Jessie Matthews in ‘FIRST A GIRL’, 1935

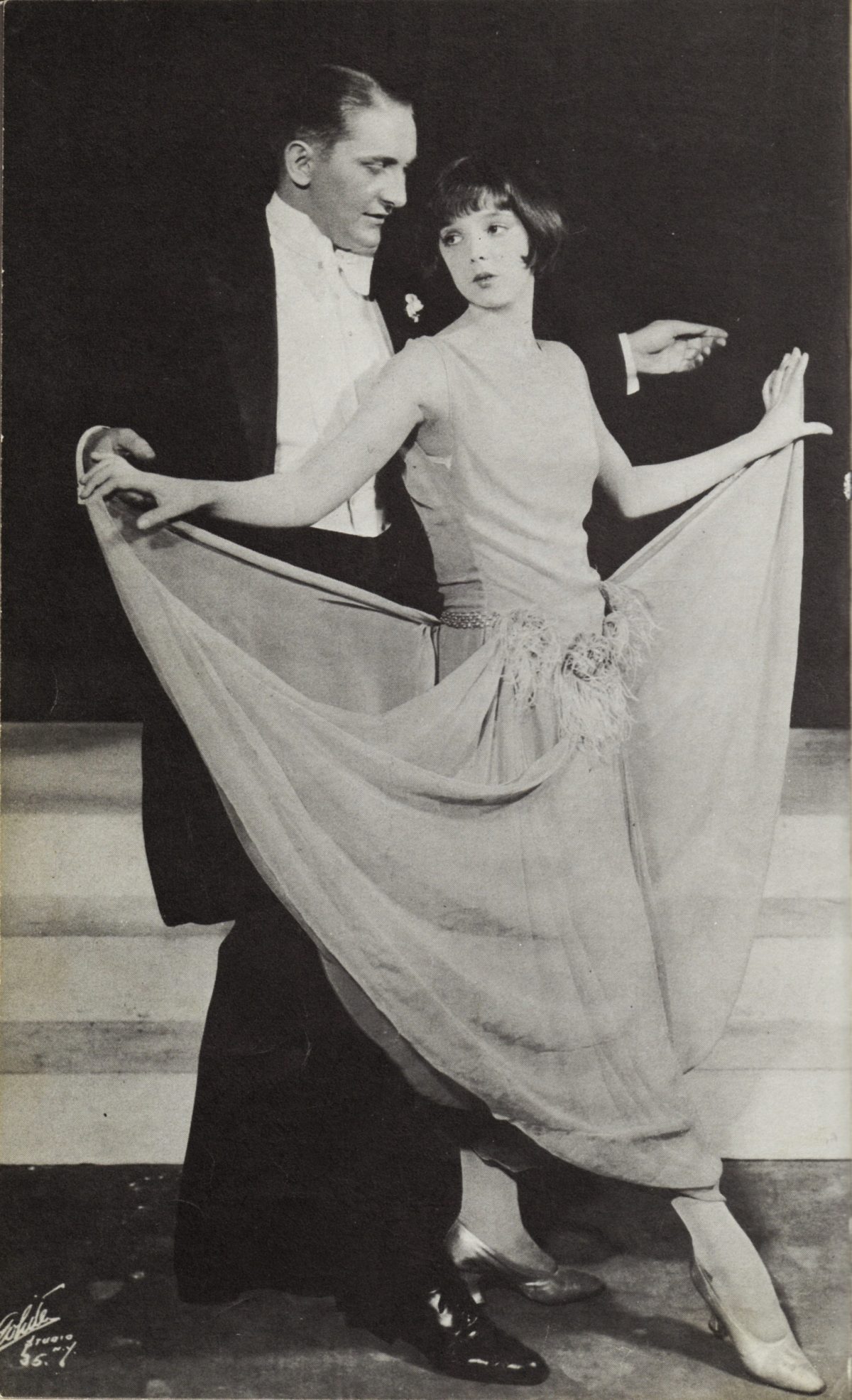

Late in 1927, Noël Coward was so upset that he made plans to leave the country. After a run of golden successes, the twenty-nine-year-old writer had just suffered two humiliating flops, the last of which was Sirocco, a play he had originally written in New York in 1921. The opening night at the Daly’s Theatre was nothing less than a catastrophe. The trouble started during the initial love scene between Ivor Novello, perhaps a little camp for the Italian ladies’ man he was meant to be playing, and a beautiful but inexperienced Canadian actress called Frances ‘Bunny’ Doble. Noël once said of Novello, ‘The two most beautiful things in the world are Ivor’s profile and my mind.’ But when Novello and Doble started kissing, however, there was no chemistry at all, and the audience began to make loud sucking sounds. When the couple started to roll on the floor together, supposedly in the throes of passion, the gallery broke into fits of laughter…

Frances Doble and Ivor Novello in Sirocco

Essentially Sirocco was a weak play and neither of the principal actors had enough stage presence for this not to matter. In theatrical circles the word ‘Sirocco’ quickly became a synonym for disaster: ‘How did the opening night go?’ ‘An absolute Sirocco, old boy!’

