Interviewer: “Mr Nabokov, would you tell us why it is that you detest Dr. Freud?”

Vladimir Nabokov: “I think he’s crude, I think he’s medieval, and I don’t want an elderly gentleman from Vienna with an umbrella inflicting his dreams upon me. I don’t have the dreams that he discusses in his books, I don’t see umbrellas in my dreams or balloons.”

July 1962: Sue Lyon, the young actress selected to play the title role in Stanley Kubrick’s ‘Lolita’, bites her thumb in concentration.

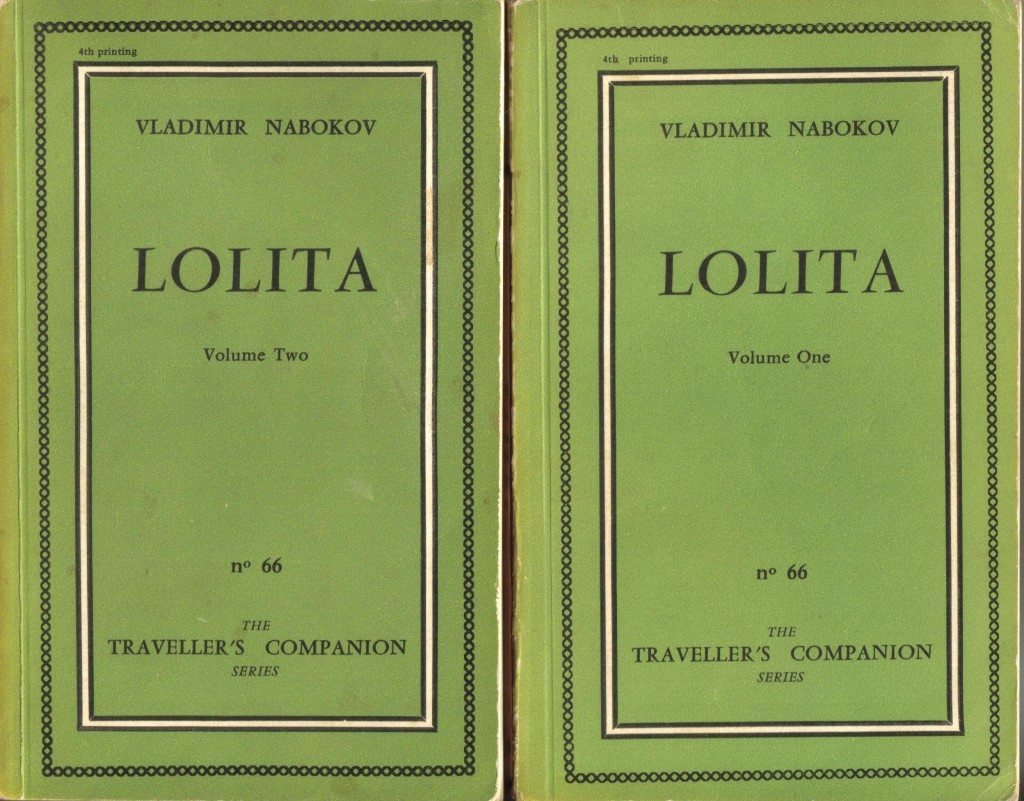

In the TV show USA: The Novel, Vladimir Nabokov comments on different covers of his 1955 novel Lolita, the story of a “vain and cruel wretch’s” obsession with an adolescent girl. It’s the book many think perverted. Many others consider it wonderful and elegant.

