“If ‘technology’ is that which is invented after we are born, and ‘stuff’ is that which has always been around, for those born now, computers, the internet and mobile phones are just stuff – in fact, it would be impossible for recent generations to imagine a world without these things. This was the world that the typewriter lived in”

– Barrie Tullett

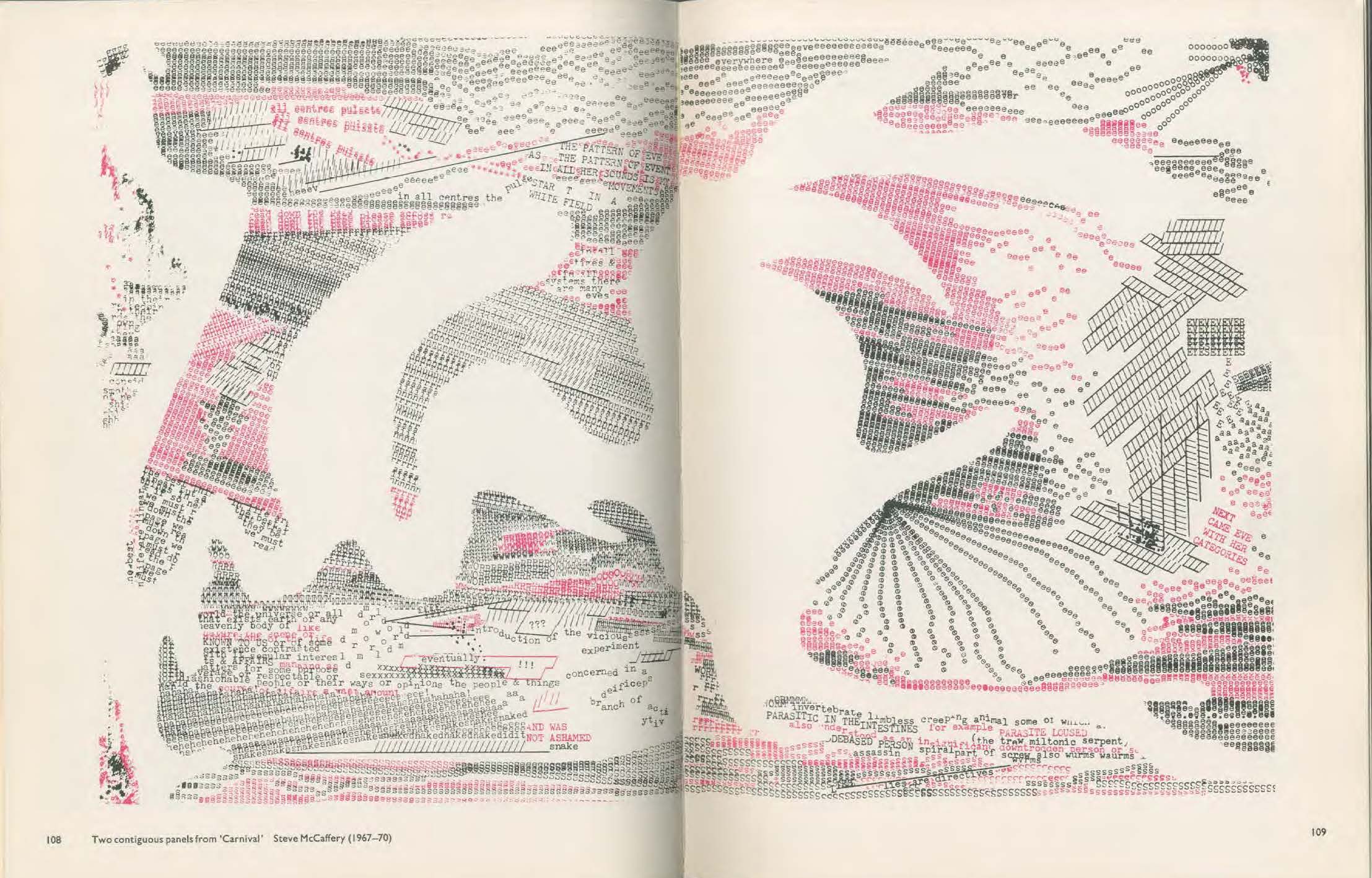

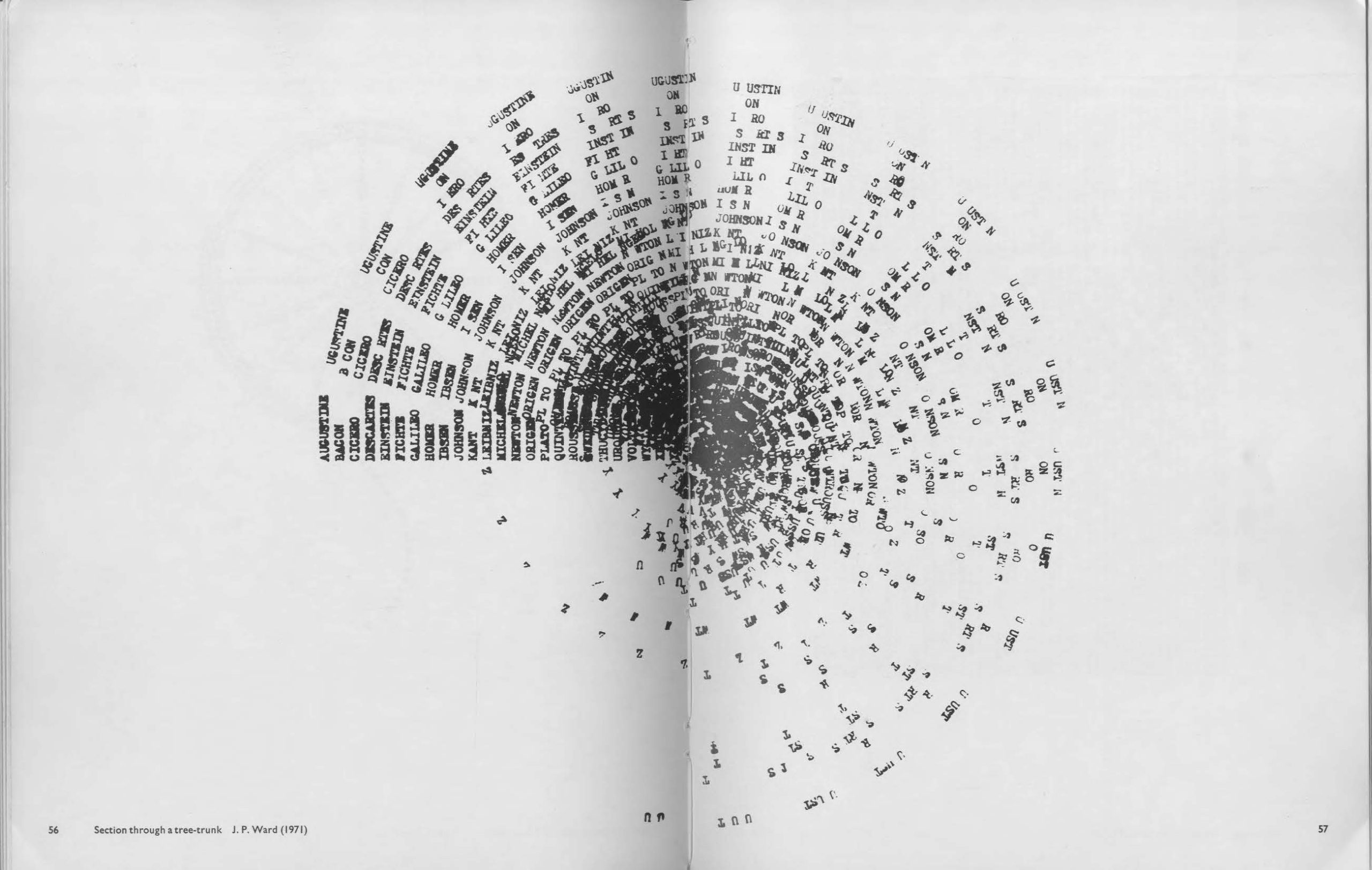

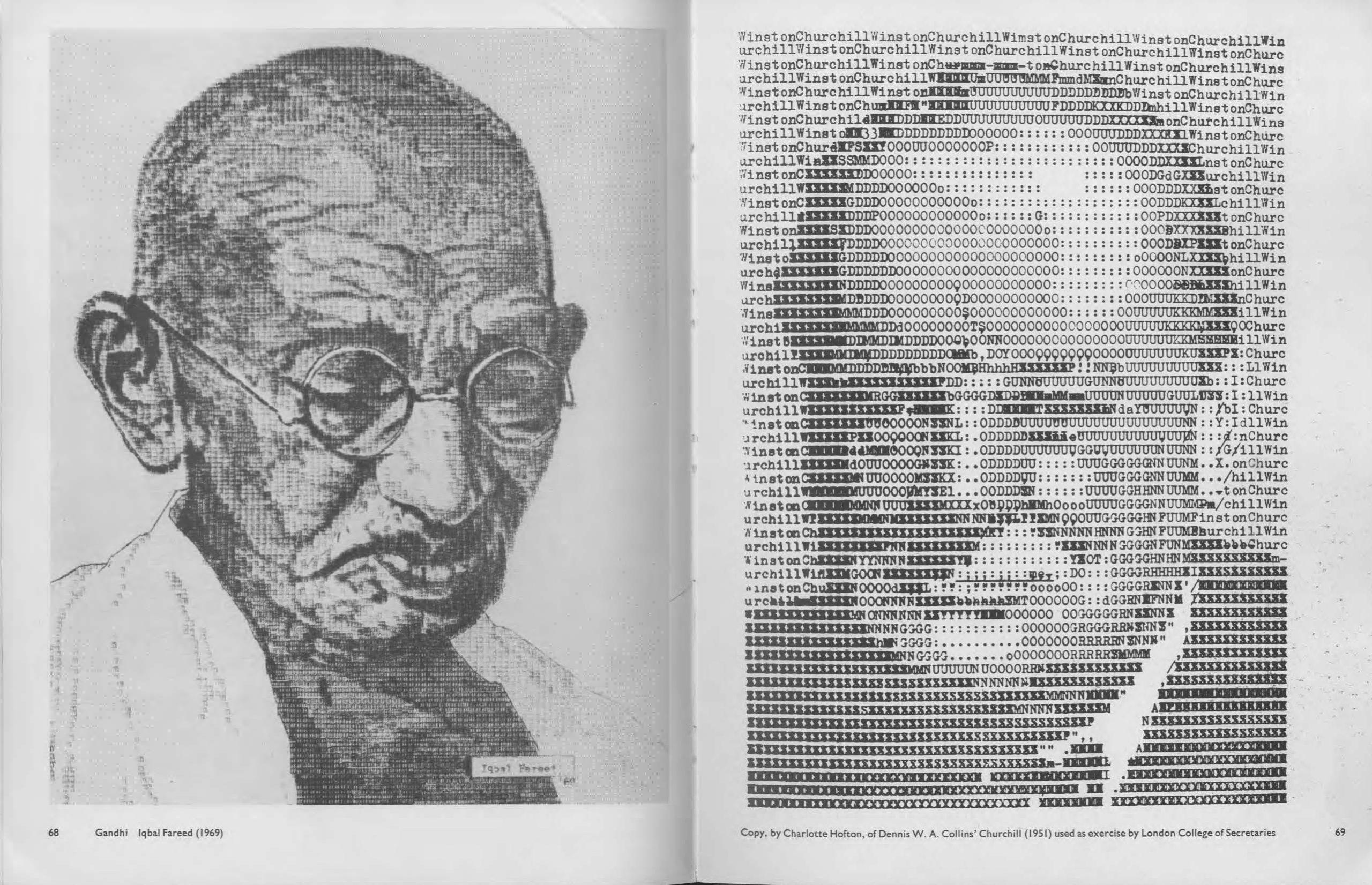

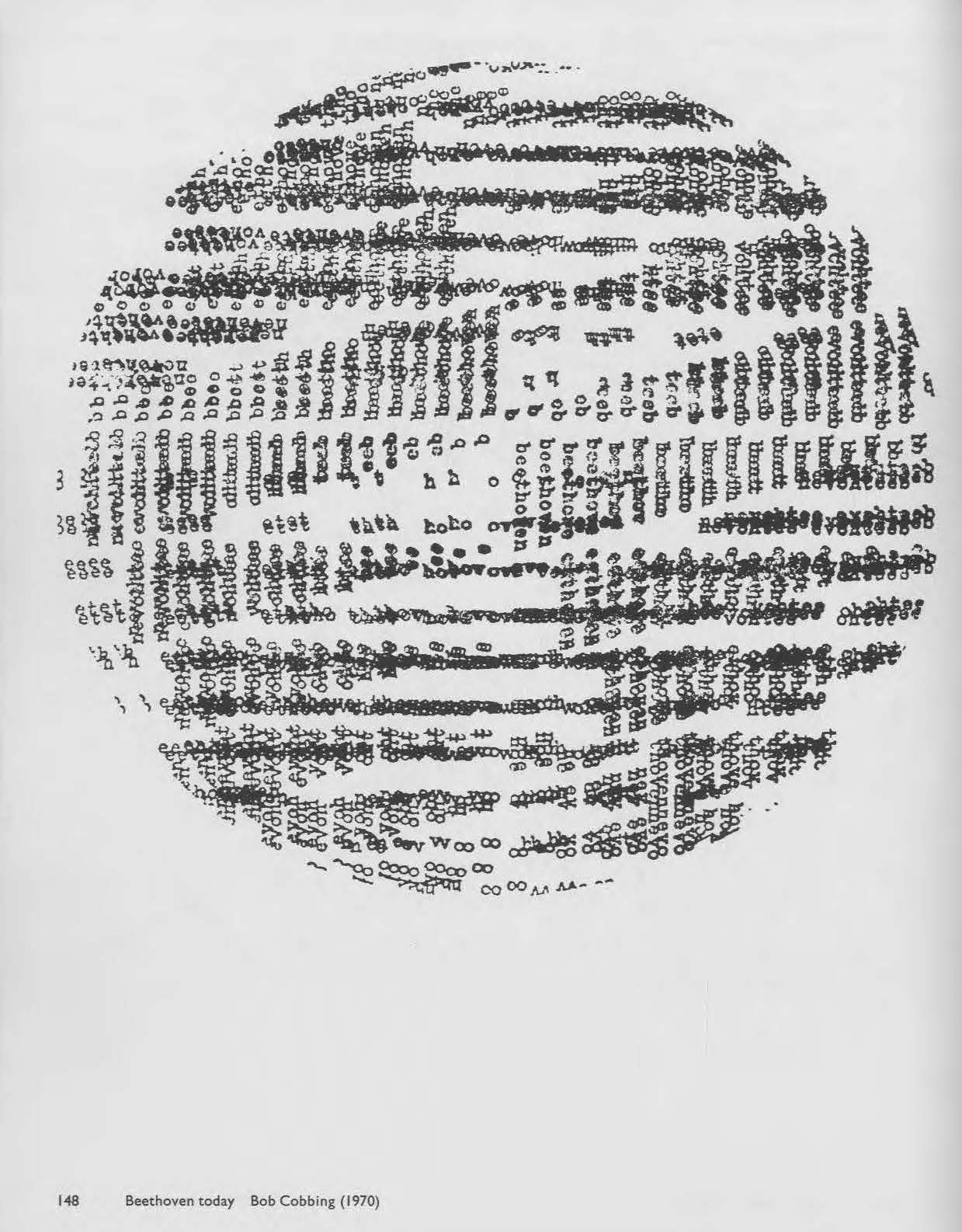

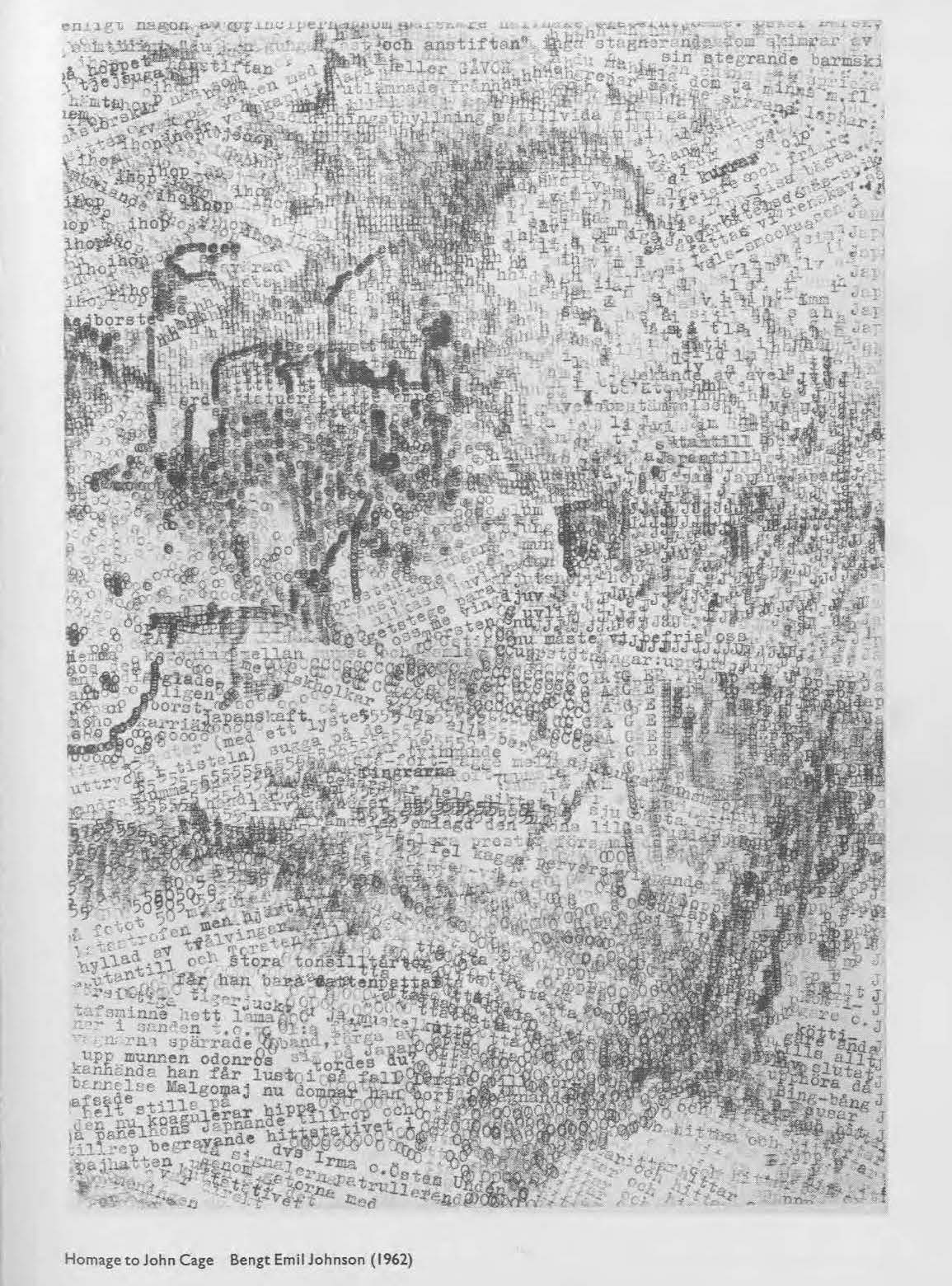

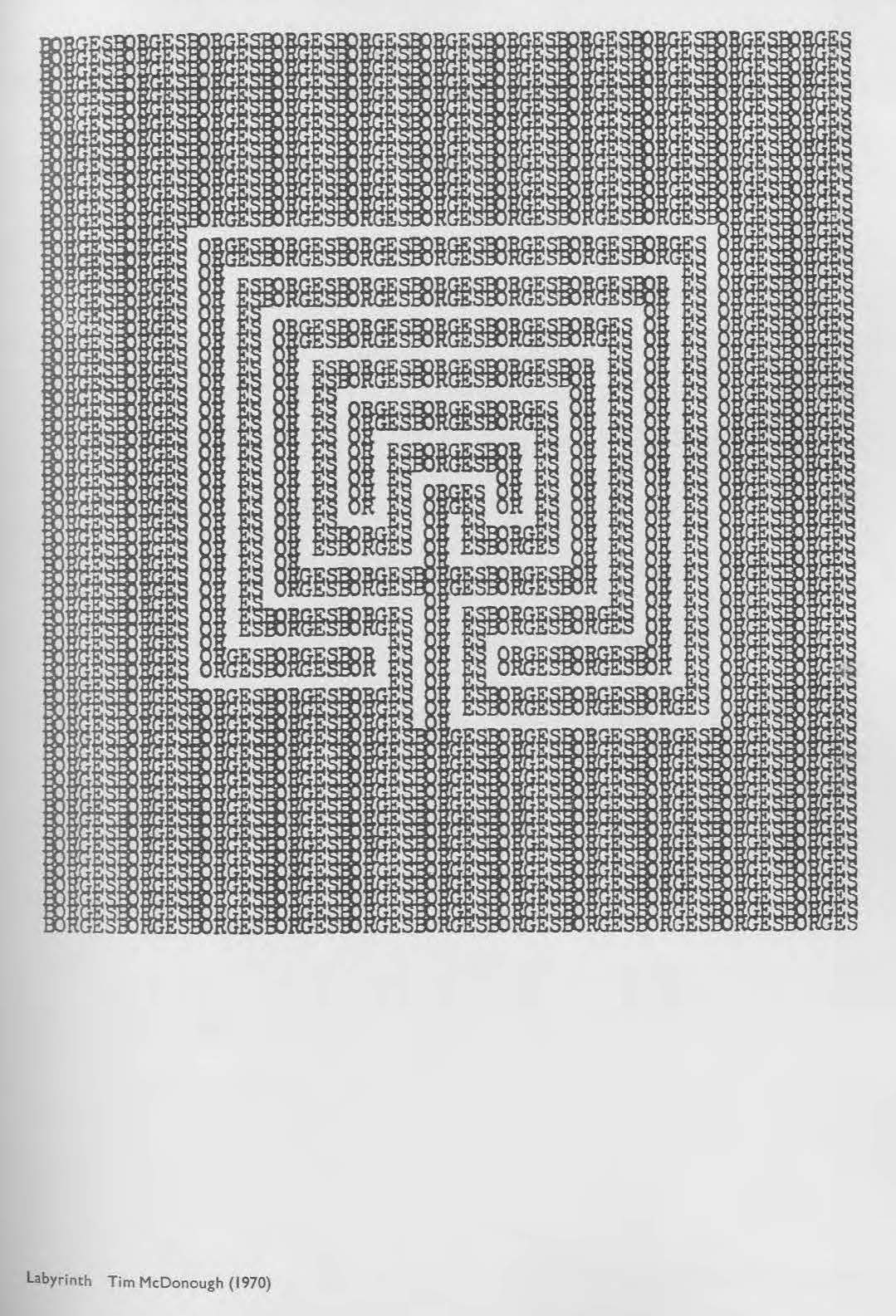

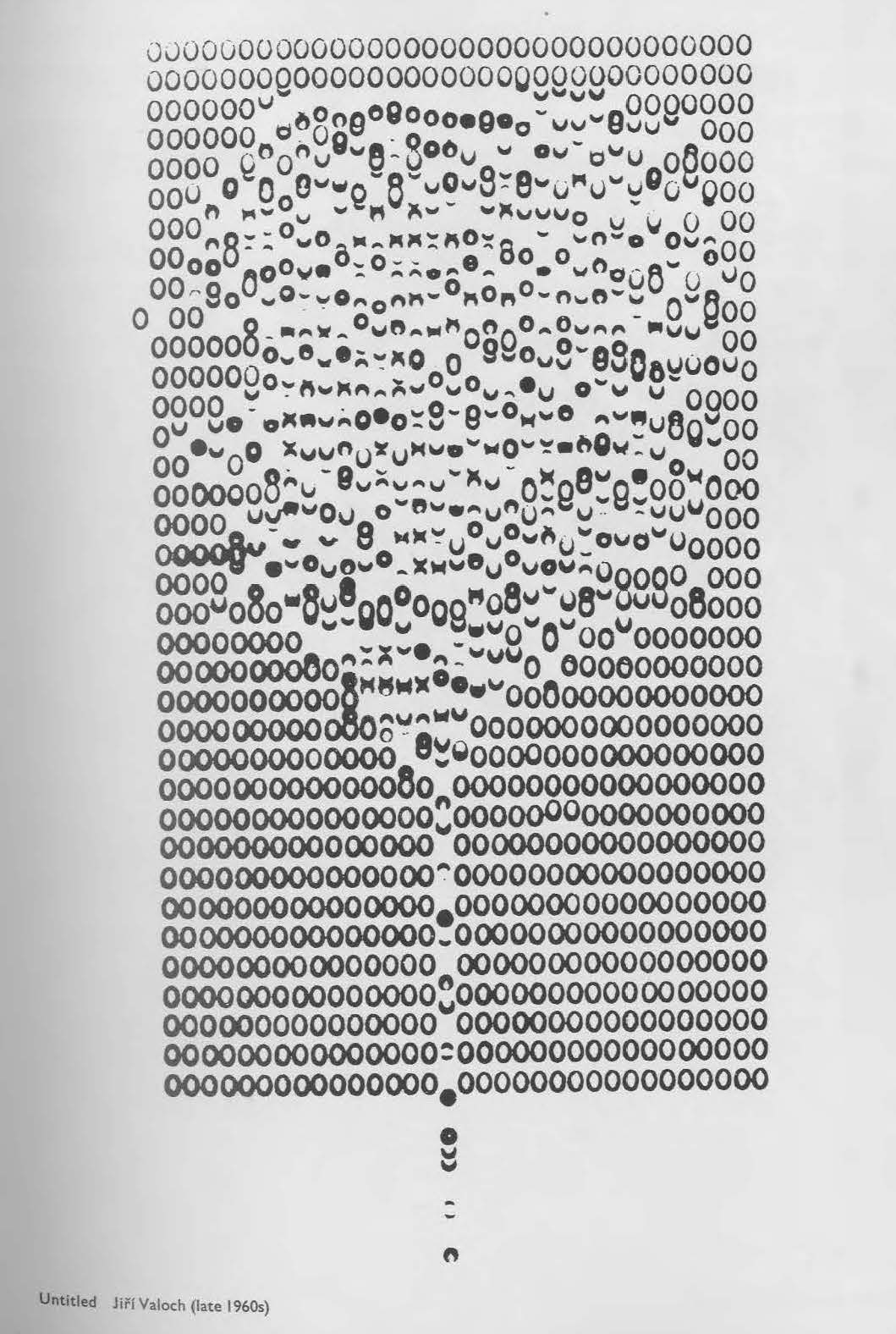

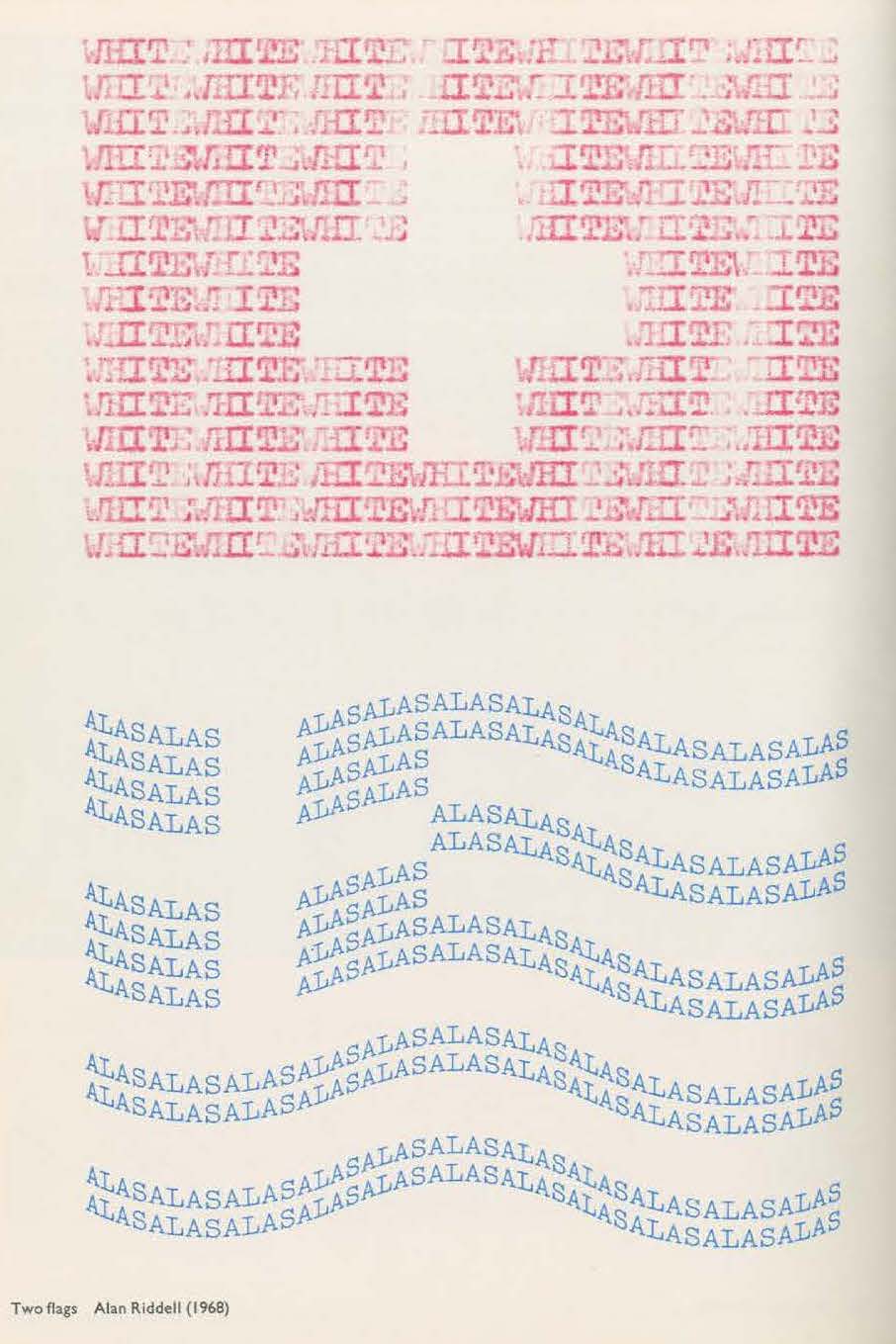