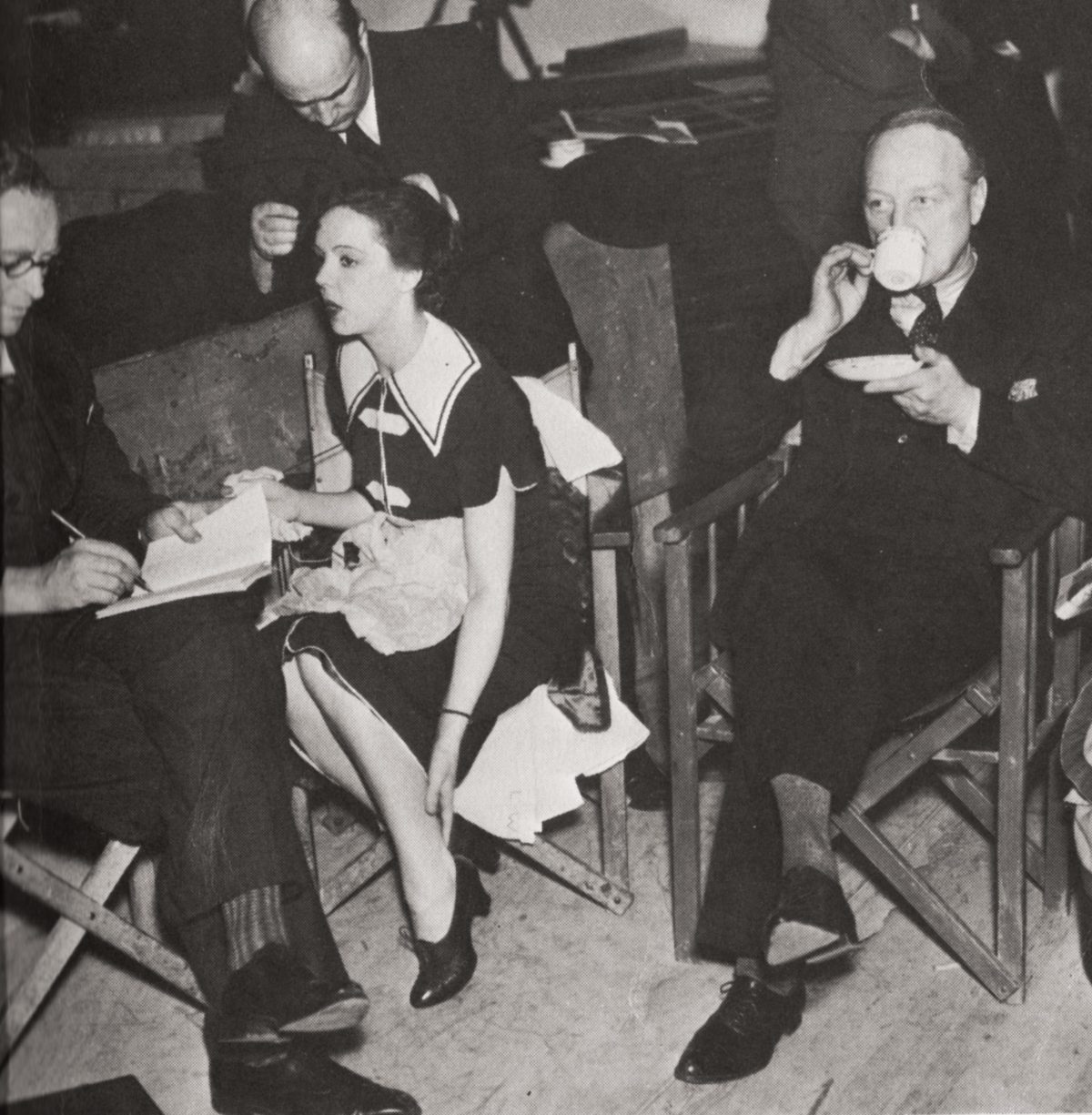

After the Sirocco debacle the theatre impresario C. B. Cochran soothed Coward by saying that only he had the talent to write the new revue he had commissioned. Cochran knew that after the two recent failures Coward, as a working partner, would be more malleable, at least for a short while. The subsequent rehearsals for This Year of Grace, at this point still known as Cochran’s Revue of 1928, took place in the Poland Rooms on Poland Street in Soho. Noël Coward once described the ‘dusty and dreary’ room:

[It contained] a tinny piano, too many chairs, a few mottled looking glasses, sometimes a practice bar and always a pervasive smell of last week’s cooking. Here rows of chorus girls in practice dress beat out laboriously the rhythms dictated by the dance producer. The chairs all round the room are festooned with handbags, hats, coats, sandwiches, apples, oranges, shoes, stockings and bits of fur. It is all very depressing, especially at night in the harsh glare of unshaded electric bulbs.

Jessie Matthews aged 18 Charlot’s Revue of 1925

According to Jessie Matthews, the young female lead in the revue, Coward was an exacting and strict director. She once described meeting Coward for the first time as he entered the rehearsal room: ‘He walked in, tall and elegantly dressed and immediately terrified me. He was obviously everything I was not. Highly sophisticated, articulate and completely sure of himself.’

