“Wilfred Sätty staged huge parties where socialites and hippies mingled, in a subterranean basement of the pre-earthquake building where he lived on Powell Street. He had converted the basement into a surreal environment that resembled a cross between Mrs. Havisham’s parlor in “Great Expectations” and something out of Luna Park….. The basement was divided into a warren of variously weird compartments like the different rooms in Hesse’s Magic Theater. The building had almost as many levels, and ladders, as a Hopi Indian pueblo – a ladder from the second floor to the attic; another that afforded the only access to the basement; a third that led from the basement to a musty, windowless chamber on a kind of mezzanine that was like a movie-set version of an alchemist’s library, lined with ancient books and presided over by a human skull.”

– Thomas Allbright on Wilfred Sätty – Another Ghost of the ‘60s is Gone, San Francisco Chronicle, Feb. 2, 1982.

It’s said the gothic, turn-of-the-century illustrations of Art Nouveau inspired the psychedelic art of the 60s. Artists like Aubrey Beardsley, Harry Clarke, and the Vienna Secessionists paved the way for the posters of the Grateful Dead. But how did this happen? One link in the chain of influence went by the name of Wilfried Sätty, German occultist, illustrator, and collage artist who moved to San Francisco in the early 60s and “associated with artists and bohemians of the Beat Generation,” as Walter Medeiros writes in the Archive of Counter Culture Art:

In 1966, inspired by the openness and creativity of San Francisco’s emergent Hippie culture, he began making pictorial collages. Some of these were sold as poster size prints, which were then very popular. He became a prolific artist, concerned with fine technique and with expression of the broadest range of human experience. He intended his art to engage the imagination and counteract the pernicious stimulus-response programming of media advertising.

Sätty’s method was alchemical, his occult practices defined his life’s work. “Alchemy can be a state of being,” he remarked in a 1970 interview. “There is such a thing as visual or intellectual or artistic alchemy. The undeveloped mind may be considered akin to lead, the fully-realized mind as gold. And the same is true of art. Much of contemporary art is lead.”

Mass media, Sätty believed, had created a “state of mental pollution” in which people “don’t know the difference between the truth and lies.” In order to learn, they must “open up their subconscious.” Surrealism exerted its influence on him, and he studied architecture, engineering, and design, honing his drafting abilities. Born as Wilfried Podriech in 1939, he spent his childhood playing in the bombed-scarred WWII ruins of his native Bremen, a place he called “a big surrealistic playground.”

