‘Throw your arms across your eyes and scream, Ann. Scream for your life!’

— Carl Denham, King Kong, 1933

The battle of the century is upon us, Godzilla vs. King Kong, but then, of course, the two giants met nearly 60 years earlier “in what Toho called the ‘battle of the century,’” Nicholas Raymond writes at Screenrant. Curiously, in that film, the Japanese studio let the Hollywood ape, on loan from RKO Pictures, defeat their star. But both monsters were only two films into their long, illustrious careers, and Godzilla had not yet acquired his reputation as an “anti-hero who fights off bigger threats to Japan.”

Kong, by contrast, “had a much different reputation.” The prehistoric throwback “was incredibly popular, and this was true in Japan as well… It’s important to keep in mind that though Kong wasn’t necessarily a hero, he was seen as a sympathetic figure.” Kong’s death, though inevitable in the first 1933 film, was framed as tragic from his earliest beginnings, setting a tone became even more pronounced in subsequent iterations. Kong is misunderstood: his instinct is protective rather than destructive.

Merian C. Cooper at the Latvian border after his time in a Soviet POW camp

This sympathetic thread in the character’s portrayal complicates criticism of the film as an inherently racist allegory. Kong is a confused exotic fantasy, conceived by adventurers and sold to audiences who were all raised on adventure tales about the fauna of “darkest Africa” and other parts of the world where dragons there might be. King Kong’s creator Merian C. Cooper (October 24, 1893 – April 21, 1973) was himself the kind of old-fashioned swashbuckler who appeared in pulp novels, the model for Carl Denham in the film.

Born in Jacksonville, Florida, Cooper “went on to become a globetrotting adventurer,” says biographer Ray Morton, “a really colorful guy. He was a war hero. He had been shot down a couple of times in both World War I and in the Polish-Russo War.” He had also traveled the world on safari adventures, pursuing tigers and rhinos. Cooper’s original intentions in the fight scenes was to have an actual gorilla fight a komodo dragon.

But Kong is also undeniably part and parcel of a legacy of colonialist tropes that mapped bestial qualities onto non-white peoples. “The romantic might call [King Kong directors Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack] explorers and adventurers,” writes Colin McMahon, “and they wouldn’t be completely wrong.” Others “would describe them as imperialists very comfortable with the exploitation” they encountered and perpetuated, and such critics “would not be wrong either.” As Nathan Rabin writes inVanity Fair, “perhaps the nicest thing that can be said about the racial politics of the original King Kong is that they reflect the tenor of the times, where were, alas, very racist.”

