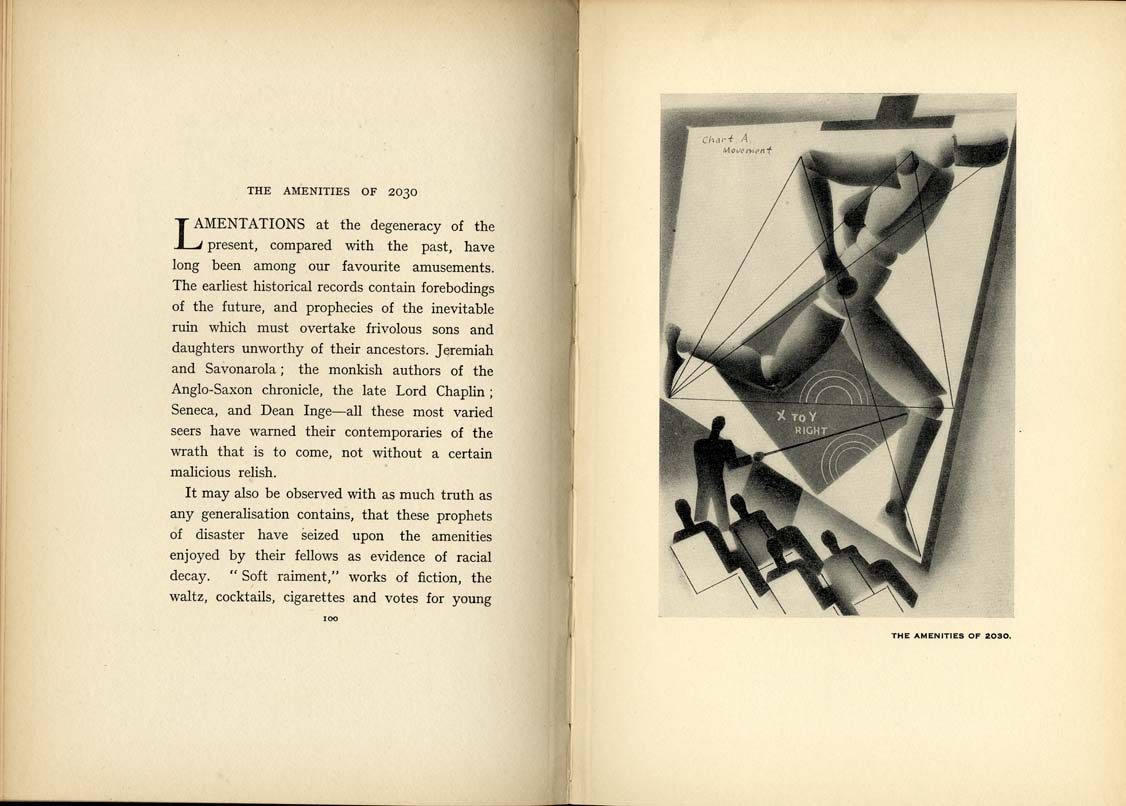

“If the next century is tranquil and prosperous, life in 2030 will be adorned by cultured and urbane amenities in excess of the pleasant accompaniments which our contemporary civilisation can exhibit.”

