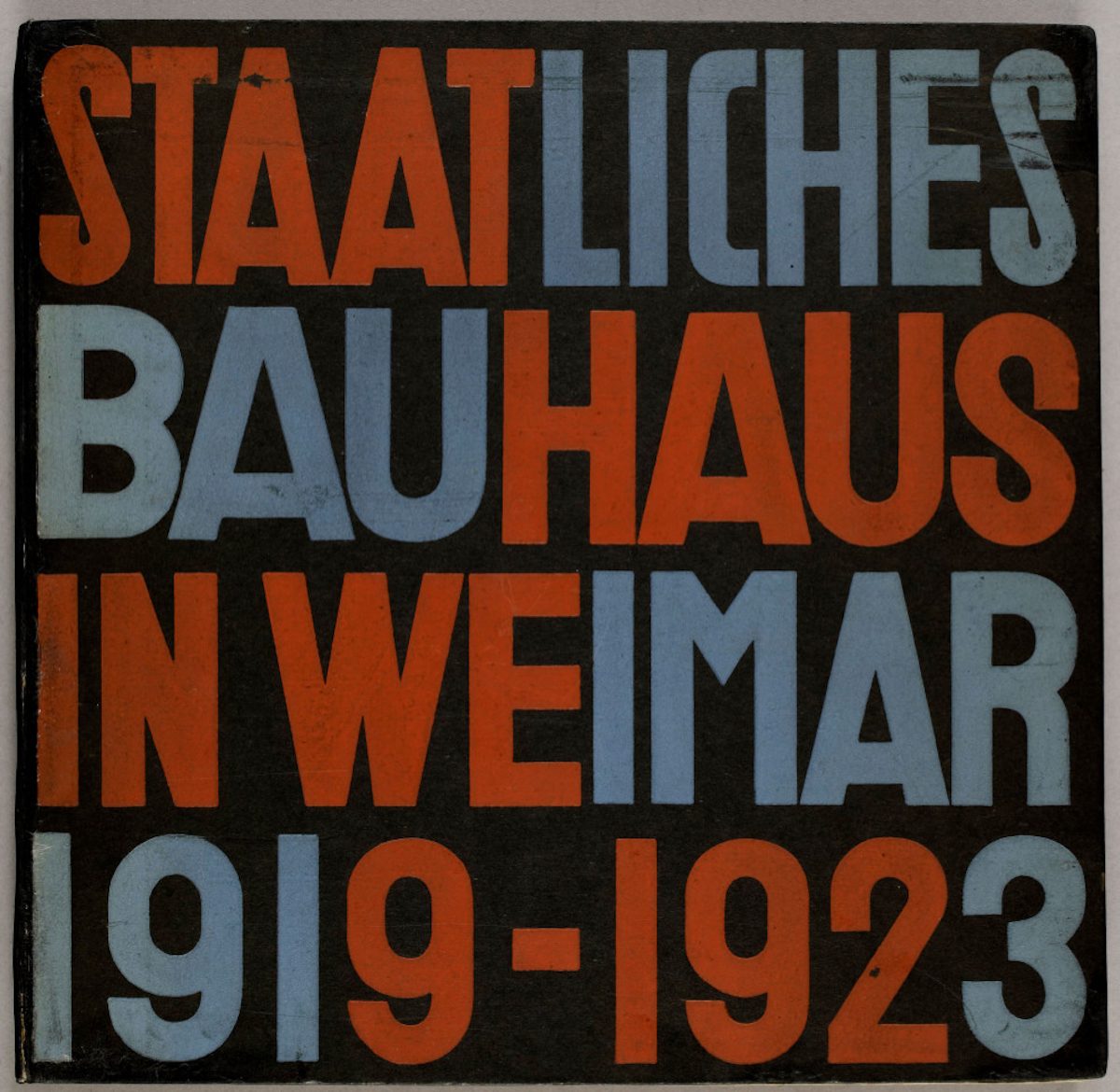

The “ultimate aim of all visual arts is the complete building!” proclaims Walter Gropius in his short 1919 pamphlet “Program of the Staatliche Bauhaus in Weimar.” The German architect and founder of the Bauhaus school called for a unity of arts, crafts, and design, a unity that had been lost, he wrote, in the elevation of individual artists and the modern division of labor. “Today the arts exist in isolation, from which they can be rescued only through the conscious, cooperative effort of all craftsmen.” Architects, painters, sculptors—“all must return to the crafts!”

The influence of the Bauhaus is such that we can take for granted the revolutionary nature of its program, and the considerable resistance Gropius and his colleagues faced as they attempted to modernize design with an eclectic approach drawing from folk art traditions as much as from industrial processes. Their aim – “to create a new guild of craftsmen without the class distinctions that raise an arrogant barrier between craftsman and artist” – threatened those who profited from such barriers. And their approach dismayed critics who saw specialization and technical mastery as the essence of fine art.

