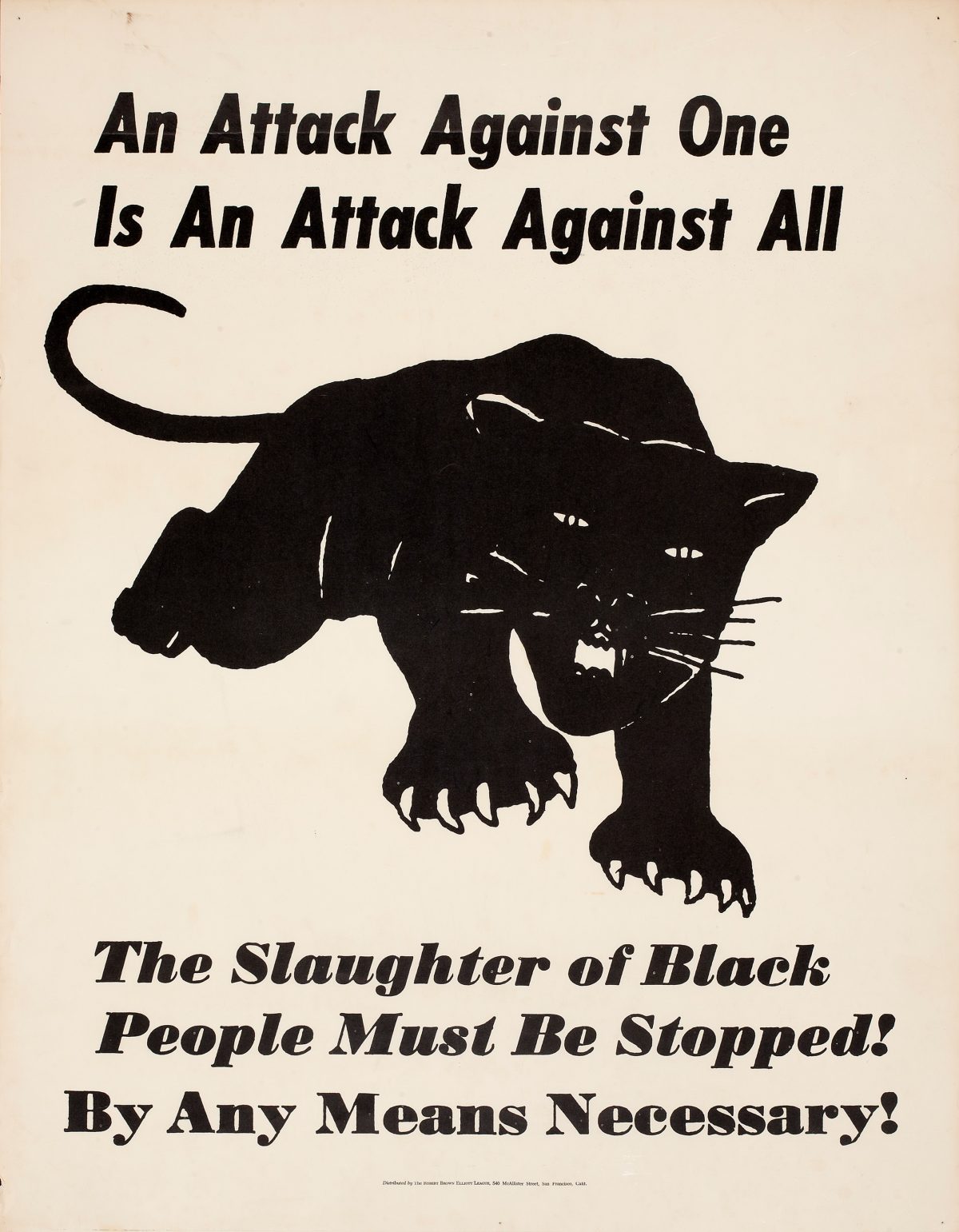

“The panther was an animal that if put into a corner it would attack. But it wouldn’t attack anyone unless it had to defend itself.”