– The World in 2030

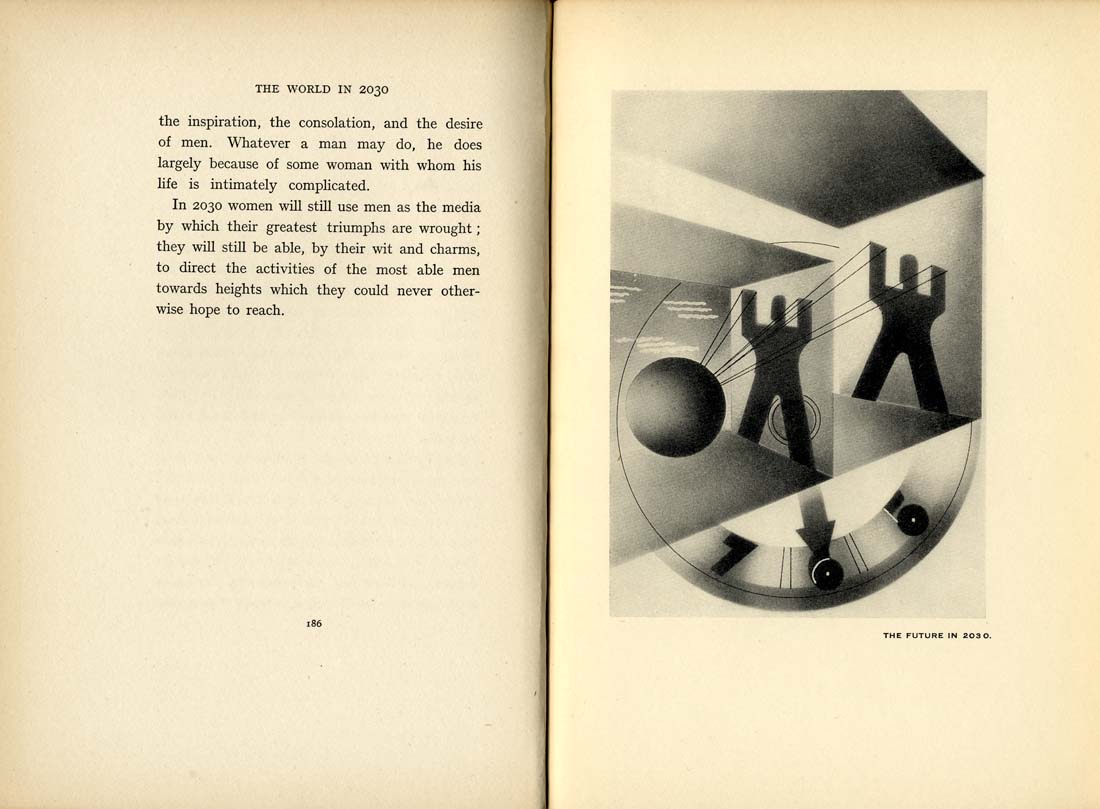

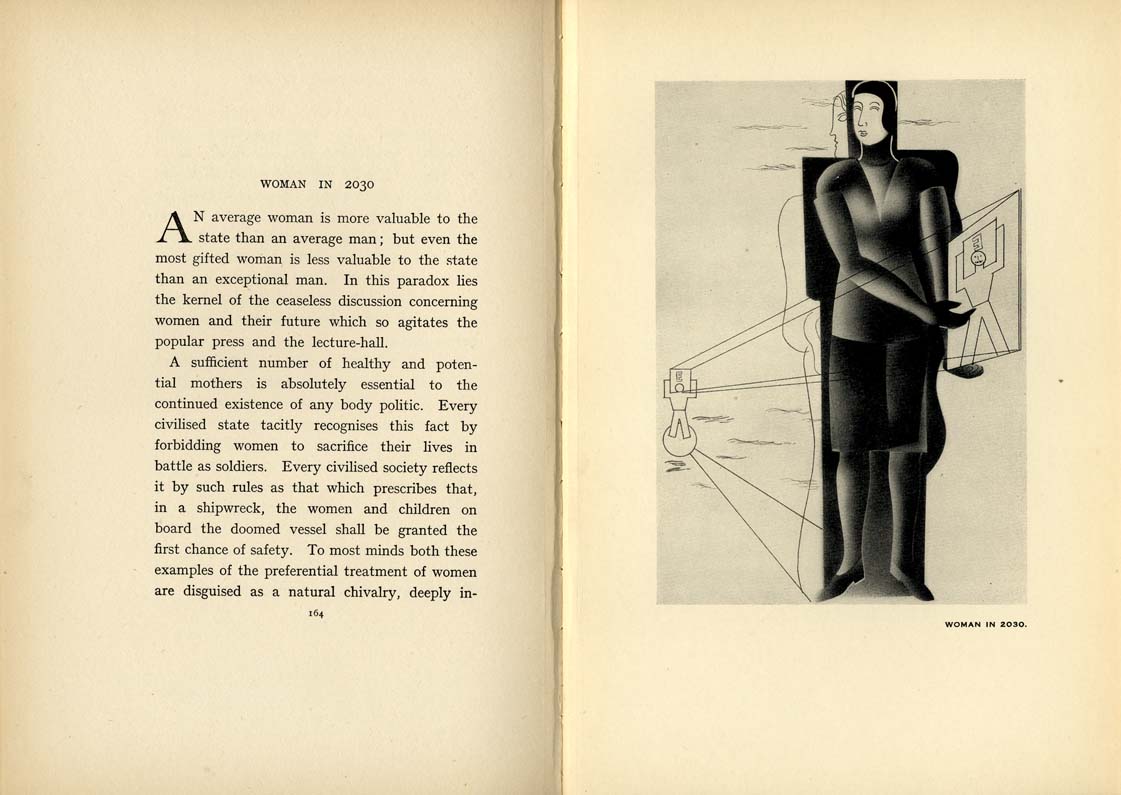