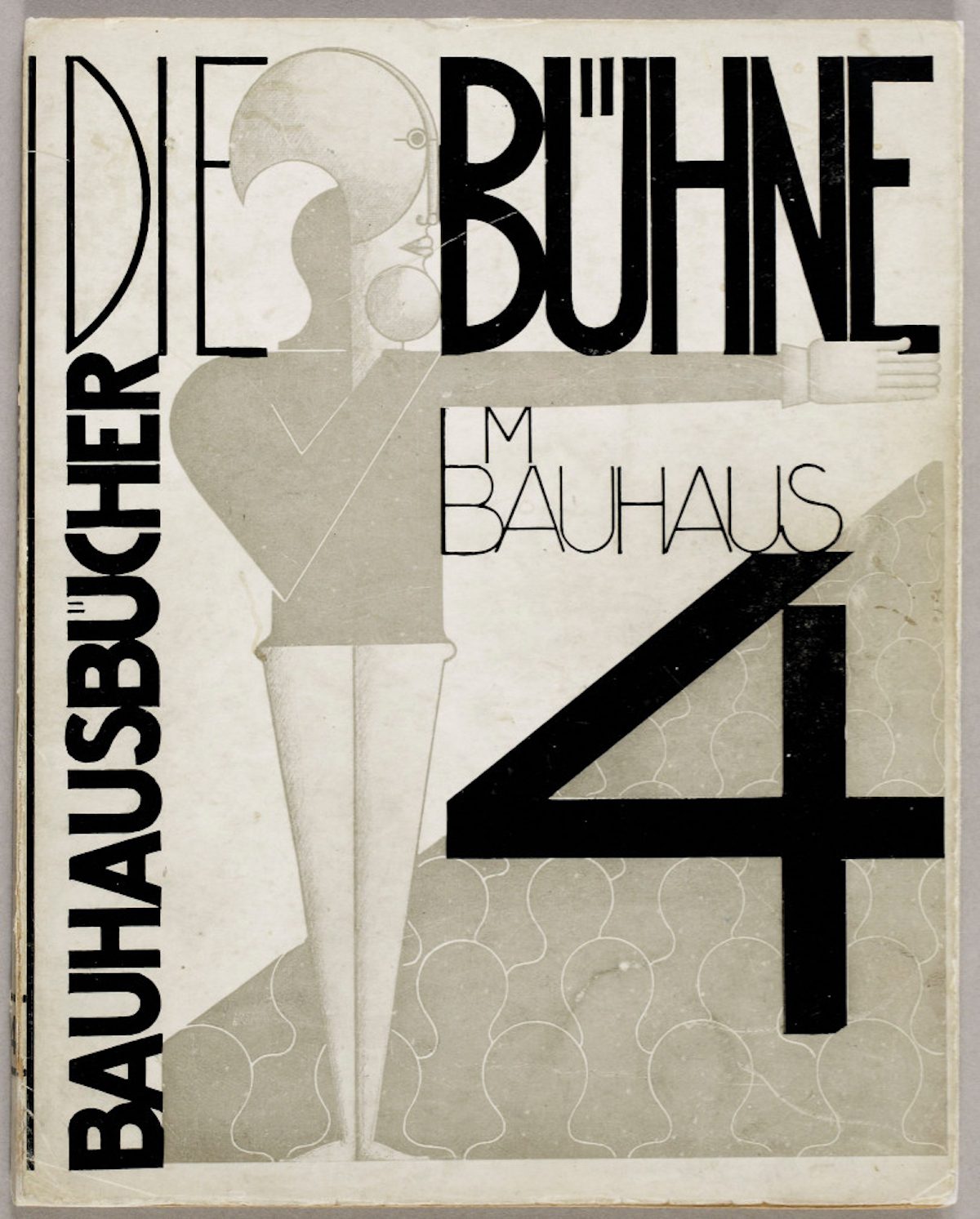

“A key characteristic of work at the Bauhaus was to take unusual paths and explore them for oneself in an autodidactic way,” says Johannes Rinkenburger, author of Visions of the Bauhaus Books. Every artist and instructor at the school made an attempt to work in media besides those in which they were trained. Workshops at the school “included metalworking, weaving, ceramics, carpentry, graphic printing, printing and advertising, photography, glass and wall painting, stone and wood sculpture, and theatre,” Monoskop writes, and the curriculum was designed to “turn out artisans and designers capable of creating useful and beautiful objects appropriate to this new system of living.”

