity to music. Try to respond esthetically to all sounds, from the hum of the refrigerator motor or the paddling of oars on a lake, to the tones of a cello or muted trumpet. When we really hear sounds, we may find them all quite expressive, magical and even ‘beautiful.’ On a more complex level, try to relate sounds to each other in patterns: the successive notes in a melody, or the interrelationships between an ice cream truck jingle and nearby children’s games.

Time is a crucial component of the musical experience. Develop a sense of time as it passes: duration, motion, and the placement of events within a time frame. How long is thirty seconds, for example? A given duration of clock-time will feel very different if contexts of activity and motion are changed.

Develop a musical memory. While listening to a piece, try to recall familiar patterns, relating new events to past ones and placing them all within a durational frame. This facility may take a while to grow, but it eventually will. And once you discover that you can use your memory in this way, just as people discover that they really can swim or ski or ride a bicycle, life will never be the same.

If we want to read, write or talk about music, we must acquire a working vocabulary. Music is basically a nonverbal art, and its unique events and effects are often too elusive for everyday words; we need special words to describe them, however inadequately.

Try to develop musical concentration, especially when listening to lengthy pieces. Composers and performers learn how to fill different time-frames in appropriate ways, using certain gestures and patterns for long works and others for brief ones. The listener must also learn to adjust to varying durations. It may be easy to concentrate on a selection lasting a few minutes, but virtually impossible to maintain attention when confronted with a half-hour Beethoven symphony or a three-hour Verdi opera. Composers are well aware of this problem. They provide so many musical landmarks and guidelines during the course of a long piece that, even if listening ‘focus’ wanders, you can tell where you are.

Try to listen objectively and dispassionately. Concentrate upon ‘what’s there,’ and not what you hope or wish would be there. At the early stages of directed listening, when a working vocabulary for music is being introduced, it is important that you respond using that vocabulary as often as possible. In this way you can relate and compare pieces that present different styles, cultures and centuries. Try to focus upon ‘what’s there,’ in an objective sense, and don’t be dismayed if a limited vocabulary restricts your earliest responses.

Bring experience and knowledge to the listening situation. That includes not only your concentration and growing vocabulary, but information about the music itself: its composer, history and social context. Such knowledge makes the experience of listening that much more enjoyable.

There may appear to be a conflict between this suggestion and the previous one, in which listeners were urged to focus just on ‘what’s there.’ Ideally, it would be fascinating to hear a new piece of music with fresh expectations and truly innocent ears, as though we were Martians. But such objectivity doesn’t exist. All listeners approach a new piece with ears that have been ‘trained’ by prejudices, personal experiences and memories. Some of these may get in the way of listening to music. Try to replace these with other items that might help focus upon the work, rather than individual feelings. Of course, the ‘work’ is much more than the sounds heard at any one sitting in a concert hall; it also consists of previous performances, recorded performances, the written notes on manuscript paper, and all the memories, reviews and critiques of these written notes and performances, ad infinitum. In acquiring information about any of these factors, we are simply broadening our total awareness of the work itself.