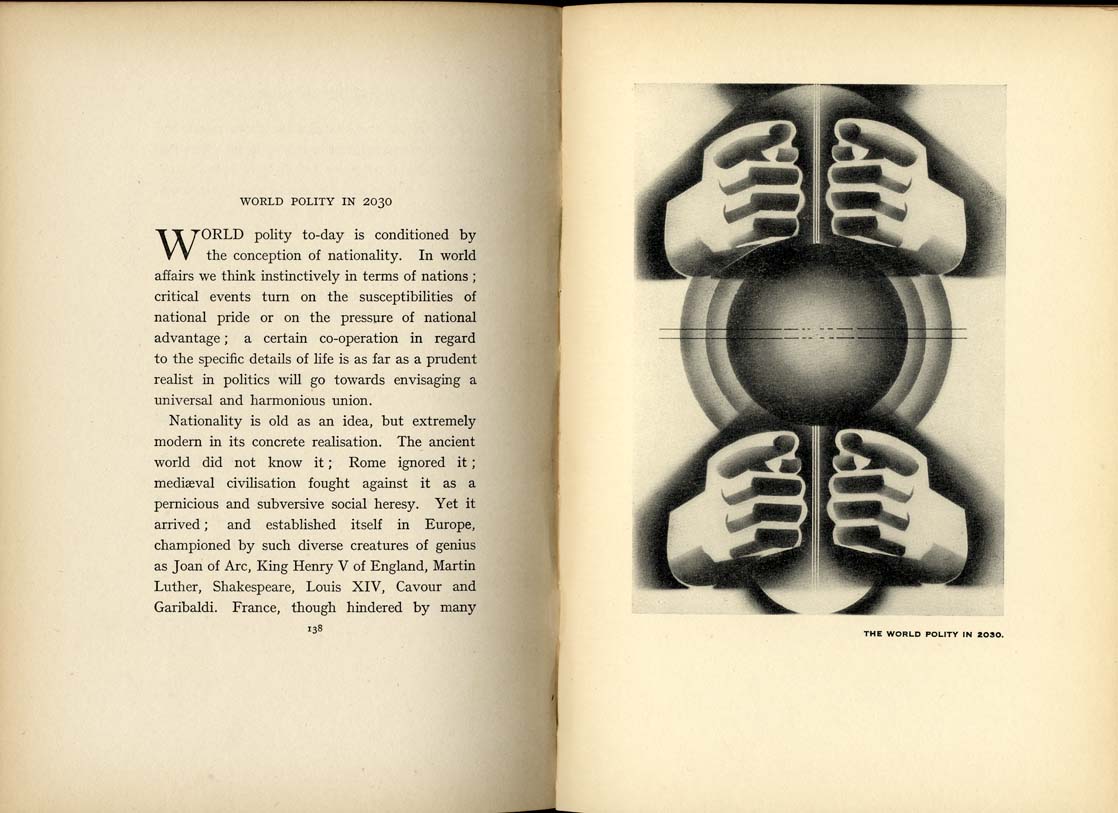

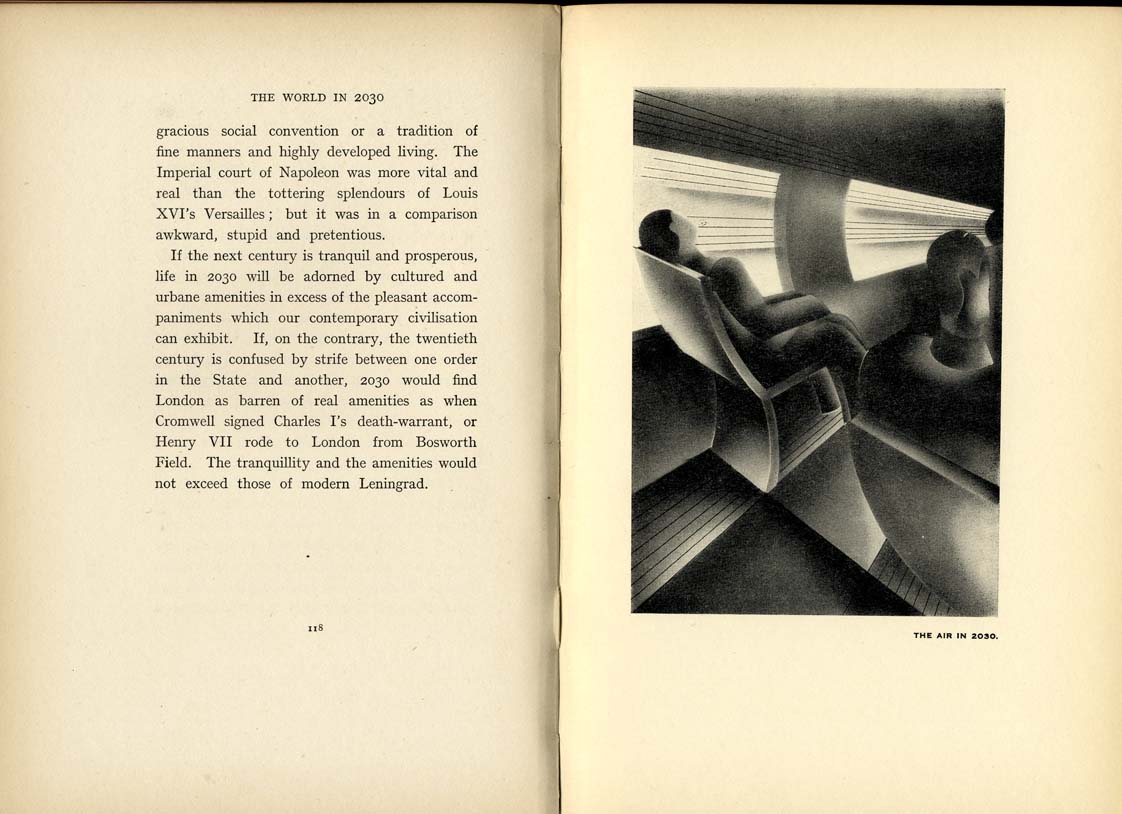

