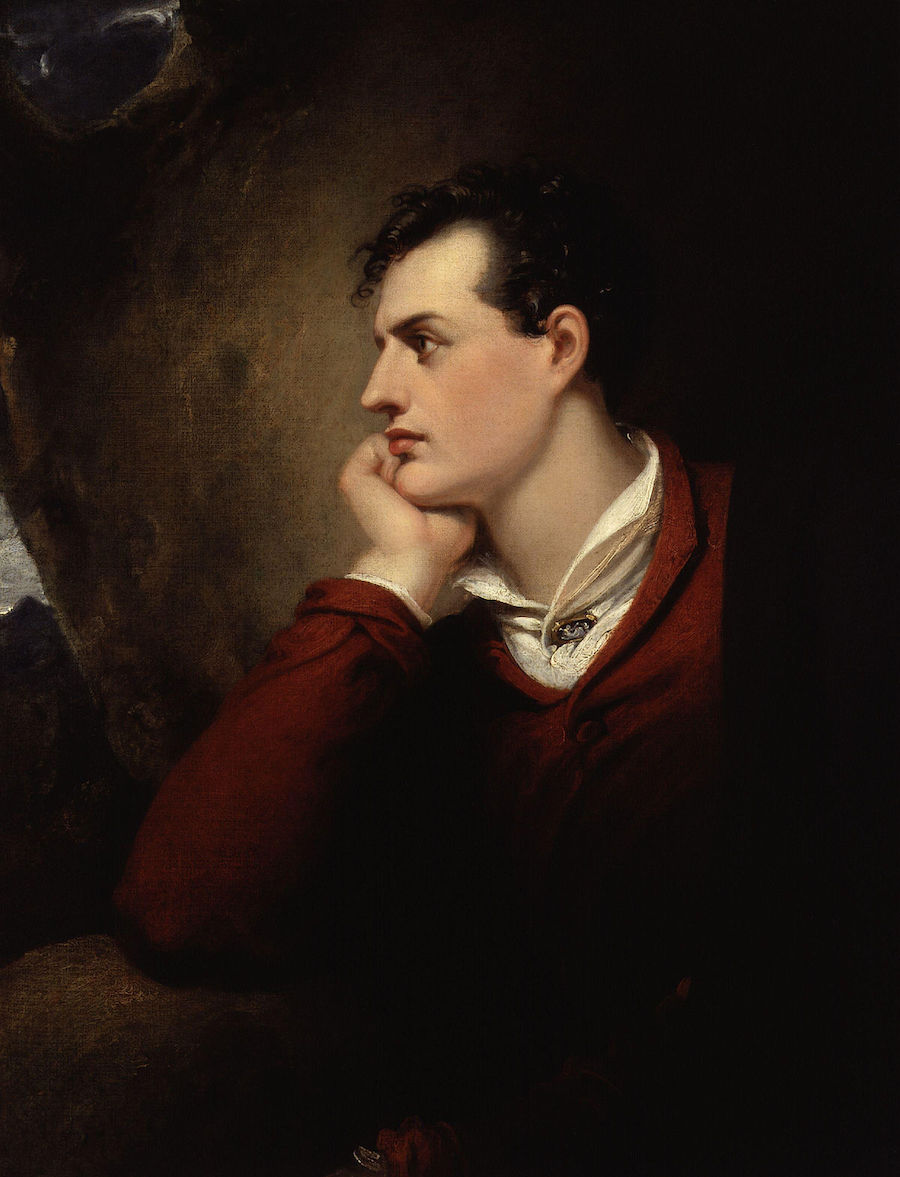

Doubt weakens the strongest faith. For some time, the Reverend Canon Barber, vicar of Hucknall parish, was concerned the body in the crypt of his church of St. Mary Magdalene, Nottinghamshire, was not that of the poet Lord Byron but possibly an impostor. Who else it could have been, he was not quite sure, but he often wondered if, in fact, there was a body in the crypt at all. It was a small doubt grown large from questions asked by the many visitors to the parish, who came to pay pilgrimage at the poet’s (supposed) final resting place. The question which troubled him most: But how do you know he’s buried here?