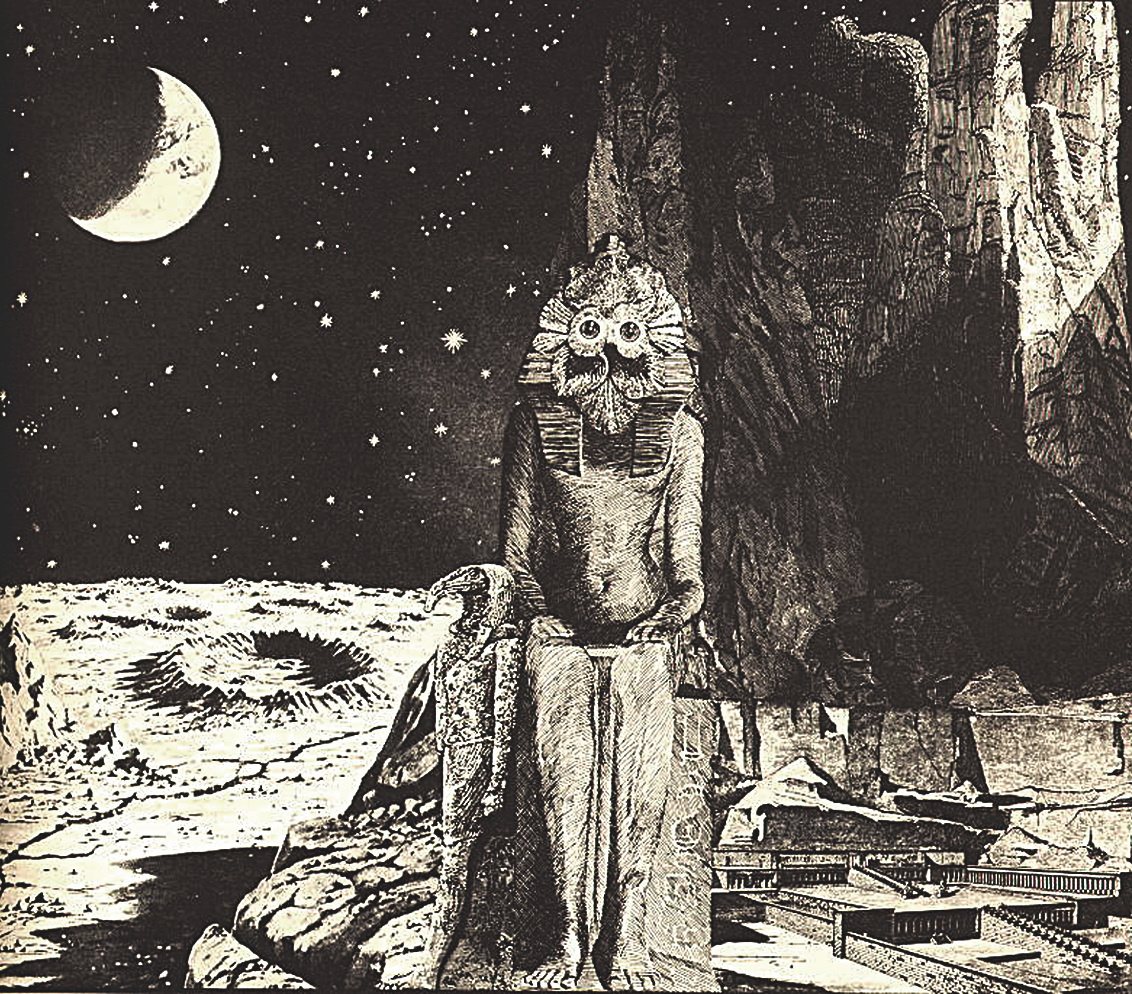

When he came to California, the artist adopted the name Sätty, “intended to be reminiscent of the Egyptian Pharaohonic name Seti,” Jonathan Coulthart notes. “The umlaut over the ‘a’ gives the pronunciation setty.” The linguistic reference was probably lost on most Americans, but Sätty wasn’t interested in being accessible. His goal was the transmutation of contemporary art and design into what he called “another world within our world.” Sounding very much like Aleister Crowley, he claimed that getting there is only “a matter of will.”

Sätty built an alchemical laboratory “in a basement hollowed into the mud under an old frame house near Fisherman’s Wharf,” San Francisco Chronicle art critic Thomas Albright wrote of him after his death in 1982. In its “warren of variously weird compartments,” he gathered, “old lamps, misshapen easy chairs, mannequins and dolls from trash bins in Pacific Heights.”

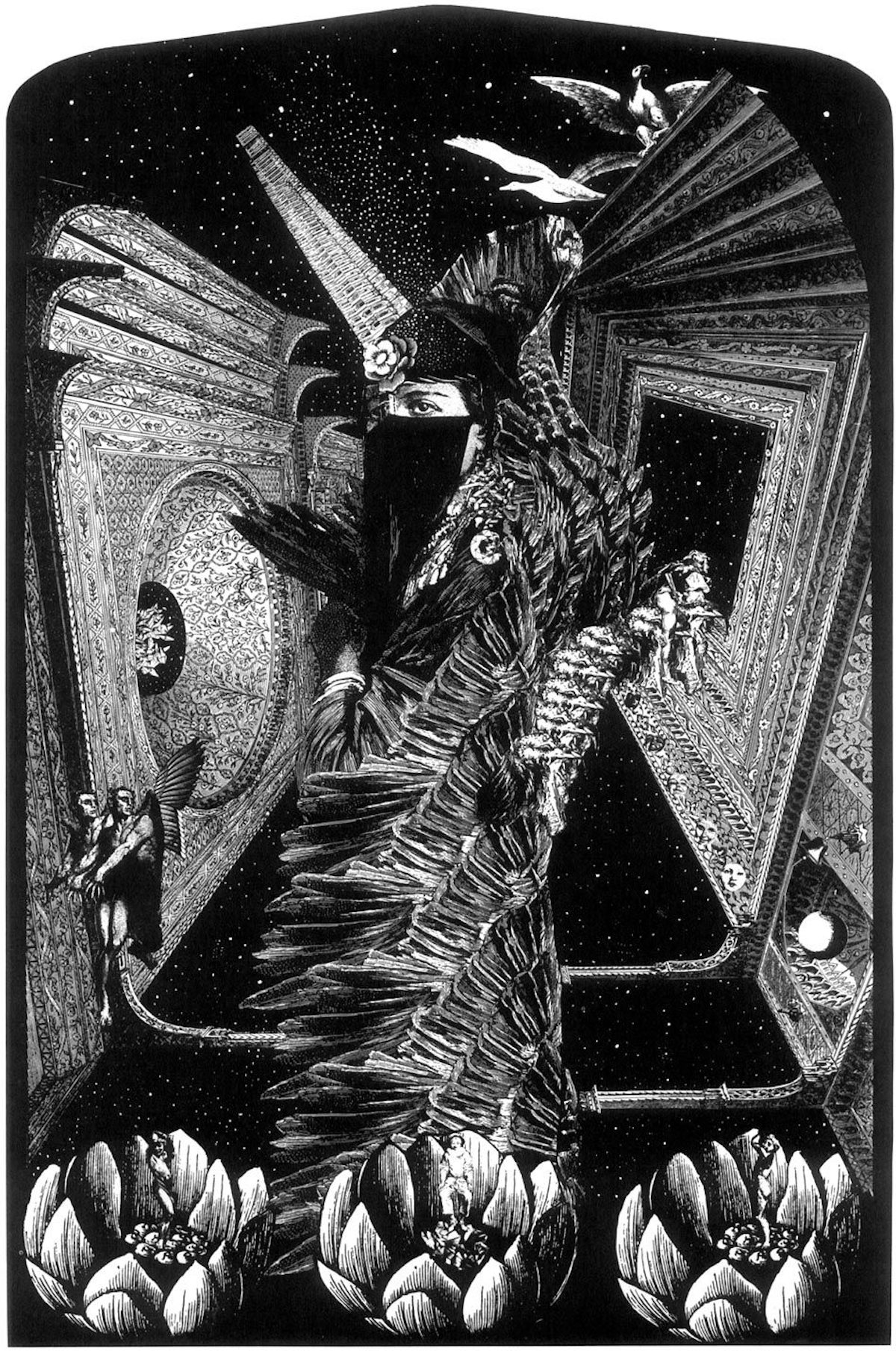

Here, Sätty kept an intense and constantly expanding “image bank,” snippets cut from old engravings, the photographs of contemporary news magazines and every other conceivable source. Sequestered like a medieval copyist in his cell, working with the meticulous perfectionism of a Dutch diamond cutter and the obsessiveness of a paranoiac possessed by an “idée fixe,” Sätty combined and recombined these fragments into often magical collages where it was impossible to tell where reality ended and fantasy began.

