Robert Adamson (26 April 1821 – 14 January 1848) was a Scottish chemist and pioneer photographer who together with painter David Octavius Hill (20 May 1802 – 17 May 1870) in 1843 – just four years after the invention of photography had been announced – formed Hill & Adamson, a pioneering photographic studio at the foot of Calton Hill in Edinburgh, Scotland.

They produced hundreds of calotypes, mostly portraits, landscapes and social documentary. Because calotypes needed a lot of sunlight, many of their photographs were taken outdoors in their garden, which Hill designed to look like a convincing interior.

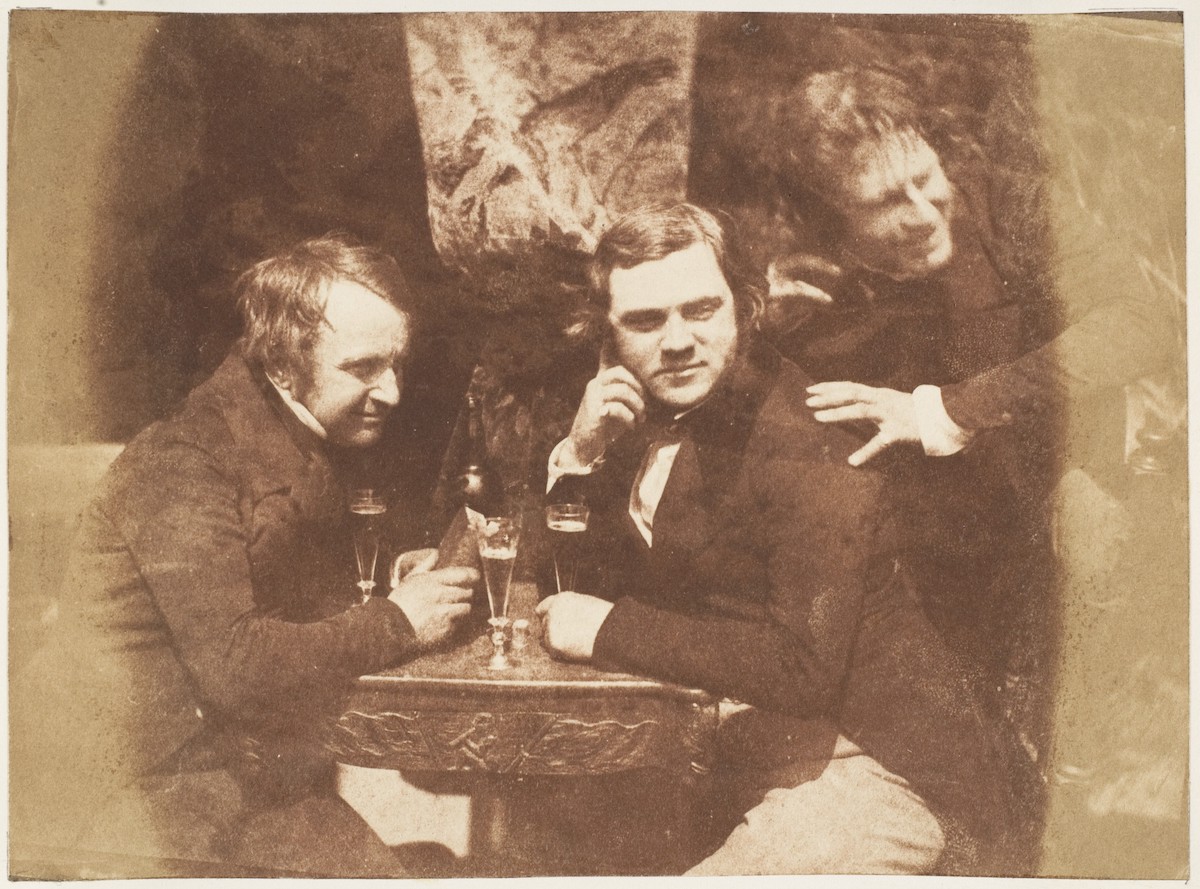

The drinkers. Edinburgh Ale James Ballentine, Dr. George Bell, D.O. Hill Photography Studio Hill and Adamson British, Scottish David Octavius Hill British, Scottish Robert Adamson British, Scottish 1843–47