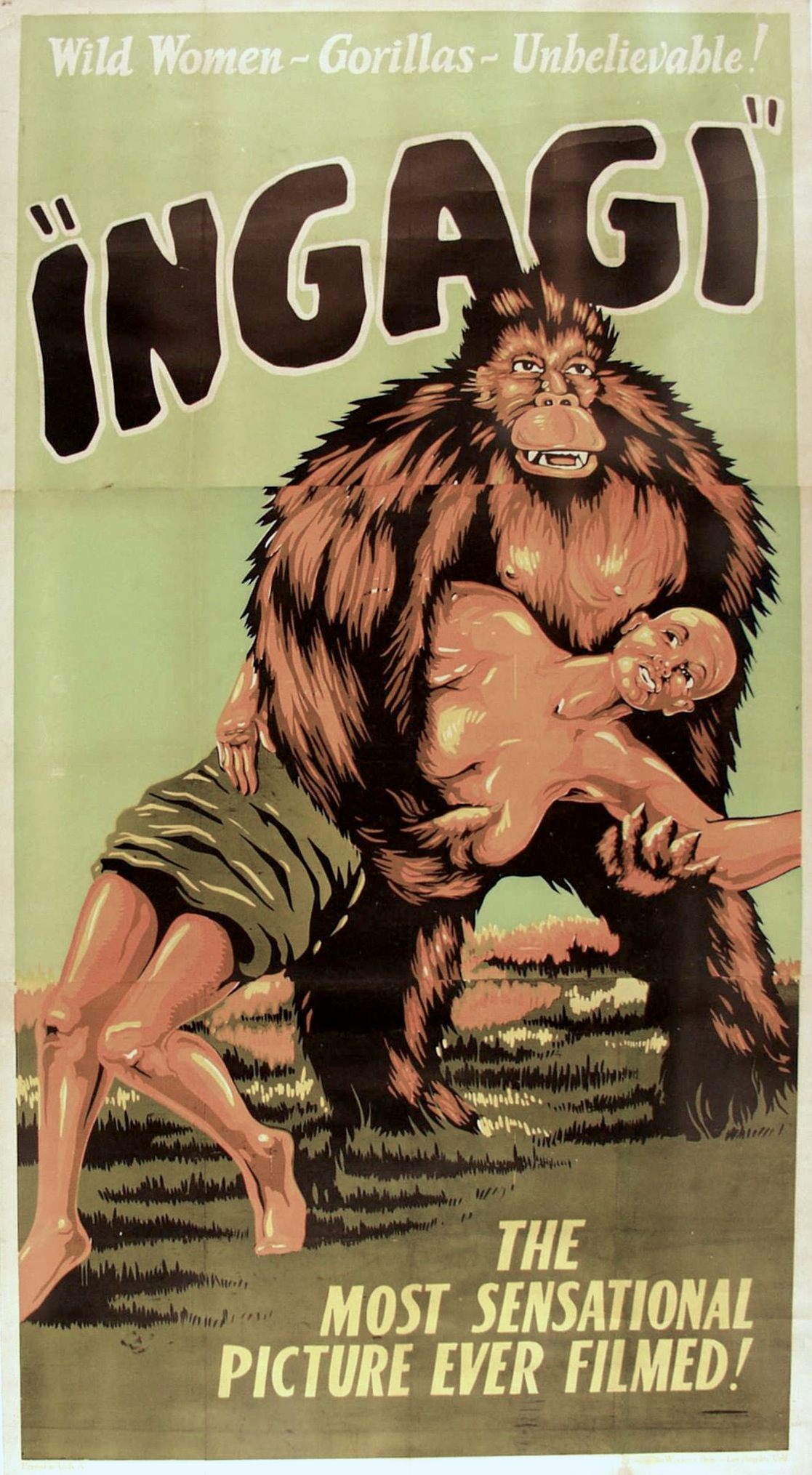

We might consider, for example, that Kong’s precursor was a 1930 film called Ingagi. Made in L.A. film lots with an African American cast and a man in a gorilla suit, the movie was sold as a documentary of a African tribe that offered up their women as sex slaves for an ape. Whatever Cooper and Schoedsack’s intentions, Ingagi’s popularity convinced RKO Pictures to invest in King Kong, and Ingagi’s shocking bestiality (“Wild Women–Gorillas–Unbelievable!”) was fresh in audiences’ minds when the legendary 1933 monster movie came out.