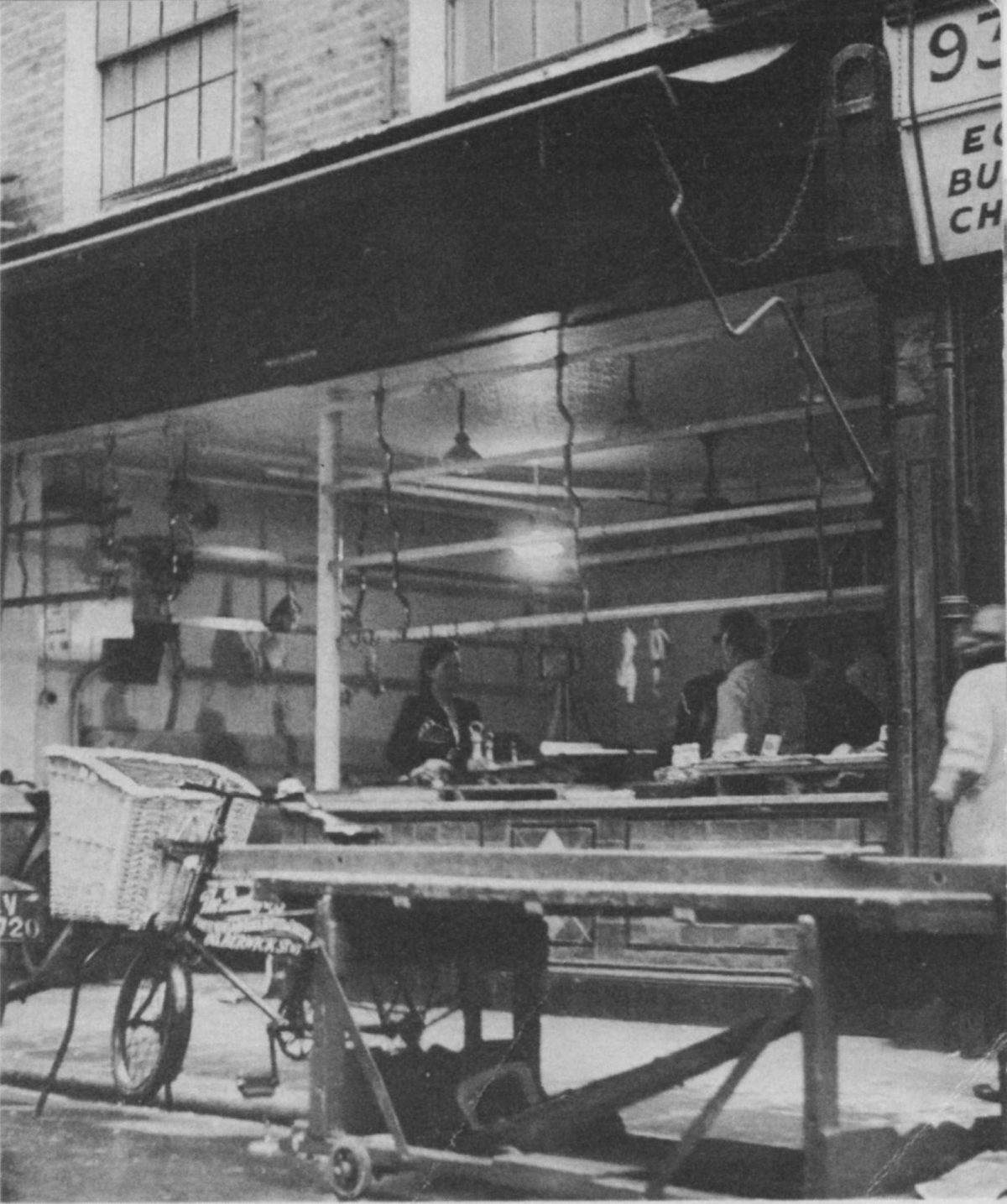

Today, except for the oldest amongst us, and the blue plaque on the wall of the Blue Posts pub on the corner of Berwick Street and Broadwick Street, the stage and film star Jessie Matthews has almost been forgotten. Once, however, she was one of the most famous women in the country. In 1936 it was reported that in Britain she was more popular than Shirley Temple, Bing Crosby and Gary Cooper, and during the 1930s she was always voted one of Britain’s favourite film-stars. Sixth of sixteen children (only eleven survived), Jessie was born on 11 March 1907 in a small, cramped and overcrowded flat above a butcher’s shop in Soho’s Berwick Street. Her father was a costermonger in the market for which the street is, just about, still famous.

Butchers shop 94 Berwick Street Jessie Mathews was born above the shop

His stall was always outside the Blue Posts pub and sold oranges, apples and pears arranged in pyramids. At Christmas, with the market lit by yellow paraffin flares, he had a toy stall selling wooden soldiers, spinning tops and skipping ropes. The family weren’t long at Berwick Street (the butcher wanted his flat back for his recently married son) but after a brief sojourn in Camden, they returned to Soho and lived in a small flat at number 9 William and Mary Yard on the north-west side of Little Pulteney Street. The yard contained stables and sheds that overnight stored the stalls and vans from the nearby Berwick Street market. They also housed the horses used by the local tradesmen to transport their stock from Covent Garden each morning.