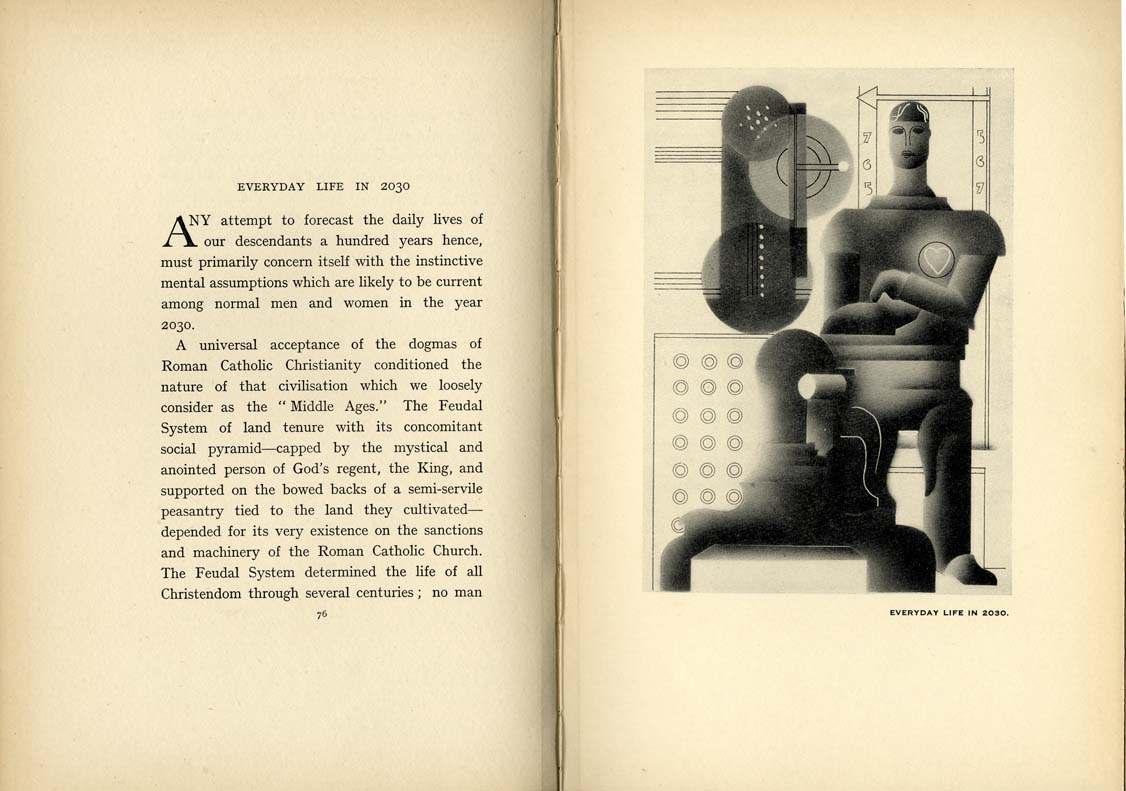

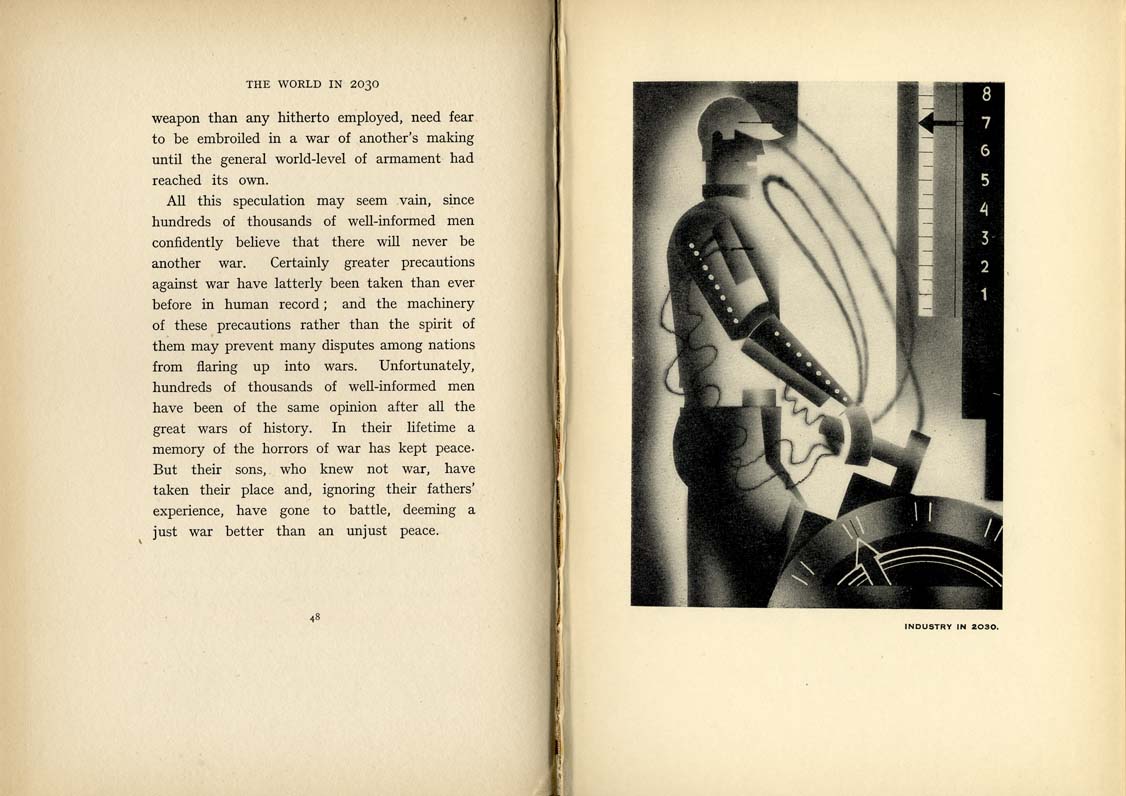

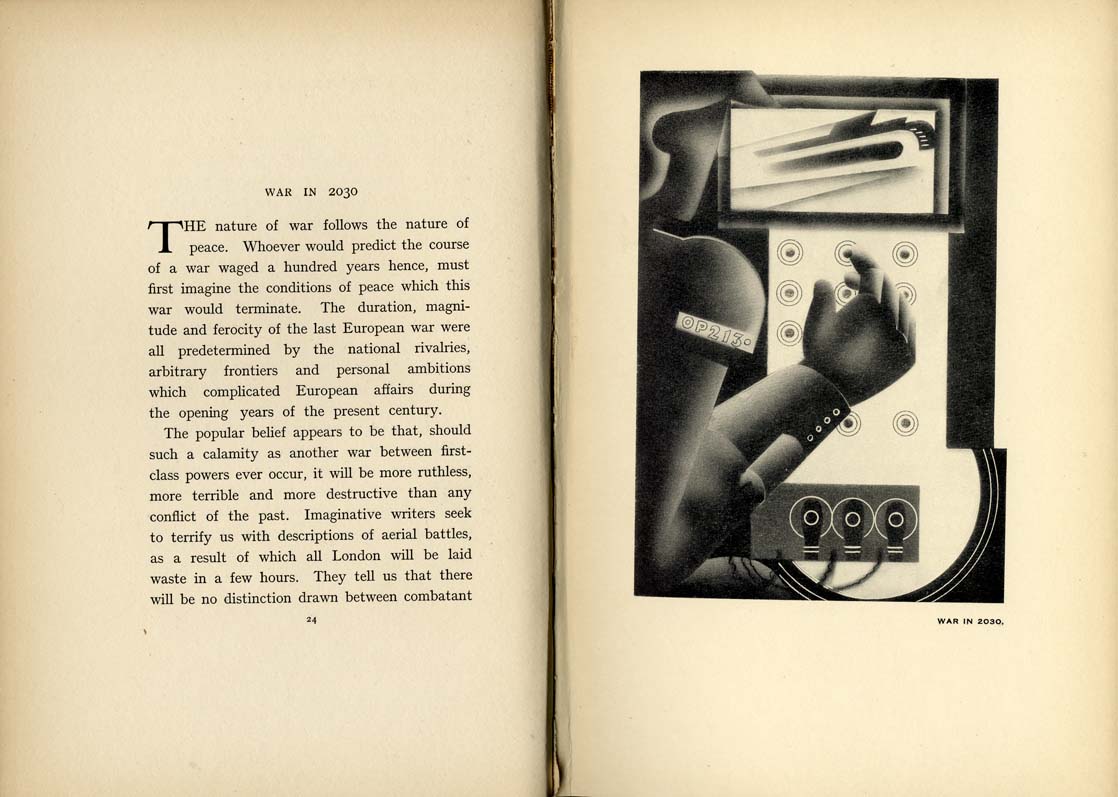

