“We cannot maintain that in everything woman is man’s equal, yet in many things her patience, perseverance, and method make her his superior.”

– Williamina Fleming in A Field for Woman’s Work in Astronomy, published in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics

Williamina Fleming (15 May 1857 – 21 May 1911) has one of those stories that needs retelling. At age 21, Fleming, one of nine children whose father had died when she was seven, emigrated to the US from Dundee, Scotland, with her husband, James Orr Fleming, a 36-year-old widower. He abandoned is pregnant wife in Boston. She soon took a job as a live-in maid at the home of Professor Edward Charles Pickering, director of the Harvard College Observatory. And in 1988, she discovered the Horsehead Nebula in Orion. She also spotted 10 novae, 59 gaseous nebulae, more than 300 variable stars, and recognised the existence of hot, Earth-sized stars later dubbed white dwarfs. She became the first American woman elected to honorary membership in England’s Royal Astronomical Society. So what happen in between to turn a singe mother and maid into a leading scientist?

![Williamina P. Fleming, photographic portrait, ca. 1890]](https://flashbak.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/22Williamina-P.-Fleming-photographic-portrait-ca.-1890.jpg)

Williamina P. Fleming, photographic portrait, ca. 1890

How Fleming became a revered astronomer was down to chance, opportunity and talent. Around 1875, the Harvard College Observatory (HCO) began admitting women as staff. Before then, women, like Eliza Quincy, daughter of founder Josiah Quincy, were only given volunteer status as observers, though several women had applied to work as student assistants.

When in 1876, Pickering, a supporter of female suffrage, became the Observatory’s 4th director, he hired women ‘computers’, paying 25-30 cents an hour for work 6 days a week – around half what a man earned for an equivalent job. Fleming noticed the discrepancy, of course, writing in her diary:

I am immediately told that I receive an excellent salary as women’s salaries stand. Does he ever think that I have a home to keep and a family to take care of as well as the men?…. And this is considered an enlightened age!

