“Hope is the thing with feathers

That perches in the soul

And sings the tune without the words

And never stops at all.”— Emily Dickinson

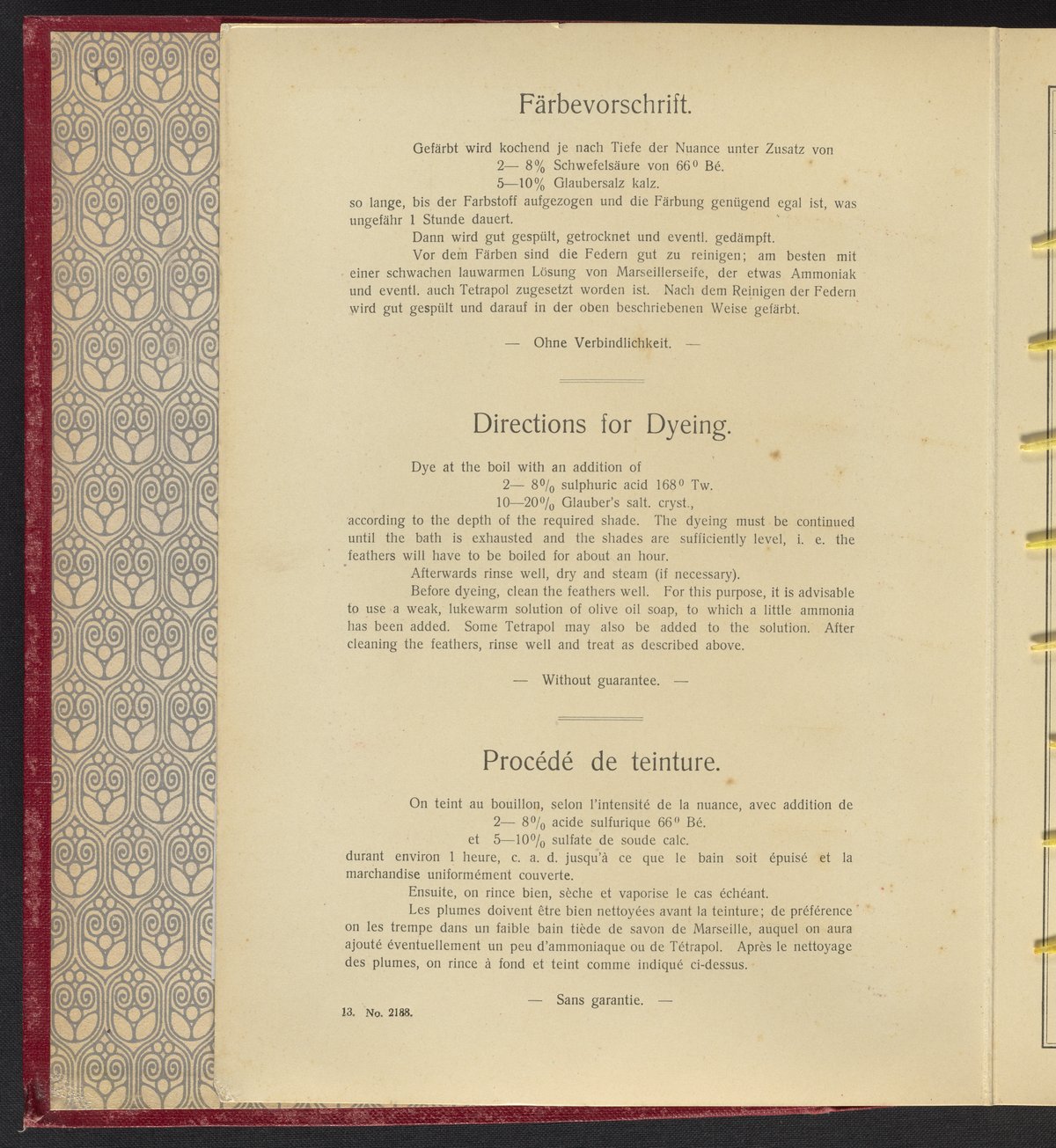

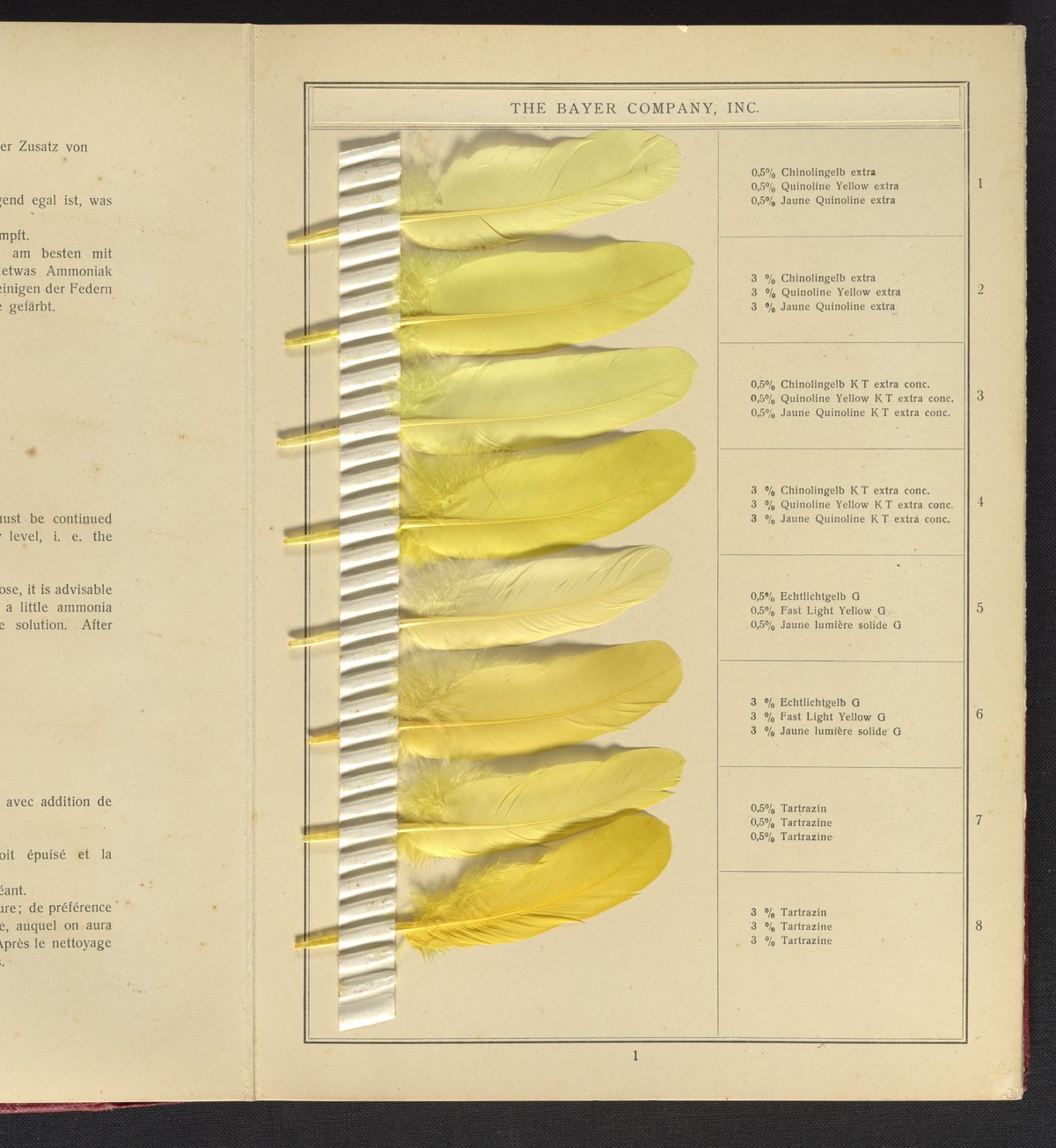

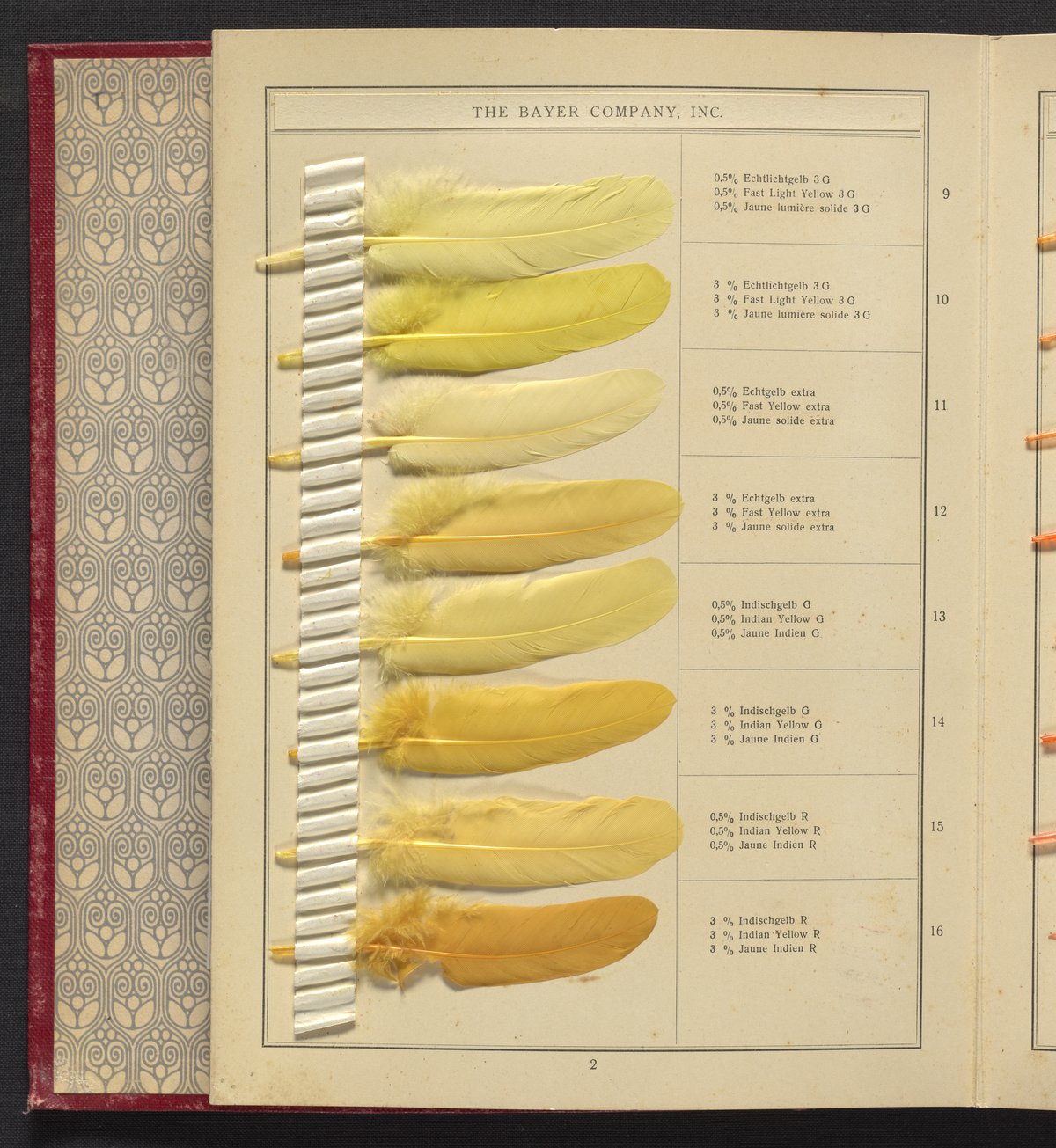

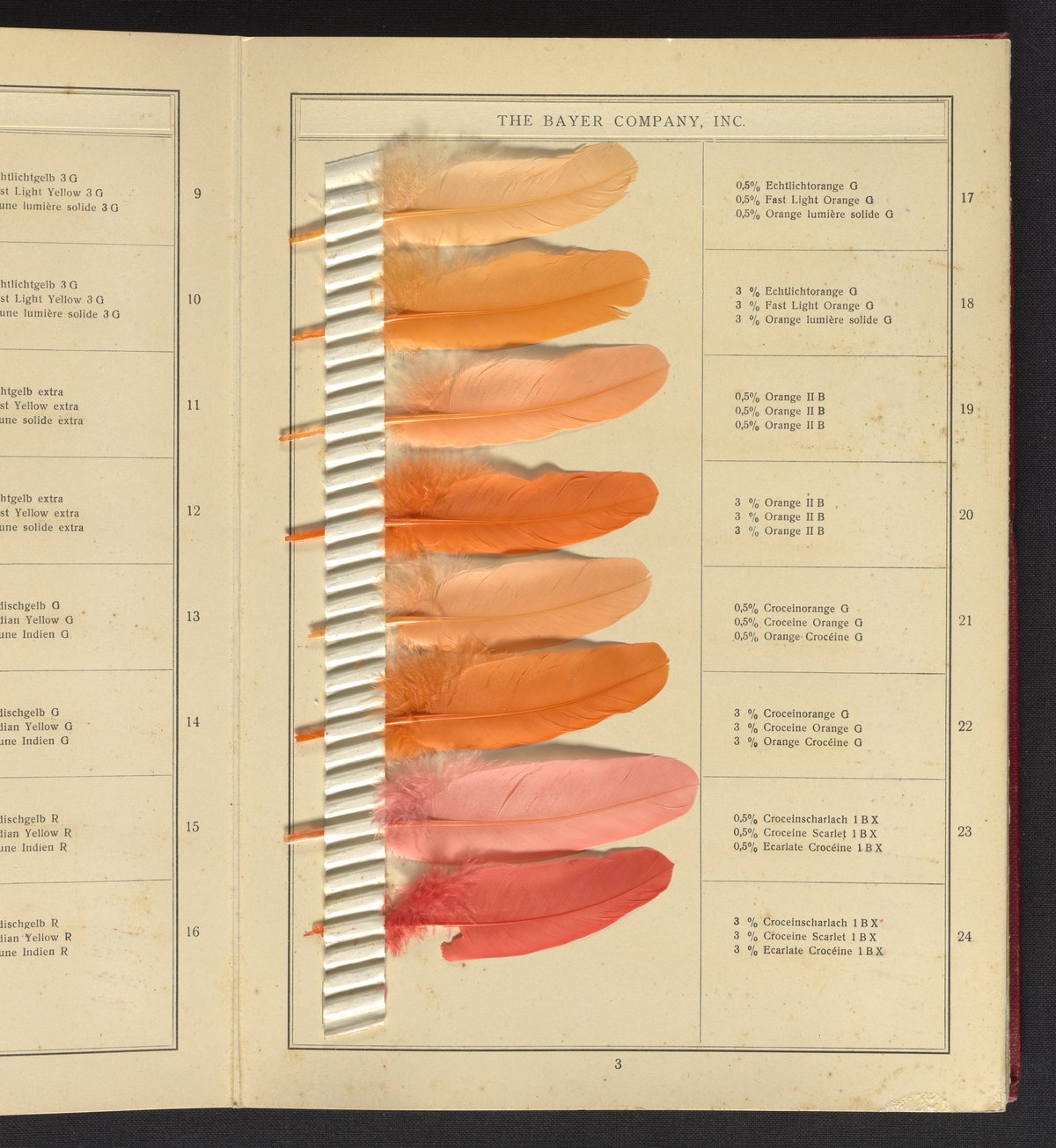

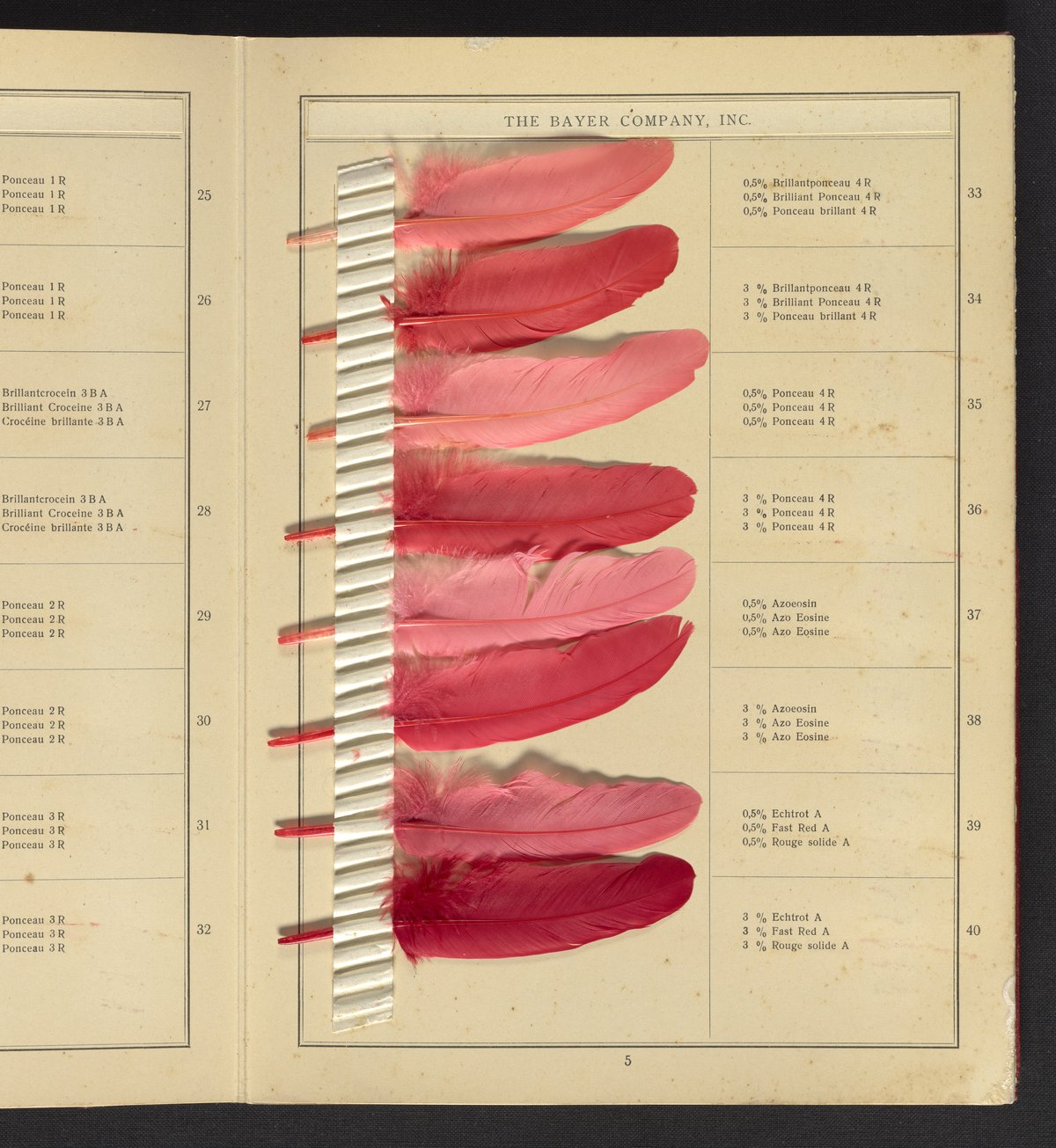

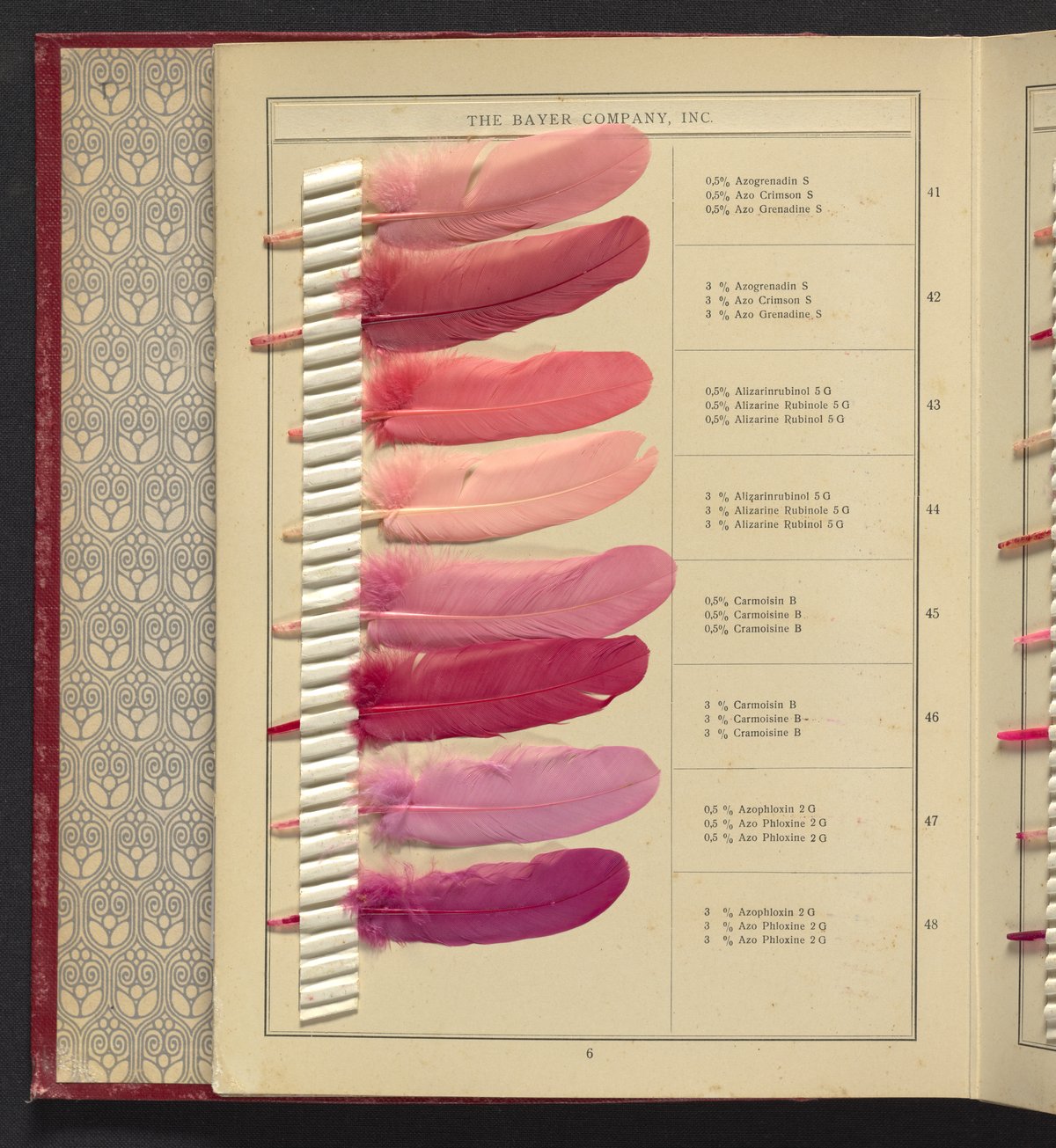

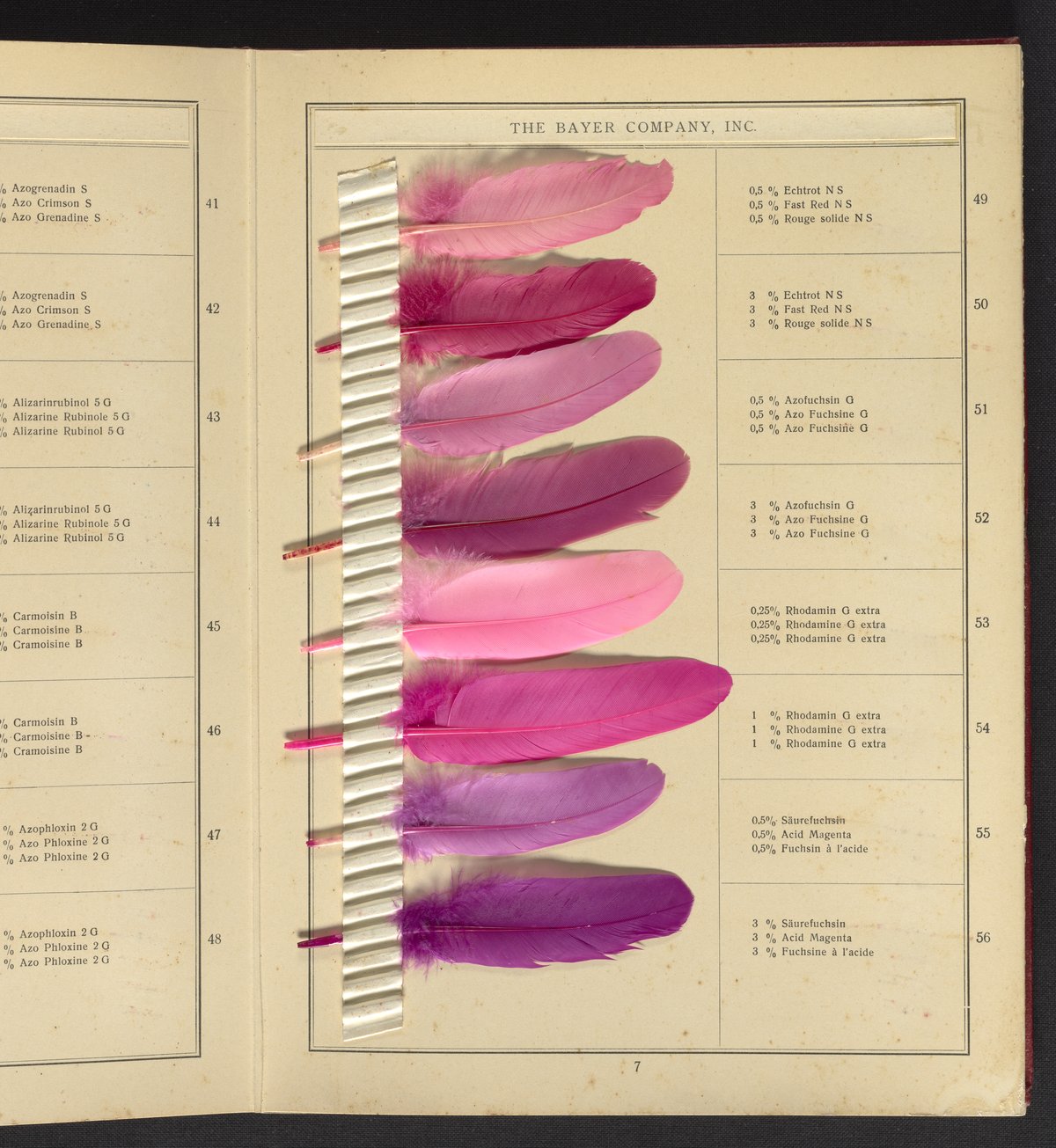

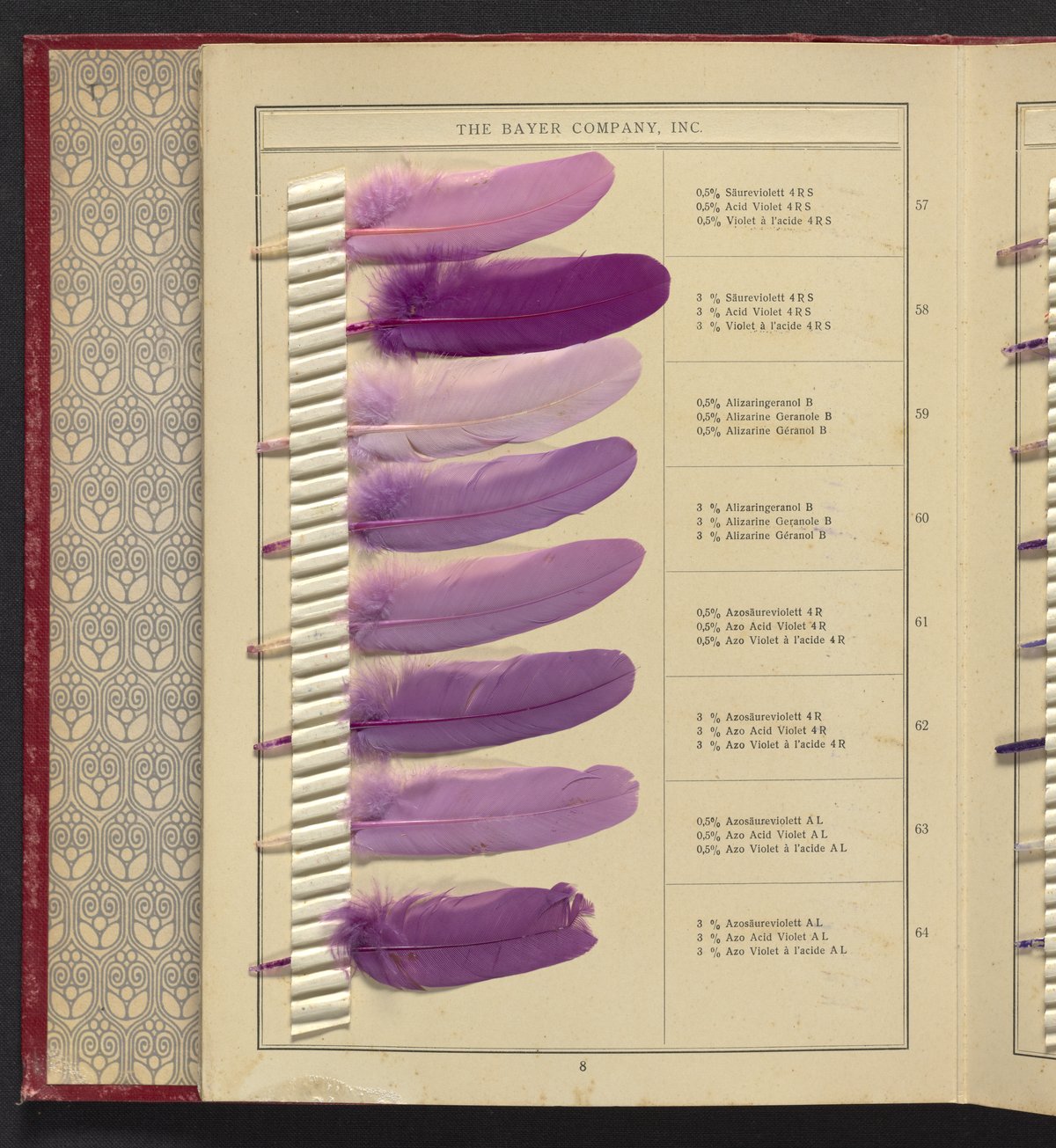

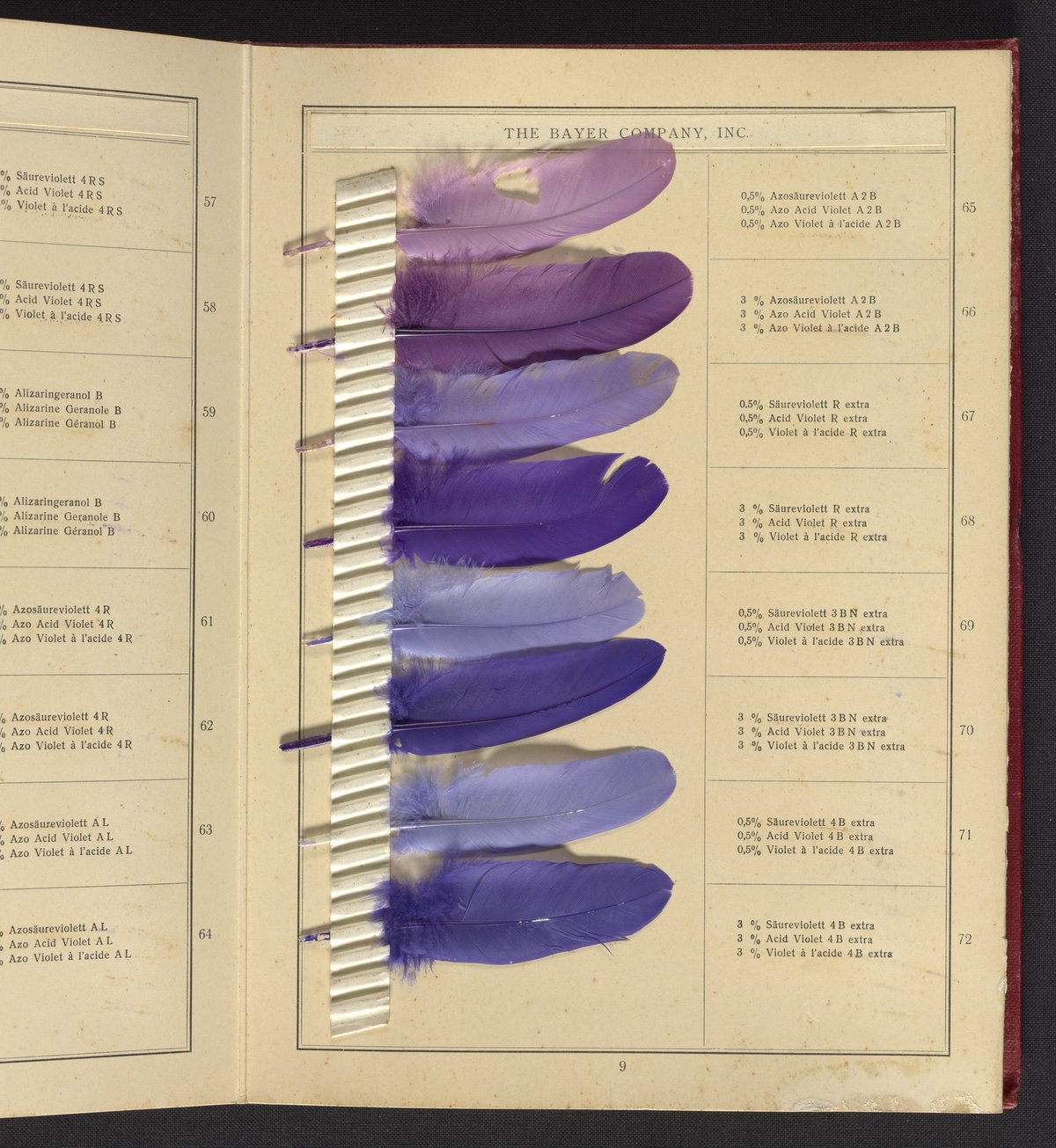

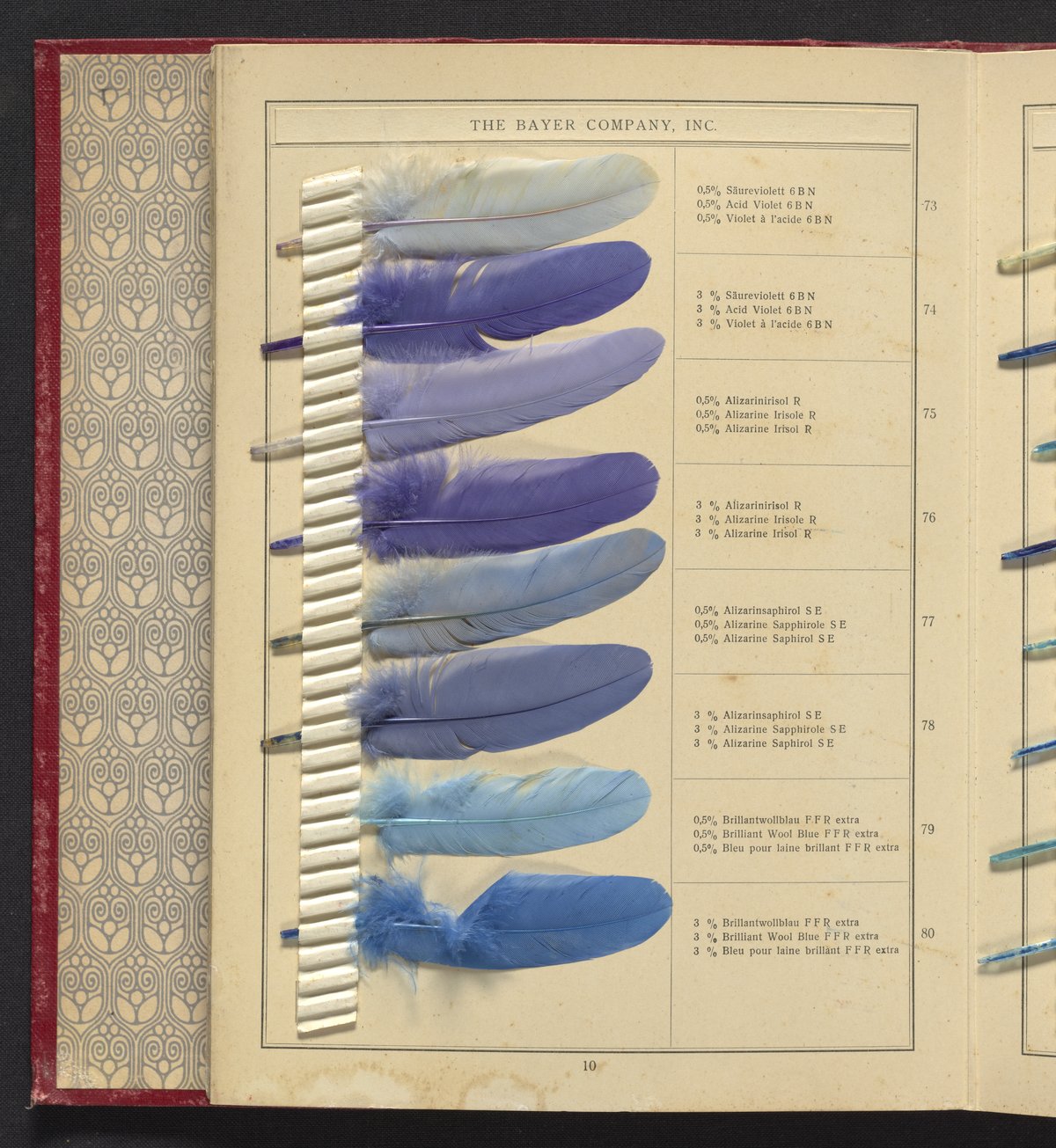