Jessie Matthews was one of a class of sixty at the Pulteney LCC School for Girls on Peter Street, just around the corner from the cinema and William and Mary Yard. During a childhood she once described succinctly as ‘three or four in a bed, bread and scrape for supper some nights, and a swipe from Dad if we got in his way’, she started to train as a dancer. When she was ten her mother bought her the cheapest available ballet shoes from the theatrical shoe shop on the corner of Dean Street and Old Compton Street, and not long after Jessie performed in a show called Bluebell in Fairyland at the Metropolitan on the Edgware Road. The following year, as principal child dancer and billed as ‘Little Jessie Matthews’, she danced in Dick Whittington at the Kennington Theatre. As a teenager, with intensive elocution lessons from her sister Rosie to remove her natural cockney accent, she auditioned for one of André Charlot’s famous revues. Three decades later he still remembered that day:

Girl after girl had stepped forward, sung and said her little pieces, answered a few questions, and stepped back again. And suddenly one of them walked out of line to the front of the stage, leaned over, and said to me ‘What do you mean by keeping us waiting all this time? I want my lunch.’ I gasped. That I should be so addressed in my own theatre by a mere child, not yet fifteen, was beyond belief. Her eyes flashed and she stamped her little feet. ‘What a little spitfire,’ I said to myself.

Two years later she became one of C. B. Cochran’s high-kicking ‘Young Ladies’ and performed in the chorus of Music Box Revue in 1923. Within three years the saucer-eyed little spitfire was the lead in Charlot’s 1926 Revue – the Daily Chronicle said of her performance: ‘A triumph that would have turned the head of many an actress who has been 20 years on the stage’.

circa 1923: Comedy actress Jessie Matthews (1907 – 1981) as she appears in the Music Box Revue at the Palace Theatre, London.

Jessie Matthews’ co-star in This Year of Grace was to be the short and bespectacled comic actor Sonnie Hale – well known at the time not only for his comedic abilities on stage but also for being married, somewhat incongruously as far as looks were concerned, to the beautiful and popular West End actress Evelyn Laye. Hale was once described as looking like ‘some dim young man just starting on an obscure career in the City’, but although he wasn’t blessed with too much inherent talent, he was one of the best revue comic actors around and worked ceaselessly to perfect his singing, dancing and acting. Laye was a big star when they married in 1926, and she was earning more than £100 (approximately £5500 in 2017) a week and drove her own Lagonda car around town. Her parents disapproved of Hale and her mother told the bride-to-be on the actual wedding morning, ‘I hope you know what you’re doing,’ before saying gently but firmly, ‘Daddy and I won’t be coming on to the reception.’

A Room with a View…and you’ This Year of Grace London Pavilion 1928

Not long before the opening night of This Year of Grace, Evelyn Laye held a small supper party for her close friends at Soho’s Gargoyle Club – a recently opened private members’ club on the upper floors of 69 Dean Street (at the corner with Meard Street). Owned by the aristocratic socialite David Tennant, there was a ballroom, a bar, coffee room and drawing room with some of the interiors by Henri Matisse. It was reached by a rickety lift so small it was said that strangers became intimate friends by the time it reached the top floor. Laye’s guests that evening included the film actors Ruby Miller and a boyish twenty- four-year-old called Frank Lawton. Slightly late, and after a This Year of Grace rehearsal, Laye’s husband Sonnie Hale turned-up at the club accompanied by his charming co-star.

The Gargoyle Club was not a stone’s throw from the street where Jessie Matthews was born and brought up, but in some respects it was a million miles away. Evelyn Laye greeted Jessie warmly when she arrived at the Gargoyle, and although the two women had met at various theatrical parties they did not know each other well. Born Elsie Evelyn Lay, and from a young age known informally as ‘Boo’, Laye was six years older than Matthews and had been born in Russell Square in Bloomsbury. Her parents were both respected actors and her father had become a theatre manager, and also a musician and composer. While Jessie was still at Pulteney School, Evelyn made her first stage appearance in August 1915 at the Theatre Royal in Brighton as Nang-Ping in Mr. Wu. Sitting opposite each other

Gargoyle, it must have been noticed by many that the two actresses contrasted both in looks and in temperament. The blue-eyed blonde Laye was tall, cool and sophisticated, but maybe slightly aloof, whereas Matthews, although not classically beautiful, had a sexual attractiveness and zest for life that many found utterly beguiling. One of them, unfortunately, was Evelyn’s husband Sonnie Hale. There was a reason the Sunday Times theatre critic James Agate had once described Matthews as ‘the rogue in porcelain’.

Matthews was also married, but in her case to a womanising, debt-ridden actor called Henry Lytton Jnr. He had a famous name, but only because of his father, who was the popular Gilbert and Sullivan comedian Sir Henry Lytton Snr. Although the couple were now all but estranged, Matthews had married Lytton to seek stability in a life that must have become extraordinarily unreal when she quickly shot to stardom. The young actress from the wrong part of Soho thought the famous theatrical family could offer her a form of stability in her life, but the security she sought crumbled after just a few months.