-Emory Douglas

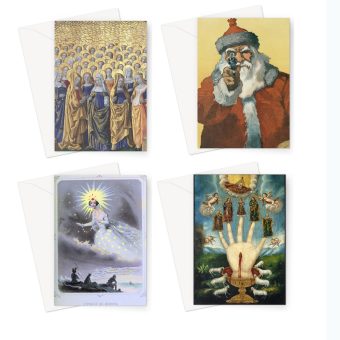

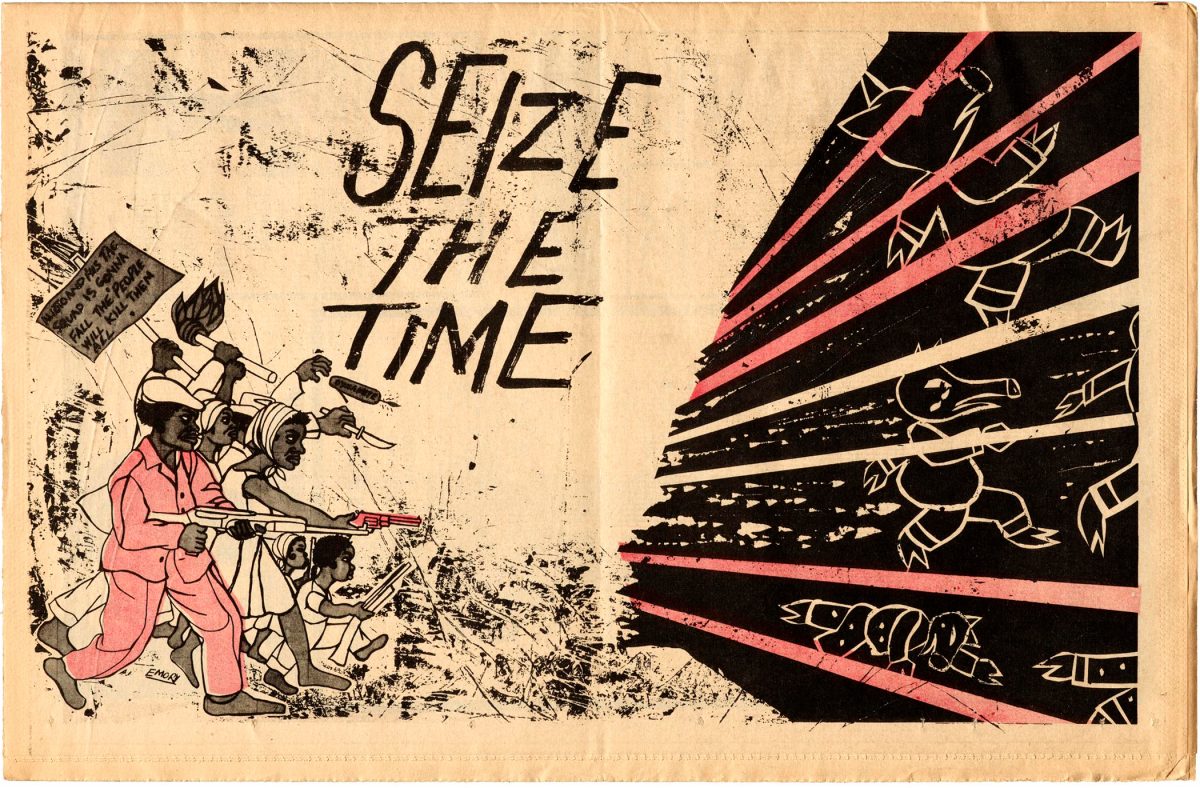

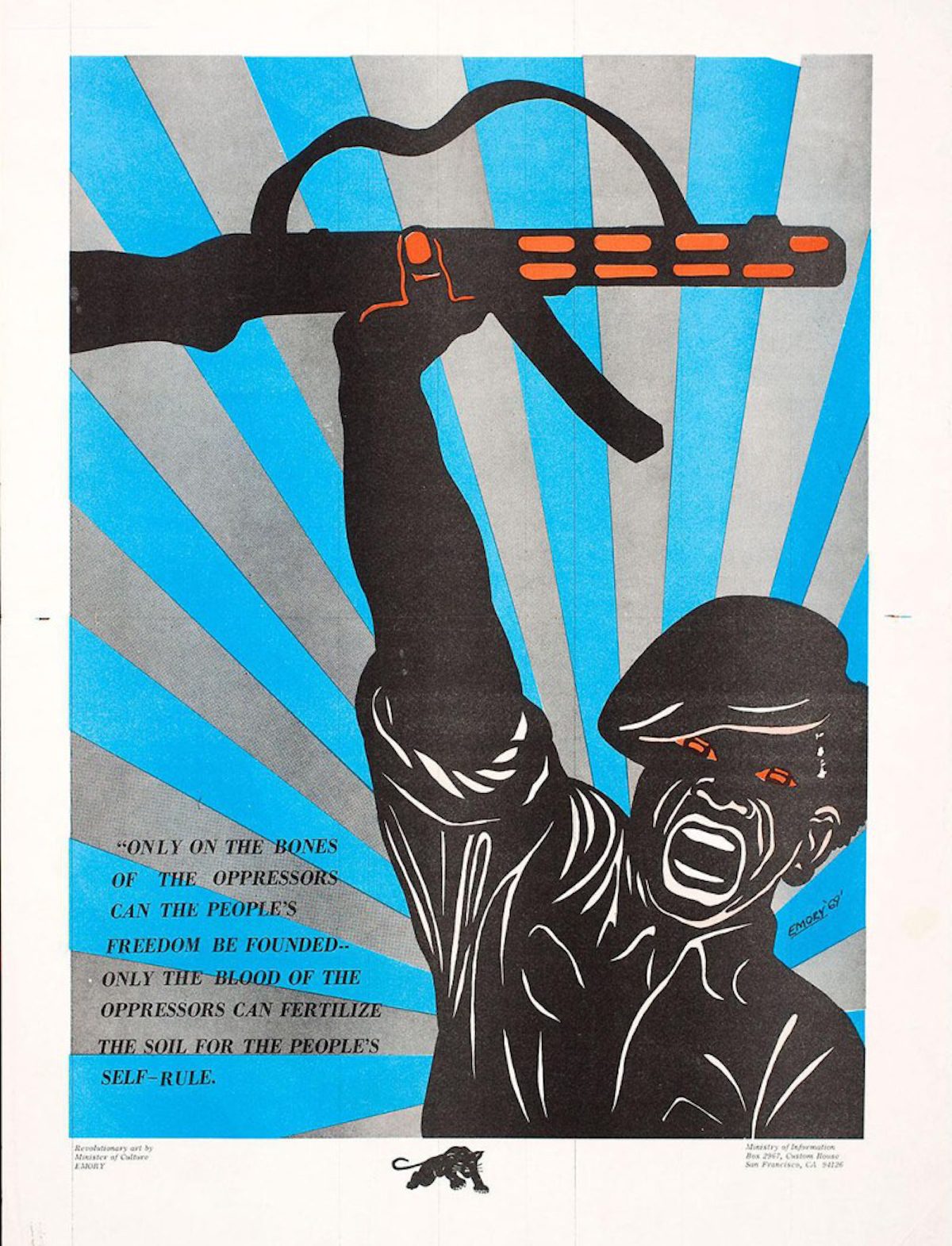

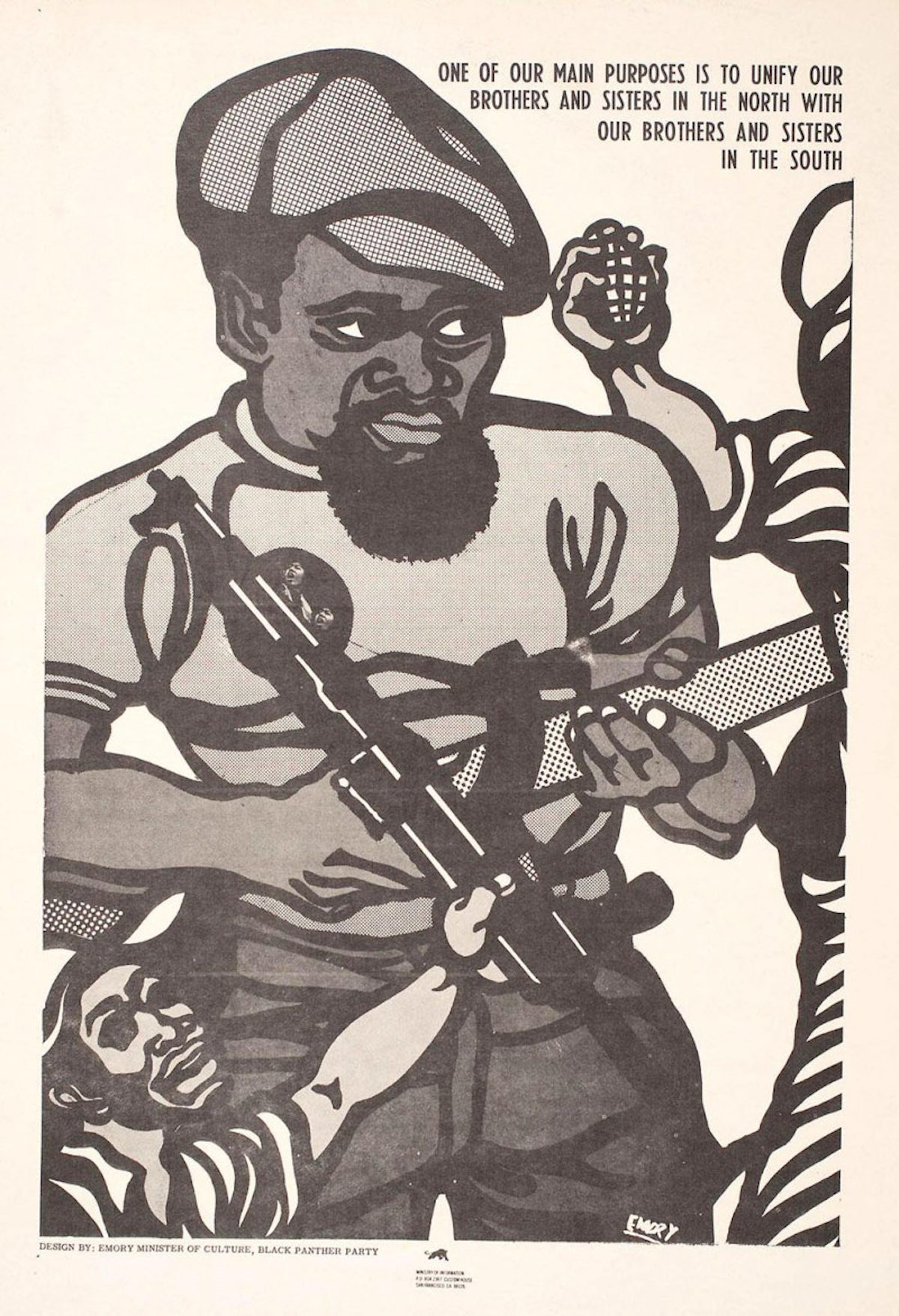

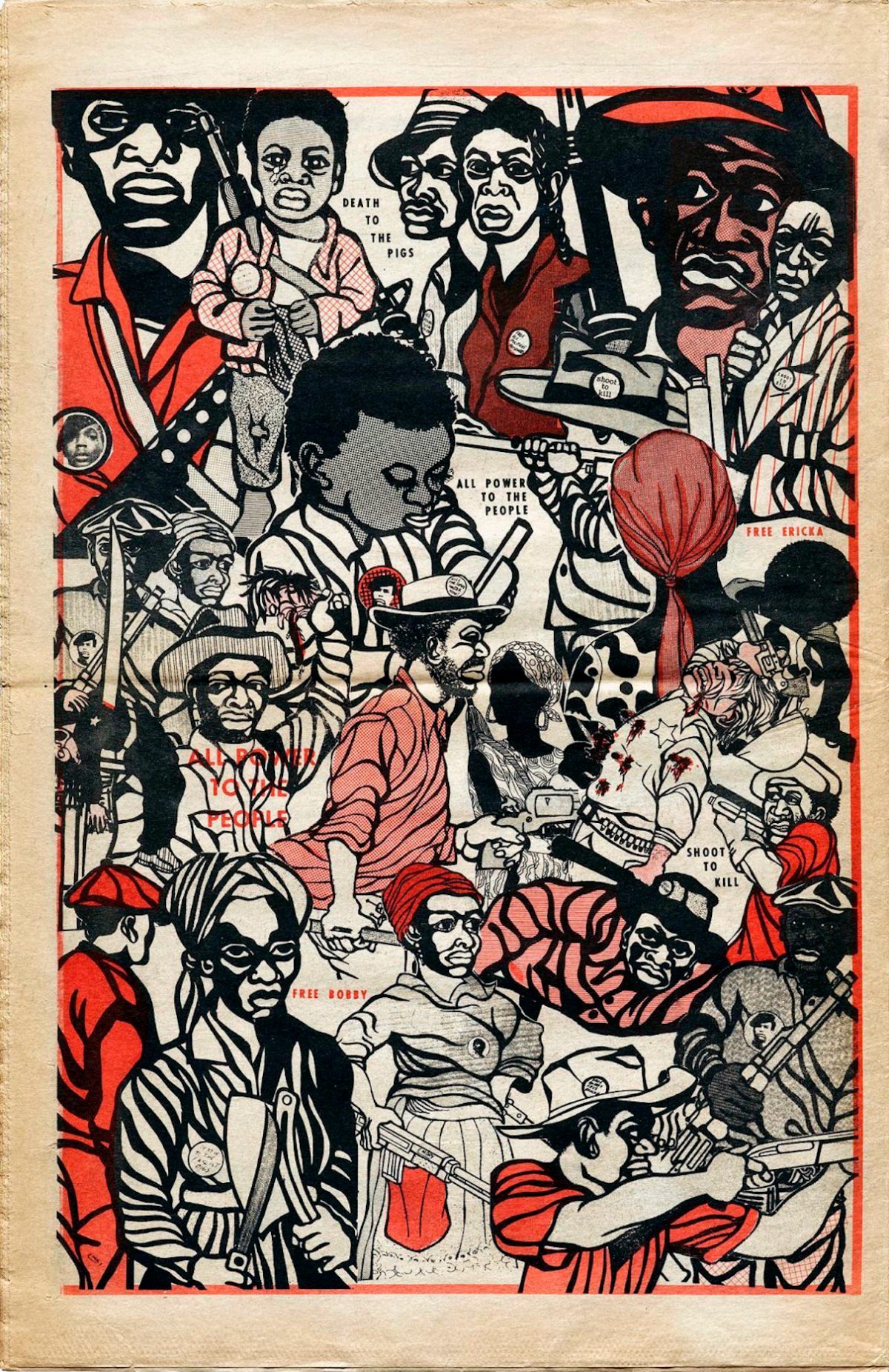

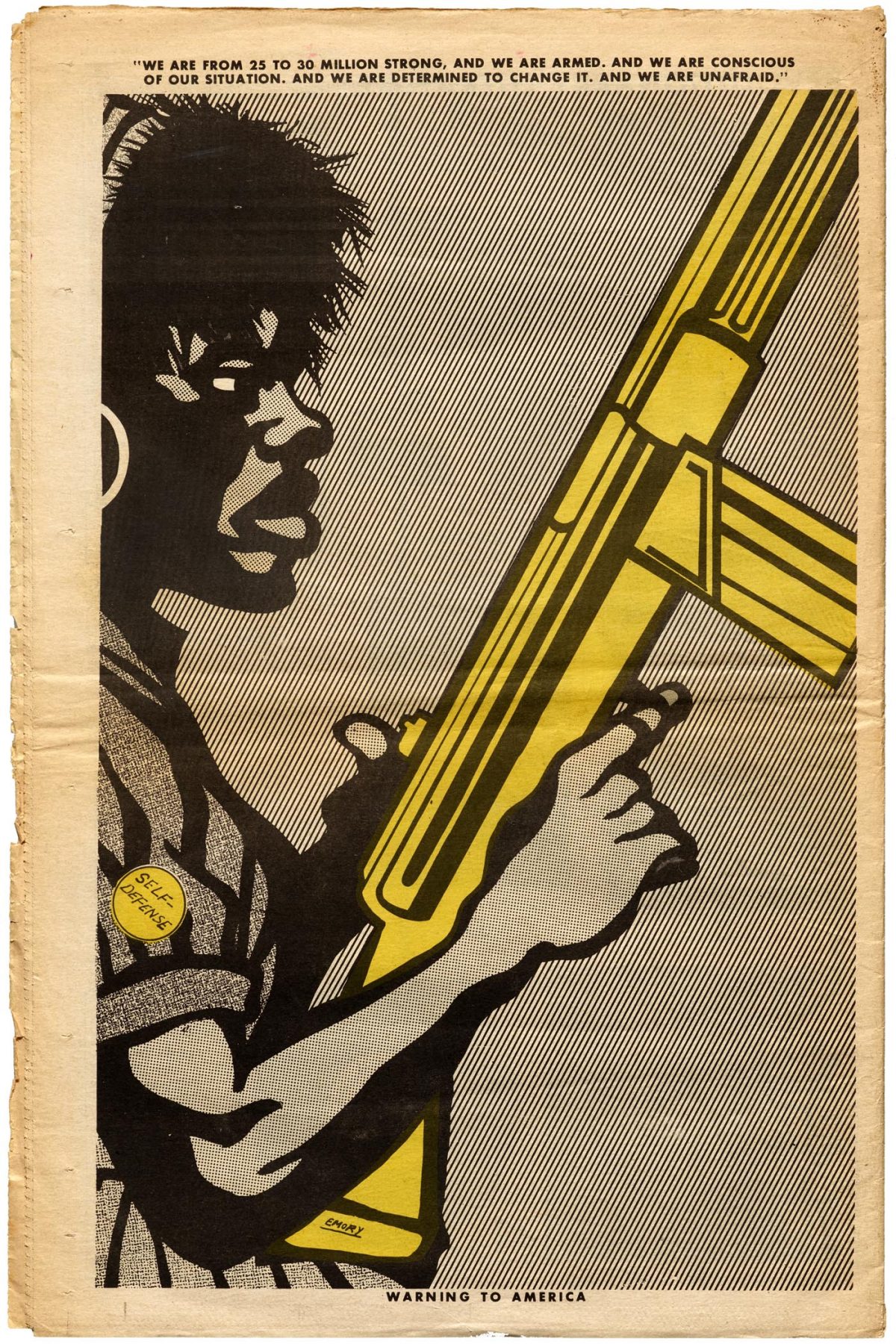

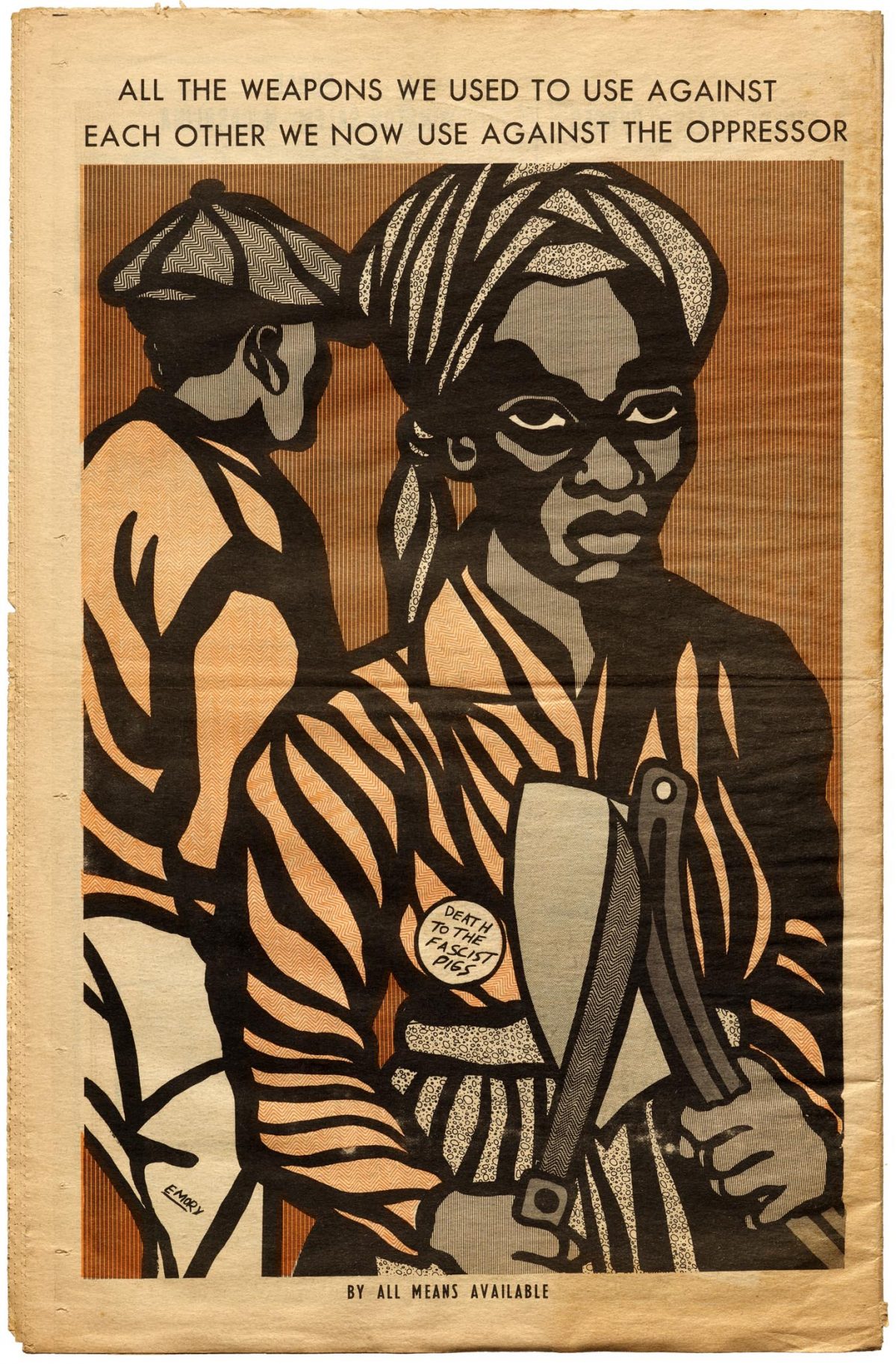

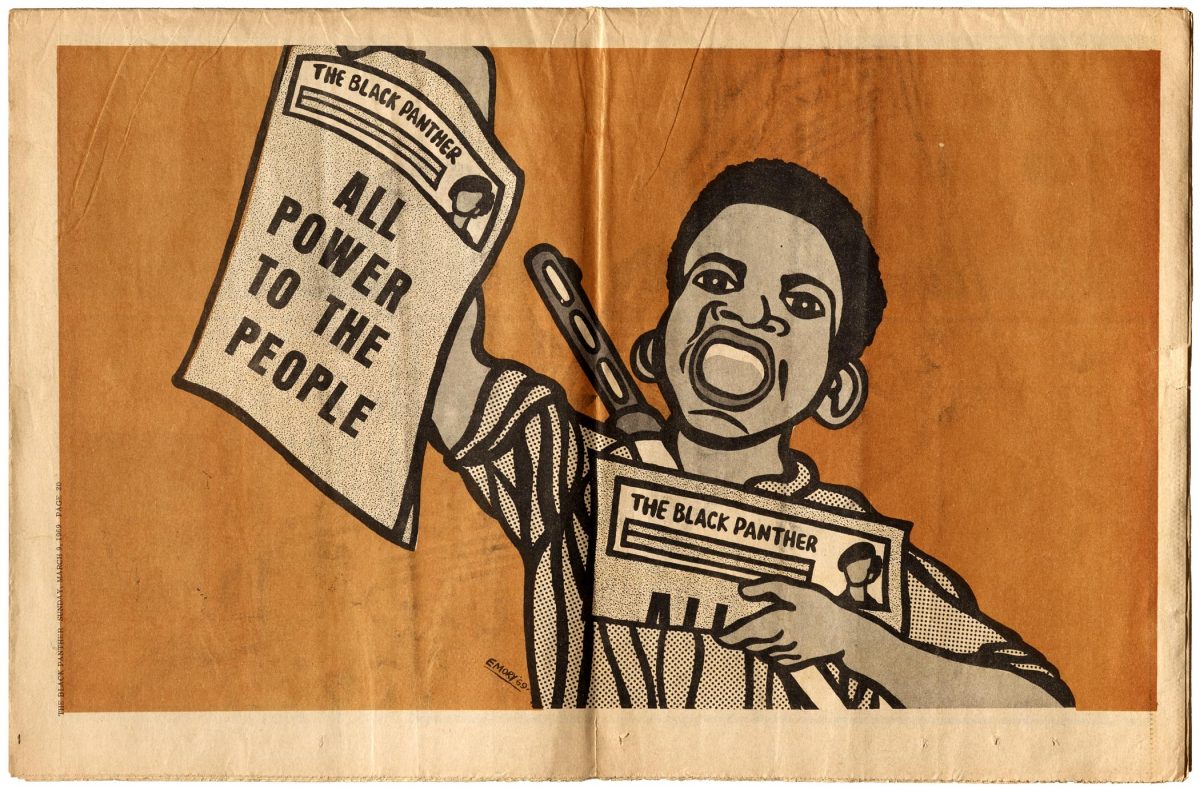

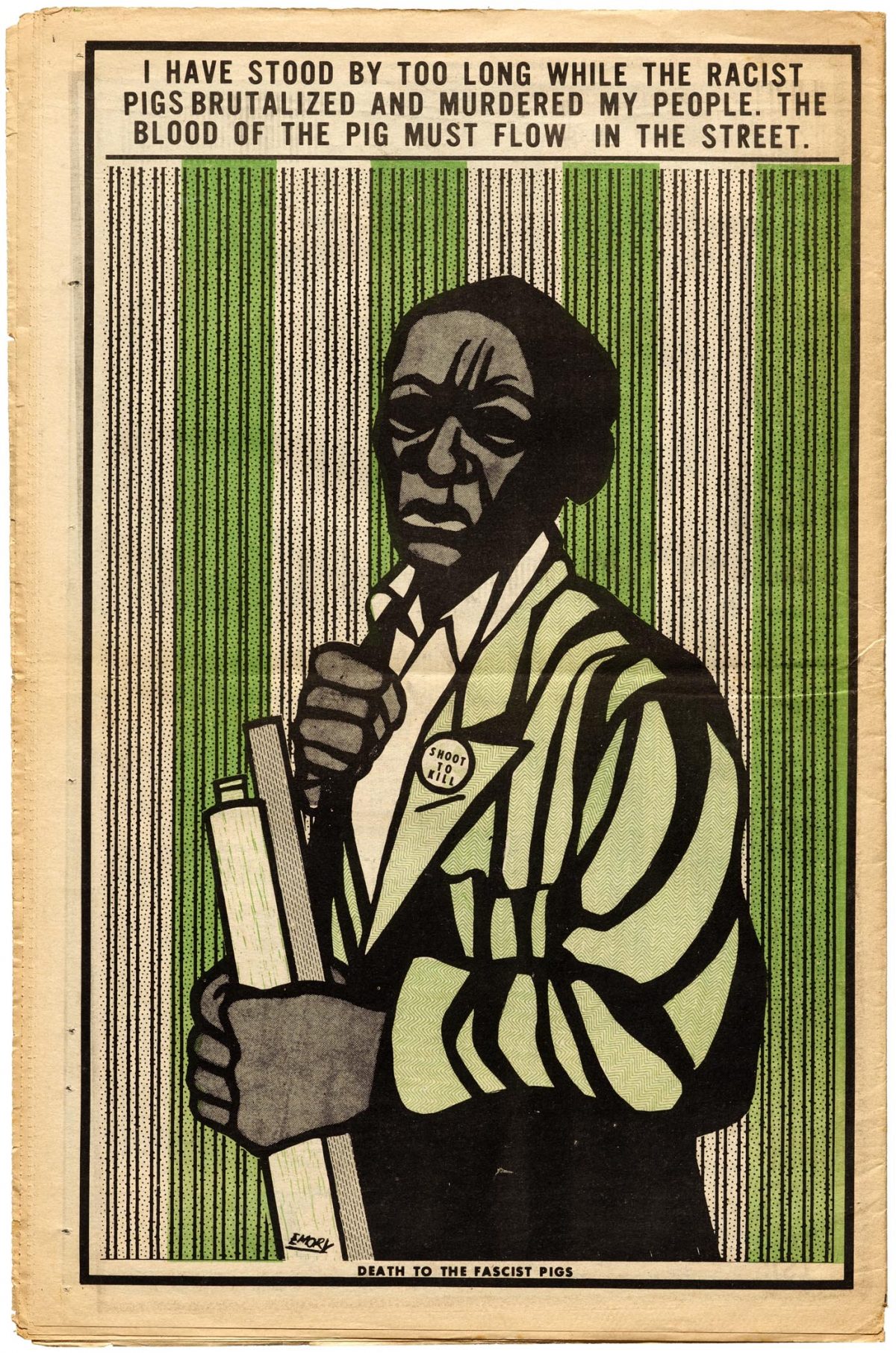

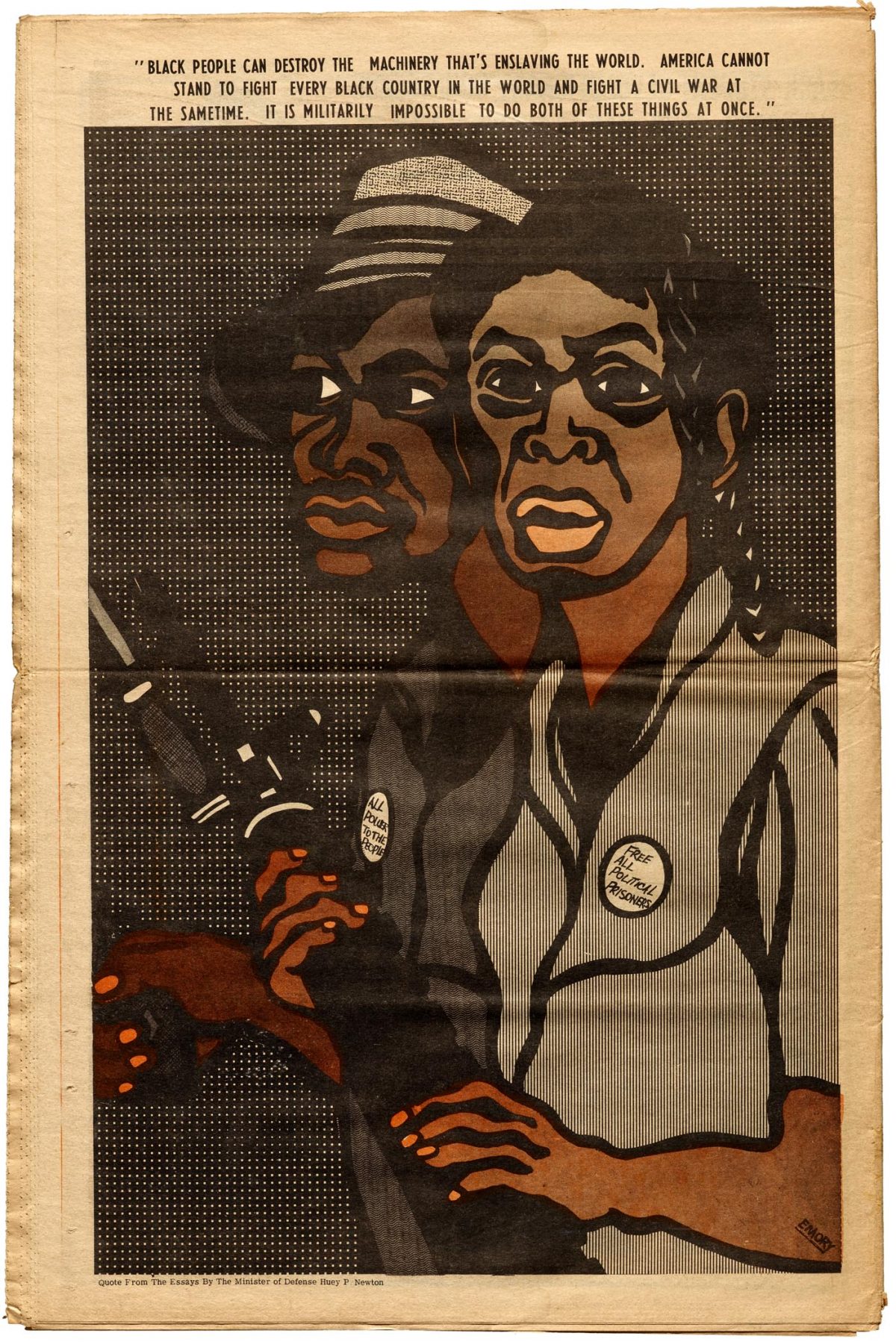

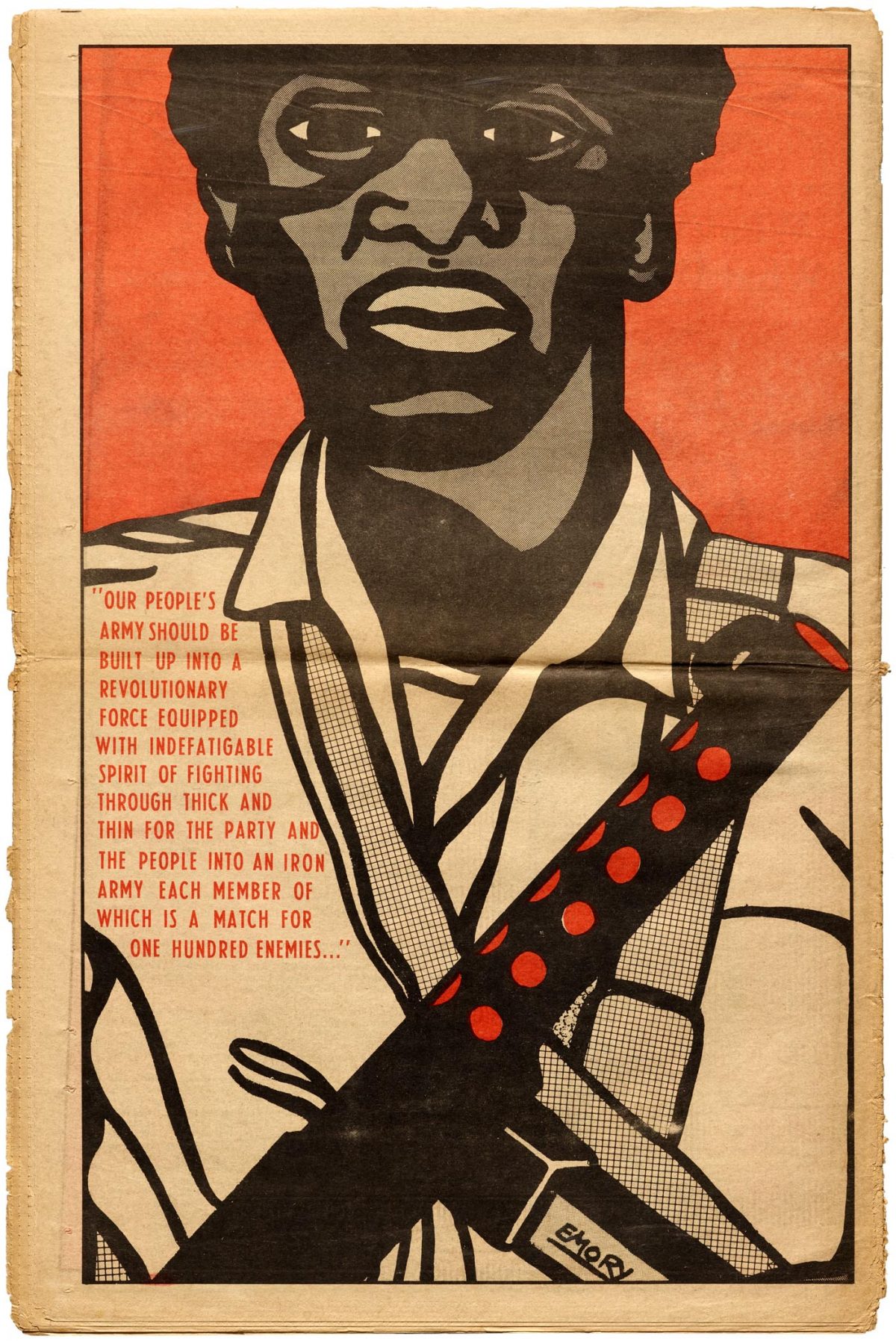

