Karl Marx wrote three albums of poems in the late autumn of 1836 and in the winter of 1836-37.

According to his daughter Laura Lafargue and his biographer Franz Mehring, who had access to his manuscripts after his death, two of these albumn bore the title Book of Love, Part I and Part II, and the third, Book of Songs. Each had the following dedication:

“To my dear, ever beloved Jenny von Westphalen.”

The covers of the albums were later included by Marx in his book of verse dedicated to his father.

Did Karl enjoy his ode to love? Laura Lafargue noted:

“My father treated his verses very disrepectfully; whenever my parents mentioned them, they would laugh to their heart’ content.”

With titles like “Yearning,” “Siren Song”, “Two Singers Accompanying Themselves on the Harp” and “Harmony” we can smirk.

From the BOOK OF LOVE (Part I) [2]

CONCLUDING SONNETS TO JENNY

I

Take all, take all these songs from me

That Love at your feet humbly lays,

Where, in the Lyre’s full melody,

Soul freely nears in shining rays.

Oh! if Song’s echo potent be

To stir to longing with sweet lays,

To make the pulse throb passionately

That your proud heart sublimely sways,

Then shall I witness from afar

How Victory bears you light along,

Then shall I fight, more bold by far,

Then shall my music soar the higher;

Transformed, more free shall ring my song,

And in sweet woe shall weep my Lyre.

II

To me, no Fame terrestrial

That travels far through land and nation

To hold them thrillingly in thrall

With its far-flung reverberation

Is worth your eyes, when shining full,

Your heart, when warm with exultation,

Or two deep-welling tears that fall,

Wrung from your eyes by song’s emotion.

Gladly I’d breathe my Soul away

In the Lyre’s deep melodious sighs,

And would a very Master die,

Could I the exalted goal attain,

Could I but win the fairest prize —

To soothe in you both joy and pain.

III

Ah! Now these pages forth may fly,

Approach you, trembling, once again,

My spirits lowered utterly

By foolish fears and parting’s pain.

My self-deluding fancies stray

Along the boldest paths in vain;

I cannot win what is most High,

And soon no more hope shall remain.

When I return from distant places

To that dear home, filled with desire,

A spouse holds you in his embraces,

And clasps you proudly, Fairest One.

Then o’er me rolls the lightning’s fire

Of misery and oblivion.

IV

Forgive that, boldly risking scorn

The Soul’s deep yearning to confess,

The singer’s lips must hotly burn

To waft the flames of his distress.

Can I against myself then turn

And lose myself, dumb, comfortless,

The very name of singer spurn,

Not love you, having seen your face?

So high the Soul’s illusions aspire,

O’er me you stand magnificent;

‘Tis but your tears that I desire,

And that my songs you only enjoyed

To lend them grace and ornament;

Then may they flee into the Void!

*

From the BOOK OF SONGS [3]

TO JENNY

I

Words — lies, hollow shadows, nothing more,

Growding Life from all sides round!

In you, dead and tired, must I outpour

Spirits that in me abound?

Yet Earth’s envious Gods have scanned before

Human fire with gaze profound;

And forever must the Earthling poor

Mate his bosom’s glow with sound.

For, if passion leaped up, vibrant, bold,

In the Soul’s sweet radiance,

Daringly it would your worlds enfold,

Would dethrone you, would bring you down low,

Would outsoar the Zephyr-dance.

Ripe a world above you then would grow.

TO JENNY

I

Jenny! Teasingly you may inquire

Why my songs “To Jenny” I address,

When for you alone my pulse beats higher,

When my songs for you alone despair,

When you only can their heart inspire,

When your name each syllable must confess,

When you lend each note melodiousness,

When no breath would stray from the Goddess?

‘Tis because so sweet the dear name sounds,

And its cadence says so much to me,

And so full, so sonorous it resounds,

Like to vibrant Spirits in the distance,

Like the gold-stringed Cithern’s harmony,

Like some wondrous, magical existence.