Lytton, an insecure man, had not only been sleeping with chorus girls behind Matthews’ back (he’d actually been having an affair with one young woman from the very week they had been married), but he had become increasingly envious of her growing success. In fact he was envious of anybody’s success and for the rest of his life found it impossible to emerge from the shadow of his eminent father. Lytton Snr didn’t help by disinheriting his son from his will (he died in 1936), as he disapproved of not only his son’s theatrical career (what there was of it) but also his marriage. Lytton Jnr ended his show business days as a ringmaster at Blackpool Tower Circus alongside Charlie Cairoli. He died in the same town aged just fifty-nine.

In 1928, early in the new year, Evelyn Laye travelled to Manchester where This Year of Grace was previewing. When she arrived at the theatre she caught her husband and Matthews holding hands. On seeing her, the co-stars quickly and expeditiously moved away from each other and Laye, pretending to joke, asked whether they were in love with each other. They nervously laughed and assured her that the idea was absurd and foolish. It was, as Sonnie pointed out, less than a month to only their second anniversary. Jessie and Sonnie were lying. They had already been lovers for several weeks. At a rehearsal, after they had sung ‘A Room with a View’ together, Sonnie had whispered in her ear, ‘Let’s make it come true.’ The next day he took Matthews to the romantic French restaurant called Moulin d’Or on Church Street in Marylebone.

This Year of Grace opened to rave reviews both for Jessie and, to his great relief, the writer Noël Coward (it resurrected his career). The Sunday Express ranked Jessie Matthews and Evelyn Laye, together with Cicely Courtneidge, as ‘the three brightest female stars of our English light musical stage’. This would have rankled with Laye, who saw herself as London’s reigning stage beauty, and this only got worse when the song ‘A Room with a View’ became a huge hit that summer. A few weeks later, Evelyn Laye found passionate and rather explicitly detailed love letters, written in an ill-educated childish scrawl, from Jessie to Sonnie. After confronting her husband with them, he admitted his love for Matthews.

Sonnie Hale marrying Evelyn Laye

Laye at the time was performing at the Daly’s Theatre (in Cranbourn Street just off Leicester Square and demolished in 1937) in a show called Lilac Time, an English version of Das Dreimäderlhaus (House of the Three Girls), a Viennese pastiche operetta with music by Franz Schubert. A depressed Laye had started to shrink away from her friends and even her colleagues in Lilac Time: ‘I was either tortured by jealousy or helpless self-pity,’ she once wrote. ‘I never knew when I might be crying. I could be walking along a street and suddenly find them streaming down my face.’

Early in 1929, Noël Coward came to see Laye who was still very low about Sonnie and Jessie, and offered her a new play that he had written and C. B. Cochran would be producing. ‘I’m calling it Bitter Sweet,’ he explained eagerly, ‘and Cocky wants you to play the lead.’ Laye knew that the writer and producer had worked together on This Year of Grace and spun around on her dressing room chair and howled, ‘You can tell him I’d rather scrub floors than work for him again. Sonnie met Jessie in one of his shows, they were together in one last year and they’re together in the new one now. Cocky knows about them, so go on, tell him!’ More than unused to people saying ‘no’, a rather shocked Coward gave Laye a perplexed, exasperated look and then walked out of the room, taking his manuscript with him.

Bitter Sweet opened later that summer with an American actress and singer, Peggy Wood, in the leading role (thirty-five years later in 1965 she played the Abbess in The Sound of Music, singing ‘Climb Every Mountain’). Another actor in the production was twenty-seven-year-old Alan William Napier- Clavering, better known as Alan Napier, who, after a decade in West End theatres and a long film career, became best known to most people for portraying Alfred Pennyworth, the butler in the 1960s Batman television series. After the opening in Manchester (a Cochran tradition), the Manchester Guardian wrote that there was nothing to stop the show doing well: ‘If a wealth of light melody, a spice of wit, and much beauty of setting can assure it, Mr Coward need have no misgivings’.

However when Laye heard Cochran was sending another company to perform Bitter Sweet in New York, she swallowed her pride and asked for an audition with Coward. It was agreed and she insisted she sang the whole score with the playwright initially watching from the stalls at the Scala theatre on Charlotte Street. During most of her performance, however he disconcertantly paced up and down the aisle, and when she finished he came round to the stage and said, ‘It’s good, darling.’ He then kissed her and said in a matter-of-fact voice, ‘Now I’m going to get some lunch,’ and disappeared. Elsie April, Cochran’s musical director, was also present and said, ‘There’d have been no lunch for him, or for you, if he hadn’t liked it.’ Indeed Laye was soon informed the part was hers. There was a reason, however, why Laye decided to audition for a part that she initially had turned down: she needed the money. During an interval a few days before, she had got a call from her stockbroker: ‘Boo, I’ve got to tell you, I’ve lost all of it. I put the lot on what I thought was a good speculation. It’s crashed.’ He had just lost her £10,000 (approximately £600,000 in 2017).