Nowadays, it’s hard to avoid being photographed. If we’re not recording our every movement for social media – or filming someone else for our gratification and hits – we’re being observed. In 2012, Britain’s Association of Chief Police Officers (Acpo) said Britons are caught on camera 70 times a day on average. No figures have been issued since, but in 2015 The British Security Industry Association estimated there were between 4-5.9 million cameras in use in the county – and that was before doorbell cameras became popular.

There are an estimated 540 million CCTV cameras in China. Cameras watch citizens as they shop and dine. Cameras watch people as they leave home in the morning and return at night. There are stories of cameras watching workers inside toilet cubicles.

Much has changed, then, since when photography was new and taking a picture took minutes of exposure time and required a still-life subject or the human sitter to remain motionless.

The Daguerreotype, named after its French inventor, Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre (18 November 1787 – 10 July 1851), and the first publicly available photographic process, was expensive and slow. Something new was required.

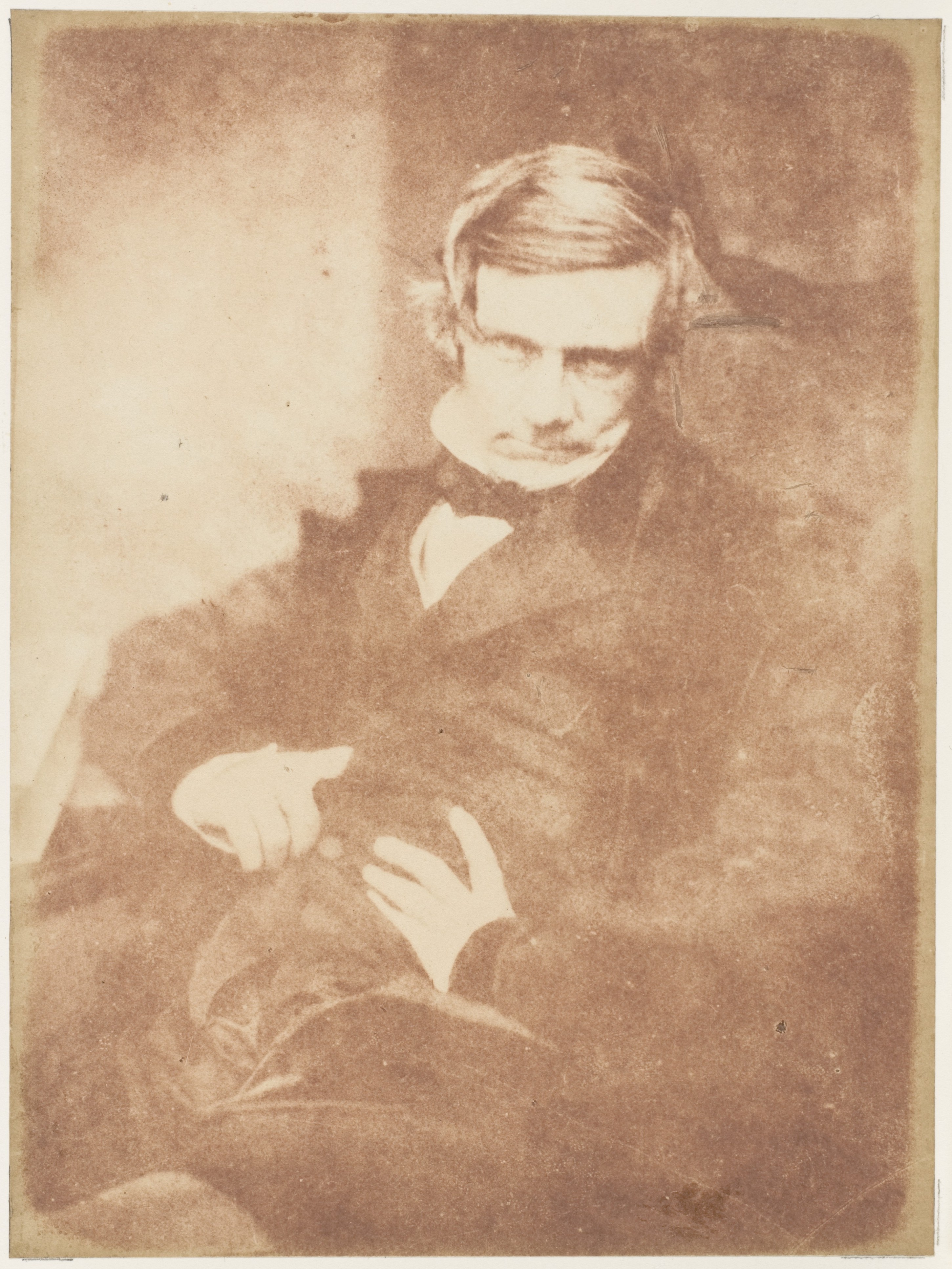

Thomas Duncan and His Brother Photography Studio Hill and Adamson British, Scottish David Octavius Hill British, Scottish Robert Adamson British, Scottish 1843–47