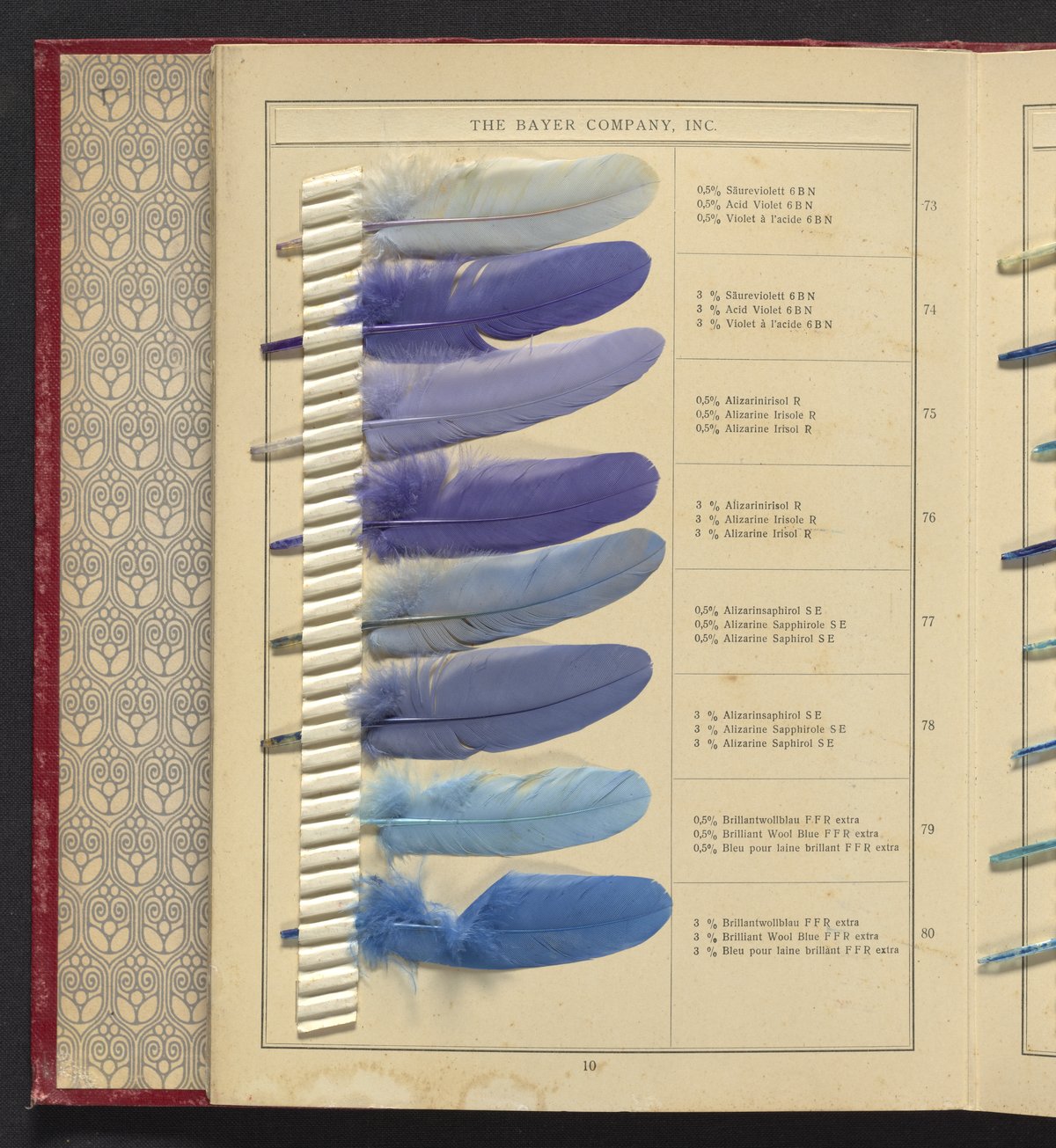

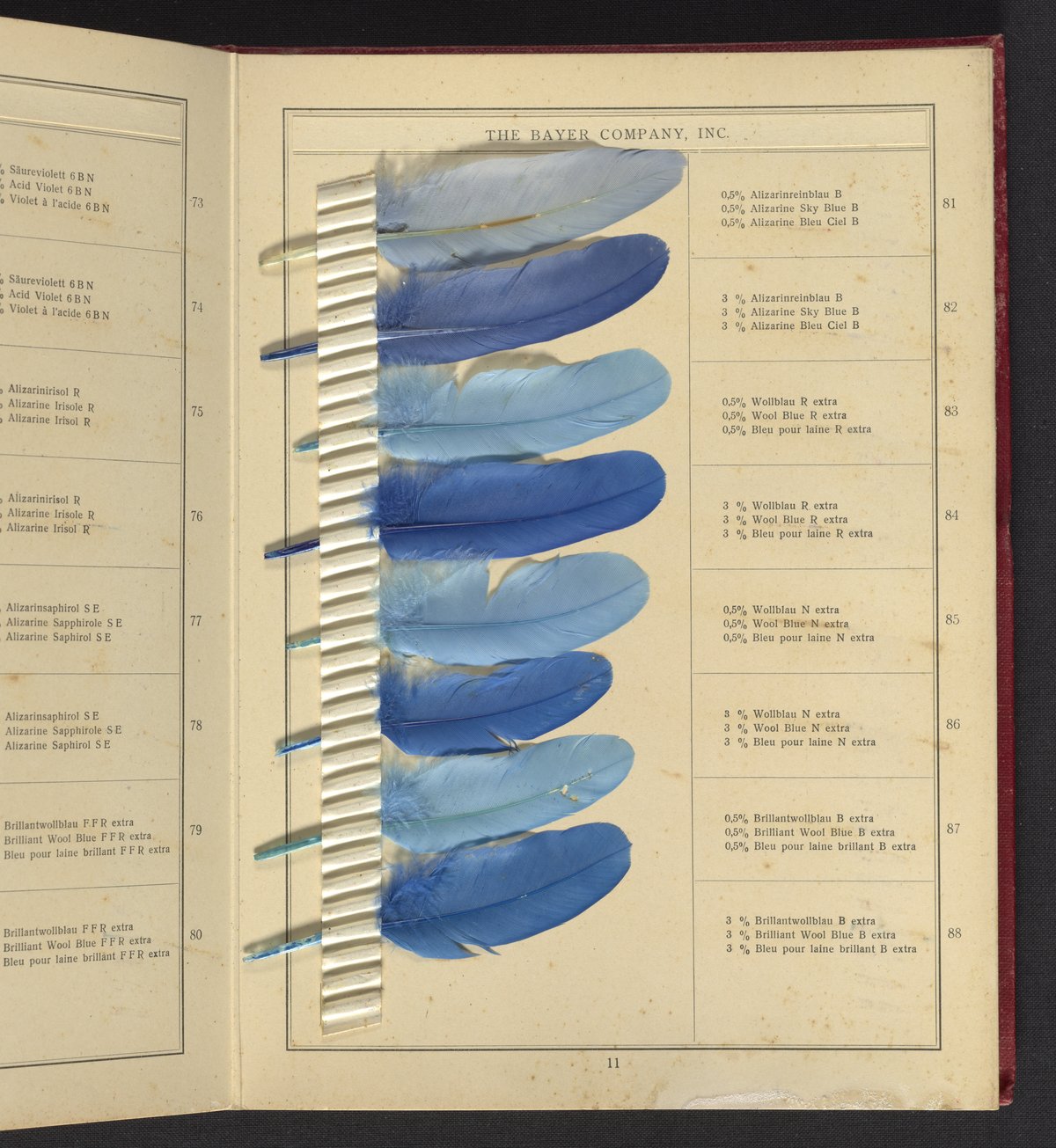

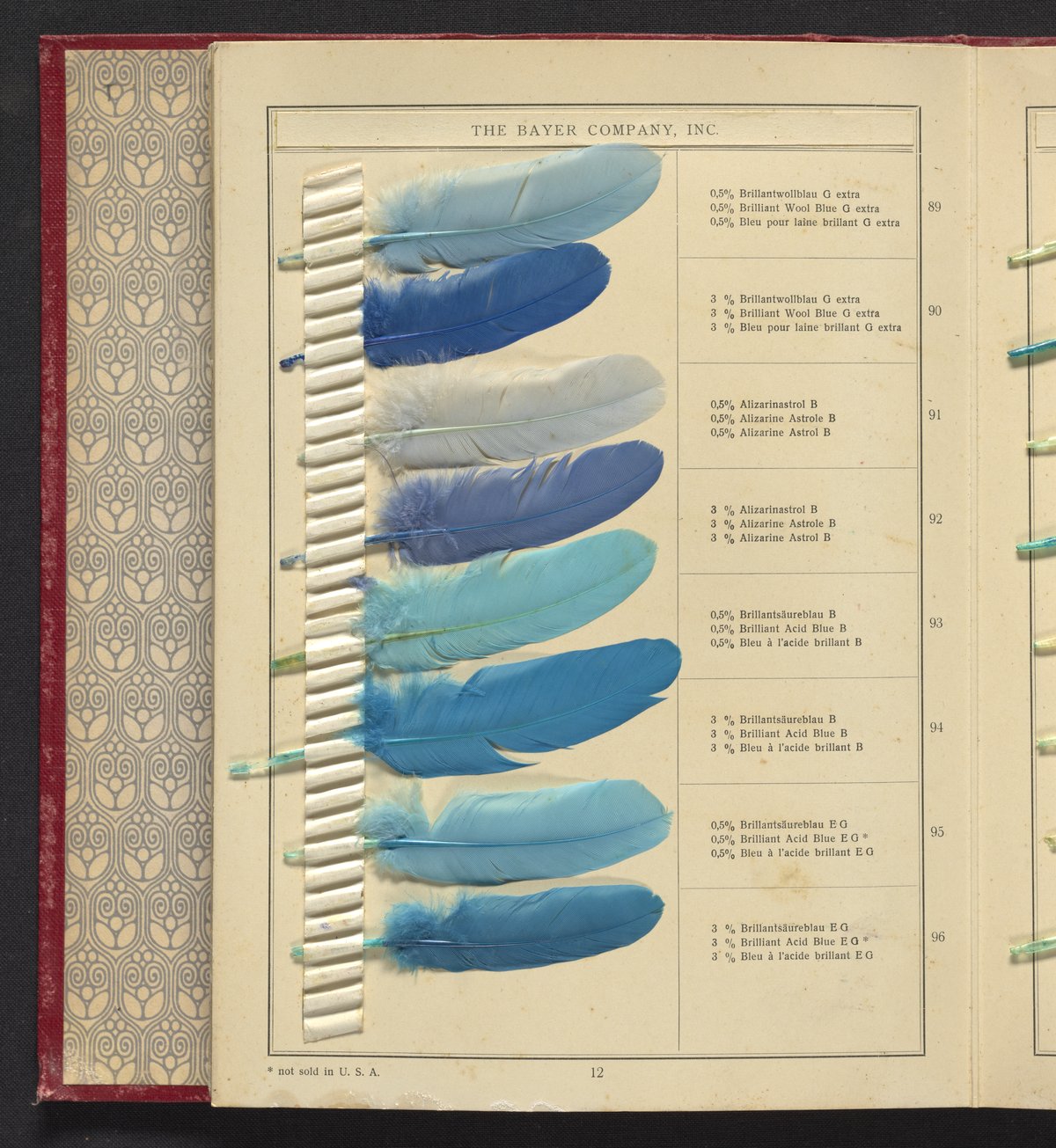

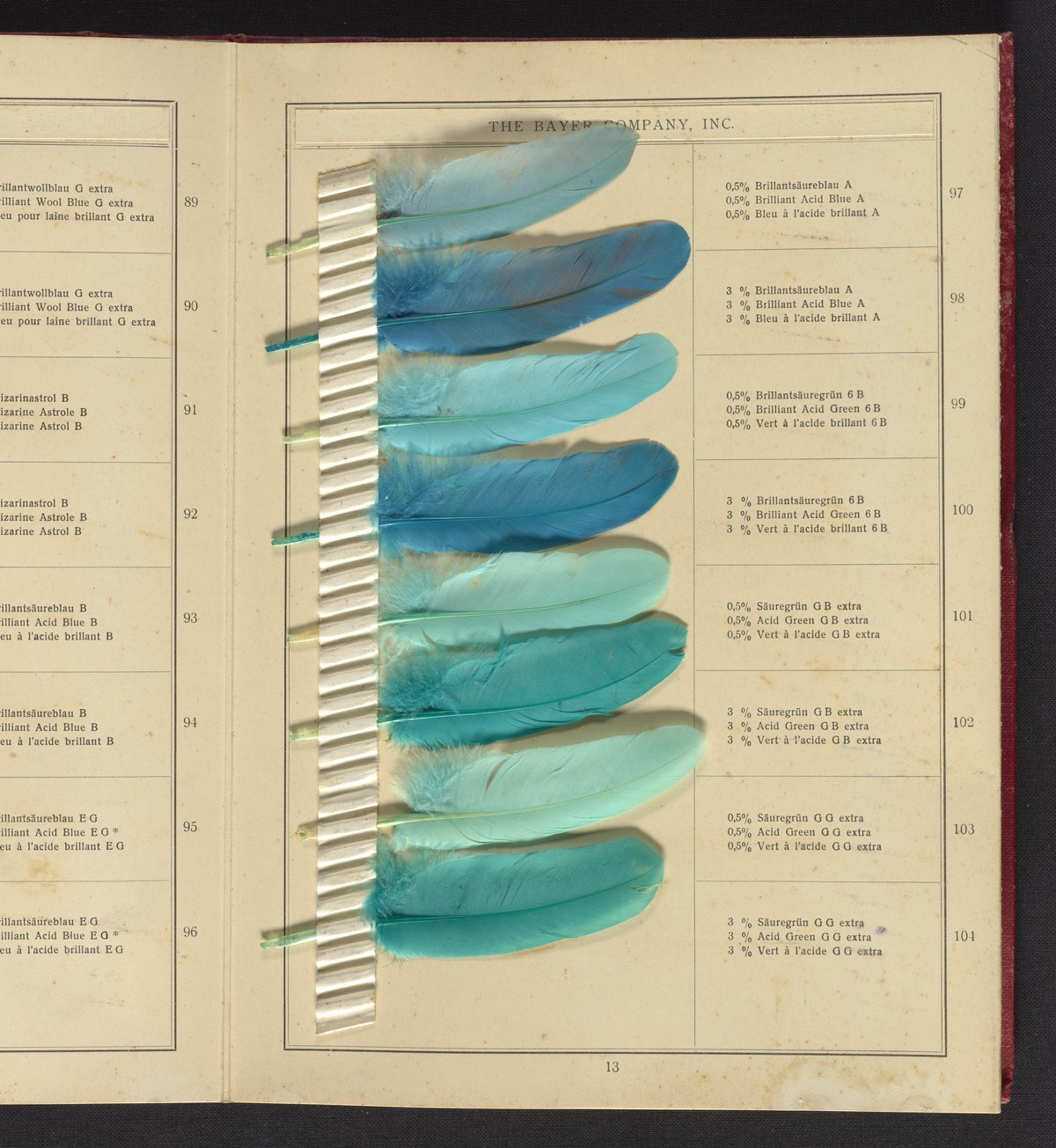

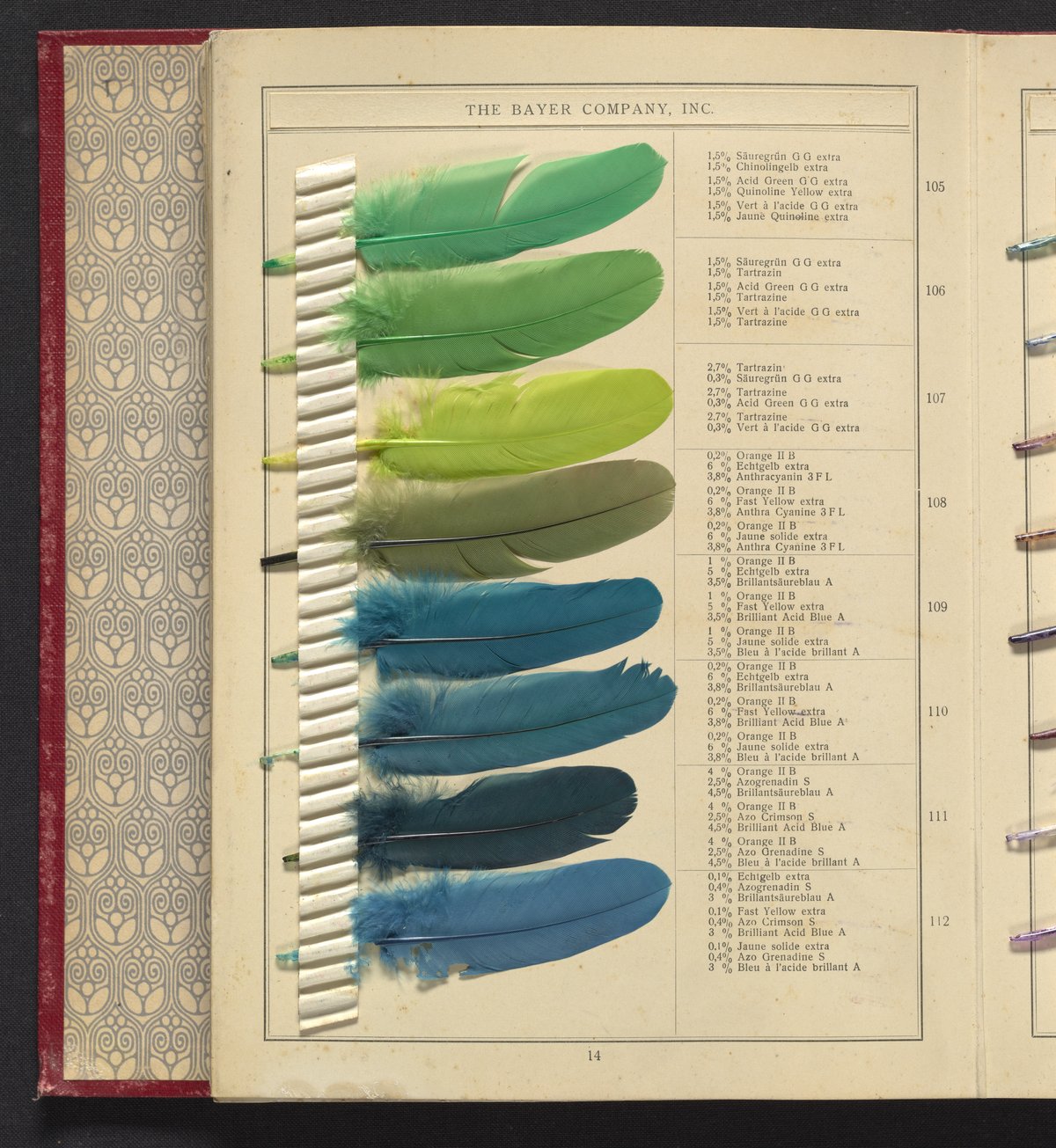

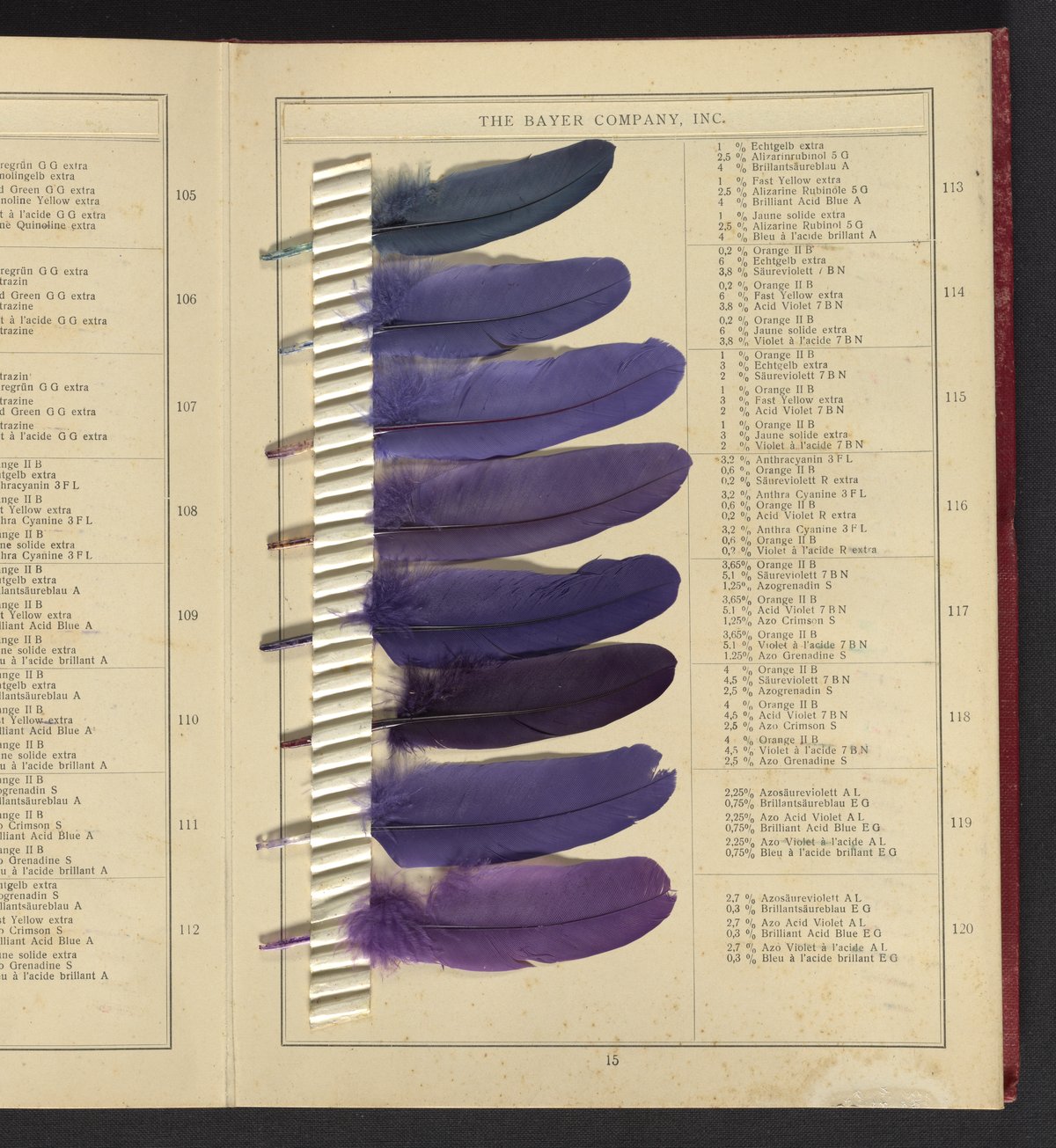

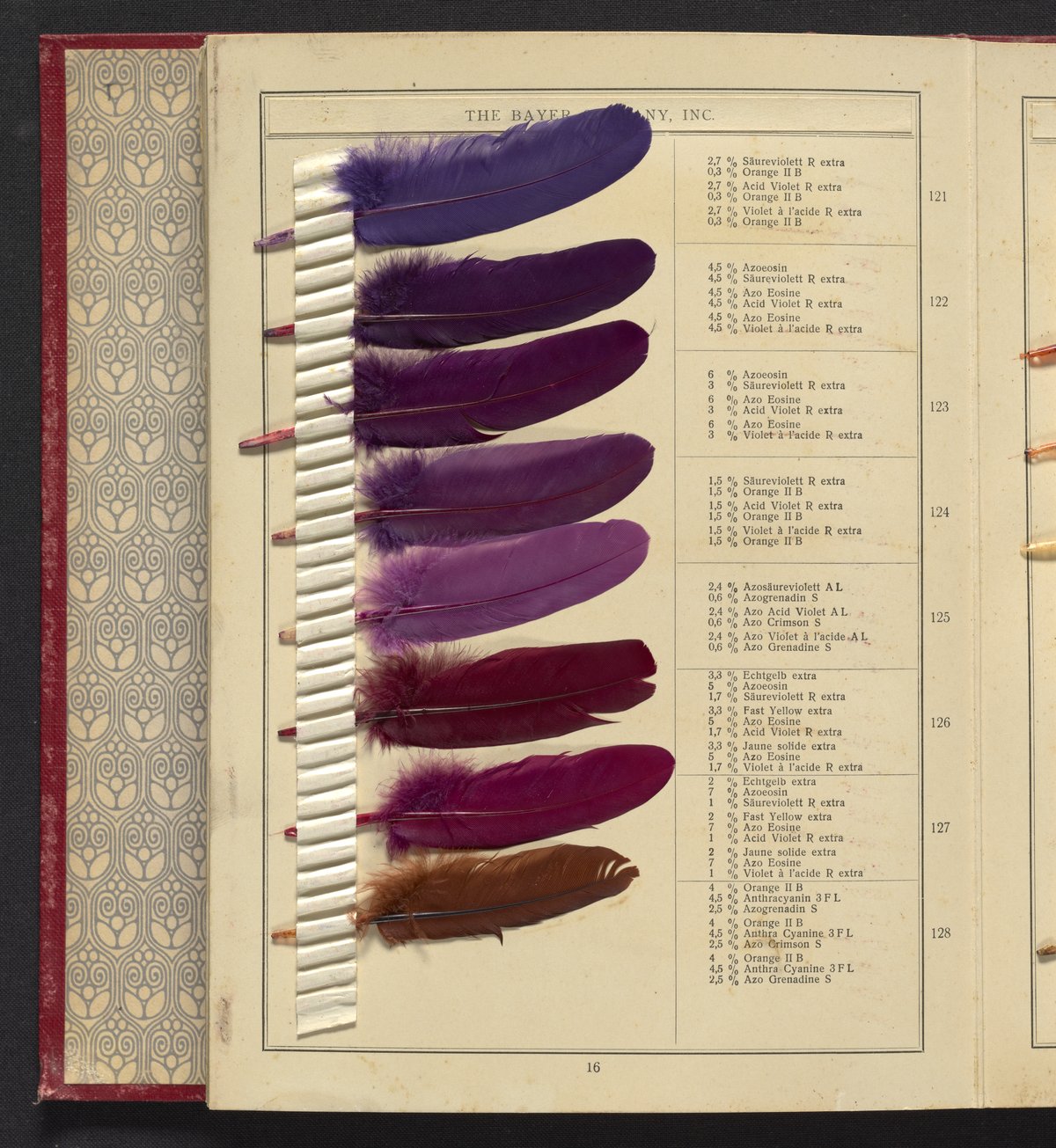

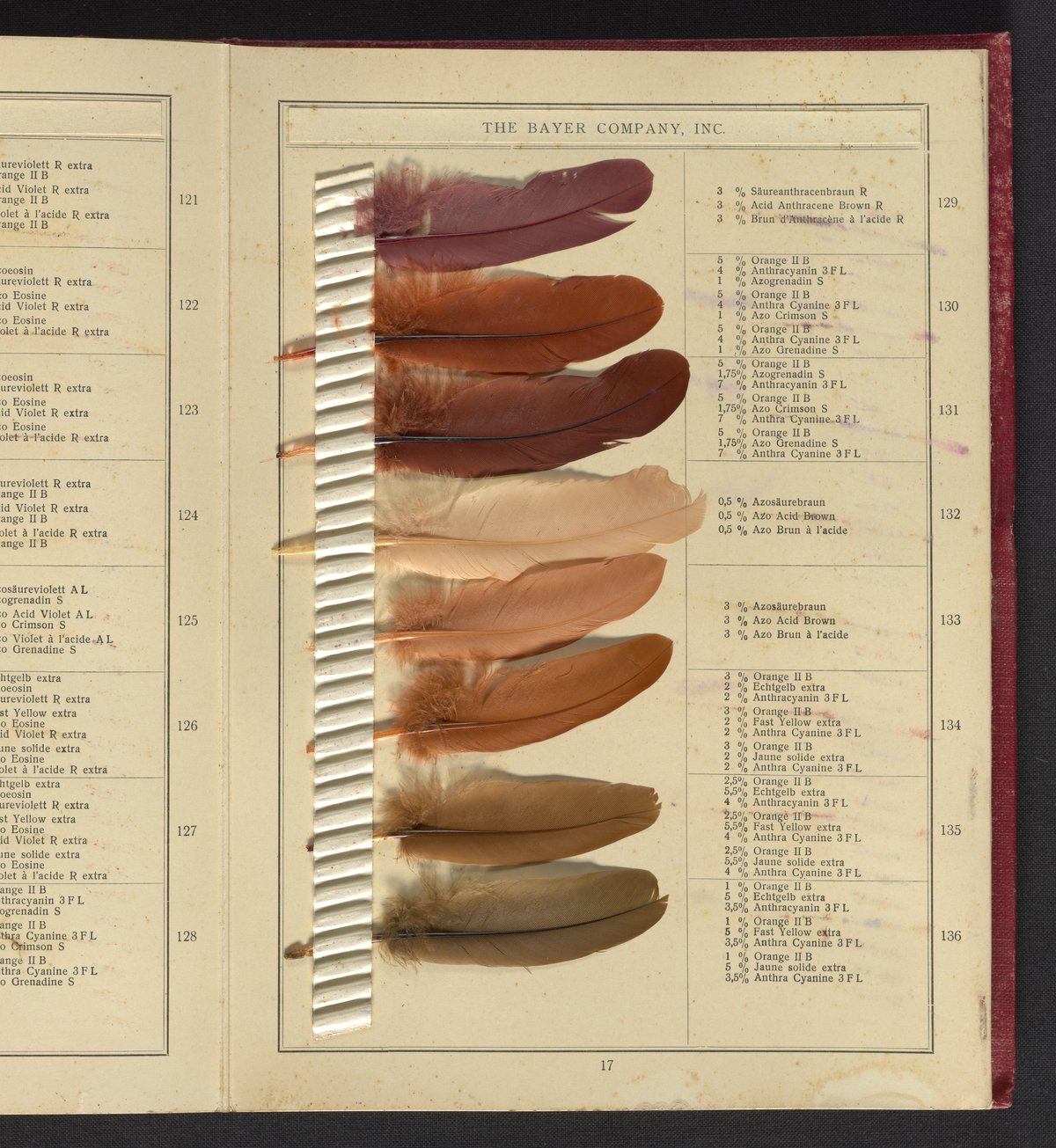

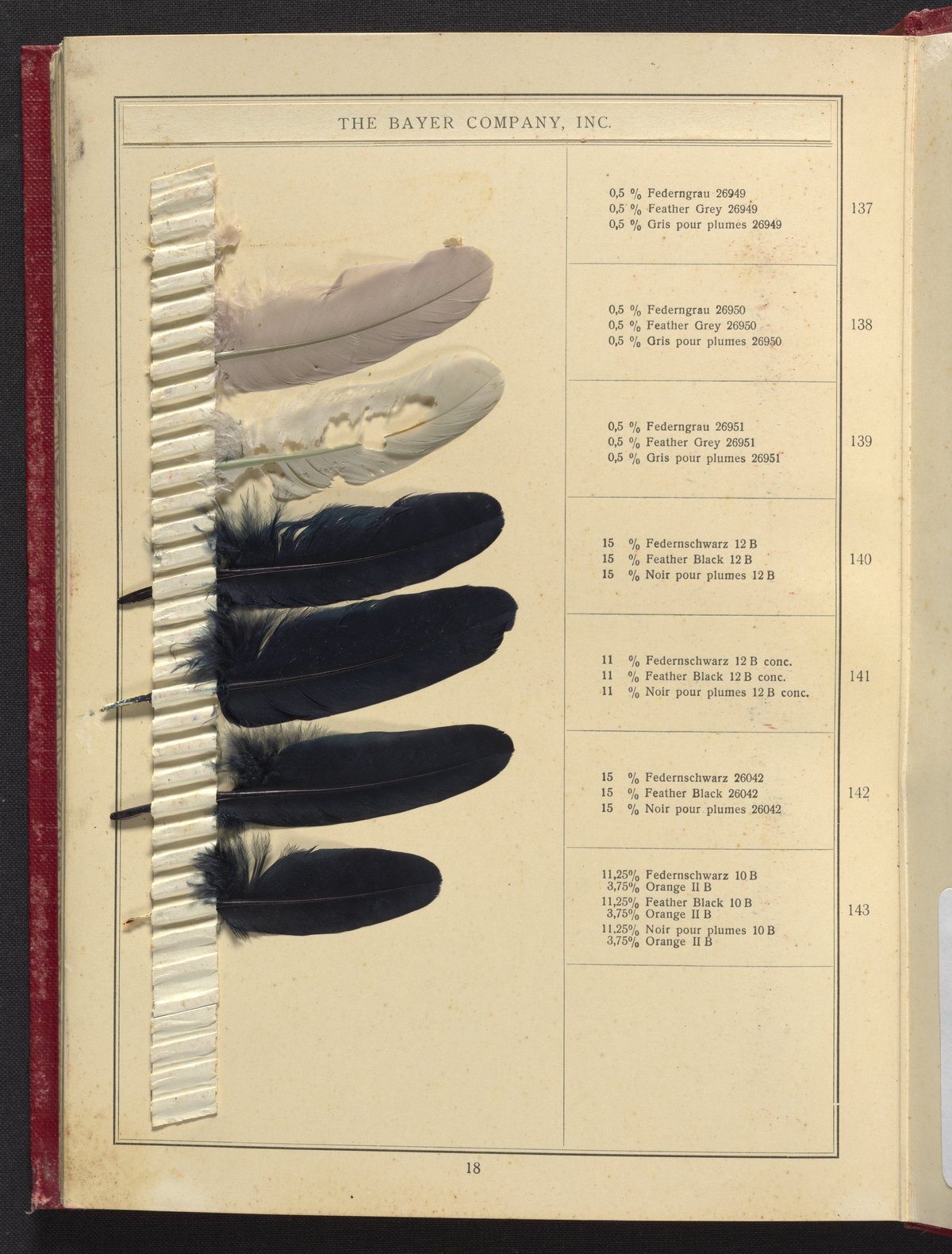

Ausfärbungen auf Federn / Teintures sur Plumes or Shades on Feathers is a sample book from 1915 with dyeing instructions and an 18-section foldout containing 143 dyed feathers. Published by the Bayer Company of New York City in English, French