Kenneth Alexander, Evelyn Laye in One Heavenly Night directed by George Fitzmaurice, 1931

When Bitter Sweet opened on Broadway, after effusive preview reviews, it was so popular the police had to cordon off Sixth Avenue. Coward told his mother that the production was ‘the most triumphant success I’ve ever seen. When she made her entrance in the last act in the white dress they clapped and cheered for two solid minutes and when I came on at the end they went raving mad.’ After telling her that Laye was ‘weeing down her leg with excitement’, Coward complimented his mother: ‘How right you were with Evelyn – she certainly does knock spots off the wretched Peggy!’

However while Evelyn Laye was receiving acclaim in New York, in the UK the Daily Mail’s headline on 22 November 1929 was: ‘Miss Jessie Matthews’ divorce suit. Discretion in her favour. Sonnie Hale named.’ The following summer in the Probate, Divorce and Admiralty Division of the High Court of Justice on the Strand, Evelyn Laye’s divorce petition came before Sir Maurice Hill – a judge who was close to retirement and particularly averse, in an almost prehistoric fashion, to divorce. Evelyn Laye, with her deposition taken earlier, was away filming One Heavenly Night in Hollywood. Against all advice Matthews was present in the courtroom, but soon realised her mistake when her private letters to Sonnie were read out in open court:

My Darling, I want you and need you badly, all of you, and for a very long time. I am lying here, waiting for you to possess me.

The dear little boobs, which you love so much, are waiting for you also.

During the reading of one particularly embarrassing letter Matthews fainted and had to be helped outside. Whether it was an act or not, it garnered no sympathy from Sir Maurice Hill, who once described his legal work as ‘having one foot in the sea and one foot in the sewer’. Perhaps the judge’s mood can be blamed on his being an England cricket fan – it was that very day at Headingley in Leeds that Don Bradman scored a 100 before lunch, 219 by tea and ended the day with 309 not out – but whatever the reason, his final comments, written down with glee by the watching reporters, were spoken with brutal severity:

It is quite clear that the husband admits himself to be a cad, and nobody will quarrel with that, and the woman Matthews writes letters which show her to be a person of an odious mind.

19th December 1930: British actress Jessie Matthews (1907-1981) wearing one of her exotic costumes for Cochran’s new musical ‘Evergreen’, at the Adelphi Theatre, London. (Photo by Sasha)

Later that year, Jessie and Sonnie appeared in another Cochran musical, Ever Green, again with music written by Rodgers and Hart. It premiered on 3 December 1930 and was the first show at the newly renovated Adelphi Theatre. It was an expensive production – Cochran had agreed to pay Matthews a remarkable £250 a week and just before the curtain went up on the first night told her, ‘I’ve spent tens of thousands of pounds on this show. So now it’s all up to you!’ The production was notable for using London’s first revolving stage during the song ‘Dancing on the Ceiling’ when the two stars danced around a huge chandelier that was standing up from the floor, simulating the ceiling. The song, rejected from a Broadway musical earlier that year, became one of Jessie Matthews’ signature tunes, although it was banned for a while by BBC radio because the word ‘bed’ was used twice in the verse and once in the refrain. The staging of it was not without struggle, and Matthews, still upset with her ongoing marital difficulties, later wrote:

Dancing on the Ceiling was the big song and dance number in the show, and the way those men mauled it about! ‘She’s too coy’ said Benn Levy (who wrote the book); ‘she isn’t coy enough’ said Rodgers. ‘Sweeter and lighter’ said Hart. ‘I don’t like it’ said Cochran. I looked down at these four men so busy manipulating me. I felt like a puppet with tangled strings. Some demon took hold of me. What was I to them? Nothing but some image they had in their minds, an object, a bloody blueprint to scrawl their ideas on. I was sick and tired of letting four old men mess me about. What the hell did they know about love? How did they know how a girl in love really feels?

Despite the public criticism over Evelyn Laye’s divorce, for which Matthews was almost entirely blamed, Ever Green easily became her biggest stage success and was the greatest of all the Cochran musicals.

Jessie and Sonnie Wedding Day Sat. 24 January 1931 with Cochran Hampstead

In January 1931, Sonnie Hale and Jessie Matthews married at Hampstead Register Office, and he was to have a major influence on her career during much of the decade. Their marriage wasn’t always a happy one and almost immediately there were problems. The Hales, a big theatrical family, never accepted Jessie like they had Evelyn. Robert Hale, a Scottish comedian, had told her in 1928 after meeting her for the first time, ‘Don’t let on to the old lady that we’ve met, will you?’ The ‘old lady’ was Belle Reynolds, an Irish actress who had failed to hide her dislike of Jessie right from the start – likewise Sonnie’s sister Binnie, who was also a big star at the time after appearing in No No Nanette in 1925 at the Palace Theatre. Binnie, responsible for making the song ‘Spread a Little Happiness’ popular, would perform Evelyn Laye impressions on the piano if Jessie ever came to visit. Behind her back, however, Binnie’s impressions of Jessie were of a ‘cockney guttersnipe affecting ladylike airs and graces’.