Poster advertising Ingagi – 1930

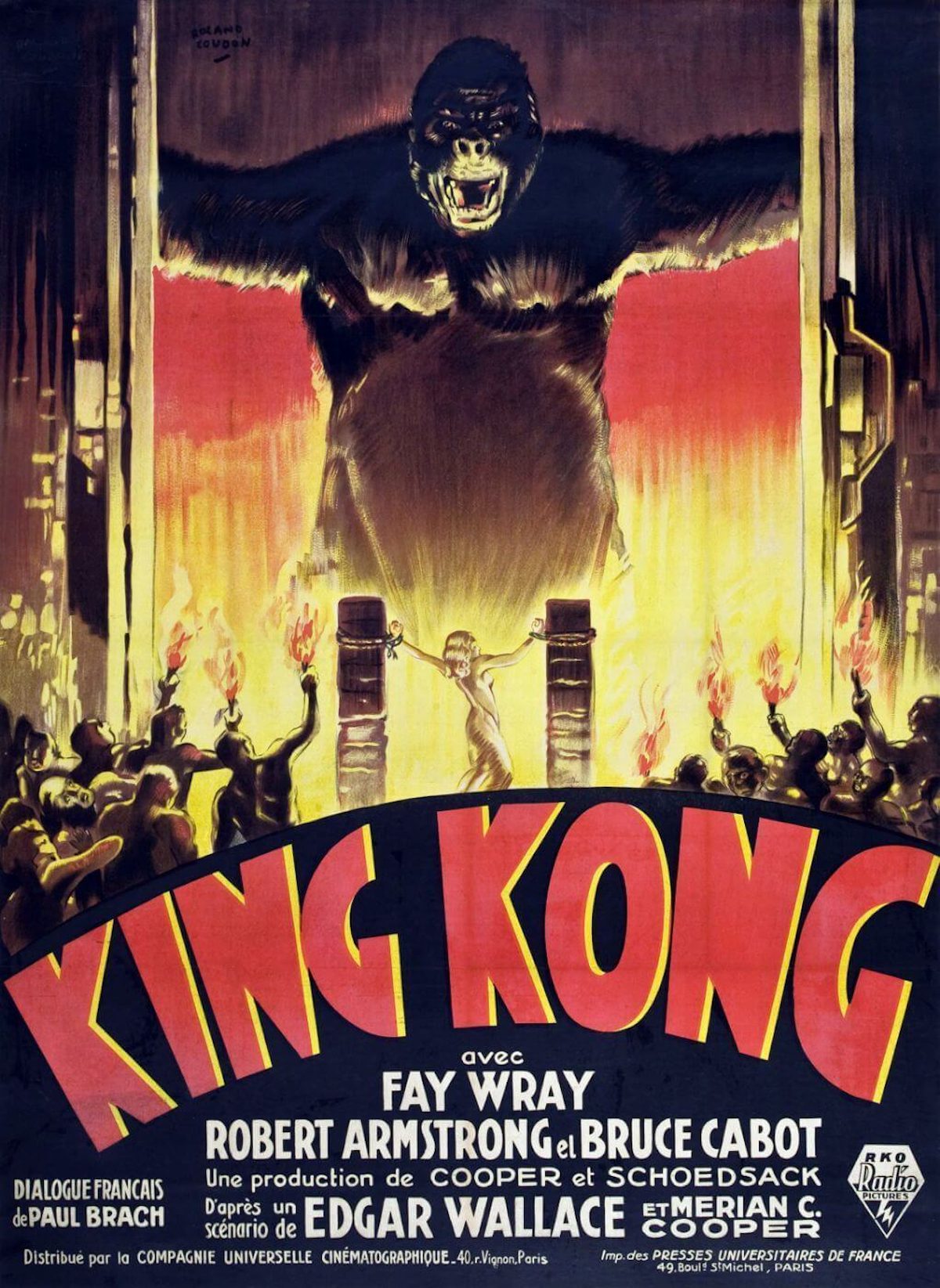

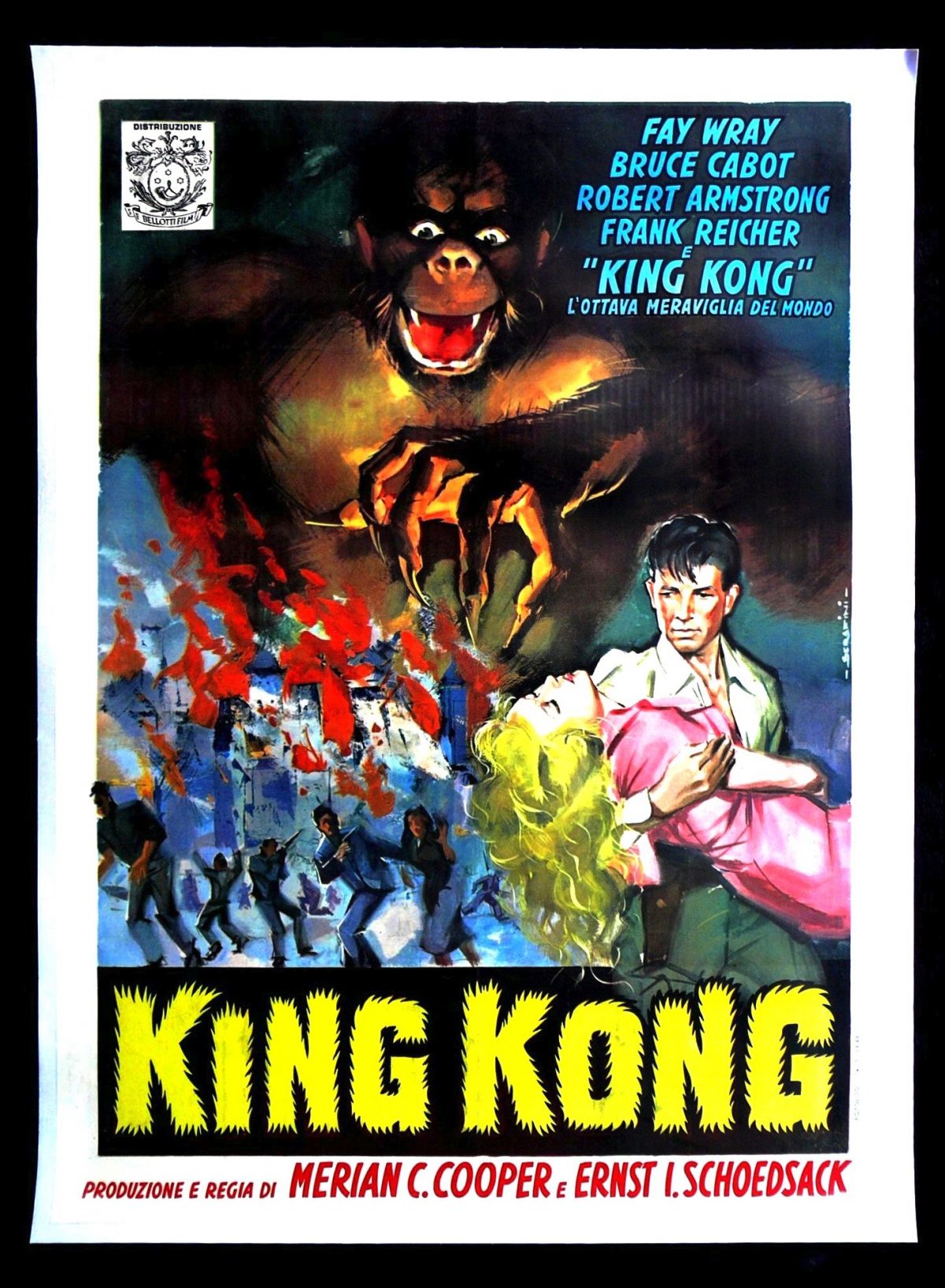

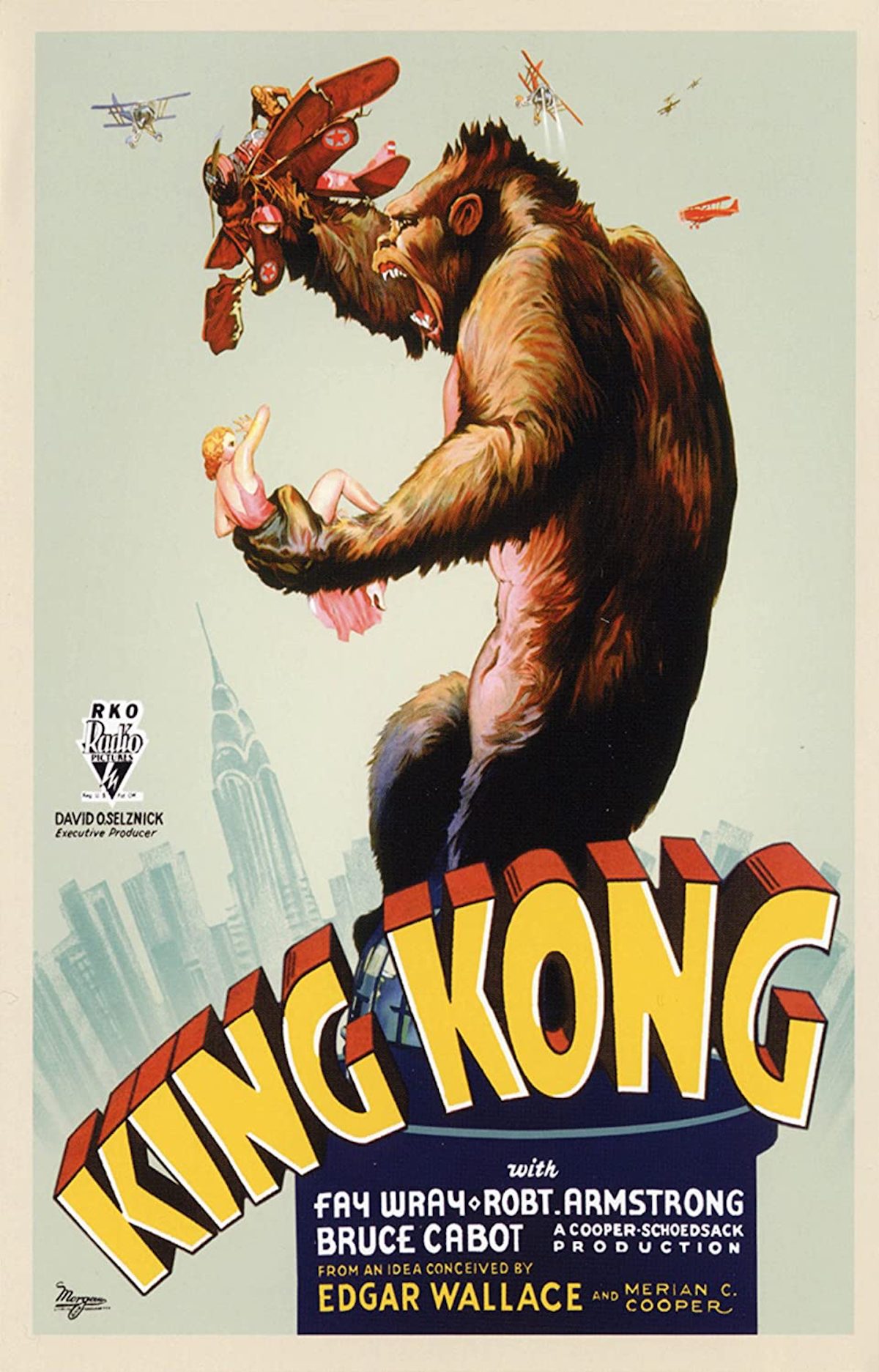

King Kong’s advertising didn’t trade on any associations with previous films, but it also rarely pictured the film’s actual monsters — because, as a contemporary reviewer at Time wrote, the monsters looked a bit ridiculous, even to 1933 audiences:

Kong is actually 50 ft. tall, 36 ft. around the chest. His face is 6½ ft. wide with 10-in. teeth and ears 1 ft. long. He has a rubber nose, glass eyes as big as tennis balls. His furry outside is made of 30 bearskins. During his tantrums, there were six men in his interior running his 85 motors. Naturally no such monster would be limber enough to wrestle with a tyrannosaurus. Most of Kong’s fights were photographed in miniature, some of them in “stop-motion”—using models of which the positions are minutely changed after each exposure, like the drawings in an animated cartoon.

A Variety reviewer sounded equally underwhelmed, writing, “after the audience becomes used to the machine-like movements and other mechanical flaws in the gigantic animals on view, and become accustomed to the phoney atmosphere, they may commence to feel the power.”