and German, the book begins with instructions for dying feathers (clean them in soap and ammonia, then boil in salts and sulphuric acid).

Recipe 101 is as follows:

“Cold Dyeing for Purple which is Done in the True Way”

“Keep this as a secret matter because the purple has an extremely luster. Take scrum of woad from the dyer, and a sufficient portion of foreign askant of about the same weight as the scum – the scum is very light – and triturate it in the mortar. Thus dissolve the alkanet by grinding in the scum and it will give off its essence. Then take the brilliant color prepared by the dyer – if from kermis it is better, or else from kirmnos – heat, and put this liquor into half of the scum in the mortar. Then put the wool in and color it unmordanted and you will find it beyond all description.”

The most well-known shellfish dye was the Tyrian purple, royal purple or imperial purple as it was called, which came from sea snails in the Eastern Mediterranean in the ancient city of Tyre. This dye was very special for all the civilisations around the Mediterranean and its use spanned whole centuries. It was the most expensive dye in the whole of ancient world, as the colour it produced was very bright and colourfast. Because of its properties, its use was restricted for royals, members of the royal family, and senior public officers and priests.

Archaeological evidence points out that the ancient Phoenicians first discovered and used it (Tyre was an important Phoenician city). From them, it became known to ancient Greeks, Romans and through them in Byzantium and Medieval Europe. It was so sought after that the Byzantine emperor Theodosius I prohibited its use from the lower