When Byron died of fever at the age of 36 in Missolonghi, Greece, on 19th April 1826, his body was opened up by five physicians and his brain and internal organs removed. What they were looking for, one has to wonder, but it is believed the Greeks wanted a part of their hero poet to be kept in their country. Byron’s final adventure brought him to Greece with the intention of liberating the country from their Ottoman rulers. The thought of having a tangible symbol of the poet would be enough to inspire the Greeks to fight on.

Back in Blighty, there was controversy over where the poet was to be buried. Westminster Abbey refused on ground’s of Byron’s “questionable morality.” After several weeks of negotiations, the corpse was eventually shipped back to England, embalmed in a vat of brand, for burial at the Church of St. Mary Magdalene.

Early in 1938, Canon Barber confided in the church warden A. E. Houldsworth about his misgivings and expressed his intention to examine the Byron vault and “clear up all doubts as to the Poet’s burial place and compile a record of the contents of the vault.”

Canon Barber wrote to his local member of Parliament requesting permission from the Home Office to open the crypt. He also wrote to the surviving Lord Byron, who was then Vicar of Thrumpton, asking for permission to enter the family vault. The Vicar gave his agreement and “expressed his fervent hope that great family treasure would be discovered with his ancestors and returned to him.”

At four o’clock on the afternoon of 15th June 1938, the doors to St. Mary Magdalene were locked. Inside, around forty people waited expectantly for the opening of the Byron vault. According to notes written by Houldsworth, among those in attendance were:

Rev. Canon Barber & his wife

Mr Seymour Cocks MP

N. M. Lane, diocesan surveyor

Mr Holland Walker

Capt & Mrs McCraith

Dr Llewellyn

Mr & Mrs G. L. Willis (vicar’s warden)

Mr & Mrs c. G. Campbell banker

Mr Claude Bullock, photographer

Mr Geoffrey Johnstone

Mr Jim Bettridge (church fireman)

The others were not known to Houldsworth.

By six-thirty, masons were able to remove the large slab above the vault. Dr. Llewellyn used a miner’s safety to be lowered into the opening to test the air. The first view of the vault revealed it be a surprisingly small area with two ornate coffins.