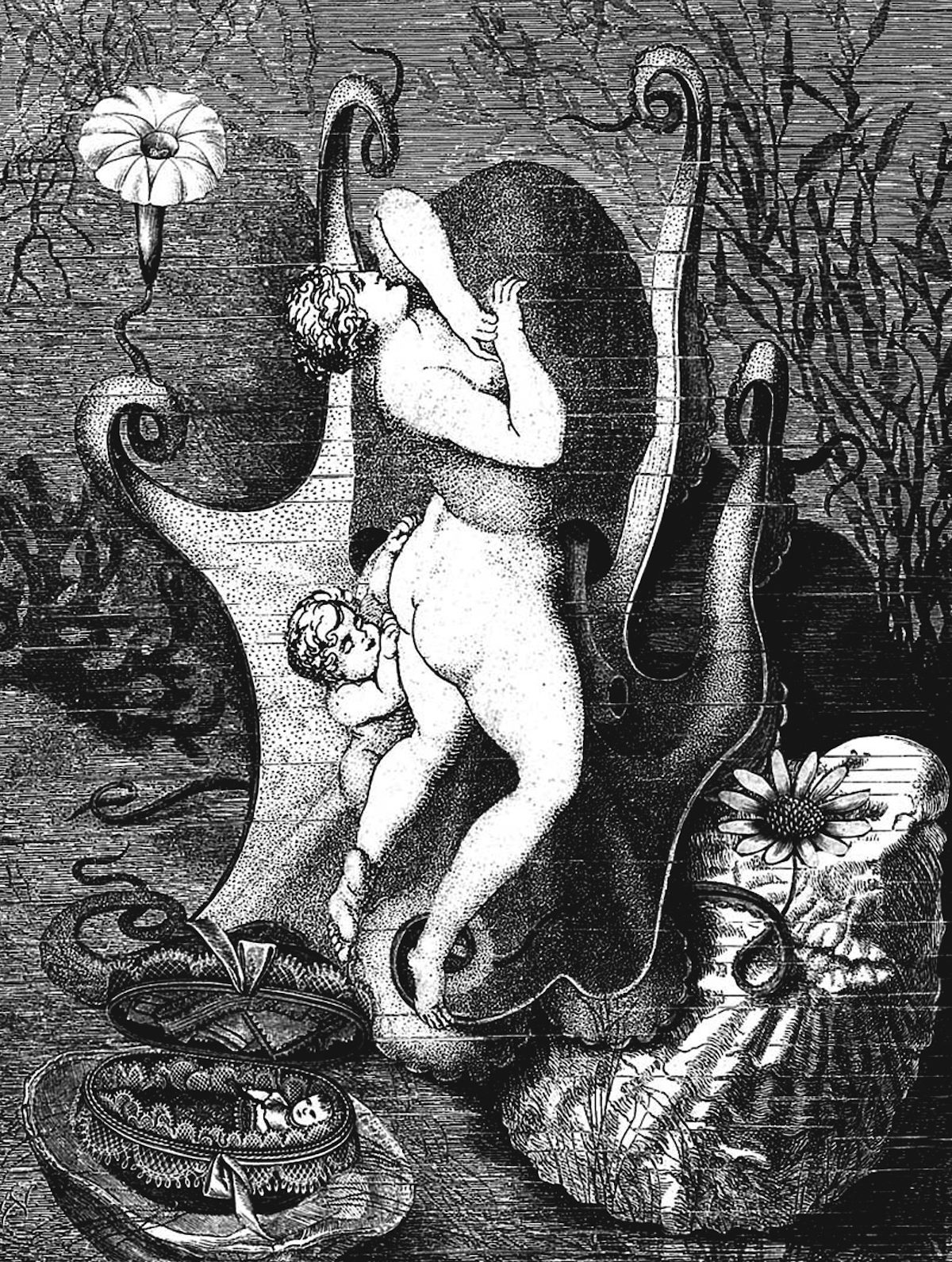

From his junk shop bunker, Sätty helped shape the counterculture, contributing his collages and lithographs to rock posters and album covers. His book illustrations, of Edgar Allan Poe and Bram Stoker’s Dracula, are very reminiscent of artists like Beardsley and Clarke. His first book, The Cosmic Bicycle, was made into a short film by Les Goldman (above) in 1972. Sätty died while falling from a ladder to his attic. He was largely forgotten by that time, living alone in poverty. He had been “fascinated by the grotesque and bizarre,” Albright remarks, “but he was also disheartened by the bland impersonality that he saw overtaking the lifestyles of the 70’s, and there was another side of his art that sought to reflect a primeval kind of innocence, to reconstruct a futuristic Garden of Eden.”