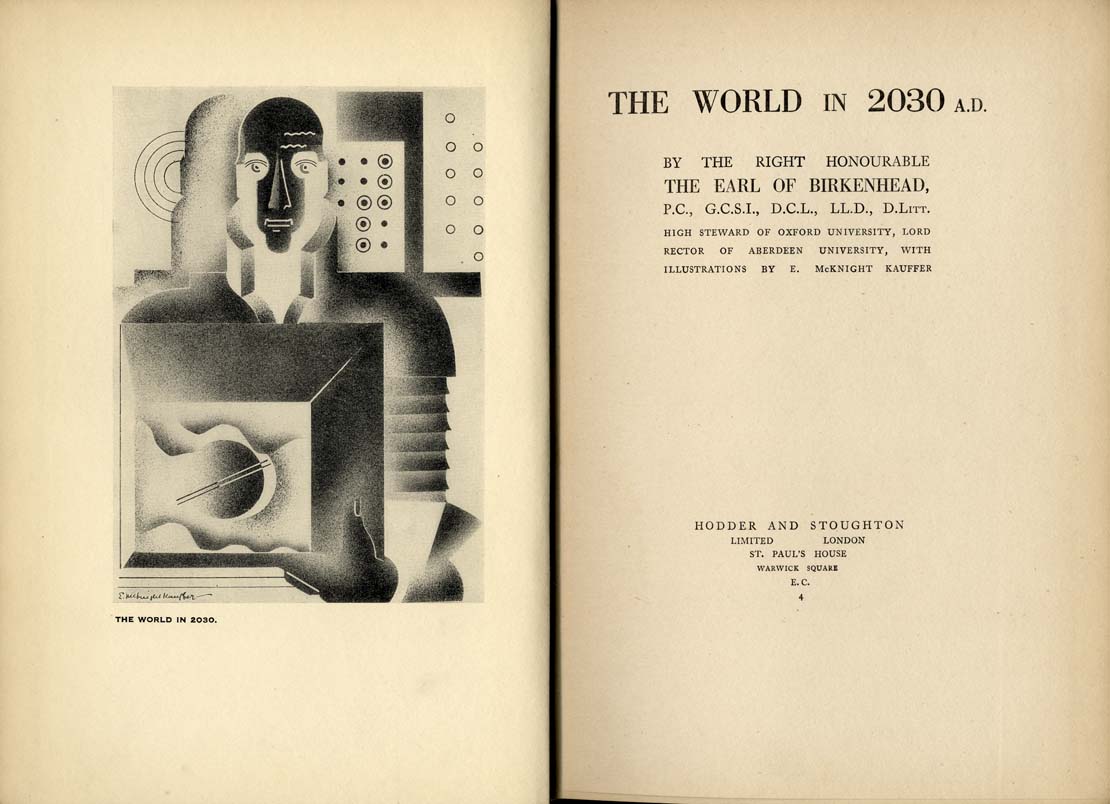

E McKnight Kauffer used an airbrush to produce the robotic steel forms for the 9 illustrations he contributed to The World in 2030 A.D.