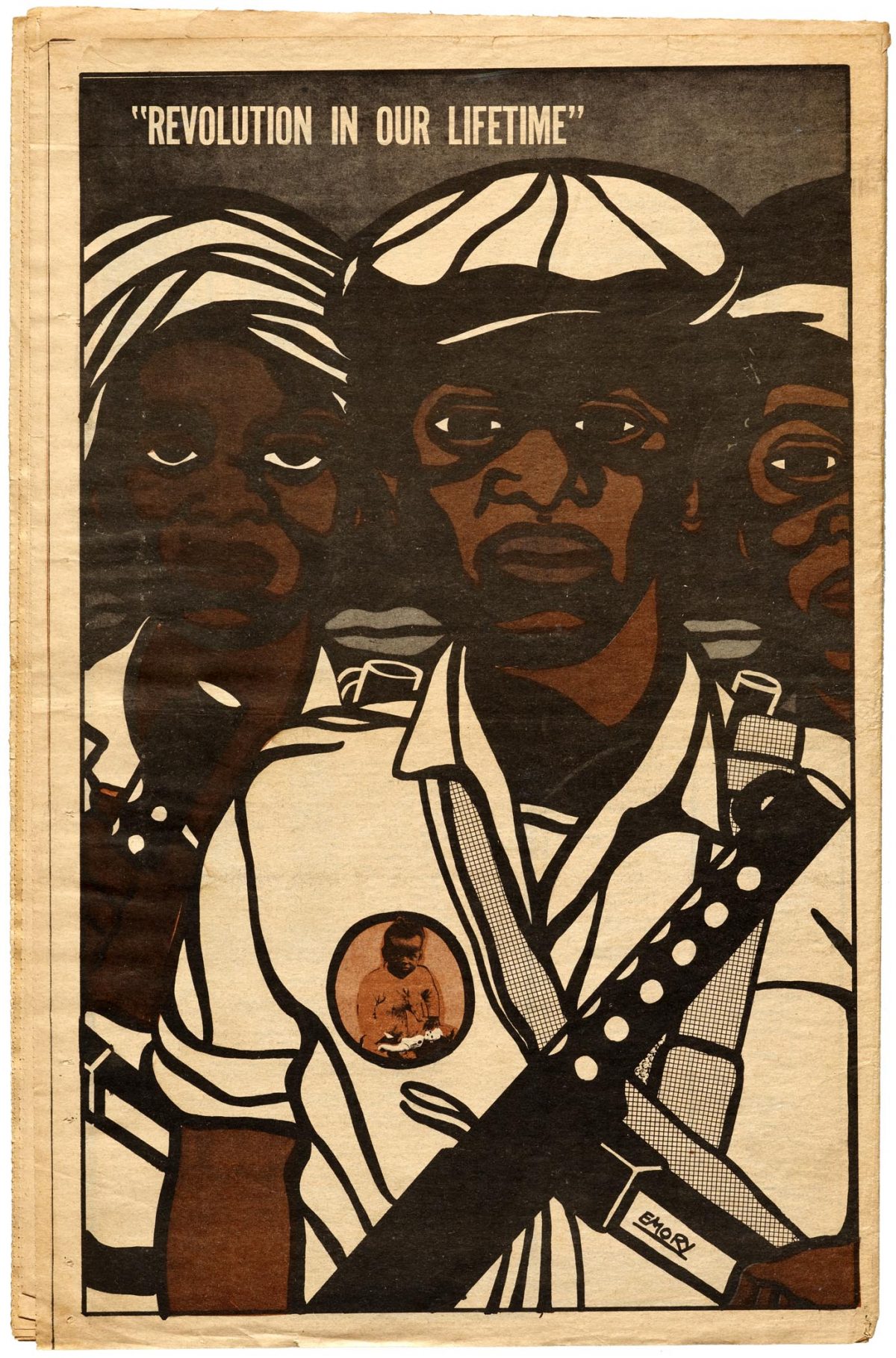

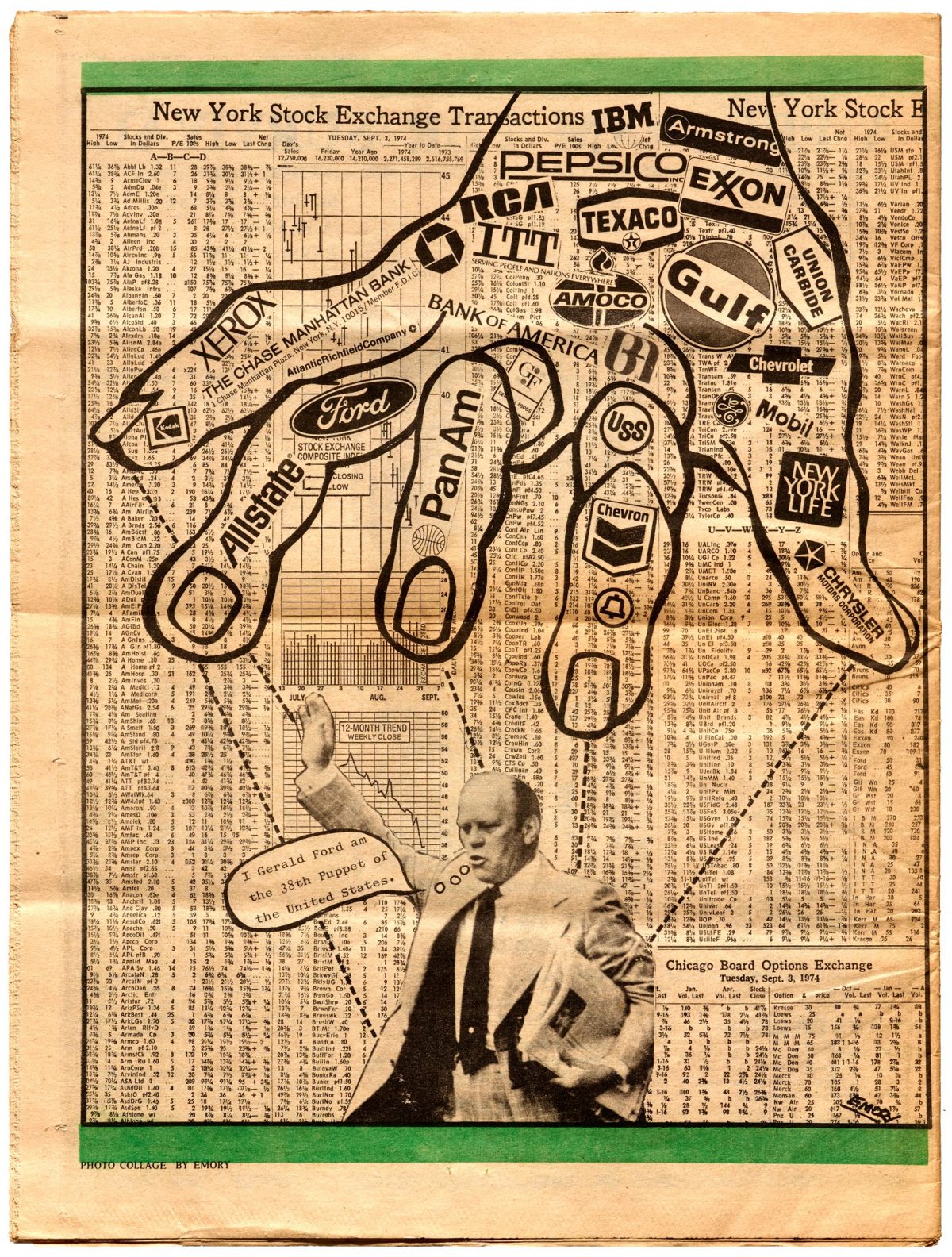

Every revolutionary movement has its graphic art—bold lines, eye-catching colors, slogans aplenty. It is a form so well-worn as to have become cliché, a mode of communication that evolved with advertising and newspapers and used the same technologies. So it was with the Black Panther Party for Self Defense, whose radical posters and revolutionary newspaper, The Black Panther, carried the party’s message around the world, thanks to artist Emory Douglas, inventor of the Black Panther aesthetic.

The rifles, leather jackets, and berets may have originated with party founders Huey Newton and Bobby Seale, but the look of the party on paper was all Douglas, who met Newton and Seale in 1967, the year of the party’s founding, and signed on right away. As he describes it, conditions in Northern California were no different for black Americans than they had been in the deepest South.

In the ’50s and ’60s there was segregation here in the Bay Area and all over the country. There was a curfew for young blacks my age in the Fillmore district where I lived. It was a disturbing thing. There were civil rights movements here in San Francisco. They would show on the national news the dogs being sicced on the marchers, being sprayed with the hoses, being beaten with the batons.