II

See! I could a thousand volumes fill,

Writing only “Jenny” in each line,

Still they would a world of thought conceal,

Deed eternal and unchanging Will,

Verses sweet that yearning gently still,

All the glow and all the Aether’s shine,

Anguished sorrow’s pain and joy divine,

All of Life and Knowledge that is mine.

I can read it in the stars up younder,

From the Zephyr it comes back to me,

From the being of the wild waves’ thunder.

Truly, I would write it down as a refrain,

For the coming centuries to see —

LOVE IS JENNY, JENNY IS LOVE’S NAME.

The letters worked. Karl and Jenny 4 ever!

Edmund Wilson’s To the Finland Station: A Study in the Writing and Acting of History includes a segment on Karl Marx’s entreating Jenny von Westphalen, who would be his wife:

Next door to the Marxes in Trier lived a family named van Westphalen. Baron von Westphalen, though a Prussian official, was also a product of eighteenth-century civilization: his father had been confidential secretary to the liberal Duke Ferdinand of Brunswick, the friend of Winckelmann and Voltaire, and had been ennobled by him. Ludwig von Westphalen read seven languages, loved Shakespeare and knew Homer by heart. He used to take young Karl Marx for walks among the vineyard-covered hills of the Moselle and tell him about the Frenchman, Saint-Simon, who wanted society organized scientifically in the interests of Christian charity: Saint-Simon had made an impression on Herr von Westphalen. The Marxes had their international background of Holland, Poland and Italy and so back through the nations and the ages; Ludwig von Westphalen was half-German, half-Scotch; his mother was of the family of the Dukes of Argyle; he spoke German and English equally well. Both the Westphalens and the Marxes belonged to a small community of Protestant officials — numbering only a scant three hundred among a population of eleven thousand Catholics, and most of them transferred to Trier from other provinces — in that old city, once a stronghold of the Romans, then a bishopric of the Middle Ages, which during the lifetimes of the Westphalens and Marxes had been ruled alternately by the Germans and the French. Their children played together in the Westphalens’ large garden. Karl’s sister and Jenny von Westphalen became one another’s favorite friends. Then Karl fell in love with Jenny.

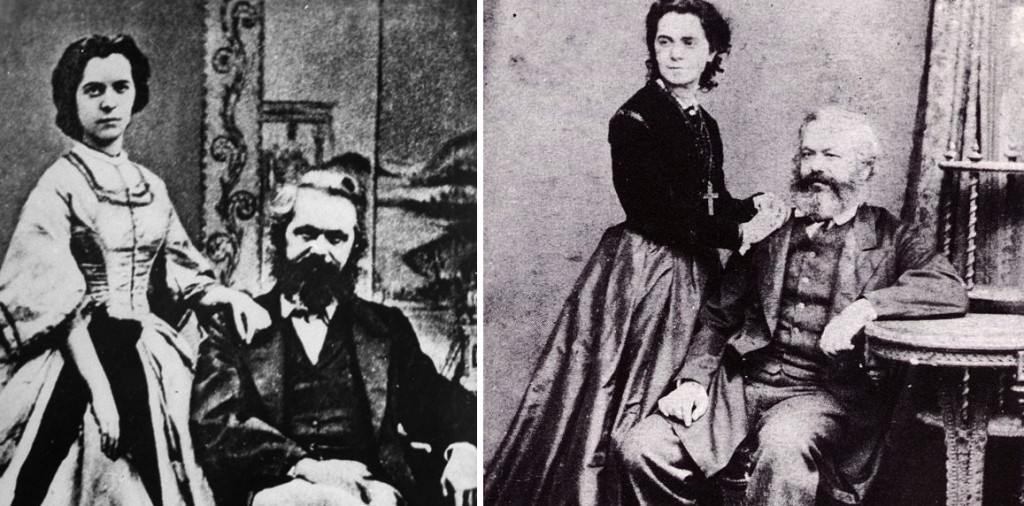

In the summer of Karl’s eighteenth year, when he was home on his vacation from college, Jenny von Westphalen promised to marry him. She was four years older than Karl and was considered one of the belles of Trier, was much courted by the sons of officials and landlords and army officers; but she waited for Karl seven years. She was intelligent, had character, talked well; had been trained by a remarkable father. Karl Marx had conceived for her a devotion which lasted through his whole life. He wrote her bad romantic poetry from college.