The Calotype devised by William Fox Talbot (11 February 1800 – 17 September 1877) aimed to improve things. “Upon hearing of the advent of the Daguerreotype in 1839,” writes Linz Welch at the United Photographic Artists Gallery, Talbot “felt moved to action to fully refine the process that he had begun work on. He was able to shorten his exposure times greatly and started using a similar form of camera for exposure on to his prepared paper negatives.”

The Calotype’s shortened exposure times produced images like the 1843 photo at the top of this page of people enjoying life in a pub in Scotland. It was taken by Adamson, whose older bother John, a professor of chemistry, was a friend of Talbot’s. You can see Hill on the right of the trio drinking beer. He seems to be in motion. This photograph is said to be the first image of alcoholic consumption.

The other two figures in the photograph are James Ballantine (left), a writer, stained-glass artist, and the son of an Edinburgh brewer, and Dr. George Bell (middle), one of the commissioners of the Poor Law of 1845, which reformed poor relief in Scotland.

The National Galleries of Scotland attributes the naturalness of these poses to “Hill’s sociability, humour and his capacity to gauge the sitters’ characters.” They had also been scarfing strong Edinburgh Ale, “a potent fluid, which almost glued the lips of the drinker together.”

The Calotypes are not as sharp as Daguerreotypes. Using paper as a negative meant that the paper’s texture and fibres were visible in prints made from it, leading to an image that was slightly grainy or fuzzy compared to Daguerreotypes. Although many people liked them for these very aesthetics.