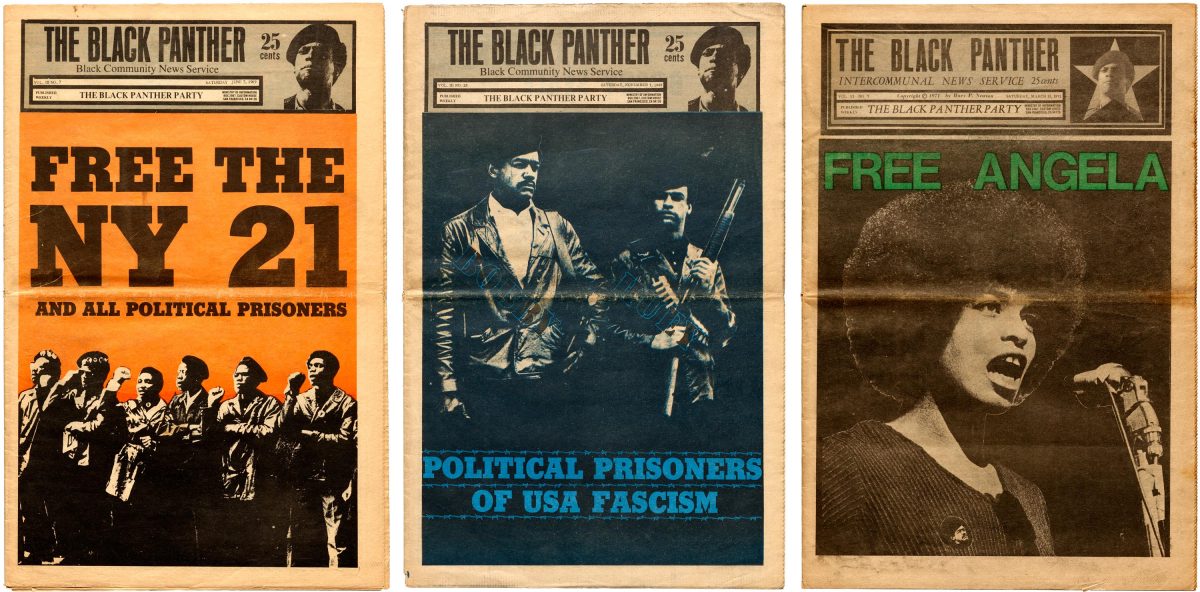

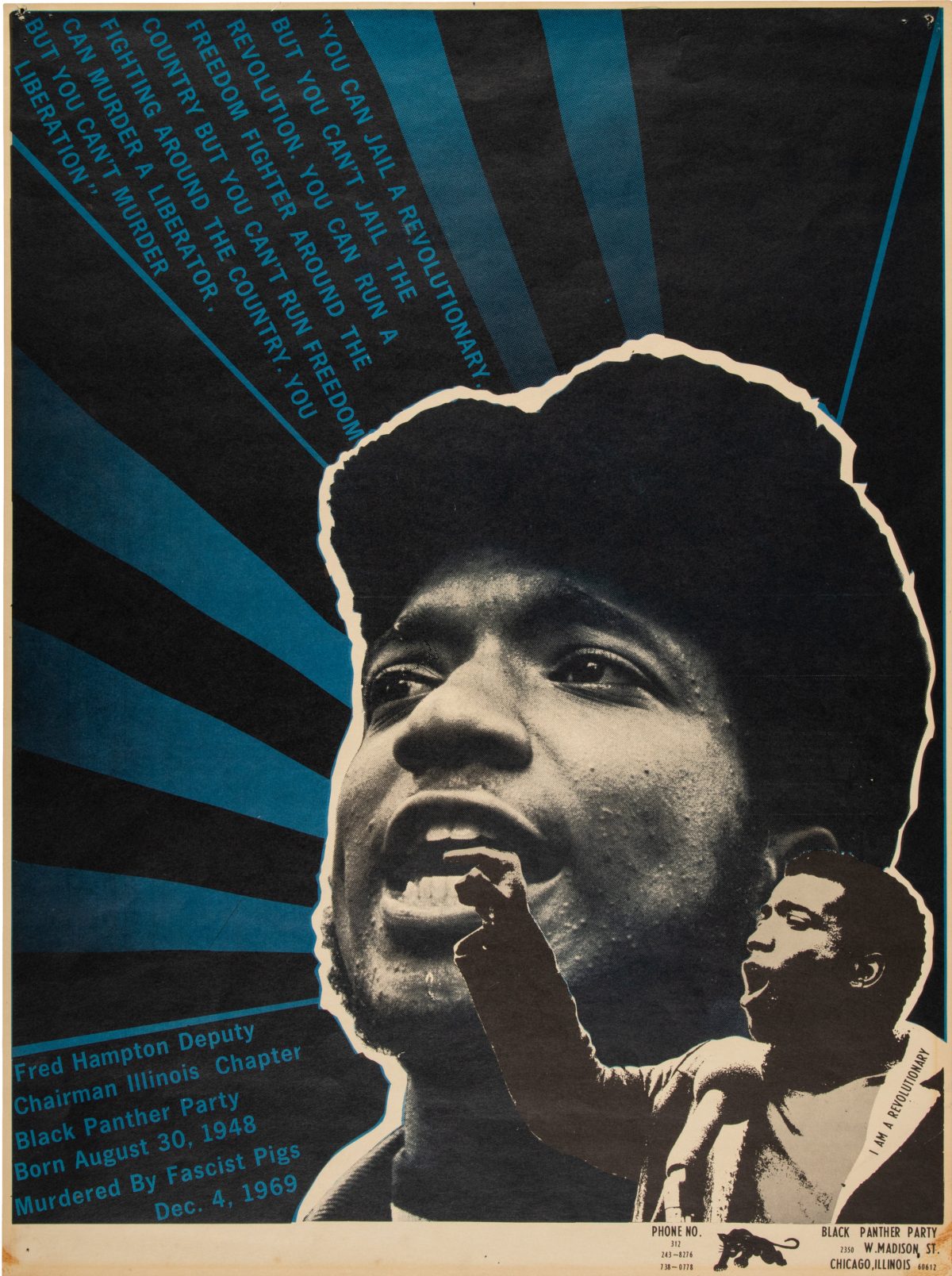

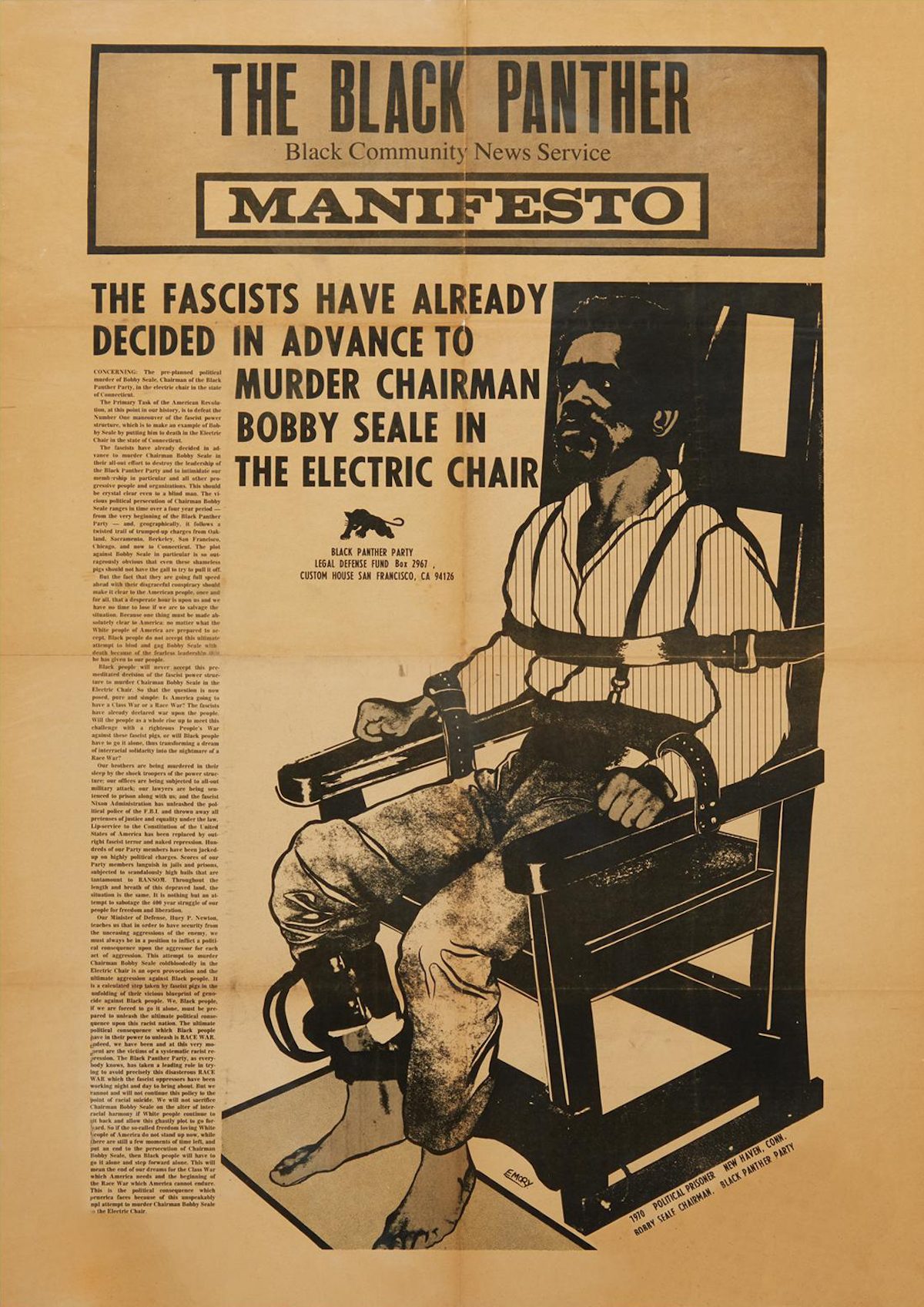

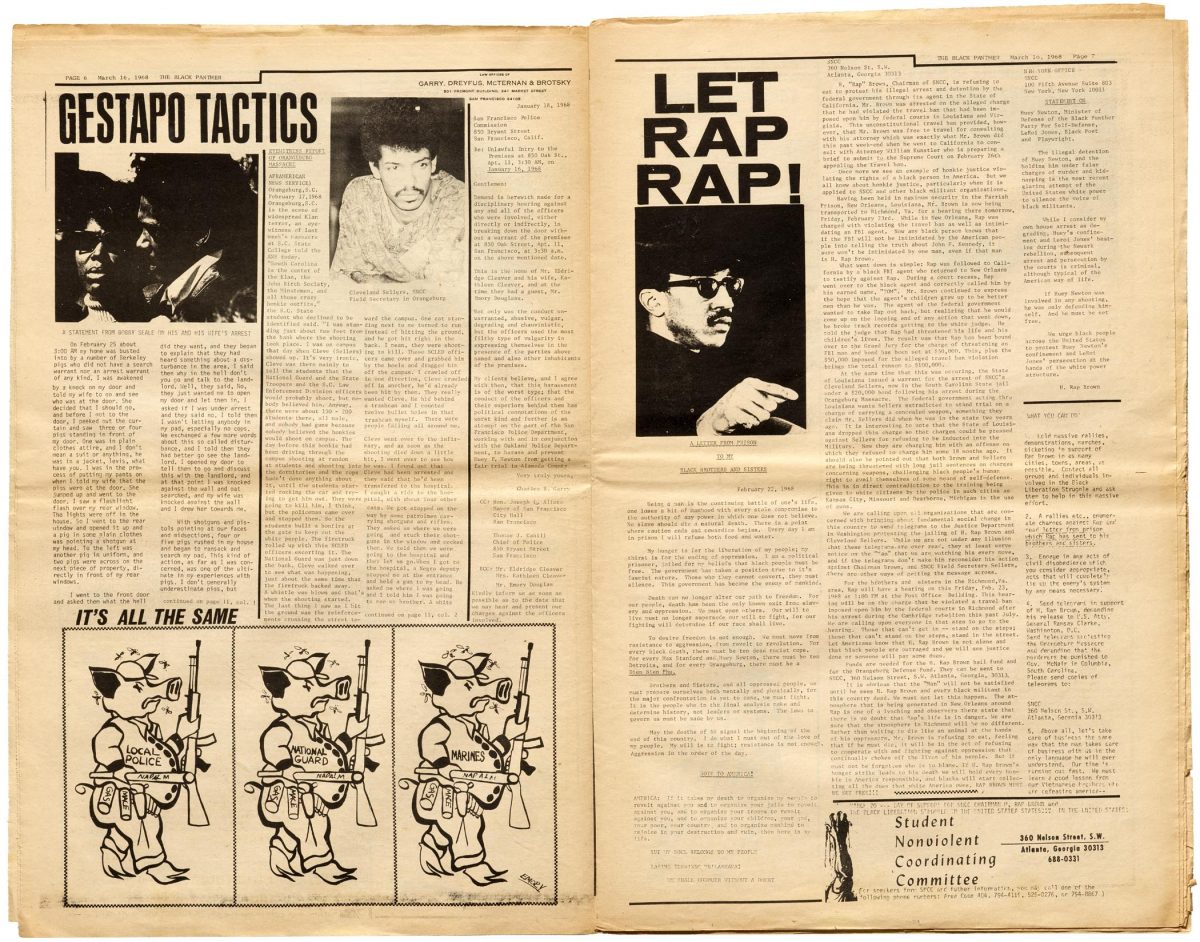

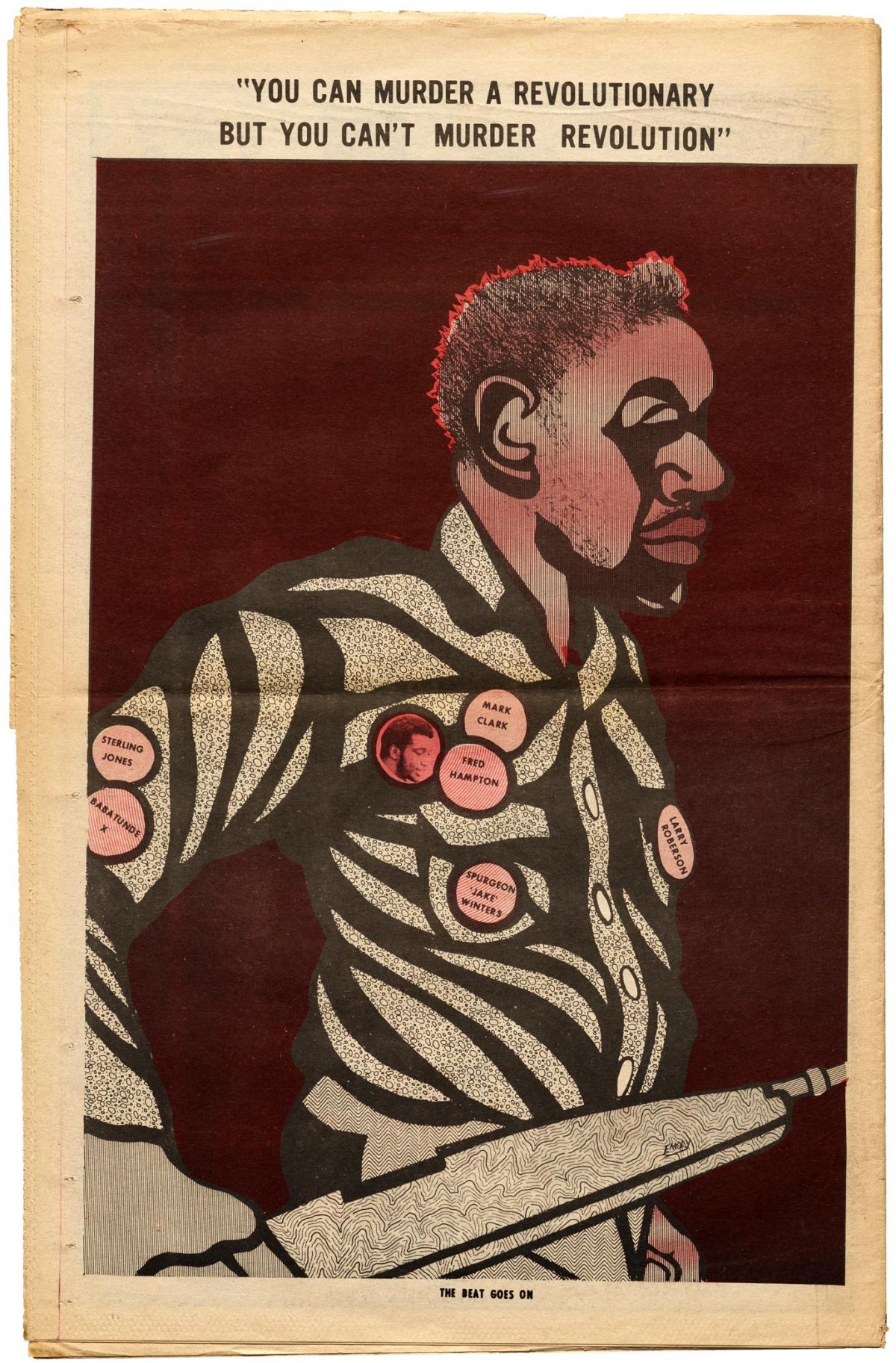

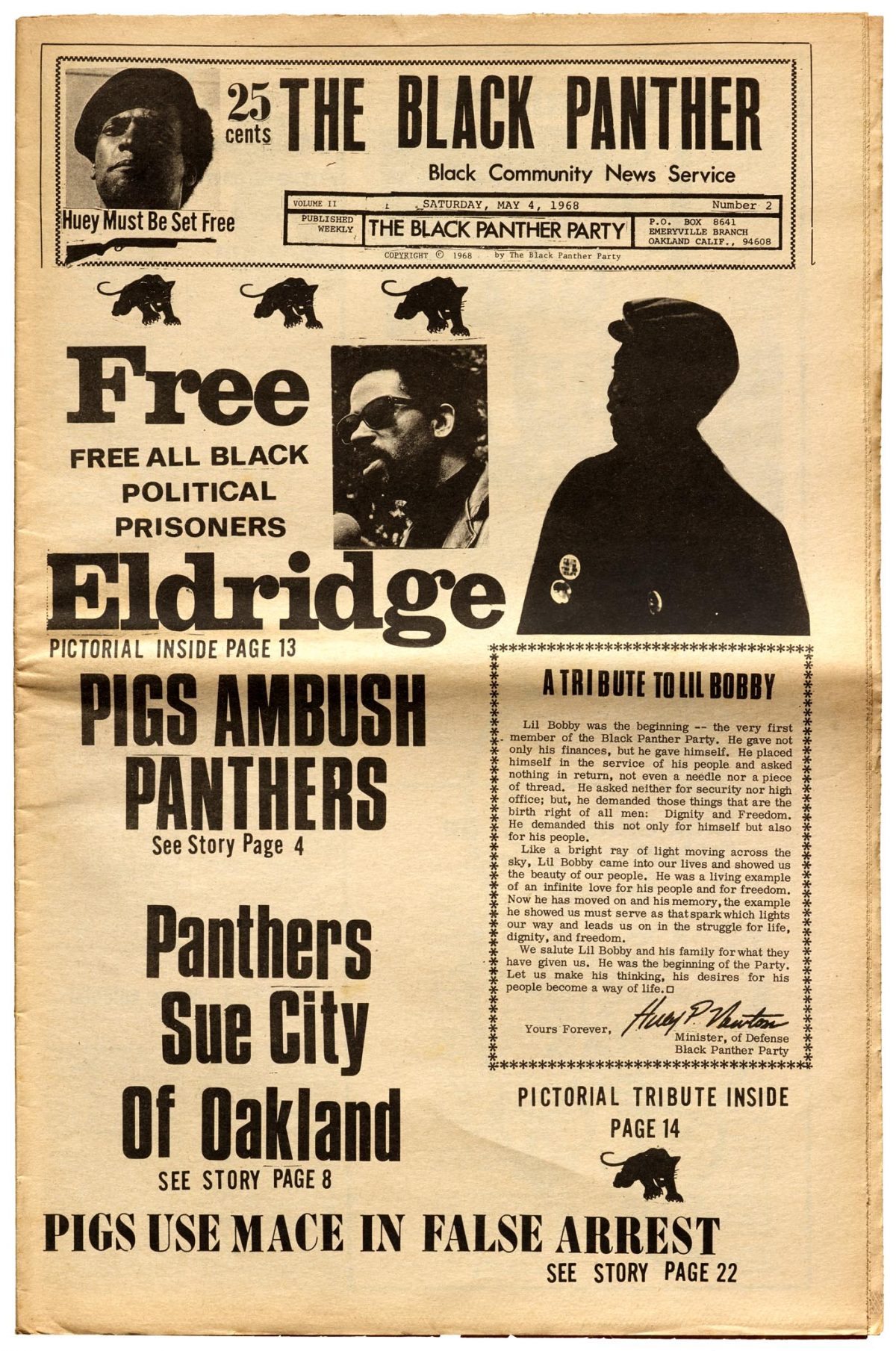

First introduced to graphic design while serving a stint in juvenile detention, Douglas went on to study commercial art and design at San Francisco City College. Inspired by the Panther’s revolutionary vision, he became the party’s Minister of Culture and Revolutionary Artist, given the responsibility of educating and mobilizing the masses through images. The Black Panther ran from 1967 to 1980. “There were news stories and critical essays from party leaders,” notes San Francisco’s Letterform Archive, who hold over a hundred issues dating from 1967-1972, “but it was Douglas’s graphical contribution, in the form of cartoons, collages, and a full page illustration on each back cover, that struck a chord with the broadest audience.”

The readership for The Black Panther was broad indeed.