Two months after the wedding ceremony, Jessie’s first major film, Out of the Blue, was released. The Daily Mirror called it a ‘charming and amusing trifle’ and said Jessie Matthews ‘was good in the leading role’ but the newspaper was being kind. The film was atrocious and she looked frightened out her wits in front of the camera. Despite Sonnie Hale’s conviction that ‘the future was in the film industry’, he and Jessie were bitterly disappointed with the movie. Michael Balcon, then in charge at Gainsborough and later to run the famous Ealing Studios, initially felt that Jessie ‘was a dead loss as far as films are concerned’, but after seeing some early rushes of her next film he signed her to a two-year contract.

Jessie and Sonnie from There Goes the Bride

In the autumn of 1932, There Goes the Bride, directed by Albert de Courville was released (although Balcon was working her so hard, Matthews had completed the films The Man from Toronto, The Midshipman and the excellent The Good Companions before its premiere), and Jessie received a delighted reception. The Observer wrote:

What really matters is the discovery of Jessie Matthews. Miss Matthews is a revue actress, who doesn’t know much yet about film angles, tricks, and paces but she is going to be the biggest star name we have in their country before she is through. Her pert little face photographs irresistibly.

The Daily Mail was similarly unrestrained in its praise: ‘Miss Matthews is personality and a portent. Her arrival is a revolution. I feel certain she will be a sensation.’ The ramifications over the divorce scandal, however, were still affecting Jessie’s life and she was not allowed to meet King George V and Queen Mary with the rest of the cast at The Good Companions premiere.

These films were followed by a series of stylish and escapist musicals, the most popular of which was the filmed version of her stage success Evergreen, directed by Victor Saville in 1934. Just as the shooting of Evergreen was coming to an end, Evelyn Laye returned from Hollywood. One Heavenly Night had been unsuccessful in America and she had come back to star in Princess Charming for Gaumont- British in Shepherd’s Bush. One day she came to the same studio as Jessie. Lionel Burleigh, a costume designer, often recounted a story of how he once took a lift at the studio with Evelyn Laye on one side and Jessie on the other, both looking resolutely ahead and not saying a word. When the lift reached the dressing room floor, neither wanted to leave it first. Finally they all moved forward simultaneously like ‘an automaton chorus line from The Chocolate Soldier’.

Jessie Matthews Evergreen 1934

On 7 June, Evergreen opened at the beautiful New Gallery cinema at 121 Regent Street (later, and for forty years, a Seventh-Day Adventist church, then Habitat and now Burberry’s flagship store) and completely captivated the critics, including C. A. Lejeune in the Observer: ‘Jessie Matthews grows so much in stature in every part she tackles that our directors might safely dispense with their production numbers and leave it to her to pull them through. Her movement and poise in this new picture of Victor Saville’s is enchanting.’ The Daily Mirror concurred, saying, ‘Jessie Matthews gives the finest performance of her screen career in Evergreen,’ but continued, ‘Her performance is more remarkable as during the whole six weeks the picture was being made, Miss Matthews was ill, and had to stop work repeatedly to recover her strength.’ This was the first time it came to public knowledge that all was not well in Jessie Matthews’ life. During the production of Evergreen, Jessie had continually collapsed and had been close to a complete nervous breakdown.

Meanwhile in the States the movie also got great reviews. In New York the film opened at the Radio City Music Hall, and Variety almost yelled from the very high rooftops their appreciation of the girl from Soho:

The most sensational discovery in years. Princess Personality herself. She can sing. She can dance. She can act. She can look. She has charm, youth, beauty and a million dollars of magnetism. This is not a prediction, this is a promise. Jessie Matthews will be one of the biggest box-office bets in America within the next six months.

But that was it. What seemed a certain Hollywood career never happened. As Victor Saville, who directed most of her best films, admitted: ‘The big problem was to find a dancer capable of partnering Jessie. We never did.’ Saville thought that Fred Astaire would have been the perfect partner. The thirty-five-year-old American performer was in London at the time, dancing with Claire Luce at the Palace Theatre in The Gay Divorce (his first stage musical without his sister Adele, who had married Lord Charles Cavendish the previous year). RKO, however, had him under contract and refused to release him. Jessie carried the next few films almost by herself, and indeed often danced alone.

The two-year contract she had signed with Michael Balcon in 1932 was now coming to an end, and she horrified him by saying that she wanted a year’s break from the business. A month after the Evergreen premiere, she went to Ilford to open a fete in aid of the People’s Dispensary for Sick Animals, but at the entrance she suddenly collapsed and fell to the ground unconscious. Two weeks later the bad news turned to good news when it was reported that Miss Jessie Matthews was to have a baby. Sonnie was quoted in the newspapers: ‘We have always wanted a baby. Jessie is very fit and happy.’

On 7 December 1934, Evelyn Laye married again, this time to the Young Woodley actor Frank Lawton, who had been at the late supper at the Gargoyle Club where Laye and Matthews had first met. The couple were to remain happily married until Lawton’s death in 1969, and Evelyn continued to work in the theatre until well into her nineties. Just eleven days after Laye’s marriage, on 18 December and after a fall in her garden, Jessie and Sonnie’s son was delivered two months early. He was named after his father and his grandfather, but after just four hours John Robert Hale-Monro the third died.