The 42nd Gordon Highlanders, Edinburgh Castle

Dr. Latham – Editor of Dictionary

Lady Ruthven – ca. 1845

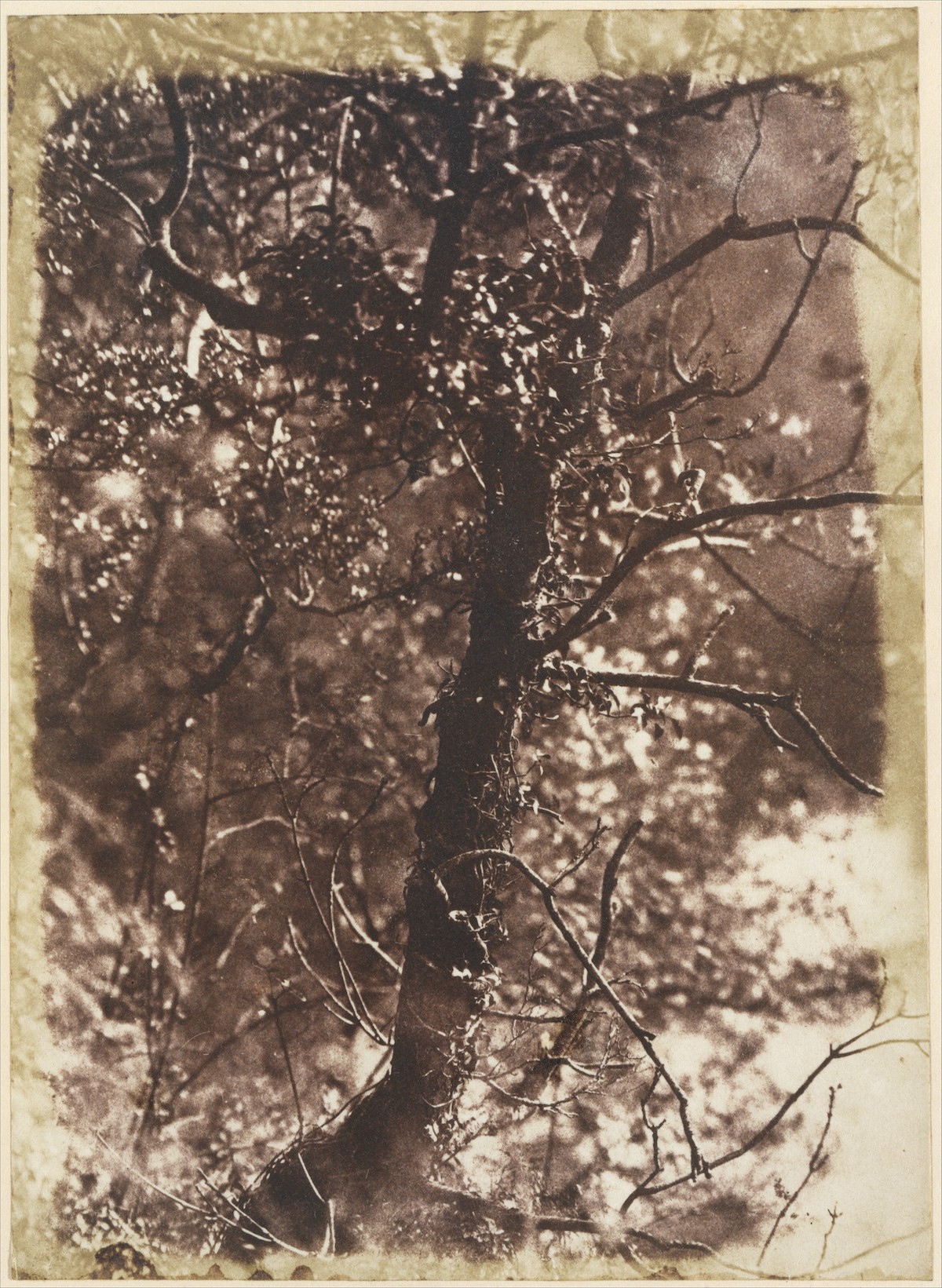

The Fairy Tree at Colinton – 1846

Afghans in armour, 1843

Hill’s membership in the Royal Scottish Academy gave the business partners access to a clientele of artists who sought photographic studies of posed models for their paintings. This photograph was likely a commission from the academy’s president Sir William Allan, who had collected exotic costumes and armor while traveling through Russia. During the 1840s Allan exhibited a series of Orientalist paintings depicting Circassians, an ethnic group from the Northern Caucasus. Here subtle shadows obscure the models’ faces, lending an air of mystery and drama to the imposing armor-clad figures.