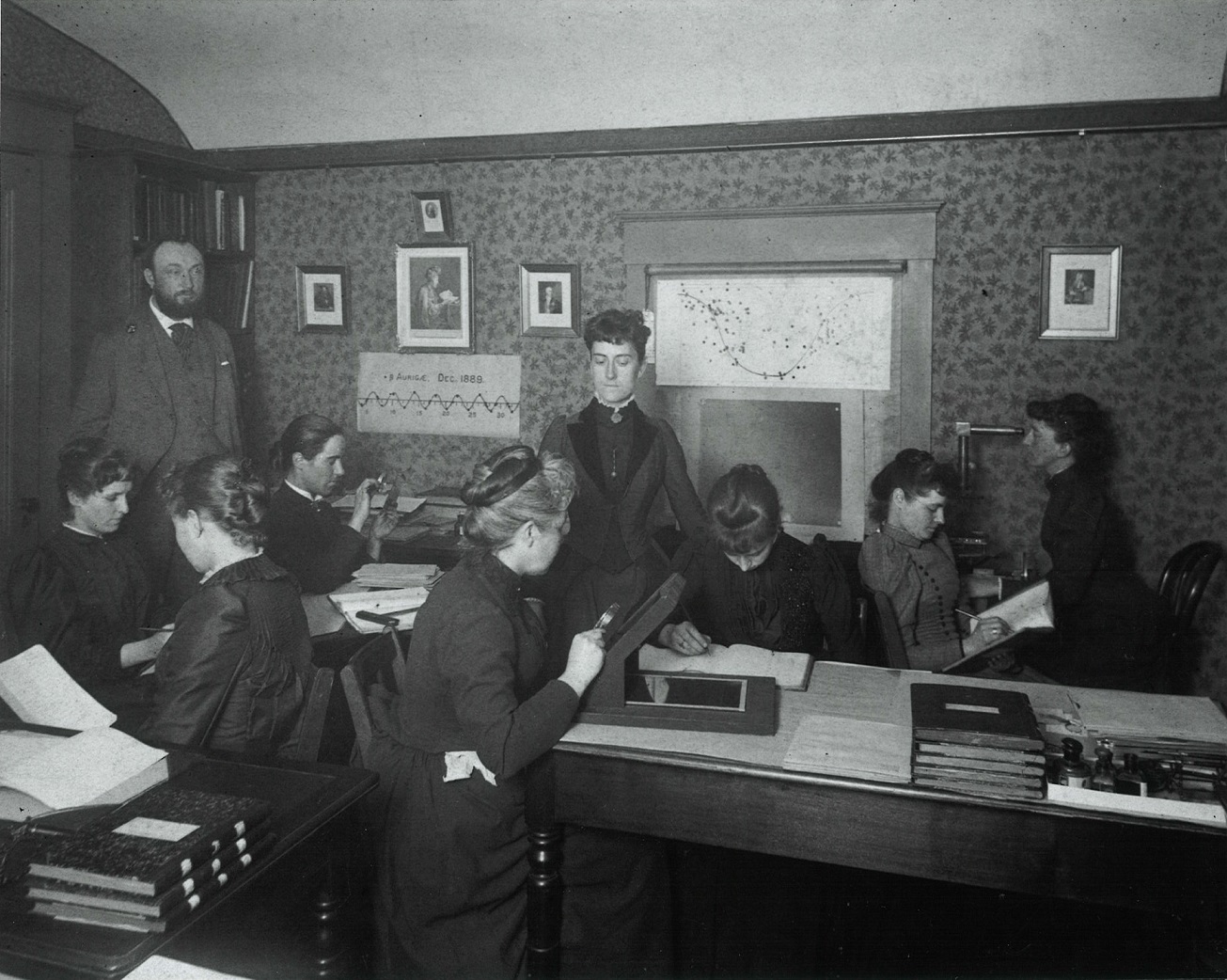

The women become known as Harvard Computers, which gave them the aura of being not entirely human, although their nickname, Pickering’s Harem, ranks them according only to their sex. So Harvard Computers it is, then. (The word computer originally referred to people who were so good at mathematics they “computed” for a living.)

A group of 80 women on the staff of the Harvard College Observatory were known as the “Harvard Computers.” The word computer originally referred to people who were so good at math they “computed” for a living.

In 1879, Pickering made arguably his best appointment, hiring Fleming to care for the observatory house, where the directors traditionally live. Pickering’s wife, Elizabeth, spotted that Williamina, a trained teacher (at 14, she had become a student teacher to help support her widowed mother and eight siblings), had talent. And in 1881, Pickering hired her to work at the observatory. She worked hard, mainly analyzing photographic plates. She wrote in her diary:

From day to day my duties at the Observatory are so nearly alike that there will be little to describe outside ordinary routine work of measurement, examination of photographs, and of work involved in the reduction of these observations.

…

Looking after the numerous pieces of routine work which have to be kept progressing, searching for confirmation of objects discovered elsewhere, attending to scientific correspondence, getting material in form for publication, etc, has consumed so much of my time during the past four years that little is left for the particular investigations in which I am especially interested.

She did publish the results of her own investigations, though, and was among the few women who participated in research conferences. In 1898, she received an ovation from a national gathering of astronomers. And she was hardly ungrateful for her job, naming her son Edward Charles Pickering Fleming. But while men got to take photos of the night sky in North America, Peru, South Africa, New Zealand and Chile, sending their photographic pates back to Harvard, women were given the less glamorous jobs. As Alan Hishfeld writes in Harvard Magazine:

By night, Harvard astronomers photographed stars and nebulae; by day, specially trained office workers—“computers”—inspected and analyzed the images. For that task, Pickering hired women, believing them better suited to such repetitive drudgery, and he placed Fleming in charge. (Legend says that he took his own advice after angrily telling a male employee that his housemaid could do a better job.)

Fleming was soon charged with the management of the women computers. When in 1882, astronomer Henry Draper died, his wealthy widow, Mary Anna Draper, kickstarted the Henry Draper Memorial to fund the HCO’s research. The HCO duly began work on the first Henry Draper Catalog, a long-term project to obtain the optical spectra of as many stars as possible and to index and classify stars by spectra. (Augmenting the observatory camera was a spectrograph that projected onto a single photographic frame the spectra of dozens of stars.) The burgeoning collection of spectrum plates became the root of much of Fleming’s scientific work. Fleming was placed in charge of the catalog project, which published astronomical findings in the Draper Catalog of Stellar Spectra.