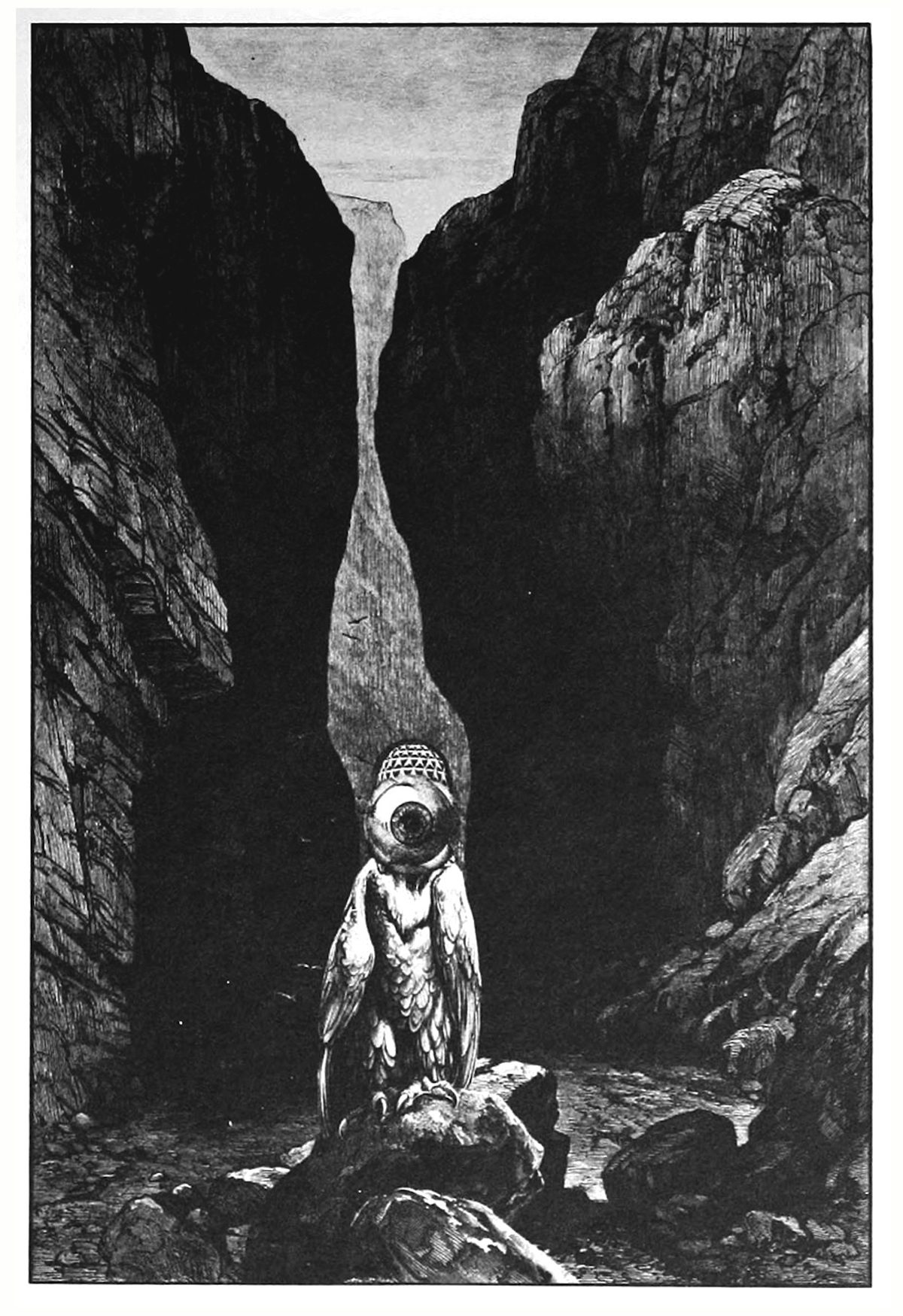

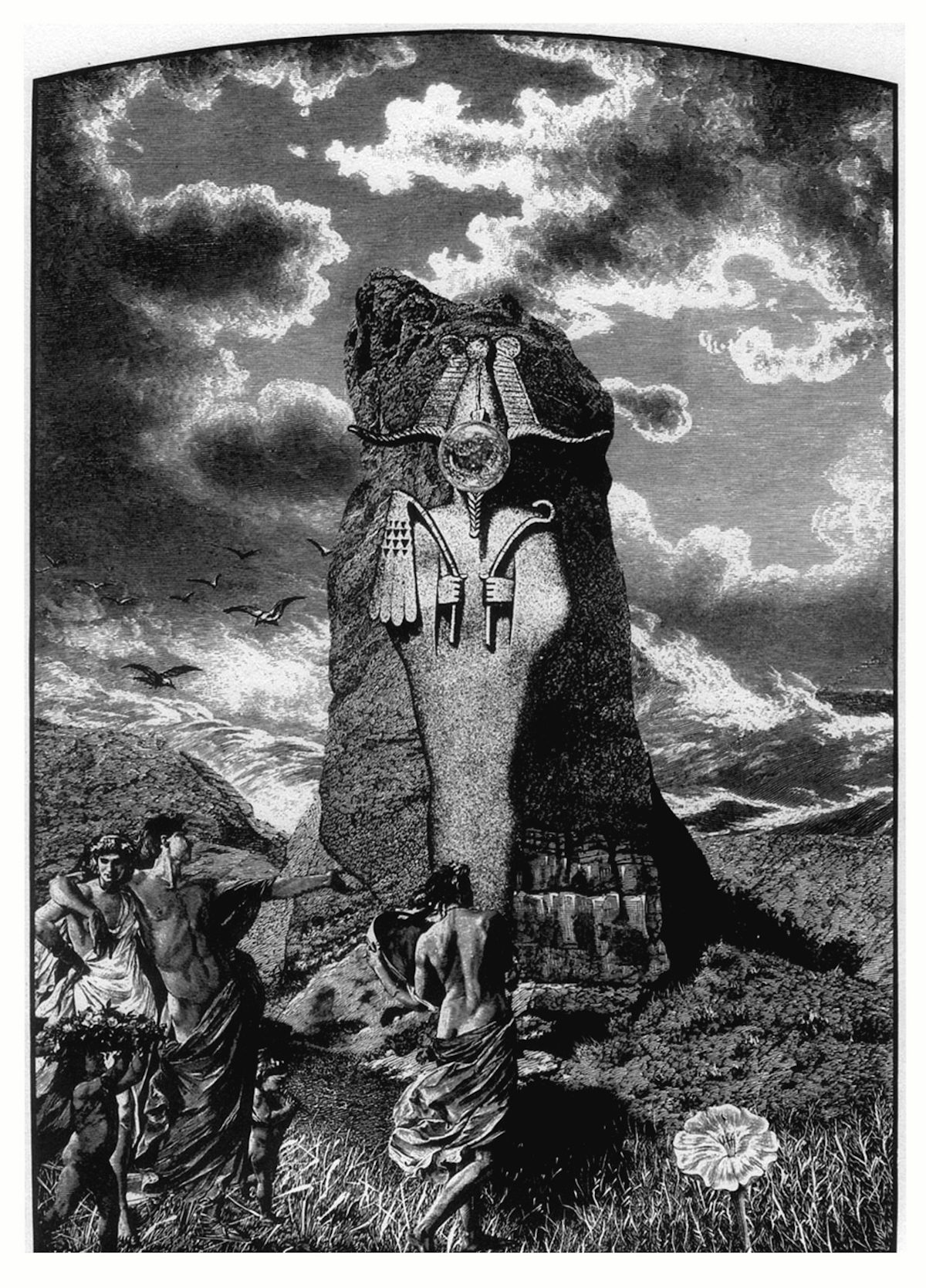

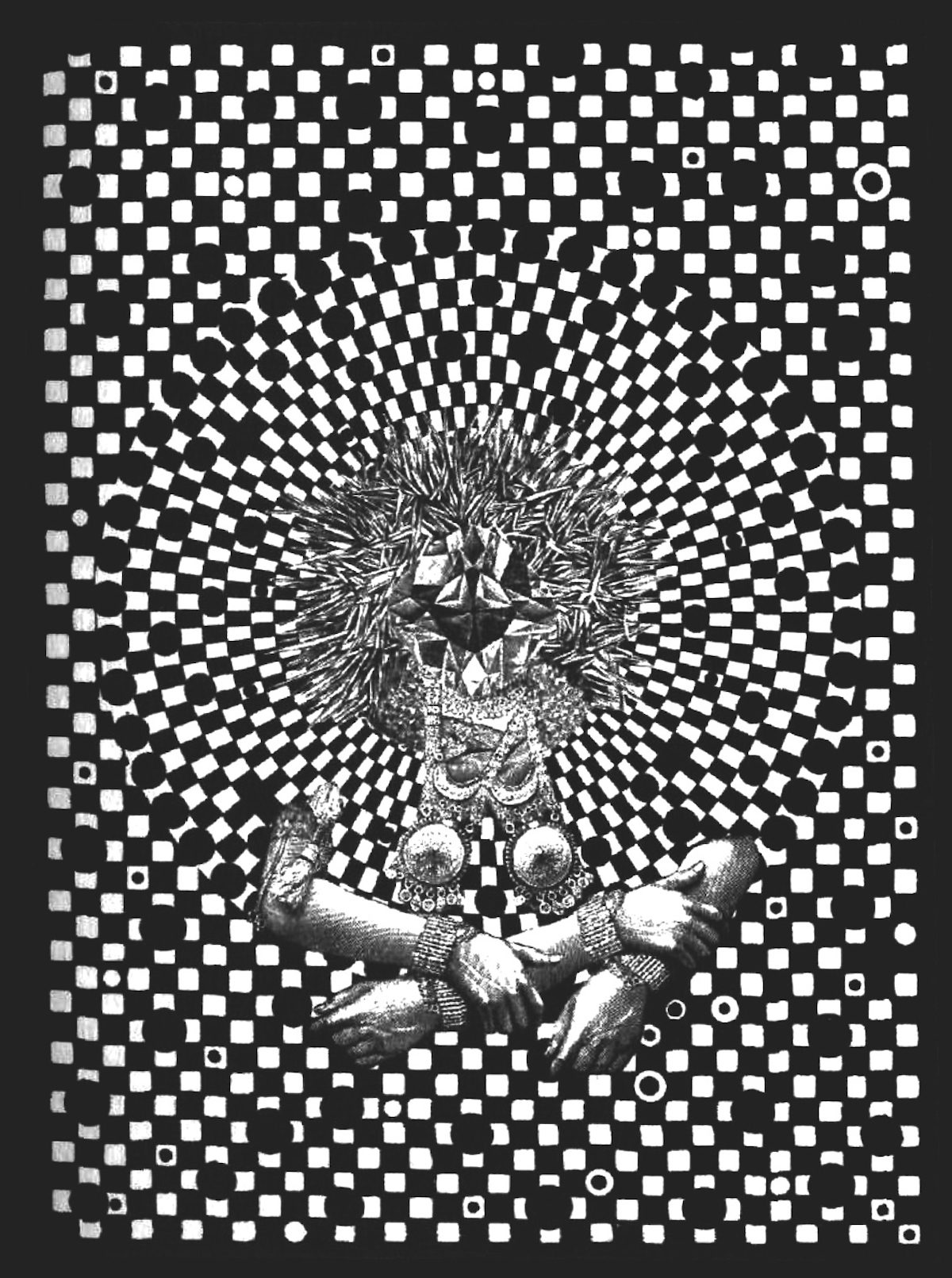

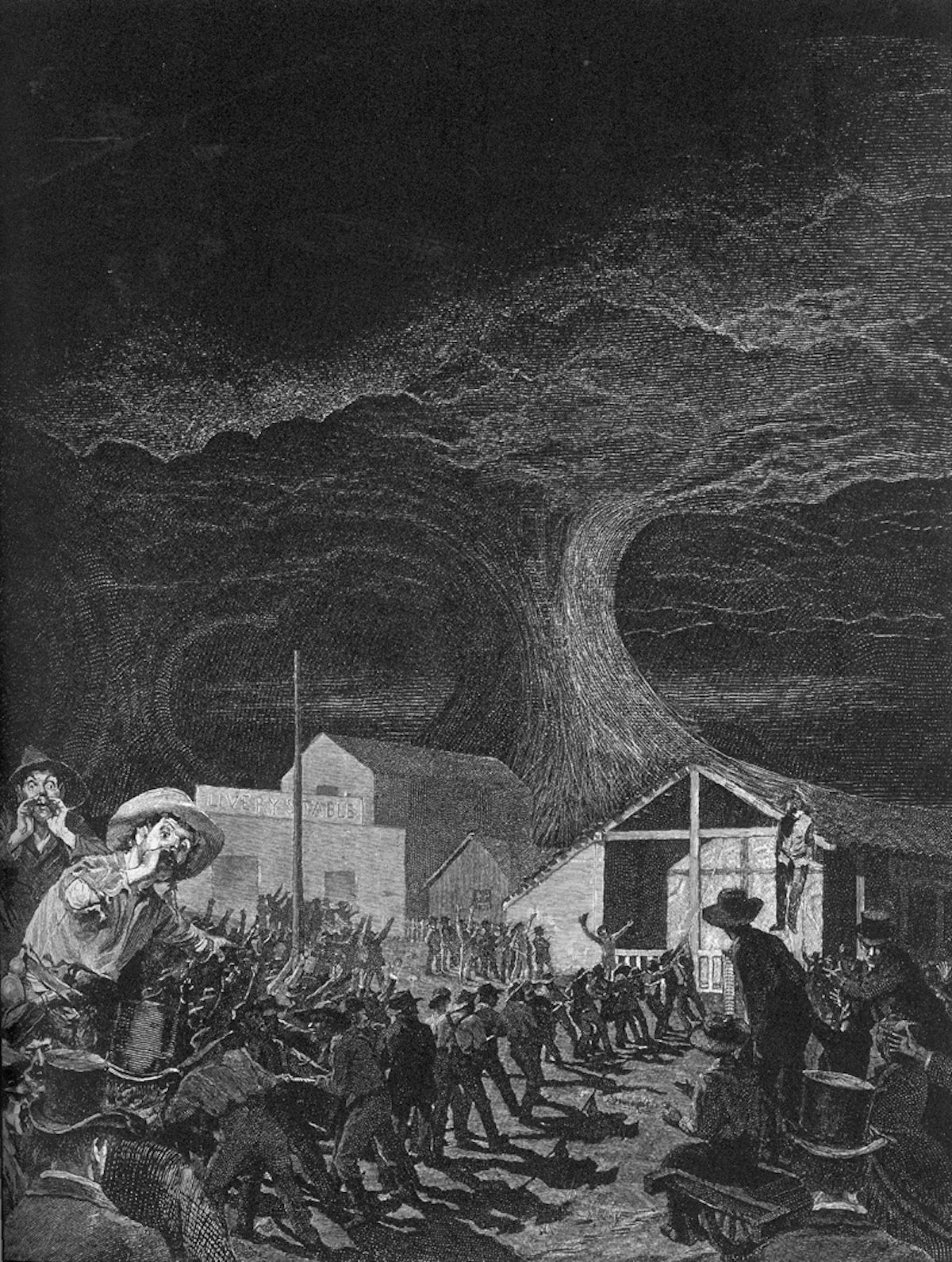