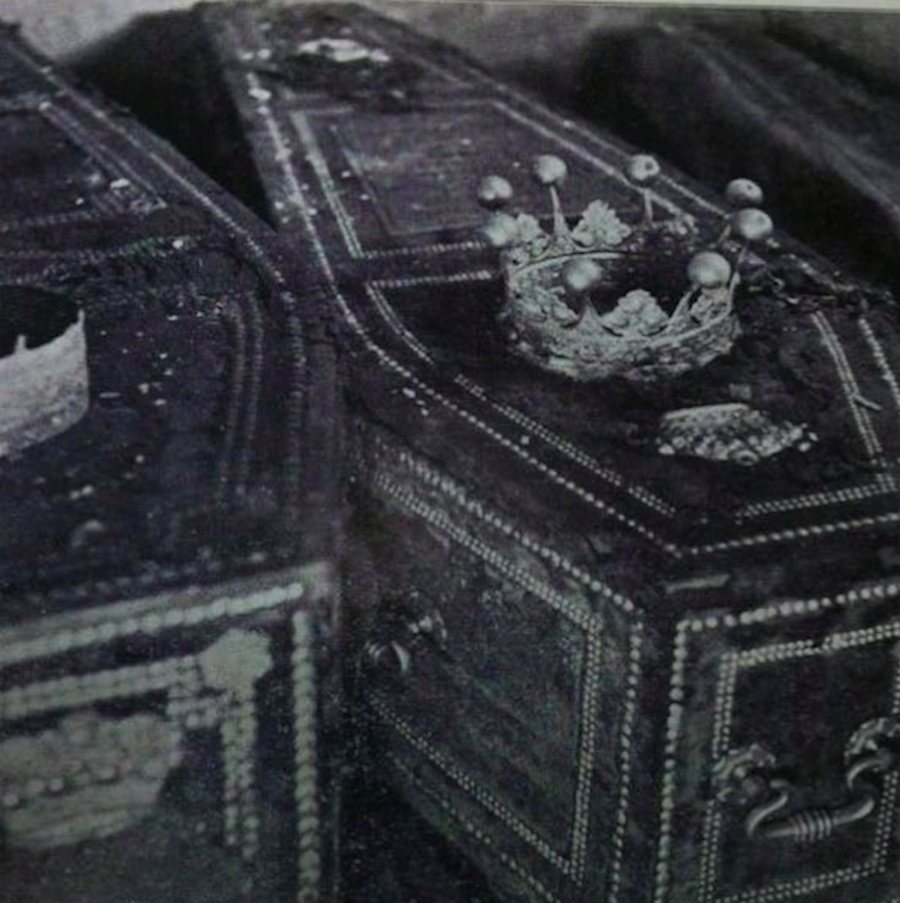

From a distant view the two coffins appeared to be in excellent condition. They were each surmounted by a coronet… The coronet on the centre coffin bore six orbs on long stems, but the other coronet had apparently been robbed of the silver orbs which had originally been fixed on short stems close to the rim.

The coffins were covered with purple velvet, now much faded, and some of the handles had been removed. A closer examination revealed the centre coffin to be that of Byron’s daughter Augusta Ada, Lady Lovelace.

At the foot of the staircase, resting on a child’s lead coffin was a casket which, according to the inscription on the wooden lid and on the casket inside, contained the heart and brains of Lord Noel Byron. The vault also contained six other lead shells all in a considerable state of dissolution–the bottom coffins in the tiers being crushed almost flat by the immense weight above them.

Byron’s coffin was missing its nameplate, brass ornaments, and velvet covering. It looked solid but was soft and spongy to the touch. Houldsworth called on Johnstone and Bettridge to help raise the lid. Inside was a lead shell. When this was removed, another wooden coffin was visible inside.

After raising this we were able to see Lord Byron’s body which was in an excellent state of preservation. No decomposition had taken place and the head, torso and limbs were quite solid. The only parts skeletonised were the forearms, hands, lower shins, ankles and feet, though his right foot was not seen in the coffin. The hair on his head, body and limbs was intact, though grey. His sexual organ shewed quite abnormal development. There was a hole in his breast and at the back of his head, where his heart and brains had been removed. These are placed in a large urn near the coffin. The manufacture, ornaments and furnishings of the urn is identical with that of the coffin. The sculptured medallion on the church chancel wall is an excellent representation of Lord Byron as he still appeared in 1938.

Detail from a lithograph of Lord Byron and Marianna Segati—and the wife of his landlord in Italy, and his lover

It’s been claimed by some that Byron had an enormous erection. In the 1970s, Houldsworth told a local newspaper that Byron’s penis was as big and as long as “a pony’s.” It was noted the men in attendance took turns in entering the vault to view Byron’s body before returning (no doubt in shock and awe) to the church above. There is no mention as to how the women responded. Houldsworth also later wrote to one of Byron’s biographers, Elizabeth Longford, that the poet’s missing lower leg–the one with the club foot–was located at the bottom of the coffin.

Unfortunately, the photographer present refused to take any pictures of Byron’s corpse for fear of sacrilege–well, that was his excuse. However, he did take a picture of the two coffins which was featured in the Rev. Canon Barber’s book Byron–and Where he is Buried in 1939.

Detail from a pencil portrait of Lord Byron (undated, ca. 1820s), signed “M.B.,” a copy after G.H. Harlow. New York Public Library

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.