“In the Astrophotographic building of the Observatory, 12 women, including myself, are engaged in the care of the photographs…. From day to day my duties at the Observatory are so nearly alike that there will be little to describe outside ordinary routine work of measurement, examination of photographs, and of work involved in the reduction of these observations.” – Williamina Fleming

“[Women on-board ship, ca. 1900].” Harvard University Archives / UAV 630.271 (173). Harvard Libraries, olvwork431825

A group of women, most or all computers from the Observatory, on board the C.S. Minia, a cable repair ship. On the early end for possible dates of this picture, Mabel Gill (holding Fleming’s hand) was hired in 1892 (assuming she had been hired at this point).

The latest Harvard College Observatory images contained photographed spectra of stars that extended into the ultraviolet range, which allowed much more accurate classifications than recording spectra by hand through an instrument at night. Fleming devised a system for classifying stars according to the relative amount of hydrogen observed in their spectra, known as the Pickering-Fleming system. Stars showing hydrogen as the most abundant element were classified A; those of hydrogen as the second-most abundant element, B; and so on.

Later, her colleague Annie Jump Cannon, an astronomer, suffragist and a member of the National Women’s Party, reordered the classification system based upon the surface temperature of stars, resulting in the Harvard system for classifying stars that is still in use today.

As a result of years of work by their female computer team, the HCO published the first Henry Draper Catalog in 1890. It listed the position, brightness and spectral type of 10,351 stars. The majority of these classifications were done by Fleming, who also made it possible to go back and compare recorded plates, by organising thousands of photographs by telescope along with other identifying factors In 1898, she was appointed Curator of Astronomical Photographs at Harvard, the first woman to hold the position.

Annie Jump Cannon, an astronomer who co-invented a stellar classification system that is still in use today. (Harvard University Library) . c. 1922

Annie Jump Cannon was mostly deaf due to contracting scarlet fever after finishing college at Wellesley. She studied stellar spectra and upgraded Fleming’s stellar classification system. She lead a team of computers in publishing nine volumes of the Henry Draper Catalogue between 1918-1924. She also creates the Harvard Catalogue of Variable Stars and the star classification sequence OBAFGKM (known by its mnemonic device: Oh Be A Fine Girl, Kiss Me).

In 1899, Williamina Fleming was appointed as the first Curator of Astronomical Photographs, making her the first woman to hold an official title at the observatory, and at Harvard University at large. She held the post until she died in 1911.

And after the trailblazers, more women came to the fore.

In 1907, Pickering announced his intention of creating a standard Polar sequence of stellar brightness (magnitude). Henrietta Swan Leavitt, who was partially deaf like Cannon, was hired as the leading computer on the project. Leavitt searched for variable stars in the Magellanic Clouds. Her most common method was through superposition, placing one negative atop another that was taken at a later date. By the time of her death in 1921, she’d discovered around 2,400 variable stars. She also developed a method for measuring celestial distances through periodic-luminosity relations.

In 1914, Anna Draper died and wills an additional $150,000 to her Henry Draper Memorial fund. The fund still supports the Curator of Astronomical Photographs position today.