At its height, from 1968 to 1971, The Black Panther was the most widely read Black newspaper in the United States. In fact, it was among the most widely distributed publications of any kind, reaching a peak weekly circulation of more than 300,000, rivaling the major newspapers of most US cities. It was eventually distributed internationally, with multiple centers in the US, anchored by the main center in San Francisco. All this despite the FBI’s continued efforts to shut down the paper and the party. Douglas recalls the threats on the paper; lawyers had to accompany the deliveries from the press to the airport.

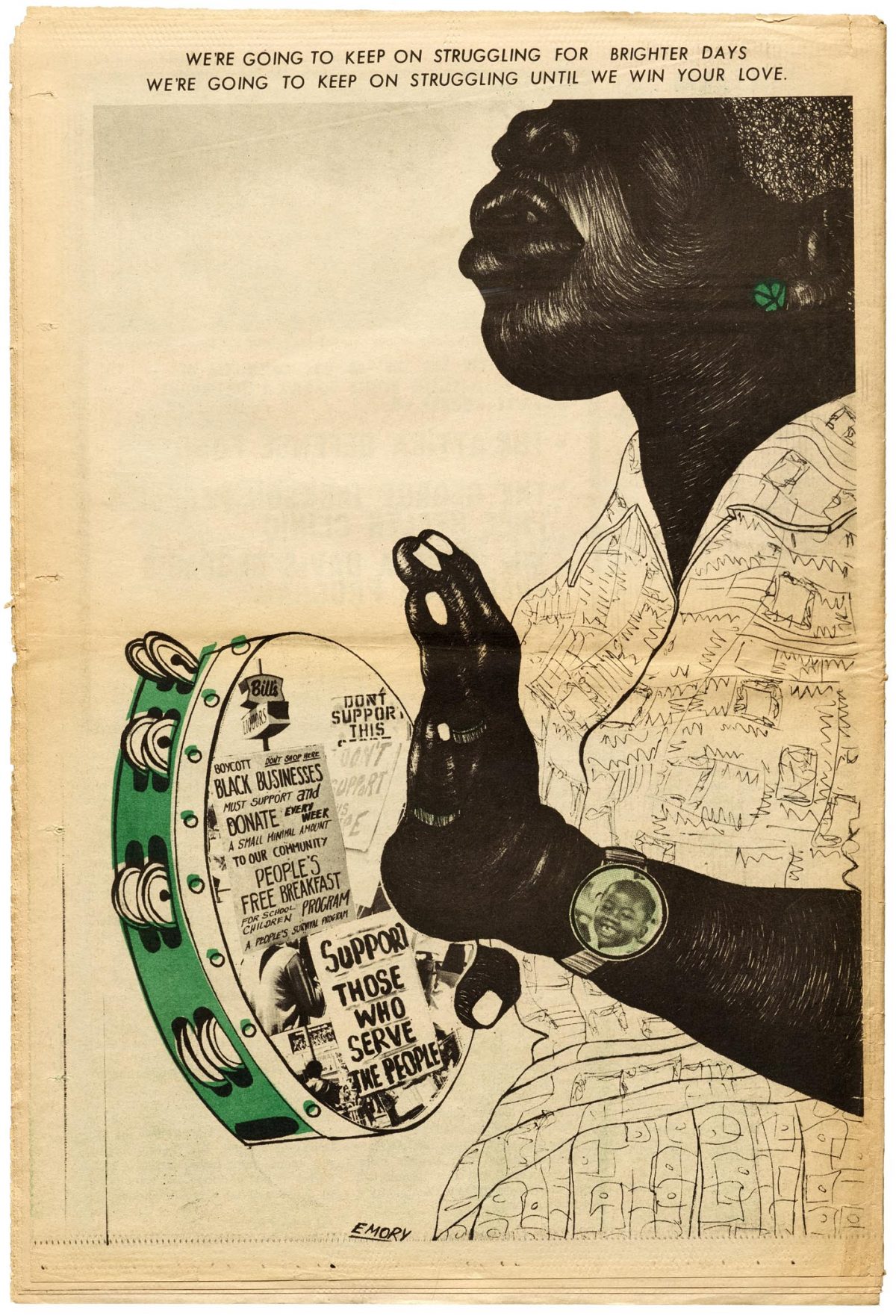

Serving as the paper’s editor and art director, Douglas made many virtues of necessity, creating bold designs from simple tools. “Initially, wherever we were set up, [usually someone’s home], that would be our production area” he says. “We used regular tables, regular lights, Elmer’s glue, rubber cement. We cut and pasted. We made up our own layout sheets. Non-repro blue markers. A lot of it was done on [an IBM Selectric] typewriter.” The images Douglas produced would often later appear as posters and flyers. The Black Panther was printed by Howard Quinn Printers in San Francisco and appeared every Wednesday evening at 25 cents an issue.