This early student poetry of Marx, which he himself denounced as rhetorical almost as soon as he had written it, is nevertheless not without its power, and it is of interest in presenting the whole repertoire of his characteristic impulses and emotions before they are harnessed to the pistons of his system.

As a final note, this is what Jenny Von Westphalen wrote to Karl Marx in 1839. Lckcking his rhymes, she laid bare her heart in dense pros:

My dear and only beloved,

Sweetheart, are you no longer angry with me, and also not worried about me? I was so very upset when I last wrote, and in such moments I see everything still much blacker and more terrible than it actually is. Forgive me, one and only beloved, for causing you such anxiety, but I was shattered by your doubt of my love and faithfulness. Tell me, Karl, how could you do that, how could you set it down so dryly in writing to me, express a suspicion merely because I was silent somewhat longer than usual, kept longer to myself the sorrow I felt over your letter, over Edgar, indeed over so much that filled my soul with unspeakable misery. I did it only to spare you, and to save myself from becoming upset, a consideration which I owe indeed to you and to my family.

Oh, Karl, how little you know me, how little you appreciate my position, and how little you feel where my grief lies, where my heart bleeds. A girl’s love is different from that of a man, it cannot but be different. A girl, of course, cannot give a man anything but love and herself and her person, just as she is, quite undivided and for ever. In ordinary circumstances, too, the girl must find her complete satisfaction in the man’s love, she must forget everything in love. But, Karl, think of my position, you have no regard for me, you do not trust me. And that I am not capable of retaining your present romantic youthful love, I have known from the beginning, and deeply felt, long before it was explained to me so coldly and wisely and reasonably. Oh, Karl, what makes me miserable is that what would fill any other girl with inexpressible delight — your beautiful, touching, passionate love, the indescribably beautiful things you say about it, the inspiring creations of your imagination — all this only causes me anxiety and often reduces me to despair. The more I were to surrender myself to happiness, the more frightful would my fate be if your ardent love were to cease and you became cold and withdrawn.

You see, Karl, concern over the permanence of your love robs me of all enjoyment. I cannot so fully rejoice at your love, because I no longer believe myself assured of it; nothing more terrible could happen to me than that. You see, Karl, that is why I am not so wholly thankful for, so wholly enchanted by your love, as it really deserves. That is why I often remind you of external matters, of life and reality, instead of clinging wholly, as you can do so well, to the world of love, to absorption in it and to a higher, dearer, spiritual unity with you, and in it forgetting everything else, finding solace and happiness in that alone. Karl, if you could only sense my misery you would be milder towards me and not see hideous prose and mediocrity everywhere, not perceive everywhere want of true love and depth of feeling.

Oh, Karl, if only I could rest safe in your love, my head would not burn so, my heart would not hurt and bleed so. If only I could rest safe for ever in your heart, Karl, God knows my soul would not think of life and cold prose. But, my angel, you have no regard for me, you do not trust me, and your love, for which I would sacrifice everything, everything, I cannot keep fresh and young. In that thought lies death; once you apprehend it in my soul, you will have greater consideration for me when I long for consolation that lies outside your love. I feel so completely how right you are in everything, but think also of my situation, my inclination to sad thoughts, just think properly over all that as it is, and you will no longer be so hard towards me. If only you could be a girl for a little while and, moreover, such a peculiar one as I am.

So, sweetheart, since your last letter I have tortured myself with the fear that for my sake you could become embroiled in a quarrel and then in a duel. Day and night I saw you wounded, bleeding and ill, and, Karl, to tell you the whole truth, I was not altogether unhappy in this thought: for I vividly imagined that you had lost your right hand, and, Karl, I was in a state of rapture, of bliss, because of that. You see, sweetheart, I thought that in that case I could really become quite indispensable to you, you would then always keep me with you and love me. I also thought that then I could write down all your dear, heavenly ideas and be really useful to you. All this I imagined so naturally and vividly that in my thoughts I continually heard your dear voice, your dear words poured down on me and I listened to every one of them and carefully preserved them for other people. You see, I am always picturing such things to myself, but then I am happy, for then I am with you, yours, wholly yours. If I could only believe that to be possible, I would be quite satisfied. Dear and only beloved, write to me soon and tell me that you are well and that you love me always.