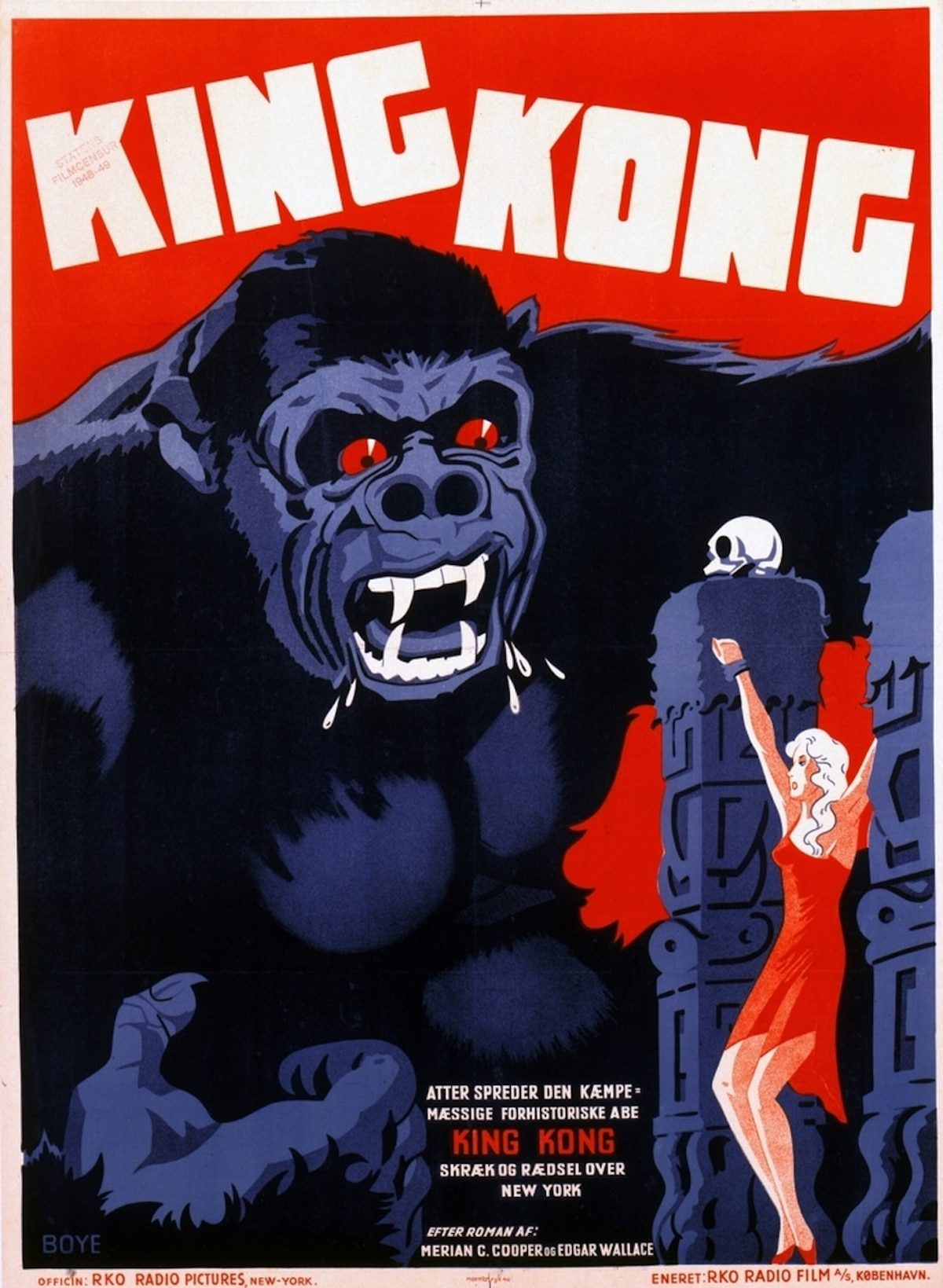

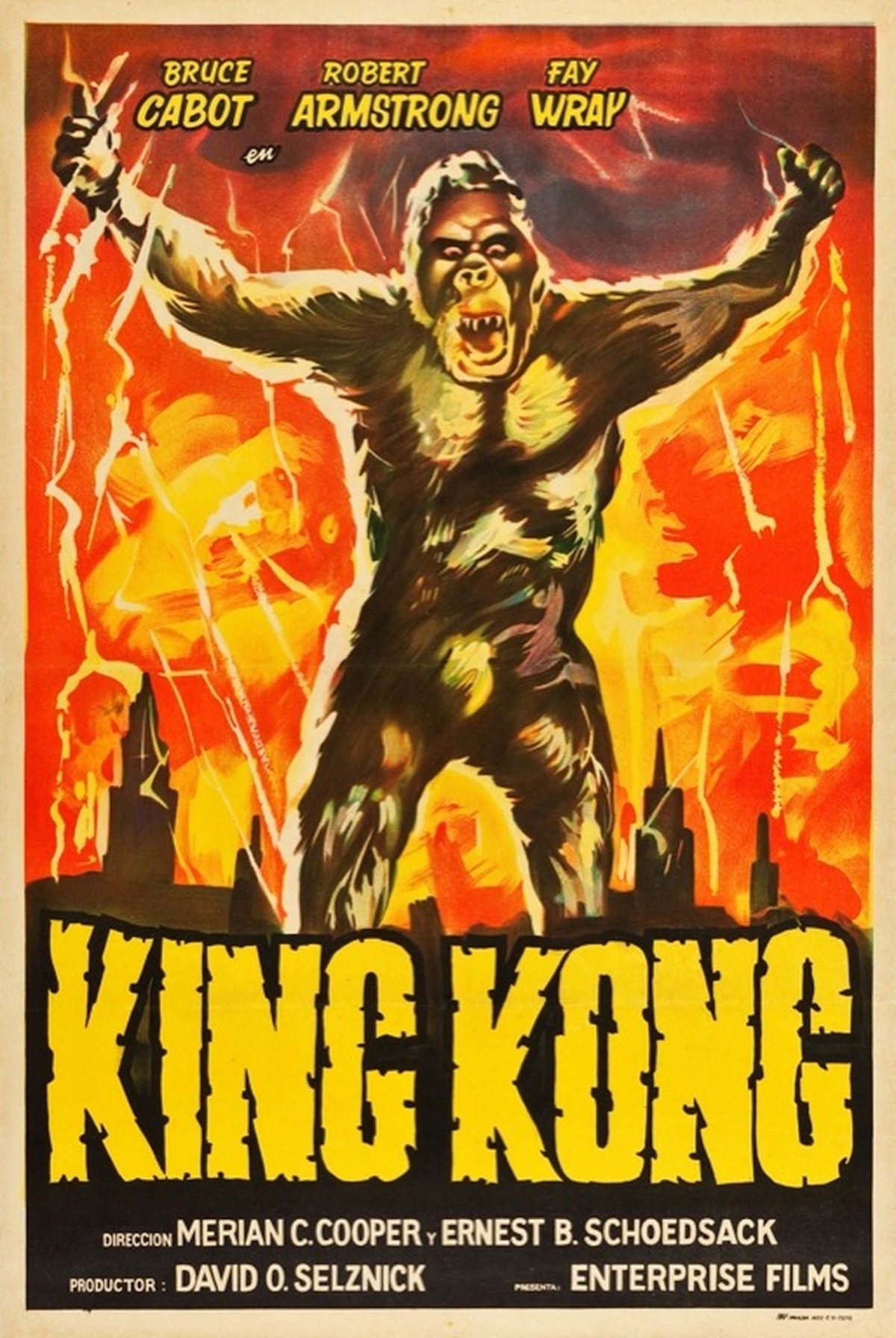

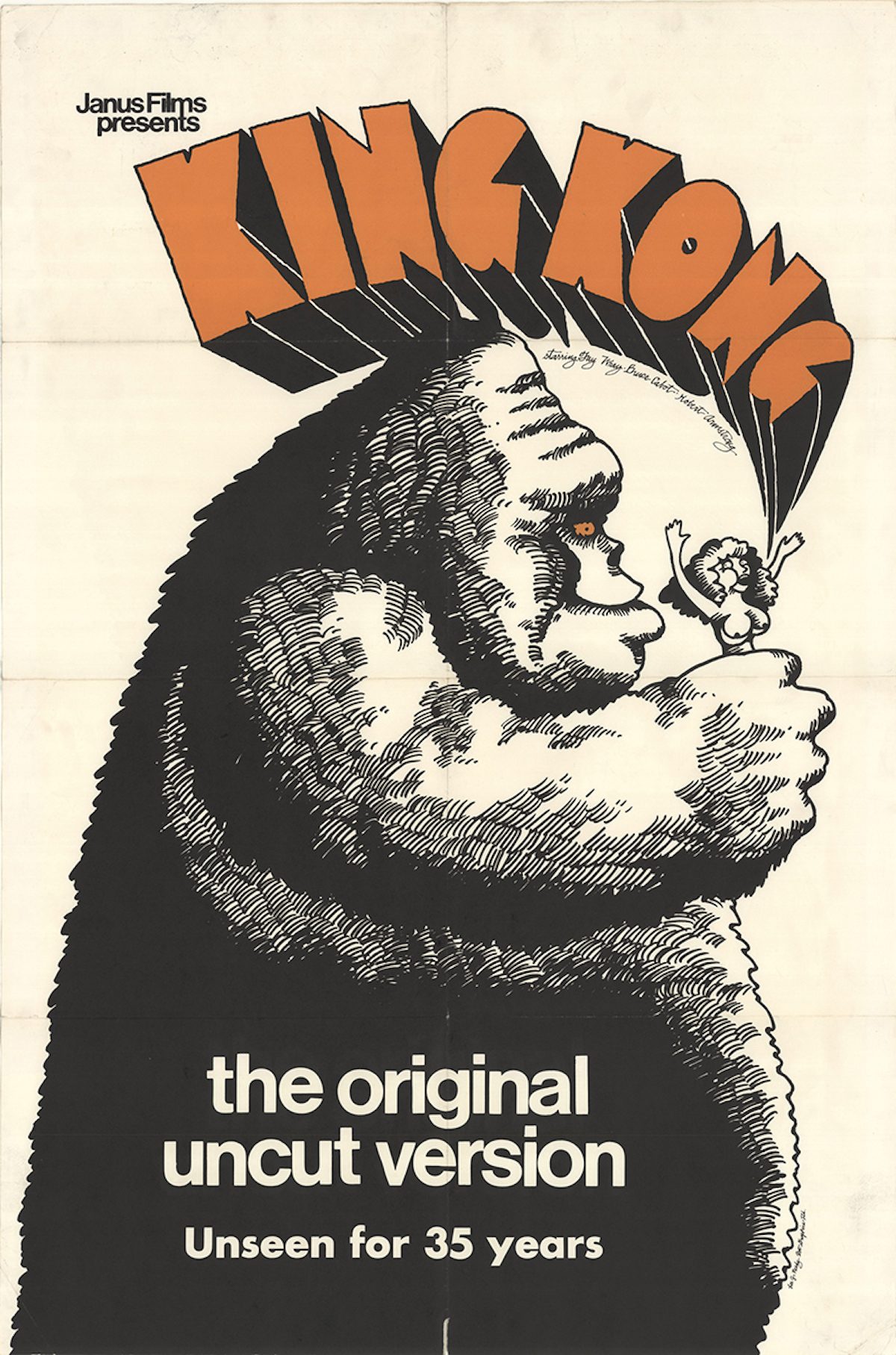

If the huge, motorized Kong and Ray Harryhousen’s stop-motion animations weren’t enough to entice audiences into theaters on movie posters, what was? Kong’s creator wasn’t only a swashbuckling adventurer like Carl Denham, but he was also a grand promoter. The film’s poster art and promotional language gave potential viewers a ravenous beast, sometimes more chimpanzee than gorilla – the threat sometimes more, sometimes less sexualized – without a hint of clunkiness or a hidden heart of gold.

Various degrees of xenophobia and racial panic probably have inspired each of the international promotional campaigns. But while the film contains unsurprising racial caricatures, it doesn’t explicitly trade on them. But it’s telling that the poster used to promote King Kong in Nazi Germany essentially re-titles the film what might translate to“King Kong and the White Woman.” In a 1968 poster advertising the original film’s restoration and re-release, a busty cartoon Fay Wray bursts out of her clothing, and King Kong looks like the cutest, cuddliest creature in the world.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.