First A Girl Jessie Matthews

Despite this awful setback, and with her mental health still in the balance, Jessie was at the peak of her popularity, and in 1935 her film First a Girl was released. Based on Reinhold Schunzel’s Viktor und Viktoria, Jessie played a young woman acting as a male musical artist famous for his female impersonations. Men dressing as women, and women as men, has long had a part in British theatrical history but the Observer critic C. A. Lejeune was not impressed:

I have a violent physical animus against men dressed up as women and women dressed up as men. It distresses me to see Jessie Matthews and Sonnie Hale, both of whom I admire enormously, reduced to this sort of undergraduate antic.

Jessie and Robert Hale It’s Love Again

Another film, It’s Love Again, came out the following year and again received more enthusiastic reviews, including one from Graham Greene: ‘For once it is possible to praise an English “musical” above an American. Victor Saville has directed It’s Love Again with speed, efficiency and a real sense of the absurd.’ Not long after the film’s release and following a salary dispute, Victor Saville, who had directed all Jessie’s best films, left Gaumont- British. On Jessie’s insistence her husband Sonnie took over the directing role in her films, despite his inexperience. The critical reception for the three Jessie Matthews vehicles directed by Sonnie were noticeably less fulsome. Graham Greene wrote of Gangway in 1937:

Miss Jessie Matthews has only been properly directed by Mr. Victor Saville. Mr Sonnie Hale, whatever his qualities as a comedian, is a pitiably amateurish director and as a writer hardly distinguished.’

Early in 1939, with the Gaumont-British contract coming to an end, Jessie and Sonnie decided to put on a lavish stage musical starring themselves. The provincial tour of I Can Take It was particularly successful, and everyone was looking forward to the show opening in London at the Coliseum. The planned opening night on 11 September 1939 turned out to be a week after war with Germany was announced. It was awful timing. All the theatres in the capital were ordered to be closed by the Government and the production was cancelled. The couple had invested in the production and lost heavily.

In the summer of 1941, Matthews was given a contract for a Broadway musical called The Lady Comes Across. In August, she flew via Lisbon on a Pan American Boeing 314 ‘Clipper’ flying boat over to America. The B-314, in overnight sleeper configuration, accommodated forty passengers in seven luxurious compartments, including a fourteen-seat dining room and a private ‘honeymoon suite’ at the tail end of the plane. Accompanying her on the fifteen-hour flight was the actress Bebe Daniels but also Rose Kennedy, the wife of the US Ambassador and mother of the future president. Jessie took with her a collection of bomb splinters and air-raid souvenirs, which she planned to auction for British war charities over in America.

The rehearsals of The Lady Comes Across were first delayed, and then fraught with difficulties. Whole sections of the musical were totally rewritten, and the show, again with awful timing, opened for previews in Boston in the very week the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbour in December 1941. In an interview with Elliot Norton of the Boston Post, an uptight Matthews said: ‘If you walk by a candy store you don’t even notice. If I do, I am almost nauseated by the smell. It is so long since we have had enough candy, or even sugar, in England. Recently I had to ride for miles on a bicycle even to get an egg.’ A month later Jessie collapsed and was taken to the Columbia Presbyterian Medical Centre in New York. Sonnie Hale was appearing in pantomime in Newcastle and told the press:

I would like to be able to go straight out there, but it would throw too many people out of work, so I am carrying on, but it won’t be so easy to play a comic part when one is so worried.

Before the illness it was well on the cards that I could sell her to Louis B. Mayer. But after the breakdown it was hopeless. Nobody wanted to know.

When Jessie returned to Britain, she found out that Hale had fallen in love with the nanny who had been employed to look after their adopted daughter, Catherine. A year later they were divorced. Jessie Matthews never returned to the popularity of her pre-war years. Her style of dancing and singing appeared old-fashioned, which wasn’t helped by the cut-glass accent from her teenage elocution lessons. At the age of fifty-six she emerged from more than a decade in the show business wilderness when she took on the role of radio’s Mrs Dale, the paragon of middle-class respectability. In 1970 she was awarded an OBE, but by now she had become slightly more rotund and matronly than in her lithe days as an actress and dancer during the twenties and thirties. It is a fate that comes to most, but after watching Jessie at a charity gala, Evelyn Laye, who had never quite forgiven her, and who retained her slim, gracile figure throughout her life, was as waspish as her waist and said: ‘Oh look, the dear little boobs have become apple dumplings.’

Jessie Matthews 1933 postcard

Jessie Matthews in First A Girl

Sailing Along Jessie Matthews Michael Redgrave 1938

Its Love Again (1936) with Robert Young and Sonny Hale.

In 1995, fourteen years after Jessie died of cancer aged seventy-four, a plaque was erected to her on the wall of the Blue Post pub on Berwick Street – the road where she was born. The stallholders suspended their familiar cries and the street went quiet when Andrew Lloyd Webber unveiled the blue plaque.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.