classes or the penalty was death. The privilege of using this purple dye is so profound that the phrase “born in purple” was born in that period. In Western Europe, it was replaced in prominence around the 12th century, and finally went out of fashion around the 19th century, when a synthetic purple was invented and thus it became more accessible to the wider masses.

All that changed in mid 19th century, with the invention of synthetic dye. Dyed garments became more affordable, which coincides with the Industrial Revolution and the rise of the middle class.

And we have a German teenager to thank. In 1856, William Henry Perkin was searching for a cure for malaria when he discovered the first synthetic dye. Mauve in colour, this aniline dye would be the beginning of a new era in the history of fabric dying.

The Science Museum Group notes:

Perkin named the colour mauve and the dye mauveine. He decided to try to market his discovery instead of returning to college.

On 26 August 1856, the Patent Office granted Perkin a patent for ‘a new colouring matter for dyeing with a lilac or purple colour stuffs of silk, cotton, wool, or other materials’.

Perkin’s next step was to interest cloth dyers and printers in his discovery. He had no experience of the textile trade and little knowledge of large-scale chemical manufacture. He corresponded with Robert and John Pullar in Glasgow, who offered him support. Perkin’s luck changed towards the end of 1857 when the Empress Eugénie, wife of Napoleon III, decided that mauve was the colour to wear. In January 1858, Queen Victoria followed suit, wearing mauve to her daughter’s wedding.

Via: Science History Institute

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.