“In countries which do not enjoy Mediterranean sunshine idleness is more difficult, and a great public propaganda will be required to inaugurate it. I hope that after reading the following pages the leaders of the Y.M.C.A. will start a campaign to induce good young men to do nothing. If so, I shall not have lived in vain.”

— Bertrand Russell

European leisure culture has birthed many an expat novel, Italian cinematic romp, acid-soaked rave, and middle-aged sexcapade. Aside from pumping cash into the hotel, nightlife, and café sectors, most Europeans don’t do much in the way of commerce while on vacations. This can seem extravagant to outsiders. The “image of a casual Western European work ethic tends to be viewed with just short of scorn by the world’s other wealthy economies,” Katrin Bennhold writes at The New York Times. It’s a longstanding prejudice exemplified in jokes, such as that told by Bertrand Russell in 1932 essay “In Praise of Idleness.”

“Every one knows the story of the traveler in Naples who saw twelve beggars lying in the sun (it was before the days of Mussolini), and offered a lira to the laziest of them,” says Russell. “Eleven of them jumped to claim it, so he gave it to the twelfth.” The philosopher turns the unflattering stereotype on its head. “I think,” he argues, “there is far too much work done in the world, that immense harm is caused by the belief that work is virtuous.” The origin of that hallowed belief is the firm conviction that everything, and everyone, must turn a profit, usually for the benefit of someone else.

Navigating uneasily between the rapaciousness of an unregulated free market and a dictatorship of the proletariat, the various market economies that emerged in postwar Europe have supported, fostered, and democratized leisure traditions once available only to an elite. Bemused economists argue amongst themselves whether different attitudes towards work come down to culture or economics, but the answer is both. Slower growth in Europe “reflects policy choices that have tended to put a premium on leisure and equality at the expense of greater wealth.”

If well-subsidized leisure cultures have been used as a bulwark against communism, they are also vulnerable to fascism, as Russell suggests in his passing reference to Mussolini. For photographer Sergio Purtell, that threat came in the form of U.S.-backed military dictator Augusto Pinochet, installed in Chile with the aid of the C.I.A. and Milton Friedman’s neoliberal acolytes. As the socialist government of Salvador Allende fell, Purtell fled the country. “I left for the US in 1973—by myself,” he tells It’s Nice That. “I was 18. I worked menial jobs and put myself through school. He eventually earned a BFA from the Rhode Island School of Design and an MFA from Yale.

Rather than sit at a desk and do design work to pay off his student loans, Purtell decided he needed to travel. “Every summer from the late 1970s through the mid 1980s I would buy an inexpensive round-trip ticket from New York to London, and from there get a Eurail pass. Travelling cheaply, I could move freely around Europe, renting rooms in seedy little hotels, usually right next to the train station. Sometimes I even slept right there on the station floor.”

Wandering made sense, he says. “My father had arrived in Chile in 1954, riding a Harley Davidson…. I left Chile for the US… fleeing an imminent dictatorship.” In Purtell’s travels, he seemed to find what he didn’t know he’d been missing.

I was immediately reminded of my life in Santiago: the mannerisms, the customs, the architecture, the relaxed attitude towards life, the mornings in cafes nursing a cup for as long as one wanted, the afternoons passed lounging by the cool of a fountain, and finishing the day at the local bar with a glass of wine.

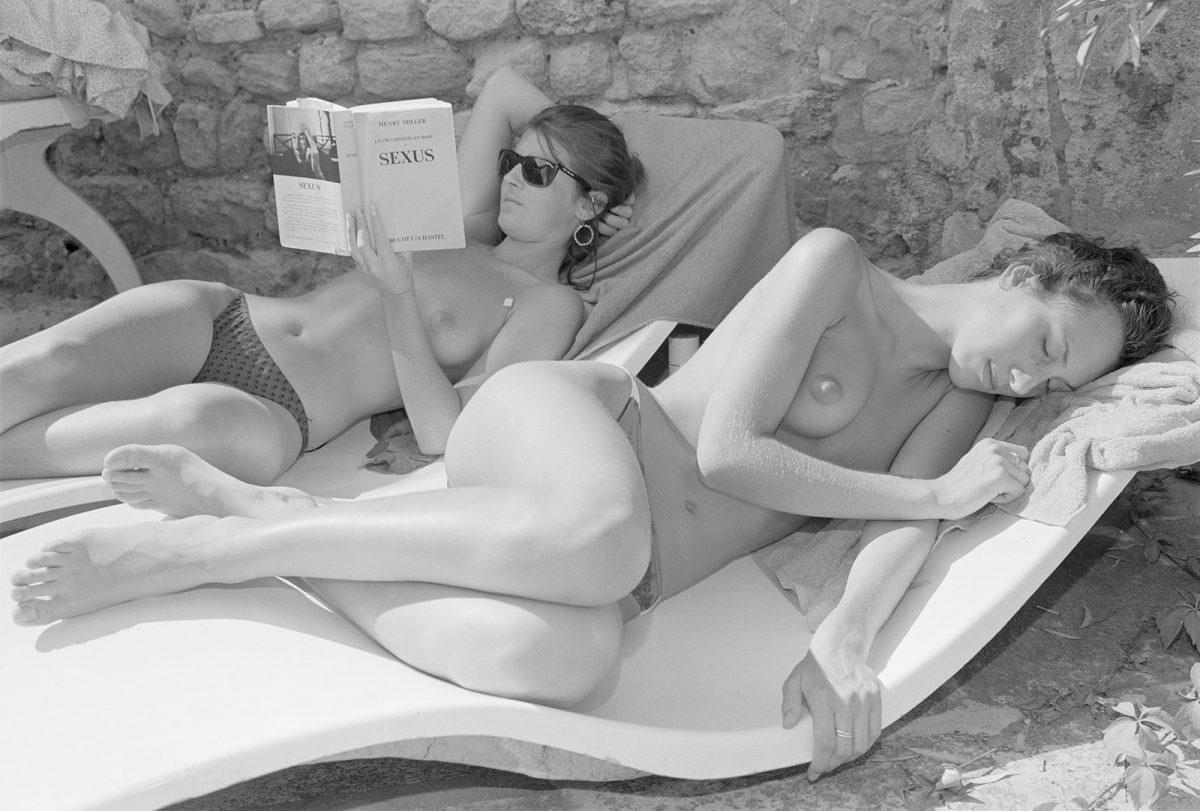

I studied the small gestures, the unruliness of leisure…. I was allowed to record lives that seemed familiar to me even though I had just arrived.

Collecting these photographs decades later, Purtell preferred to look back with nostalgia and forward with hope, and “take politics out of the picture” when his publisher suggested the title Moral Europe. Instead he chose Love’s Labour, in reference to the early Shakespeare comedy in which, ironically, the main characters forswear sexual pleasure. It is also, he says, a play “where love is the unifying force.” Love, that is, in the end, of leisure.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.