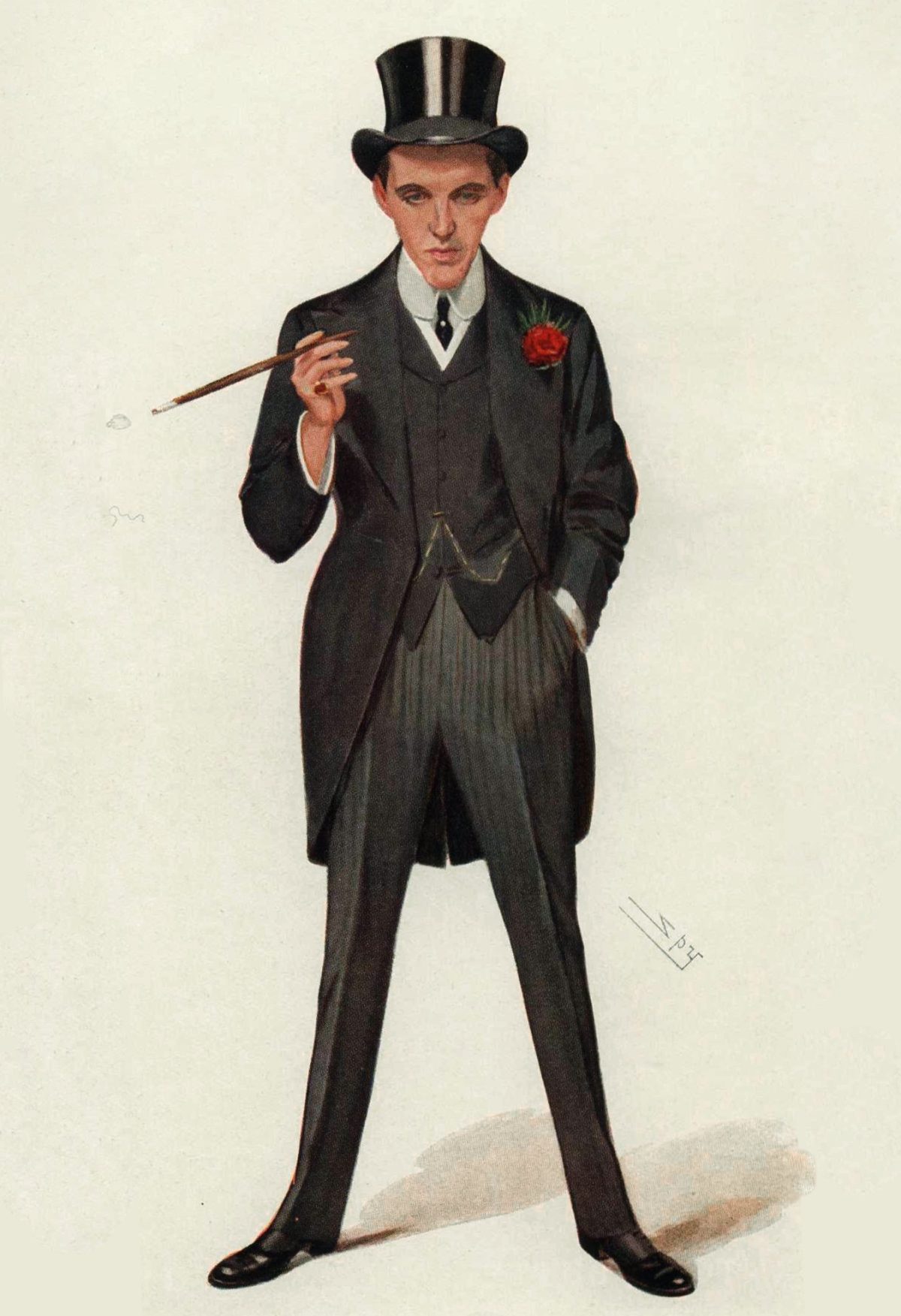

The book was published in 1930, the year its author, conservative politician FE Smith (Earl of Birkenhead) died. Smith was a British Cabinet minister, a former Lord Chancellor, a leading lawyer and a friend of Winston Churchill.