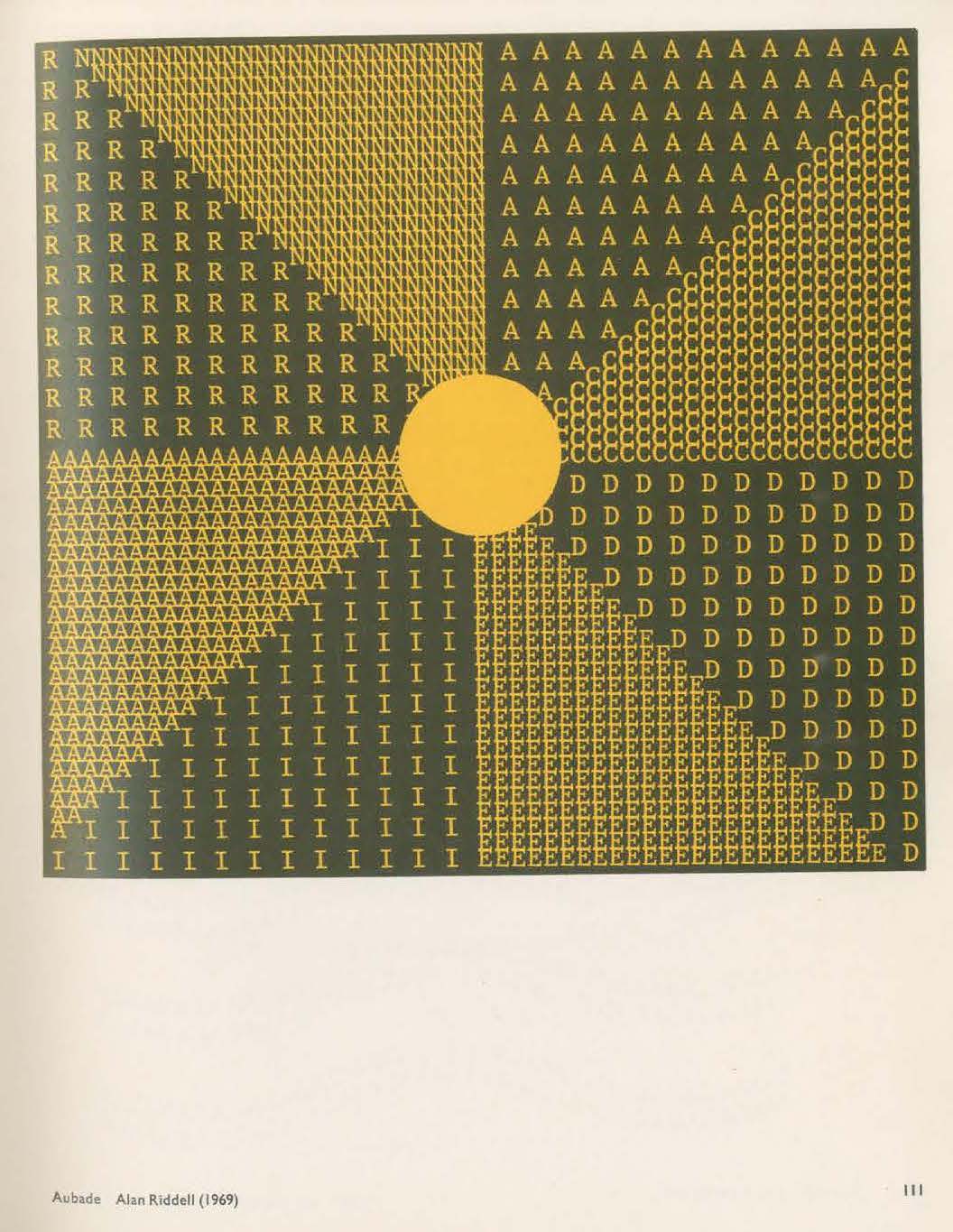

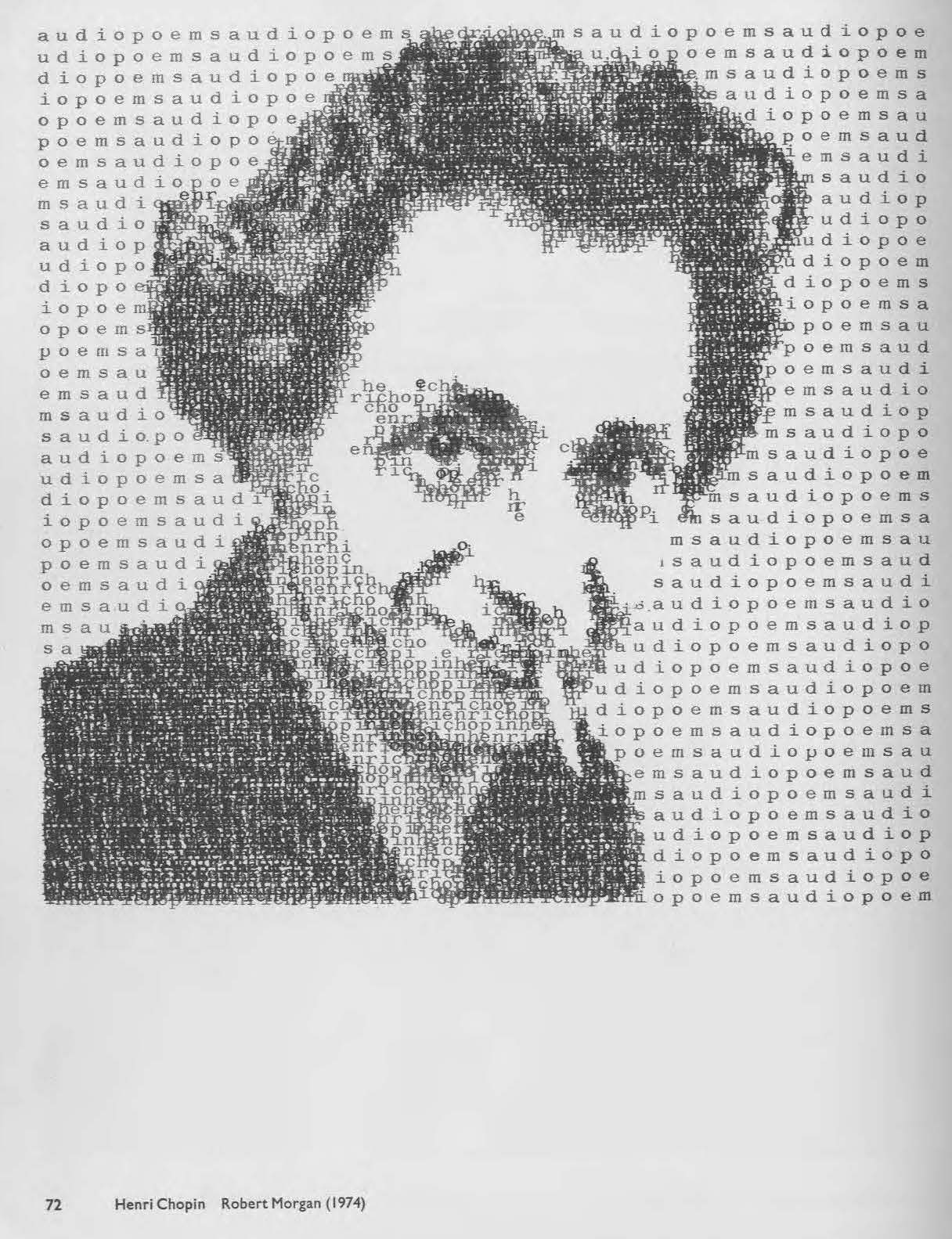

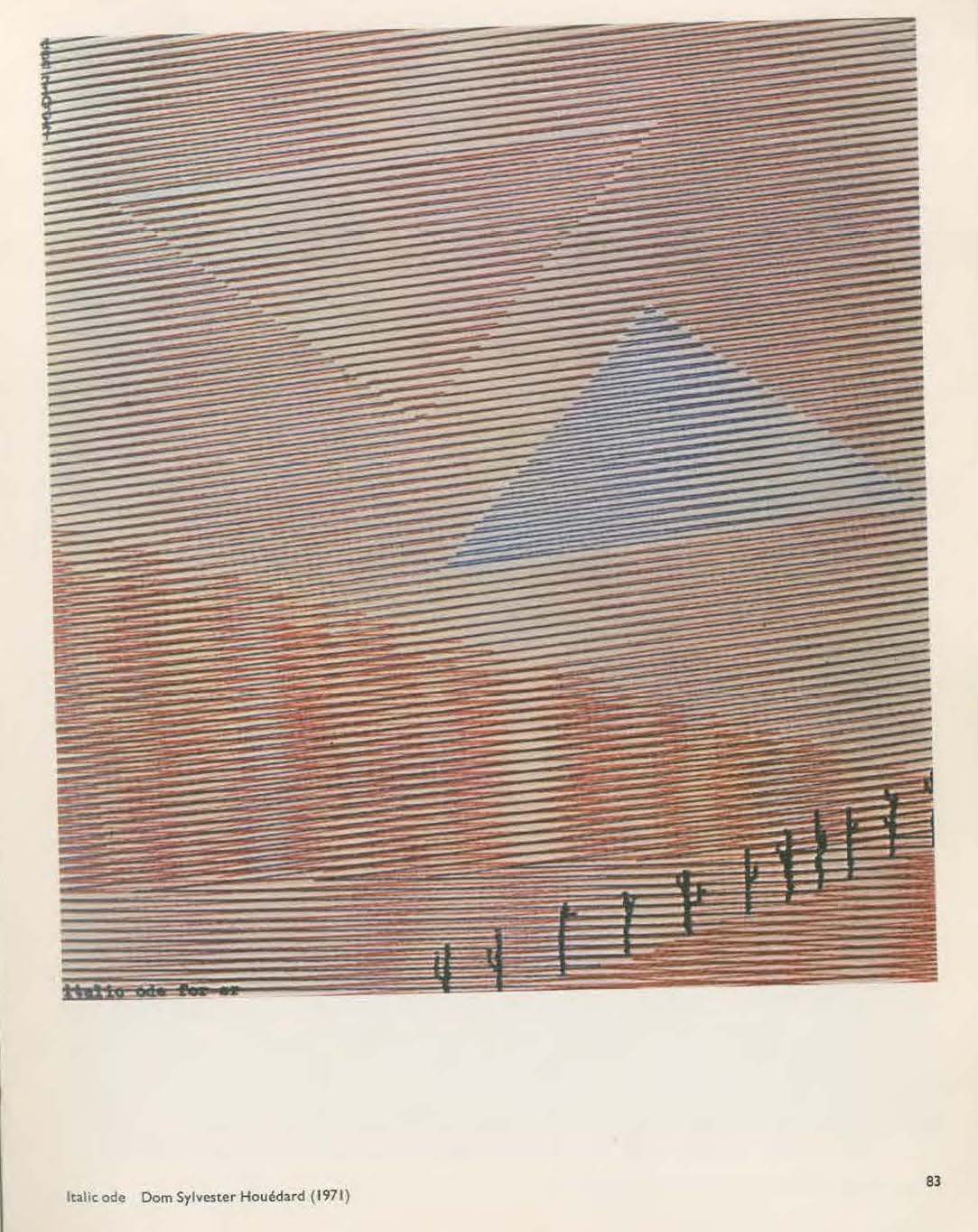

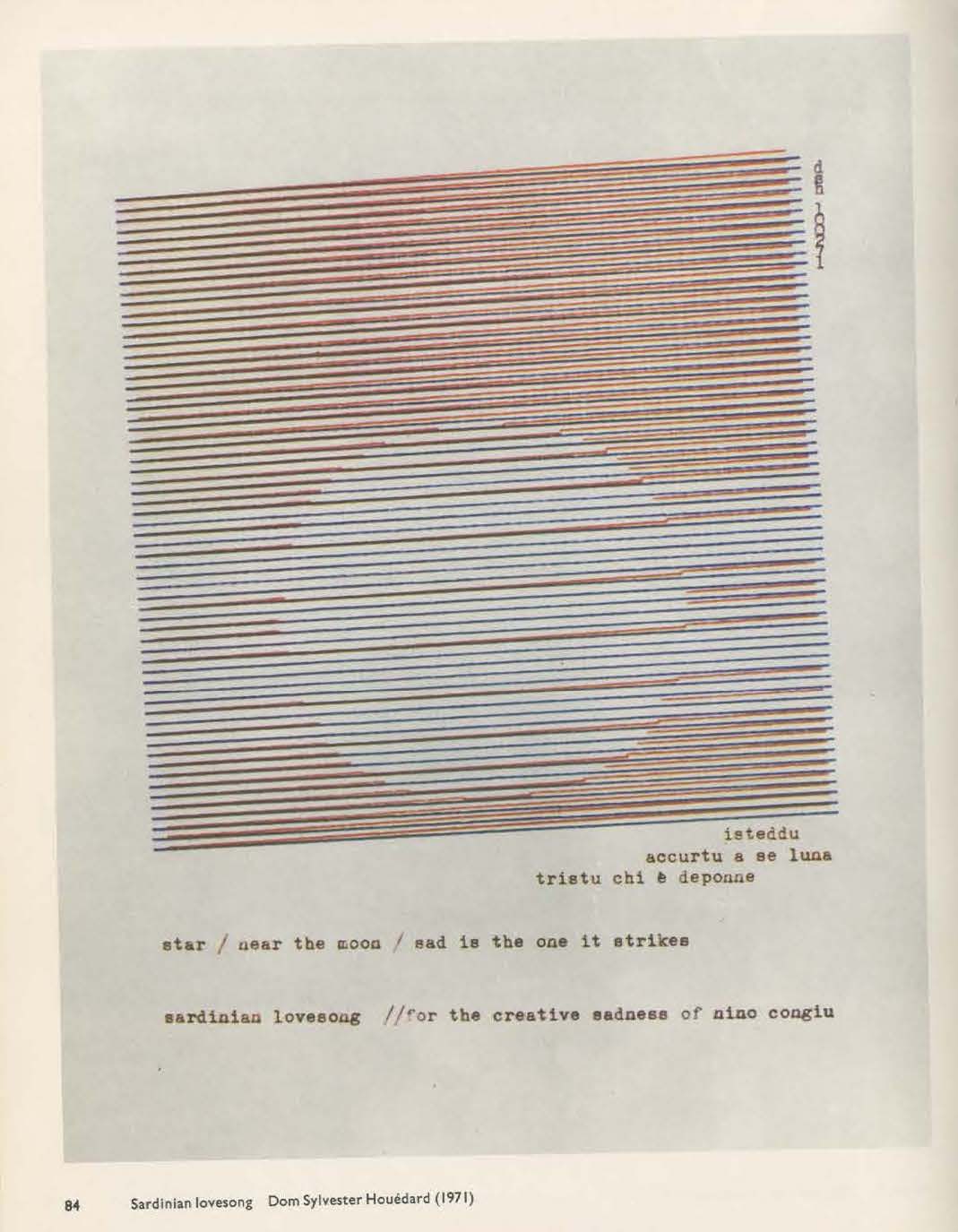

Alan Riddell’s Typewriter Art (1975) is a compilation of typographical artwork made between the 1890s and the 1970s – “119 works by 65 practitioners from 18 