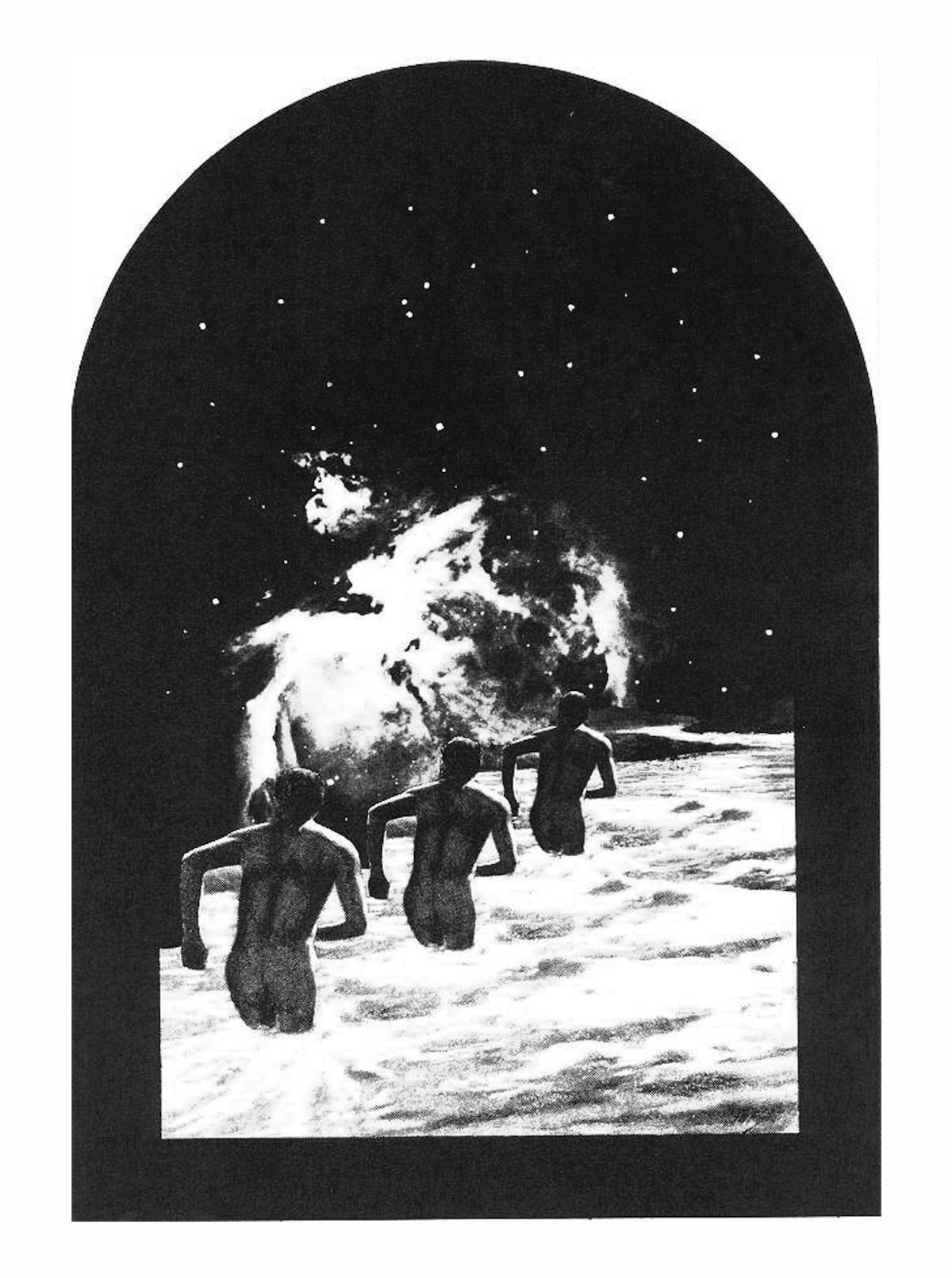

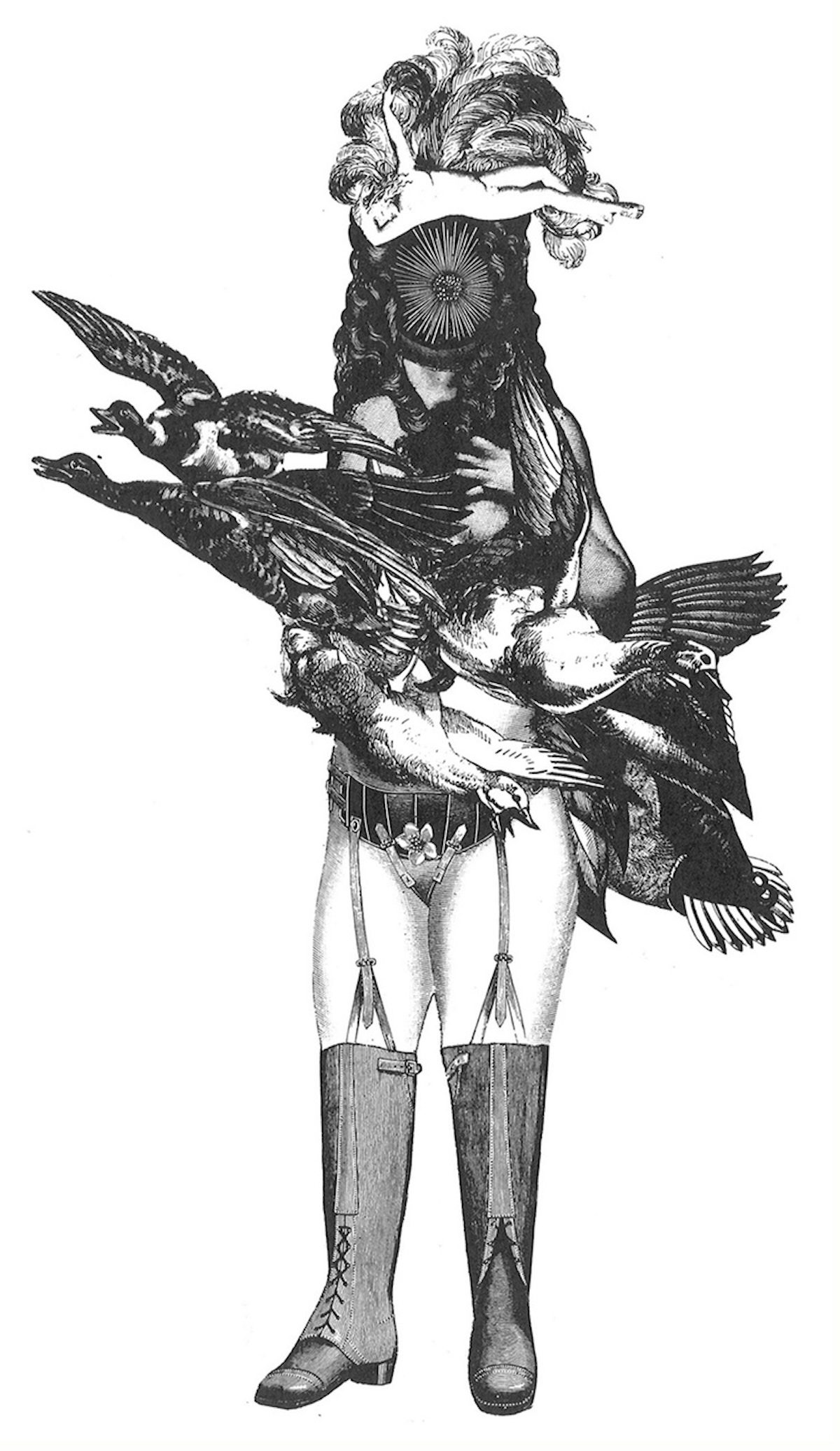

Wilfried Sätty (1939-1982), “The illustrated Edgar Allan Poe”, 1976

Wilfried Sätty (1939-1982), “The illustrated Edgar Allan Poe”, 1976