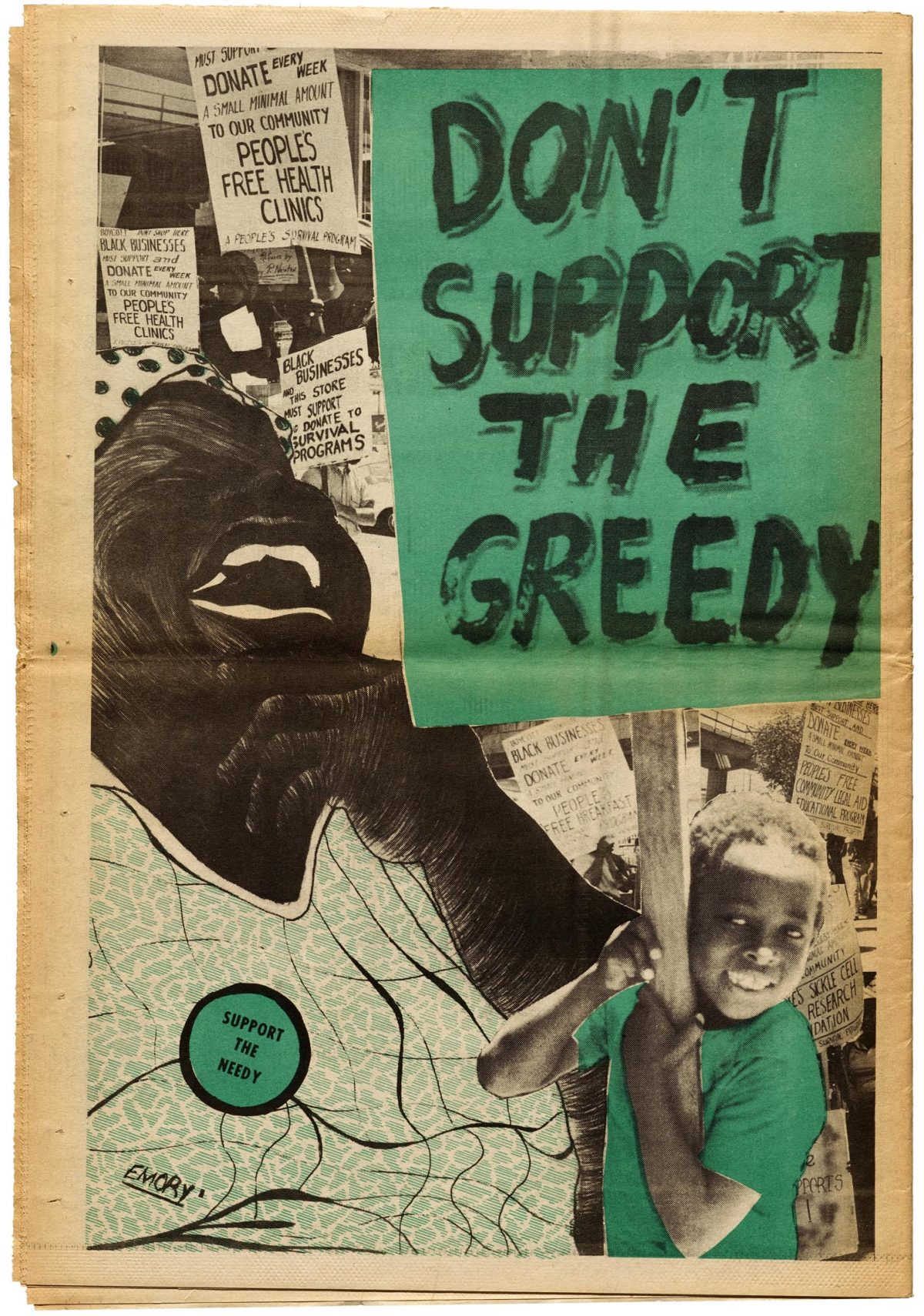

The initial idea behind the paper was to inform and to enlighten and to educate people about the basic issues in the community and to tell our story from our own perspective. We had an X-acto blade, some white sheets of paper, and we would typeset [the pages] on the typewriter with the ball. We couldn’t hardly afford but one color ink and so it was black with one other color. . . To get that bold, broad look, I began to mimic woodcuts with markers and pens, playing with shadows . . . We were creating a culture, a culture of resistance …

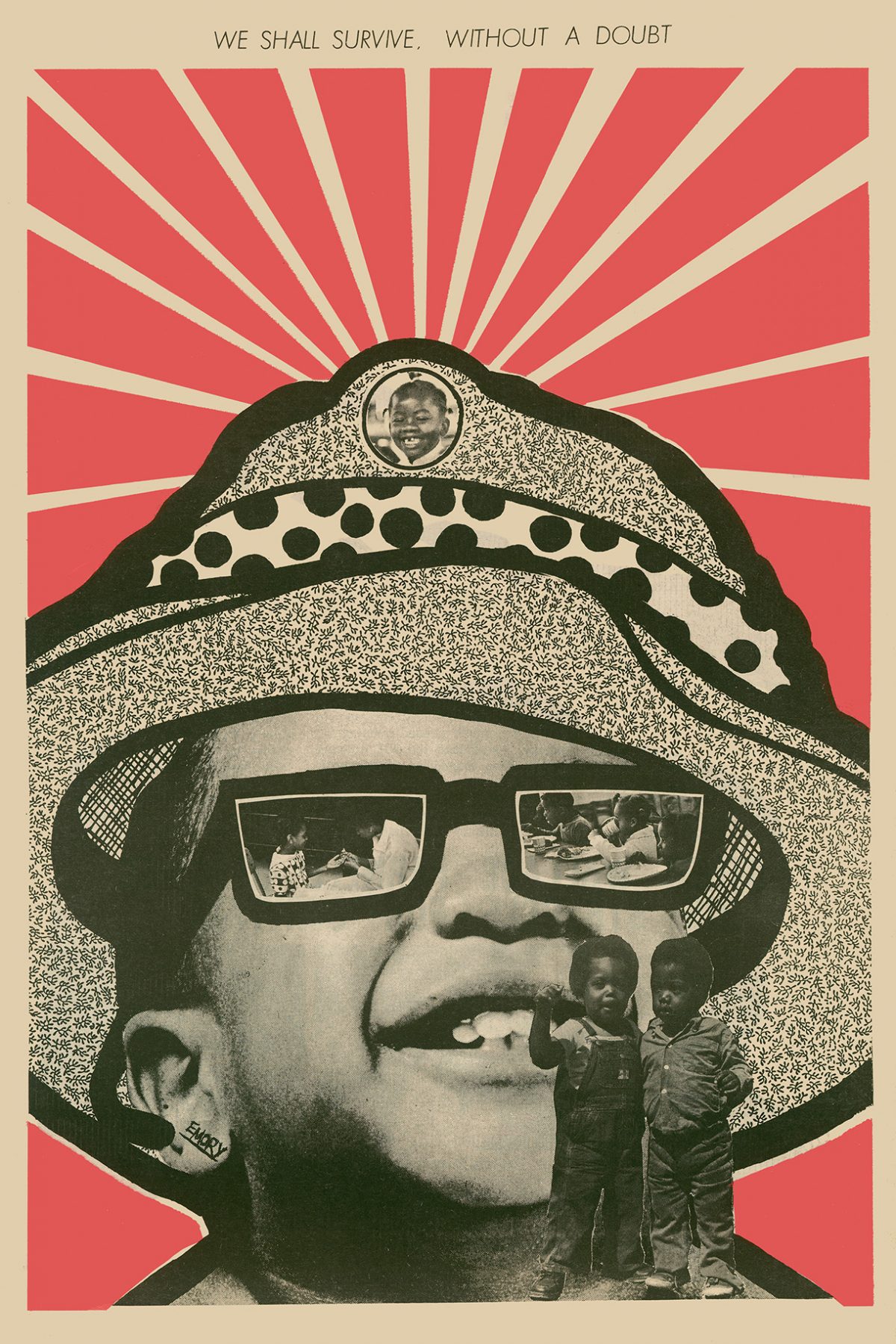

Douglas talks about the importance of conveying the party’s message in clear visual terms, a challenge for every revolutionary artist charged with communicating to people who have often been denied a decent formal education. “At that time the African American community was not a large reading community. They learned from observation and participation. So we had a lot of visuals that they could identify with. Photographs and short captions, as opposed to long, drawn-out essays and editorials. They were visual interpretations of the conditions people lived in…. combined with revolutionary imagery.”

The paper represented a huge shift at the time. “Douglas and Black Panther leaders provided an alternative reality to the popularly mediated image of the US,” writes Colette Gaiter for Minneapolis’s Walker Art Gallery. In the dominant media, “everyone was white, middle class, employed, with their basic needs met by full participation in society.” Such imagery was completely alienating to large segments of the U.S. population; Douglas portrayed the realities of black life without condescension or sentimentality, imbuing his figures with dignity and substance. “Along with an honest picture of poverty, Douglas and the Black Panthers tried to visualize an alternative existence that considered black response to world events that did not represent their interests.”

Fighting a multi-pronged war against brutality at home and imperialism abroad, the Panthers also included a 10-point vision for a society in which black Americans would not be subject to the exploitation and malignant neglect and abuse of corporations and government. Douglas’s art increasingly began to reflect the Panthers’ shift toward building breakfast, lunch, and grocery programs, schools, and health initiatives, many of which became standard programs of government reform throughout the 70s and 80s. The strident militancy and righteous outrage of his work was matched by hopefulness and even joy and celebration in the paper’s drawings and collages.

The Black Panthers may be defunct, but Emory Douglas is still at it. In 2015, he was recognized with the American Institute of Graphic Arts Medal, “for his fearless and powerful use of graphic design in the Black Panther party’s struggle for civil rights and against racism, oppression, and social injustice.” He credits the power of his creative legacy to the people: “It wasn’t that the art came through me or by me,” he remarked on the 50th anniversary of the Black Panther Party’s founding. “It was a collective interpretation and expression from our community.”

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.