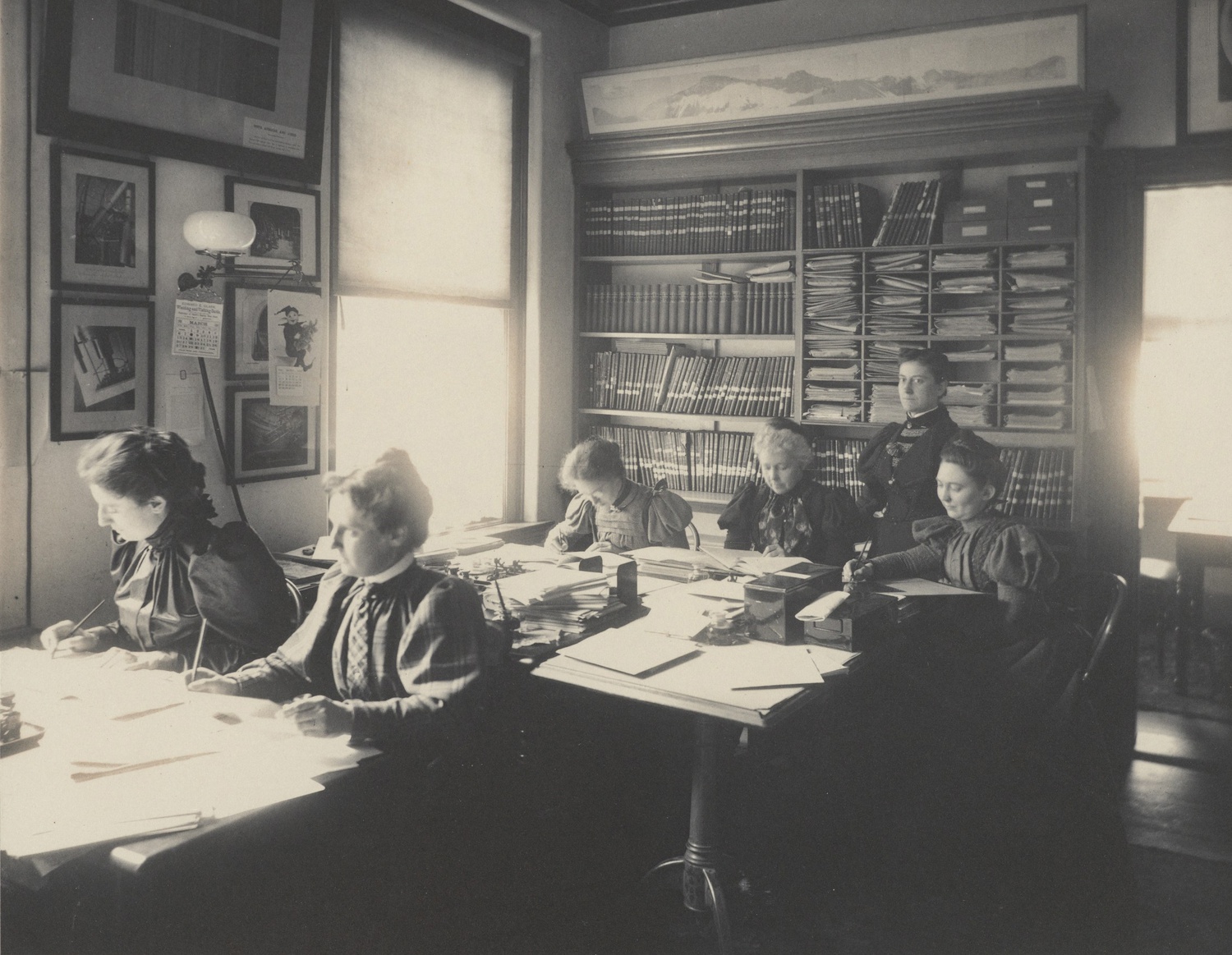

Observatory girls with Mrs. Draper, 1891

A revolution was underway.

In 1925, Cecelia Payne-Gaposchkin became the first person to earn a PhD in astronomy from Harvard, though, as a woman, her degree officially cames from Radcliffe. (Women were not admitted into Harvard until 1977, though they’d taken classes with the Harvard professors through Radcliffe for about a century.) The university created the degree especially for Payne-Gaposchkin. In her PhD research, Payne-Gaposchkin discovered that the atmosphere of the sun is made mostly of hydrogen, in contrast to the popular view that the sun had the same composition as the Earth. Astronomer Otto Struve calls her work “undoubtedly the most brilliant PhD thesis ever written in astronomy”,

In 1929, Edwin Hubble used Henrietta Leavitt’s work on celestial distance to discover that the universe is expanding. In 1932, Annie Cannon won the Ellen Richards research prize for women distinguished in science. She gives the reward money to the American Astronomical Society to establish the Annie Jump Cannon Prize for women astronomers, later won by the aforementioned Maury.

In 1938, Annie Cannon is finally recognized as the Curator of Astronomical Photographs by the Harvard Corporation. That same year she’s named the William Cranch Bond Astronomer at Harvard. She also becomes the first recipient of the Cecelia Payne Gaposchkin Award.

In 1t956-,Cecelia Payne-Gaposchkin became the first woman to be promoted to full professor within the Faculty of Arts and Sciences. She is later appointed the third chair of the Astronomy Department, making her the first woman to head a department at Harvard.

In the 1960s, Martha Hazen is appointed as the new Curator of Astronomical Photographs and began to organise the plates and data that had been largely neglected since the 1950s due to low staff and funding. In 1977, women students are finally admitted to Harvard University.

And in 1992, he last of the astronomical photographic plates are collected and the program is shut down. Advanced technology makes the collection of glass plate negatives obsolete.

Lead Image: “Computers” of the Harvard College Observatory often worked Monday through Saturday from 9 until 6, sometimes going home and working more hours into the evening. Williamina Fleming is standing. By Courtesy of the Harvard University Archives

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.