Wilfried Sätty (1939-1982), “The illustrated Edgar Allan Poe”, 1976

Wilfried Sätty (1939-1982), “The illustrated Edgar Allan Poe”, 1976

Wilfried Sätty (1939-1982), “The illustrated Edgar Allan Poe”, 1976

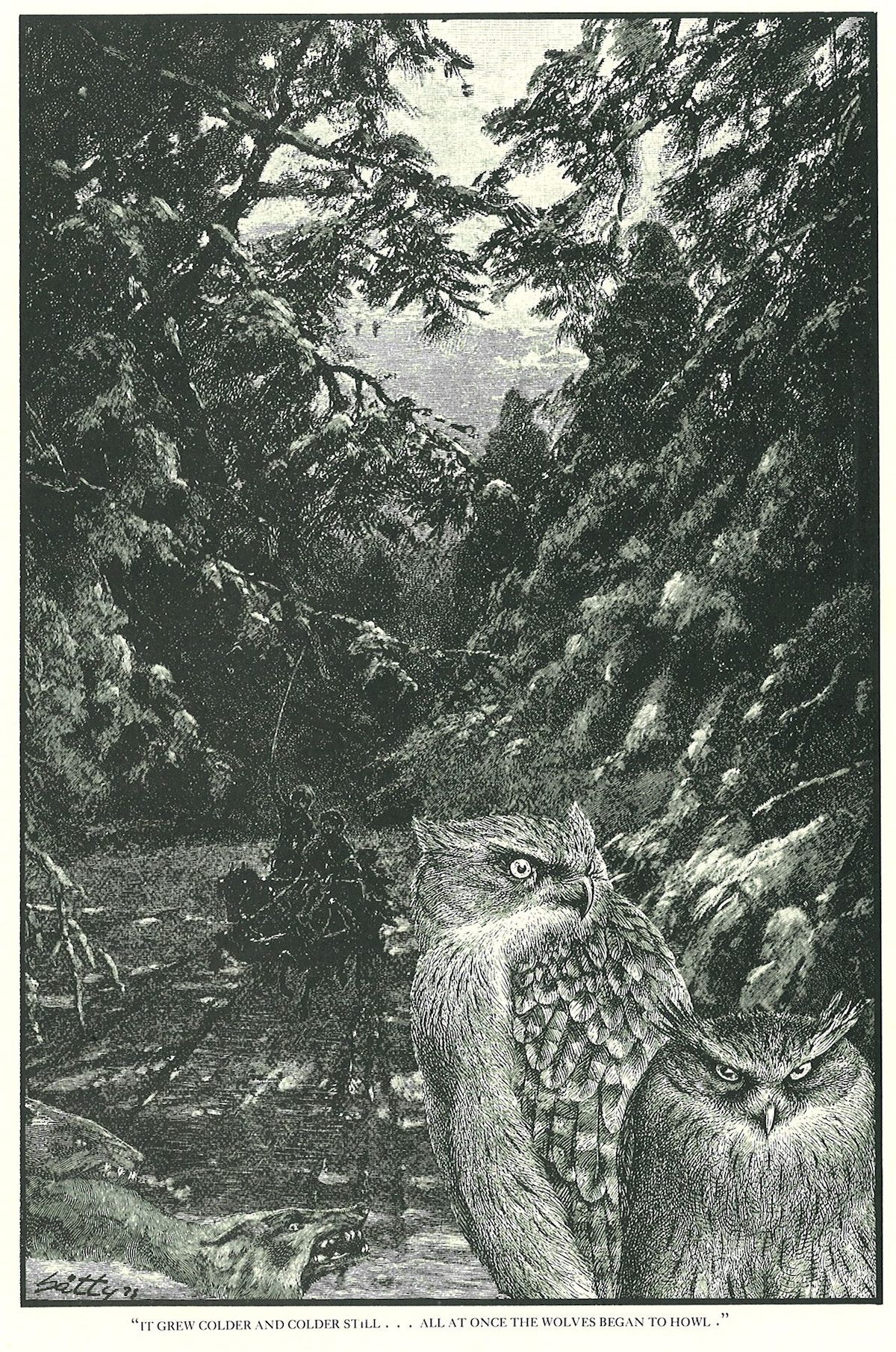

Wilfried “Sätty” Podriech illustration’s from the Annotated Dracula (1975)

Wilfried “Sätty” Podriech illustration’s from the Annotated Dracula (1975)

Wilfried “Sätty” Podriech illustration’s from the Annotated Dracula (1975)

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.