But, dear Karl, I must once more talk to you a little seriously. Tell me, how could you doubt my faithfulness to you? Oh, Karl, to let you be eclipsed by someone else, not as if I failed to recognise the excellent qualities in other people and regarded you as unsurpassable, but, Karl, I love you indeed so inexpressibly, how could I find anything even at all worthy of love in someone else? Oh, dear Karl, I have never, never been wanting in any way towards you, yet all the same you do not trust me. But it is curious that precisely someone was mentioned to you who has hardly ever been seen in Trier, who cannot be known at all, whereas I have been often and much seen engaged in lively and cheerful conversation in society with all kinds of men. I can often be quite cheerful and teasing, I can often joke and carry on a lively conversation with absolute strangers, things that I cannot do with you. You see, Karl, I could chat and converse with anyone, but as soon as you merely look at me, I cannot say a word for nervousness, the blood stops flowing in my veins and my soul trembles.

Often when I thus suddenly think of you I am dumbstricken and overpowered with emotion so that not for anything in the world could I utter a word. Oh, I don’t know how it happens, but I get such a queer feeling when I think of you, and I don’t think of you on isolated and special occasions; no, my whole life and being are but one thought of you. Often things occur to me that you have said to me or asked me about, and then I am carried away by indescribably marvellous sensations. And, Karl, when you kissed me, and pressed me to you and held me fast, and I could no longer breathe for fear and trembling, and you looked at me so peculiarly, so softly, oh, sweetheart, you do not know the way you have often looked at me. If you only knew, dear Karl, what a peculiar feeling I have, I really cannot describe it to you I sometimes think to myself, too, how nice it will he when at last I am with you always and you call me your little wife. Surely, sweetheart, then I shall be able to tell you all that I think, then one would no longer feel so horribly shy as at present.

Dear Karl, it is so lovely to have such a sweetheart. If you only knew what it is like, you would not believe that I could ever love anyone else. You, dear sweetheart, certainly do not remember all the many things you have said to me, when I come to think of it. Once you said something so nice to me that one can only say when one is totally in love and thinks one’s beloved completely at one with oneself. You have often said something so lovely, dear Karl, do you remember? If I had to tell you exactly everything I have been thinking — and, my dear rogue, you certainly think I have told you everything already, but you are very much mistaken — when I am no longer your sweetheart, I shall tell you also what one only says when one belongs wholly to one’s beloved.

Surely, dear Karl, you will then also tell me everything and will again look at me so lovingly. That was the most beautiful thing in the world for me. Oh, my darling, how you looked at me the first time like that and then quickly looked away, and then looked at me again, and I did the same, until at last we looked at each other for quite a long time and very deeply, and could no longer look away. Dearest one, do not be angry with me any more and write to me also a little tenderly, I am so happy then. And do not be so much concerned about my health. I often imagine it to be worse than it is. I really do feel better now than for a long time past. I have also stopped taking medicine and my appetite, too, is again very good. I walk a lot in Wettendorfs garden and am quite industrious the whole day long. But, unfortunately, I can’t read anything. If I only knew of a book which I could understand properly and which could divert me a little. I often take an hour to read one page and still do not understand anything. To be sure, sweetheart, I can catch up again even if I get a little behind at present, you will help me to go forward again, and I am quick in grasping things too. Perhaps you know of some book, but it must be quite a special kind, a bit learned so that I do not understand everything, but still manage to understand something as if through a fog, a bit such as not everyone likes to read; and also no fairy-tales, and no poetry, I can’t bear it. I think it would do me a lot of good if I exercised my mind a bit. Working with one’s hands leaves too much scope to the mind. Dear Karl, only keep well for my sake. The funny little dear is already living somewhere else. I am very glad at the change in your….

Roses are Reds…

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.