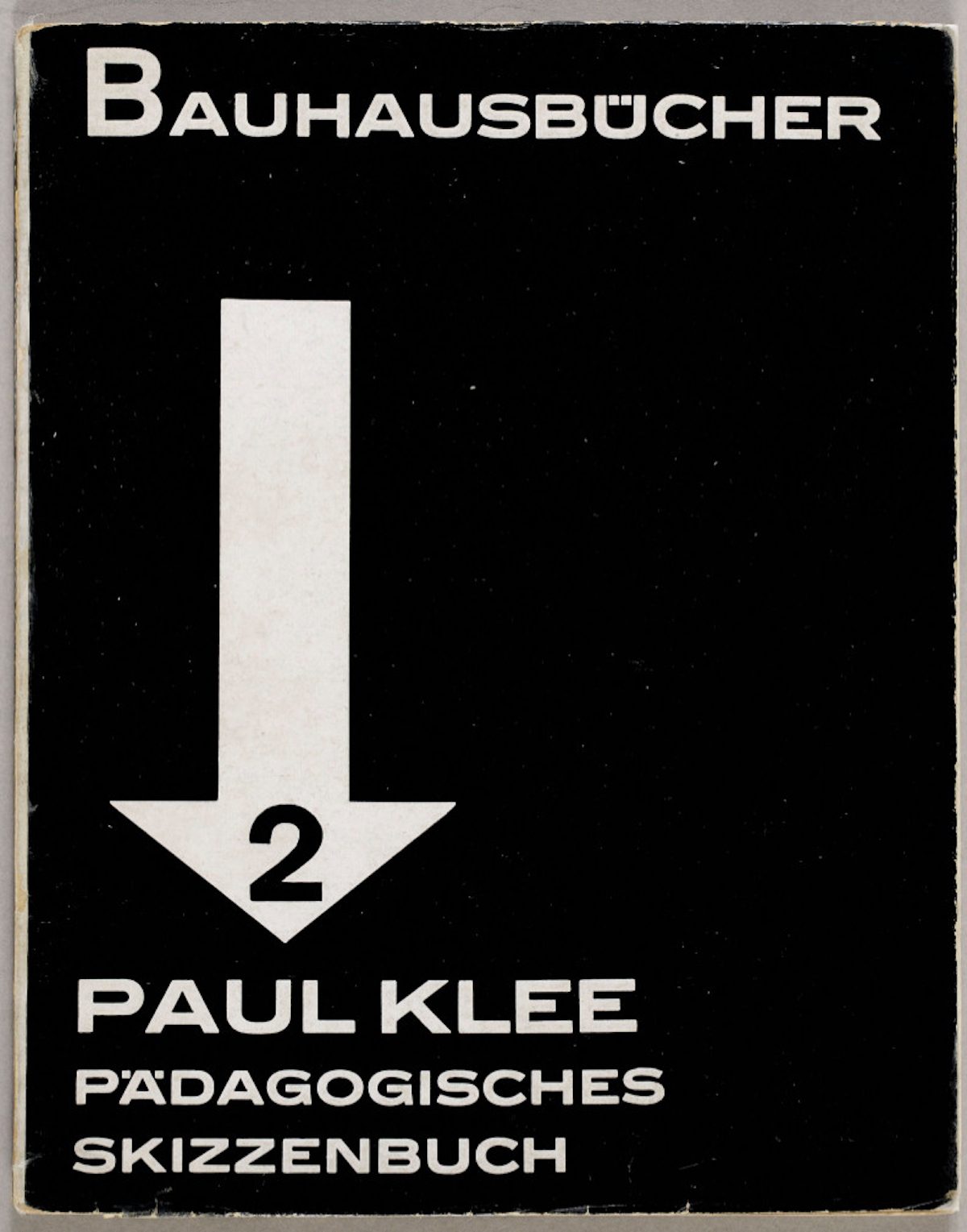

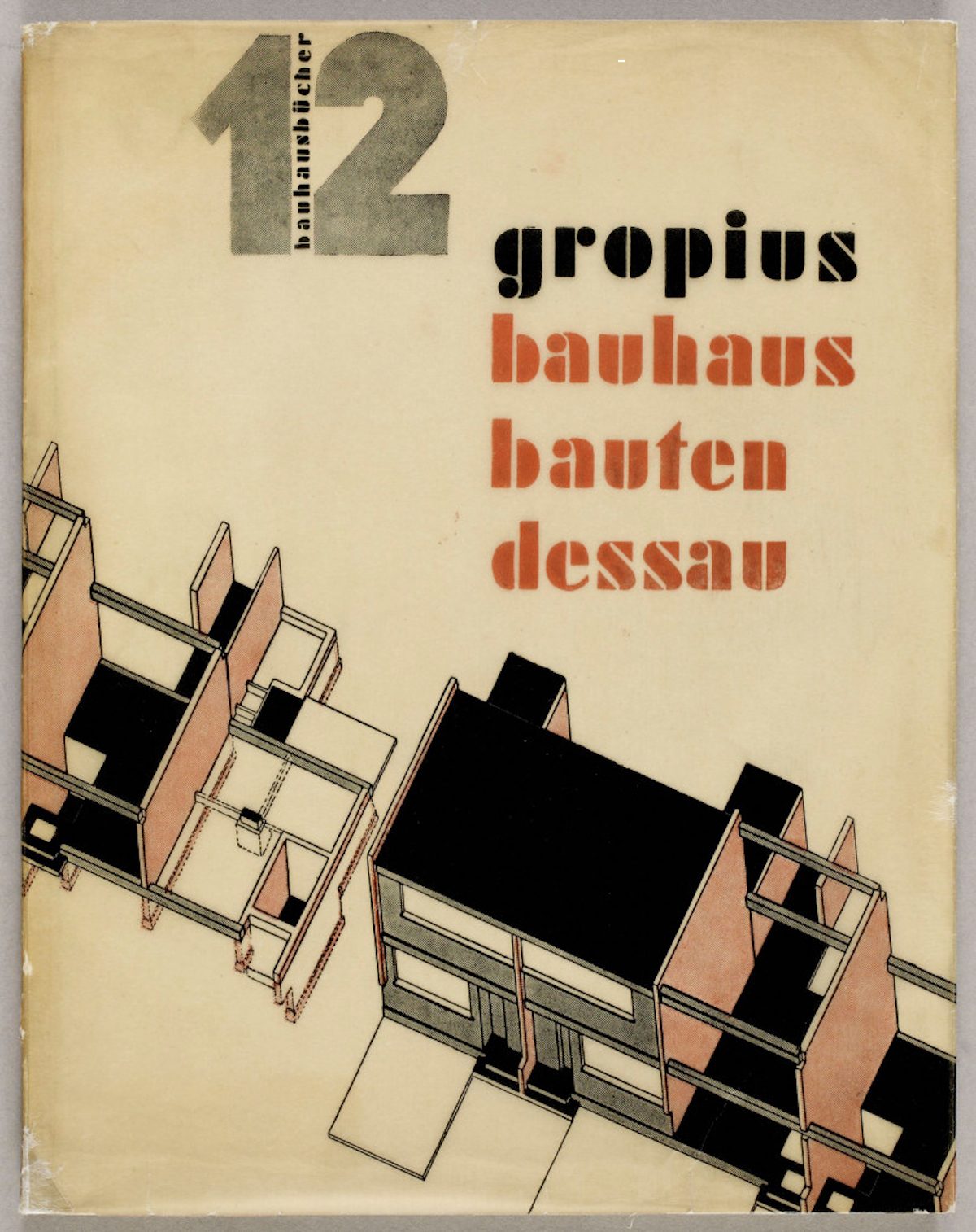

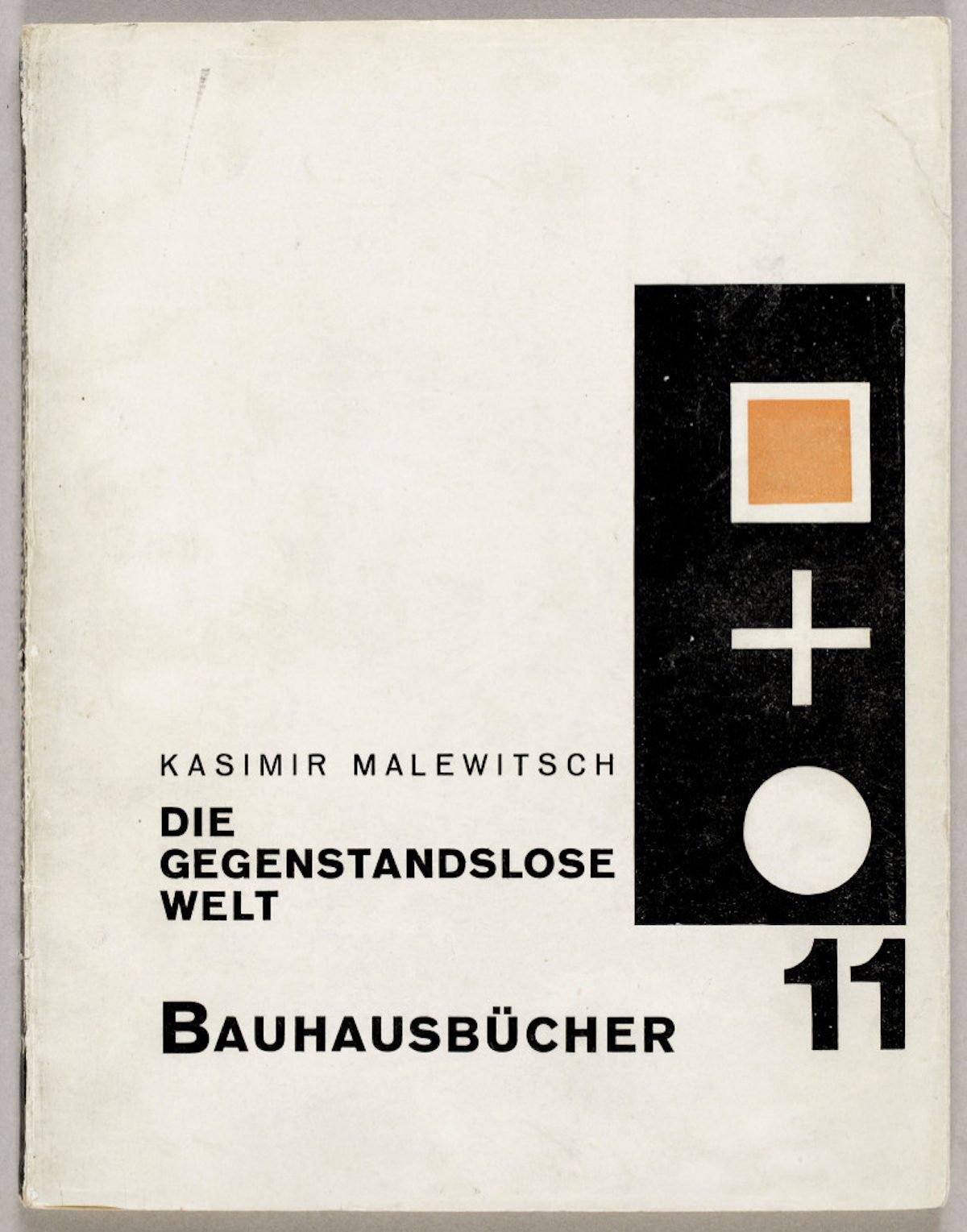

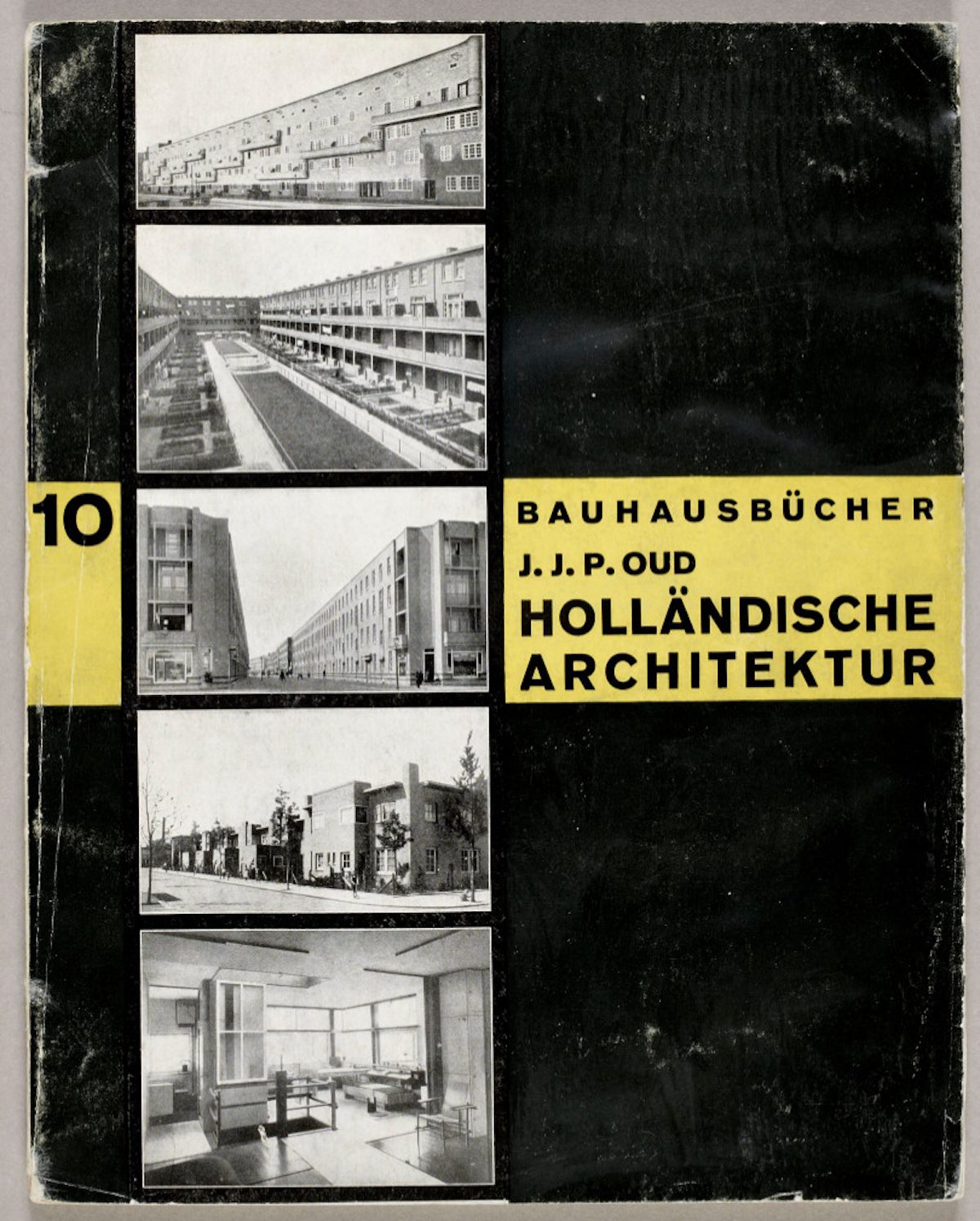

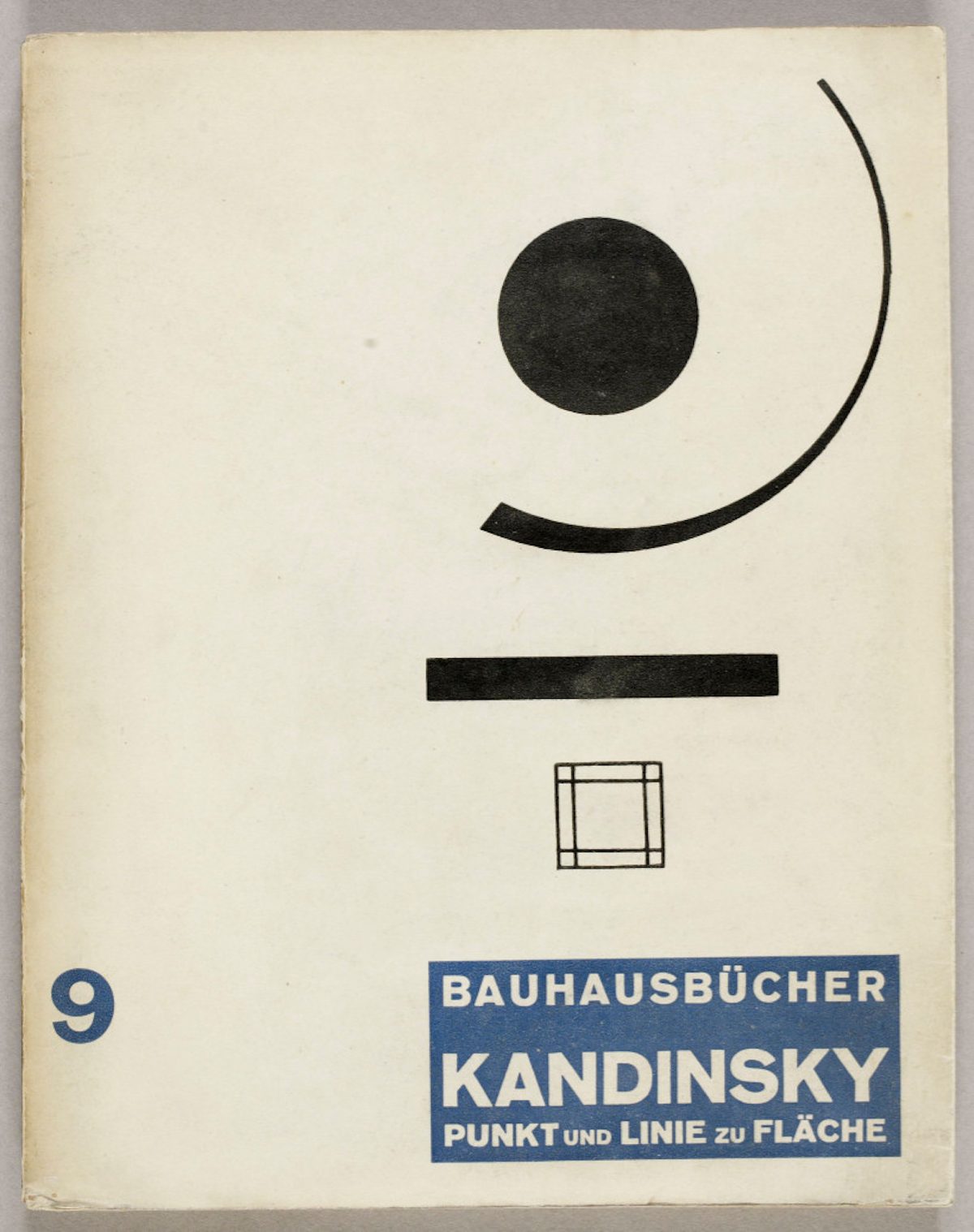

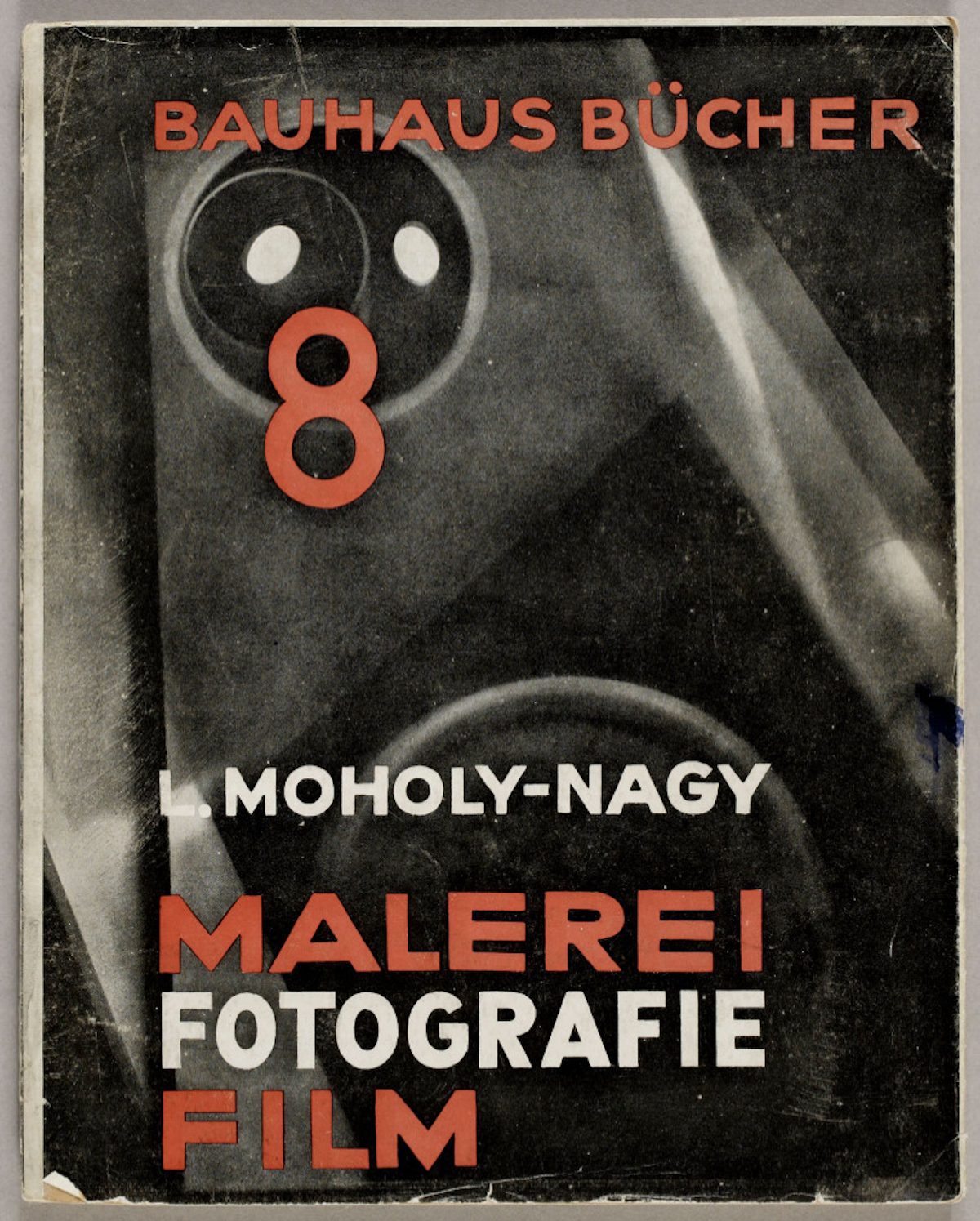

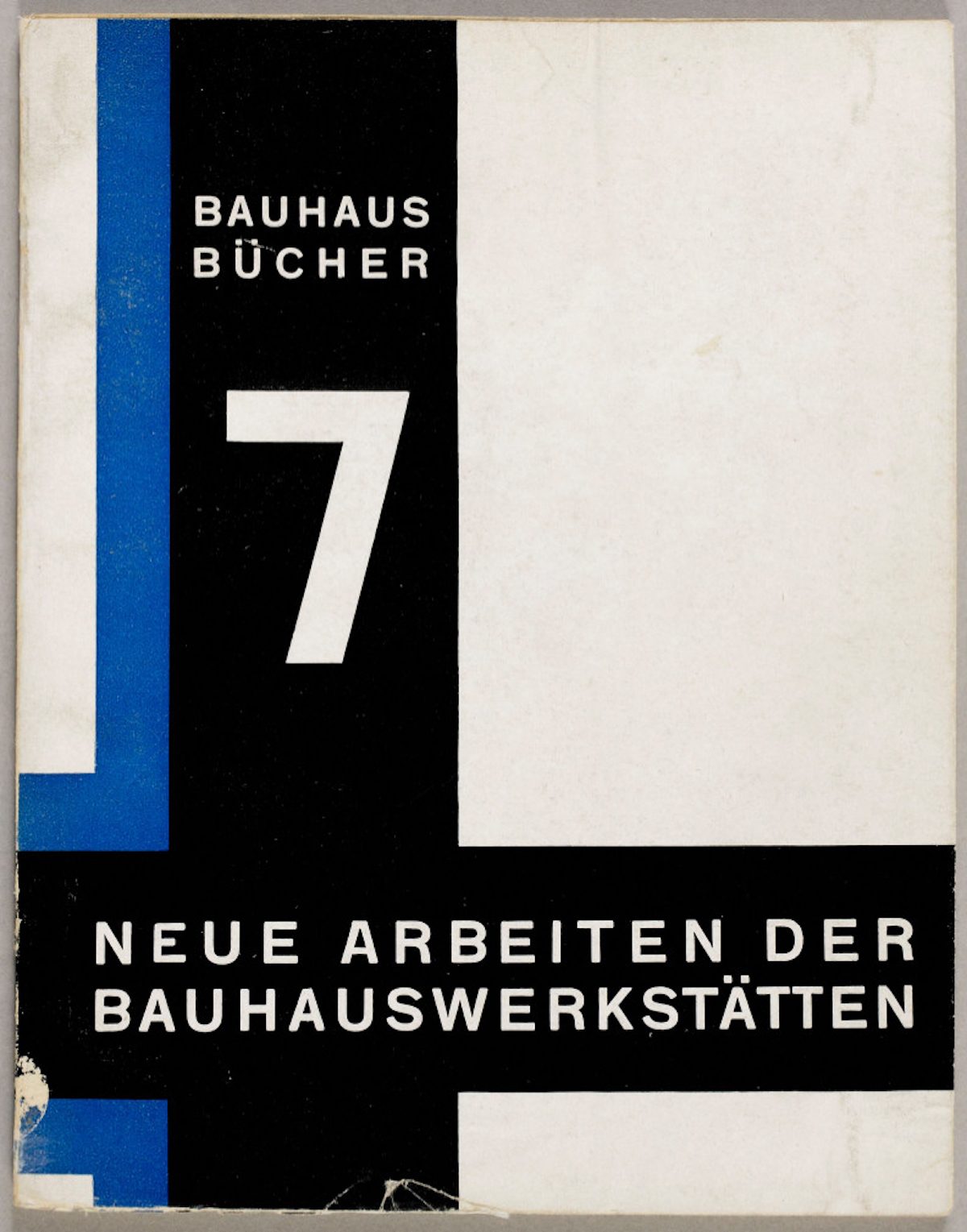