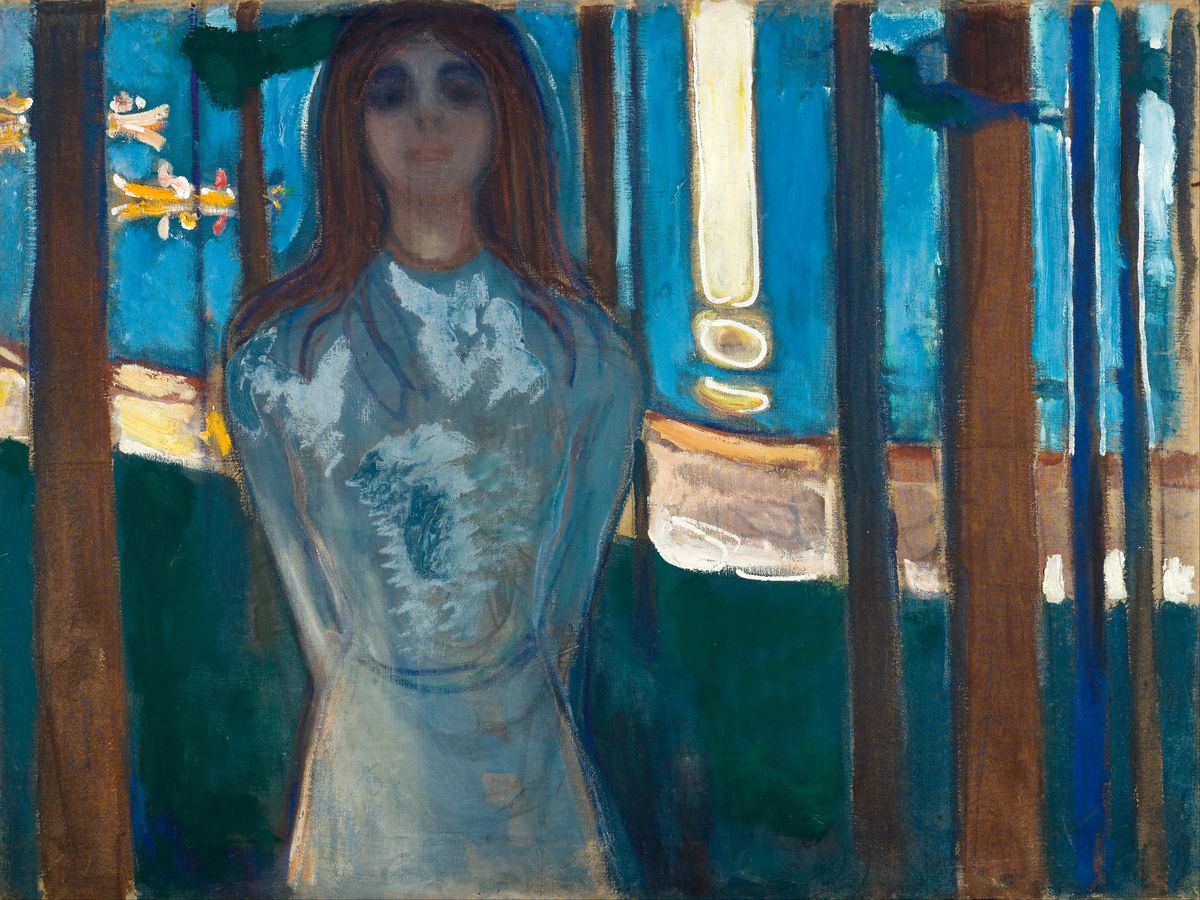

The Queen of the Night, from Mozart’s Magic Flute, (Zauberflöte) – buy prints

The Art of Listening

Schwartz was a man of letters. He was (deep breath) President of the College Music Society, National Chair of the American Society of University Composers (now renamed the Society of Composers), Vice-President of the American Music Center, President of the Maine Composers Forum, and music panelist for the Maine Arts Council. He was also a board member of the American Composers Alliance.

He was Beckwith Professor Emeritus of music at Bowdoin College joining the faculty in 1964. In 2006, the Library of Congress acquired his papers to make them part of their permanent collection.

And he embraced the new, writing Electronic Music: A Listener’s Guide, Music Since 1945, co-authored with Daniel Godfrey. According to the obituary in the Portland Press Herald: “He composed one piece based on actual Facebook posts, which included musicians reading the posts, while another piece featured TVs and radios on stage with the performers. His 1966 piece “Elevator Music” was performed by 12 small groups on various floors of a building, while the audience rode an elevator and heard parts of the piece on each floor.”

In an interview in 1987, Schwartz confronted the assumption that music is something other people do. To him, music was participatory:

It should be, and this ought to be one of the chief aspects of any comprehensive musical education program — a sense of installing in everyone the feeling that what’s most exciting about music is that everybody does it at some level of competency (or incompetency), or just that everybody does it, and everybody can have an enormously arching experience doing it.

Music is Universal

Put aside you prejudices and listen:

“I wish I could tell you where I read it, but there was a marvelous article somewhere that compared the aestheticians view of ‘art as the beautiful’ to the pedestal men used to put women on; you know, the chivalrous attitude of admiring at a distance, which was a way in both cases of never really coming to grips with the objects. They were always dealing with them so respectfully and so worshipfully that you would really rob them of all their humanity and all the interesting aspects about them.

..

“…when you begin thinking of pieces of music as beautiful, you’re not responding to them anymore. It means you’ve attached a label to them and then you file them away in the part of your brain that says ‘beautiful’. I would just assume that they’re living, and they’re vibrant, and they get people angry, and they make people laugh. They stimulate real responses rather than aesthetic ones, which I don’t think are real.”

Lead Image: Metropolitan Opera House, New York – 28 November 1937

Via: The Marginalian, LoC

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.