countries.” In a essay, Riddell links the medium to the concrete poetry movement, a form of visual poetry in which the typographical effect is more important in conveying meaning than verbal significance.

Riddell reminds us that the typewriter was once at technology’s leading edge , using a 1878 quotation from Mark Twain that reviews the “new-fangled writing machine”:

“It will print faster than I can write. One may lean back in his chair and work it. It piles an awful stack of words on one page. It don’t muss things or scatter ink blots around. Of course it saves paper.”

As Barrie Tullett notes the introduction to his excellent book Typewriter Art: A Modern Anthology:

The first commercial machine, the Hansen Writing Ball, was made available to the public in 1870; however, it was not until 1874 that the first truly successful machine appeared. Based on a design by Christopher Latham Sholes and Carlos Glidden, it was produced by the American firearms and sewing-machine manufacturer Remington and sat on the same base as their lock-stitch sewing machine.

The typewriter quickly became a fundamental part of our cultural, social, commercial and industrial world. It was instrumental to the emancipation of women, opening up a whole new field for female employment; it placed the means of communication in the hands of the people, uncensored by political doctrine or regime; it allowed writers to write as quickly as they thought. These machines created a clean, universal format, allowing for the immediate, and modern, presentation and dissemination of thought in a way that handwriting never could.

It was a revolution.

Via: monoskop

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.