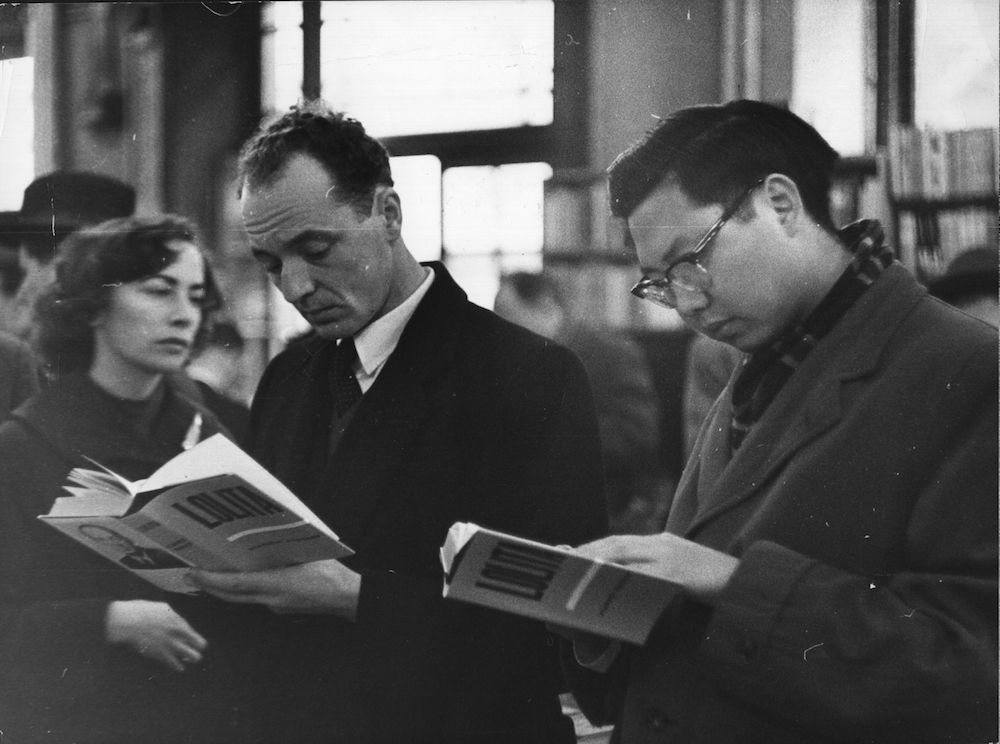

Would a grown man read Lolita on public transport? Would it require a blank cover, one not featuring the pouting Sue Lyons, star of the book’s film version? Is it ok to read about Nabokov’s “nymphet” (a word he coined himself and used in other books to describe young and fleeting figments or his imagination as seen in Lolita and his novels Transparent Things, Ada or Ardor: A Family Chronicle, The Original of Laura)?

Nabokov liked riddles. He created one that endures. Why is Lolita such a problem 60 years after its publication? What Martin Amis calls Nabokov’s “little girl thing” makes reading his Lolita “embarrassingly conspicuous”.

In the video below, Nabokov enjoys the diverse illustrations to his greatest work. “I am a slave of images,” says Nabokov through the philosopher John Krug in Bend Sinister. The author told publishers:

“I want pure colors, melting clouds, accurately drawn details, a sunburst above a receding road with the light reflected in furrows and ruts, after rain. And no girls. … Who would be capable of creating a romantic, delicately drawn, non-Freudian and non-juvenile, picture for LOLITA (a dissolving remoteness, a soft American landscape, a nostalgic highway – that sort of thing)? There is one subject which I am emphatically opposed to: any kind of representation of a little girl.”

Book covers can influence how casual readers browsing for titles views the text.

7th November 1959: Customers at a London bookshop read the controversial bestseller ‘Lolita’ by Vladimir Nabokov.

Freud’s view mattered, at least to readers and publishers it did.

On February 3, 1954, Nabokov wrote to James Laughlin, founder of publishers New Directions. “Would you be interested in publishing a timebomb that I have just finished putting together?” asked the author. “It is a novel of 459 typewritten pages.”

Nabokov was aware of his book’s power to subvert and prick convention.

In December 1953, one publishing editor reviewed the Lolita manuscript thus:

“It is overwhelmingly nauseating, even to an enlightened Freudian. To the public, it will be revolting. It will not sell, and will do immeasurable harm to a growing reputation… I recommend that it be buried under a stone for a thousand years.”

Or wrapped in a plain brown wrapper and read in solitude.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.