[Newhaven Fishwives] Photography Studio Hill and Adamson British, Scottish David Octavius Hill British, Scottish Robert Adamson British, Scottish ca. 1845

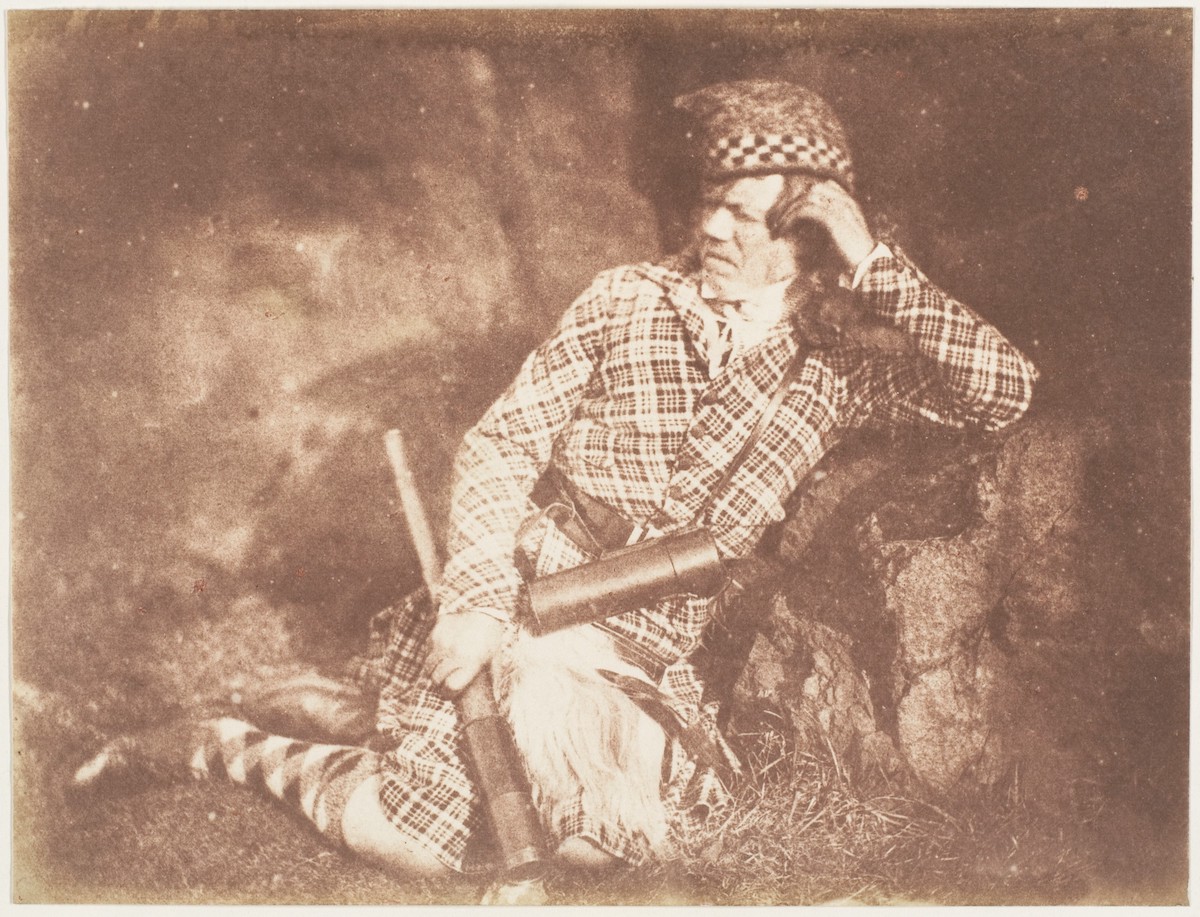

Finlay – The Deerstalker

The Misses McCandlish

We can make any of these images and more into prints, cards, postcards and, well, lot of things for the shop, the you get in touch via the chatbox.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.