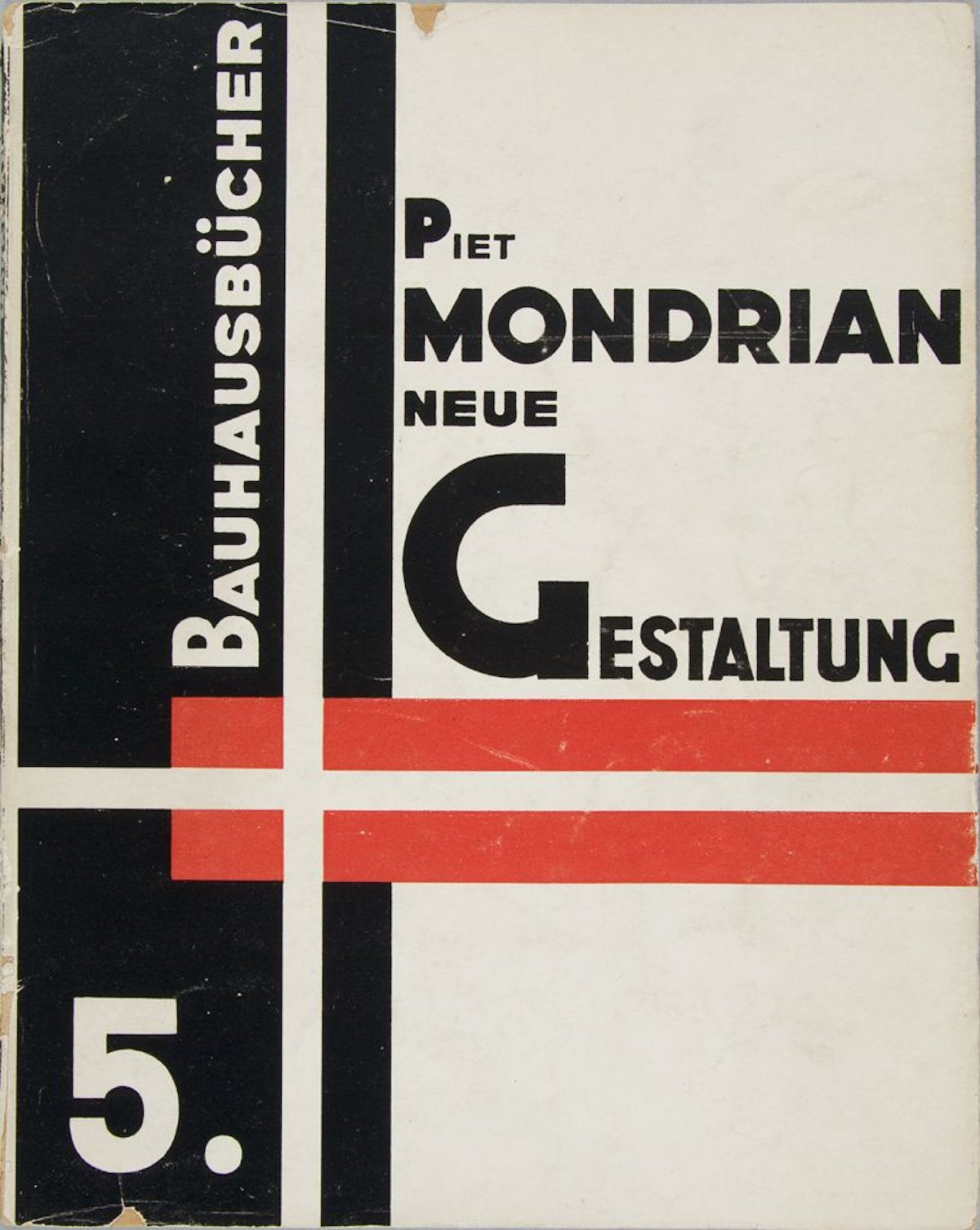

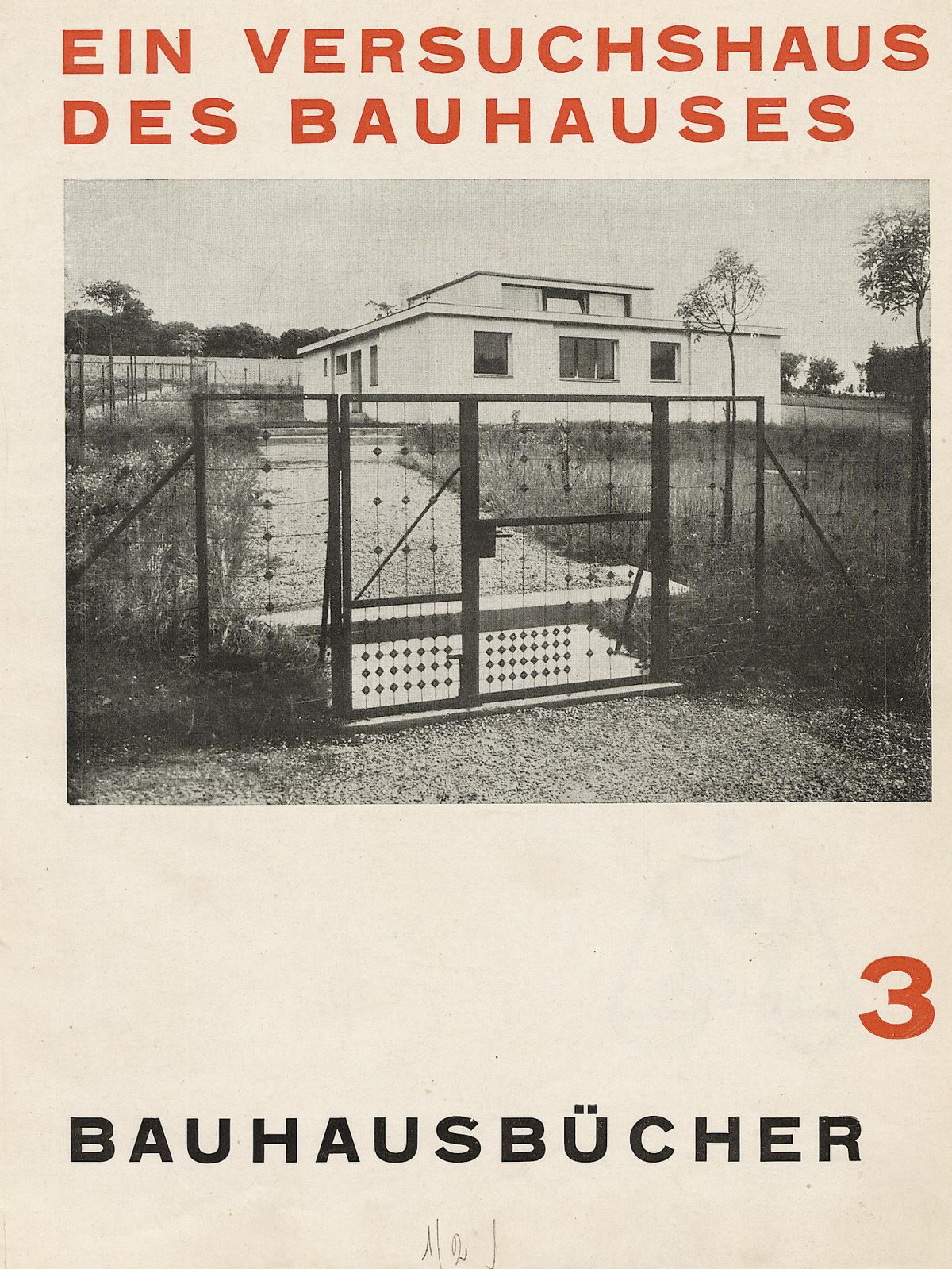

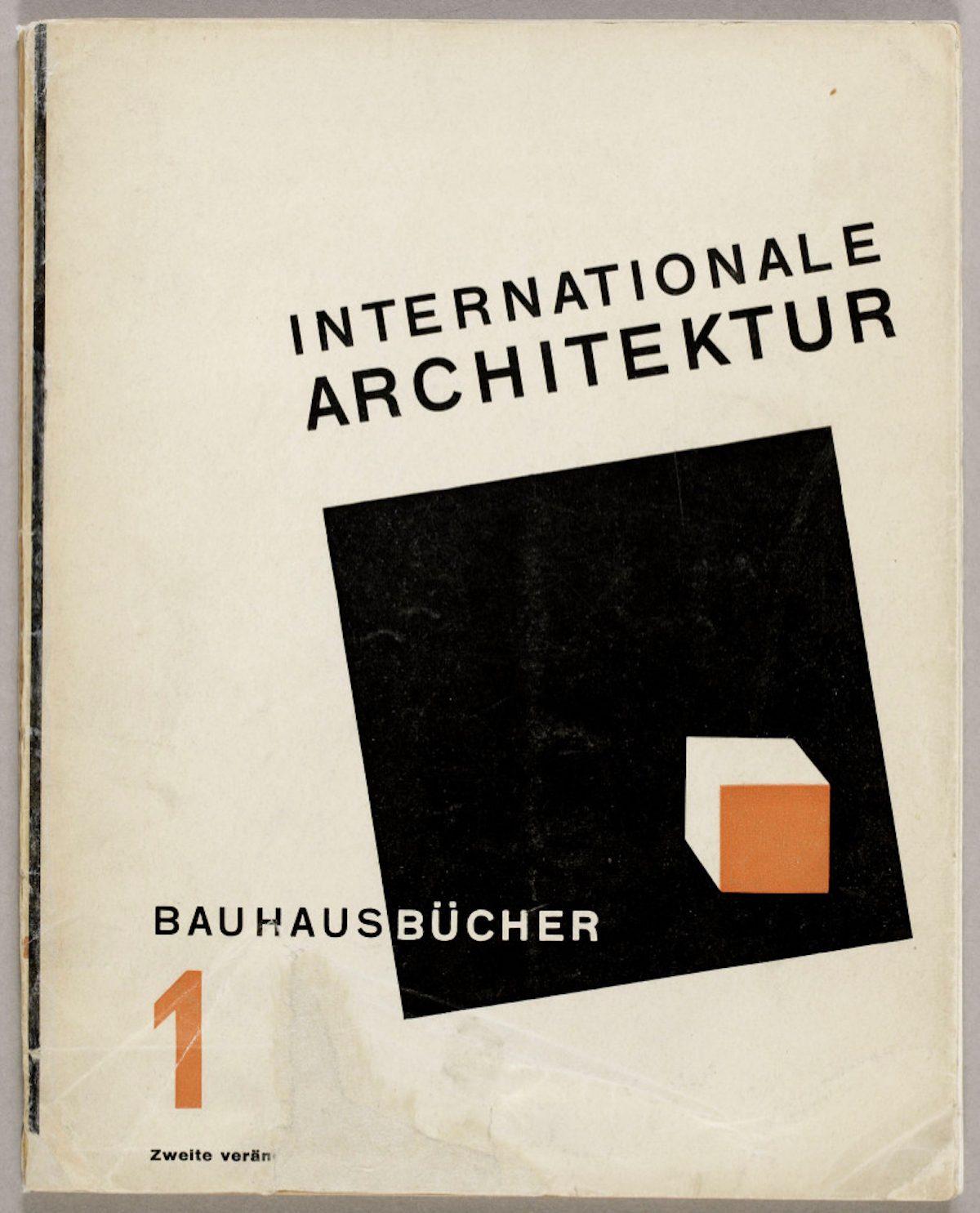

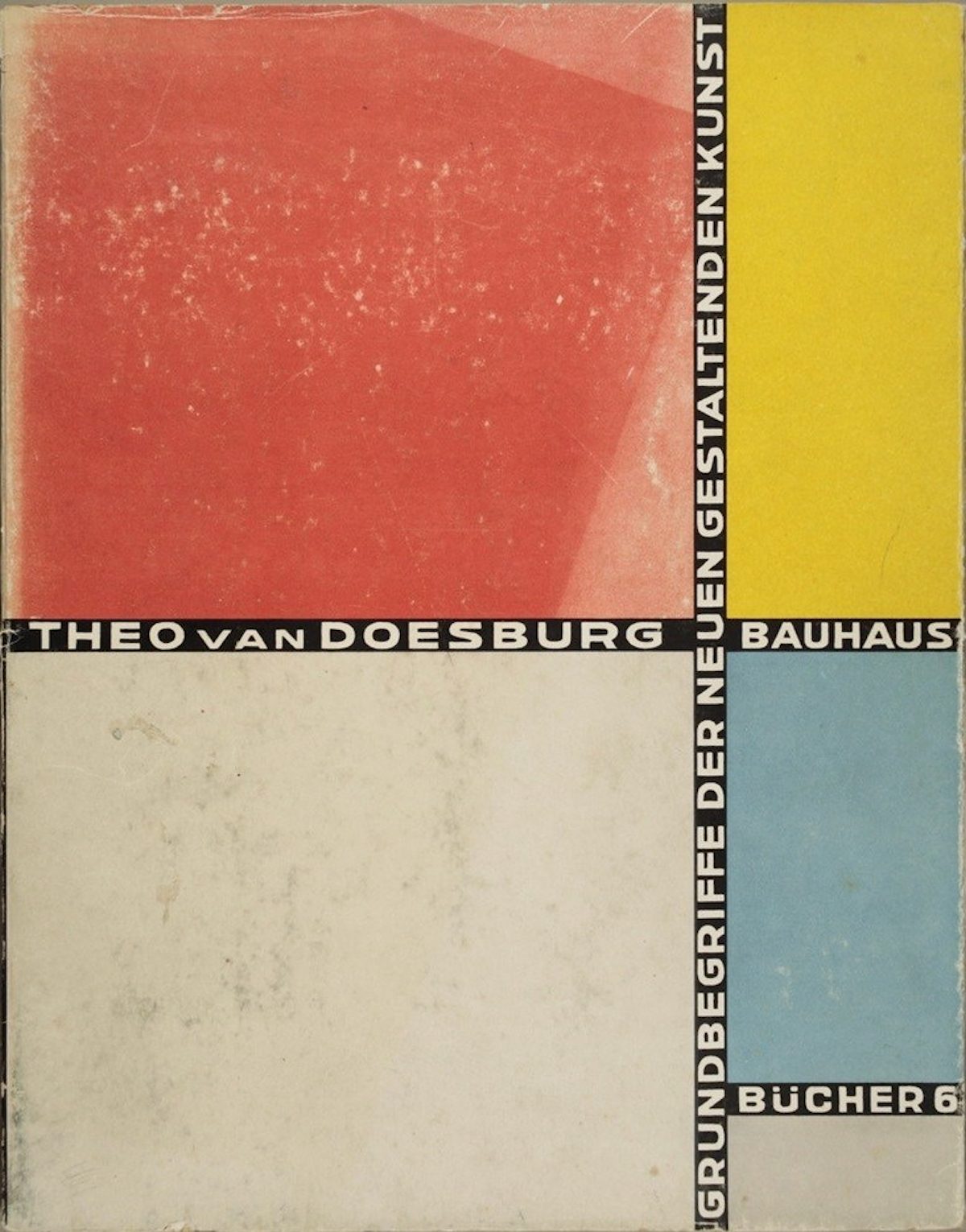

In order to make the sustained case for the “new system,” Gropius and László Moholy-Nagy began a book series in 1923 when the school acquired its own publishing house. Publishing was a PR move, “a strategy against the growing political pressure felt in Weimar,” says artist Ute Brüning. Gropius felt the need to “counter criticism and attacks” and “improve the school’s image and support its uncertain position.” Out of a planned program of 30 books, they printed 14, between 1925 and 1930, in addition to the Bauhaus journal, printed until 1931. Each Bauhaus book was totally unique, a monograph showcasing the theories and works of individual artists and instructors at the school.

The school achieved a surprising level of “aesthetic diversity,” says Rinkenburger. It is a characteristic that “is often lost today,” he argues, “largely due to the global hegemony of graphics software.” The Nazis effectively put an end to Bauhaus in 1932, but revisiting these beautifully designed artifacts can show a way out of contemporary copy-and-paste digital design, through the principles of a movement that looked back, forward, and in every other direction for inspiration. See the full series of Bauhaus Books at the Bauhaus Bookshelf.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.