The world he described is calmer and more rational with humane warfare, as opposed to 1930. I think it’s safe to conclude that the illustrations are the highlight of this work. He was “fairly certain” by 2030 of “the discovery of cures for such scourges as cancer”.

Eugenics was at the time popular. He claimed a clever young man would “consider his fiancee’s hereditary complexion before proposing marriage”. In return, “the young woman of that day will refuse him because he has inherited a gene from his father which will predispose their children to quarrelsomeness”.

TV would mean that cricket buffs would will be able to follow the fortunes of an English eleven through the days (or weeks) of an Australian Test match”.

Automation would mean a “gradual contraction” of hours worked. By 2030 it was likely the “average week of the factory hand will consist of 16 or perhaps 24 hours”, which no working man or woman could possibly “grudge”. Work would be “supremely easy and supremely dull”. But: “As wealth increases, we shall all be able to ride to hounds.”

Tally ho to the rosy-fingered dawn of tomorrow!

It is certain, therefore, that the ordinary household arrangements which suffice to-day, will prove inadequate for the needs of 2030. In spite of the myriad “ labour-saving devices’’ which will doubtless have multiplied by that date, and will have converted the English domestic interior into the semblance of a machine shop, many married couples will find housekeeping beyond their powers. Perhaps they may find refuge in large communal establishments, equipped with private bed rooms and studies, but sharing refectories, libraries, music-rooms, lounges, nurseries and kitchens. The management of these synthesised homes may be undertaken by the large number of women who adorn every generation and who, to the eternal benefit of their friends and relations, find their greatest happiness in discharging the duties of housekeeper or nurse.

I do not believe that any amount of organised education can turn such women from domestic occupations and cares.

“Thus… the man of 2030 will set off for the weekend, after his work, in a small, swift aeroplane, as reliable and cheap as the motor-car on which we depend today,” he wrote. The idea of a weekend would be different in a world where people only worked two hours a day or two full-time days, and transport would enable more adventurous time off. “Ski-ing parties in Greenland will be made up in London clubs on Saturday mornings and translated into action before the same evening.”

“By utilising some 50,000 tons of water, the amount displaced by a large liner, it would be possible to remove Ireland to the deeper portion of the Atlantic Ocean.”

In 2030 science will make the city a self-supporting unit, and Britain a land of laboratories capable of feeding no matter how many millions of mouths without importing a ton of foodstuffs. Many will bewail such a prospect, for they insist that a flourishing agricultural peasantry is the only sound basis of any political life. It will be necessary when agriculture goes into irrevocable decay, to plan the evolutions of a stable industrial society. Such an undertaking should not he beyond human wit. The agricultural basis of society, which has existed for so many centuries, was itself evolved from nomads and savages. To reconcile such folk with the peaceful static life of the husbandman needed a far more violent adjustment than will be necessary to urbanise the descendants of the world’s present agriculturists.

“By utilising tidal energy to any large extent, we should diminish the speed of the earth’s rotation,” said Smith. If tidal energy was overused, a “48-hour day is a possibility in the far future.”

“The commanders of tank forces will be carried in the air above their commands and thus will be able to watch the course of operations and control their progress by wireless telephony.” Or this could happen in a “distant control room”, possibly underground. Birkenhead said this would make war “more humane”.

To those who choose to stay at home, rather than depart by air for a remote resort, 2030 will offer attractions far in advance of anything possible to-day. The development of broad casting and television will enable a family, gathered round its own atomically radiant hearth, to watch and listen to a variety of spectacles.

On a screen let into the wall of the room where they are gathered, plays will be projected stereo-scopically in full natural colours. From a concealed loud speaker the voices of the actors will emerge as from their owners’ mouths—not, like the “ talkies ” of to-day, as if muttered through a lamp-glass darkly. It will be possible to create in a private house the exact illusion of physical presence at a stage performance hundreds of miles away.

By this means everyone will be enabled to assist at performances by the most gifted actors and actresses of the day. Any piece can be revived “for one night only” at a moment’s notice. In this case, a perfect talking film recorded on a previous occasion will be sent out through the transmitting apparatus

Caricature of F.E. Smith (later Earl of Birkenhead). Caption reads “A Successful First Speech (“Moab is my Washpot”)”. (This refers to Psalm 108). Vanity Fair, 16 January 1907.

Via: E McKnight Kauffer

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.