What you need for your car is a mascot. And no mascot is more delightful, delicate and precious than a Lalique glass mascot.

1920: Rene Lalique ( 1860-1945 ), artist, decorator, and French glassworker. RV-25537 (Photo by Albin Guillot/Roger Viollet/Getty Images)

Created by René Claude Lalique (1860-1945) at his workshop in Wingen-sur-Moder, Alsace, these mascots are virtual pets that won’t scratch the paintwork or soil the upholstery.

Many of the creatures attached to the hoods of smarter cars offered the driver the experience of being on a hunt without the need for a horse. There you are sat in your wainscoted motorised cabin, looking forward at the angelic nude, perch or wild boar on the bonnet’s edge. For the royal classes, there was the added thrill of peeking at the quarry over the shoulder of a liveried yeoman at the wheel.

(Modern, less grand cars go for roadkill – flattened pictures of lions (Peugeot), Jaguars (Jaguar) and, most oddly, heraldic and largely mythical griffins (Vauxhall). All endangered species but not proud enough to stand on the bonnet, preferring to play dead).

October 1929: Mascots, intended for use on the bonnets of cars, on display at the Motor Show, at Olympia in London. (Photo by Fox Photos/Getty Images)

G.G. Weiner’s has compiled the Lalique mascots into the book Unique Lalique Mascots. He tells Collectors’ Weekly:

“I’d been dealing in automobilia like car badges and brochures for quite a number of years when I came across a Lalique mascot in an exhibition at the Retromobile show in Paris. I made a lot of inquiries and went to the Lalique showroom in Paris on Rue Royale. They said that the mascots from the 1920s through 1930s were virtually impossible to get hold of. That set me off on a quest to try and find some. I sold off all of the automobilia I had to concentrate solely on Lalique.”

Of the 30 mascots featured, two – mermaids Sirène and Naïade – were mantlepiece ornaments rejigged for cars in 1925.

1929: A winged bullet mascot on the bonnet of politician David Lloyd George’s car. (Photo by Fox Photos/Getty Images)

Ben Marks notes a factoid:

Not coincidentally, 1925 was also the year of the Paris Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratives et Industriels Modernes, from which we get the abbreviated term Art Deco.

28th April 1925: The Galeries Lafayette pavilion at the Exposition Internationale des Arts Decoratifs Industriels et Modernes. The exhibition later gave it’s name in abbreviated form to the Art Deco style. (Photo by Topical Press Agency/Getty Images)

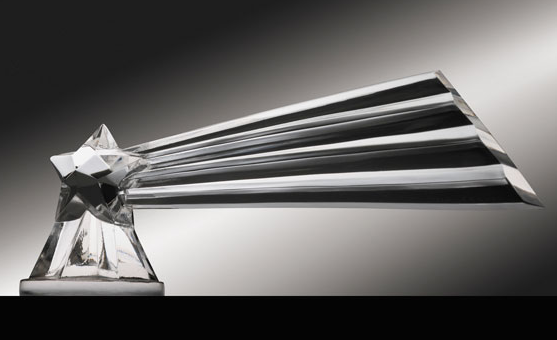

Lalique’s first three mascots were released in August of that year. One was the falcon, while another was inspired by the shooting stars on the side of the Eiffel Tower—the comets and their tails spelled out the word “Citröen” in what was then the largest illuminated advertisement in the world, so bright that aviator Charles Lindbergh used it as a beacon to guide the Spirit of St. Louis to Le Bourget Airport in 1927.

That mascot, the Comète Etoile Filante, was followed by another for the automaker, André Citröen, himself, whose new five-horsepower car, the 5CV, had just been introduced. Naturally, Lalique’s mascot for the 5CV resembled five horses in synchronized silhouette.

Cinq Chevaux (Five Horses, seen here on a Breves Galleries base) was made in 1925 for the new, five-horsepower Citröen 5CV.

Weiner considers their rarity:

“Most dealers and collectors will tell you that Renard, the Fox, is the rarest mascot, followed by Hibou, the Owl. The Lalique family says that only a handful of these were produced, but I’ve been to the Lalique factory in Alsace and have seen the steel molds made for the mascots. They’re very large and must have cost thousands and thousands of pounds to produce. You wouldn’t construct a mold like that just to make, say, a half-dozen mascots. You’d make at least 50, I would think. So when the family says Lalique produced only a handful, I simply don’t believe it. But even so, of 50 mascots made in, say, 1931, a lot were probably lost, broken, destroyed, or whatever. Are there 20, or possibly 30, left? Nobody really knows.”

In 2012, the New York Times spotted a full set of Lalique’s mascots for sale. They job lot went for $805,000. The newspaper adds more background:

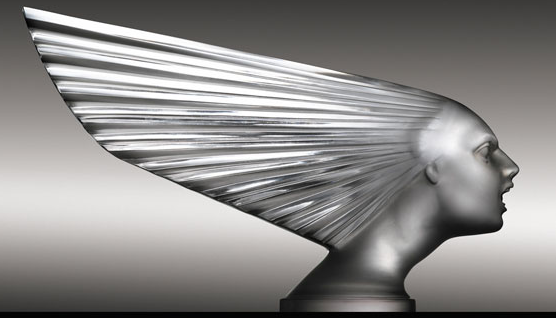

Small metal sculptures began to replace the thermometers and safety valves topping automobile radiators in the early days of the motorcar. The most famous of these, the Rolls-Royce Spirit of Ecstasy, also known as the Flying Lady, arrived in 1911.

The Rolls Royce mascot endures to this day. It soon became part of popular culture.

1929: Entertainer Elsa McFarlane stands on the bonnet of a Rolls Royce car, mimicking the Silver Lady figurine, in a production of ‘The Co-Optimists’, at the Vaudeville Theatre in London. (Photo by Sasha/Getty Images)

circa 1925: American film actress Corinne Griffith (1898 – 1979) as the ‘Spirit of Ecstasy’, the Rolls Royce emblem seen on the bonnet of their cars. (Photo by General Photographic Agency/Getty Images)

Well before manufacturers offered their own hood ornaments, affluent owners personalized the family car — Bentley or Bugatti, Hispano-Suiza or Isotta-Fraschini — with favorite designs, usually of metal.

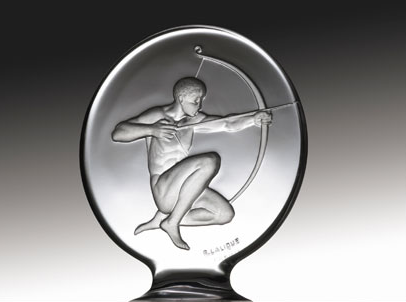

René Lalique was already a famous jeweler when he began to shrewdly court wealthy automobile owners. In 1906 he created gift plates for the winners of the Targa Florio races. Soon he was adapting some of the imagery of his 250 perfume bottles and paperweights into mascots to sit above the radiator.

May 1929: A mascot of an arrow on the bonnet of a Bentley car. (Photo by Fred Morley/Fox Photos/Getty Images)

May 1929: A seaplane mascot of a on the bonnet of an MG car. (Photo by Fred Morley/Fox Photos/Getty Images)

Lalique’s decision around 1910 to focus on glass provided the foundation for his luxury empire. “Lalique was an immensely talented artist with an entrepreneurial bent,” said David McFadden, chief curator at the Museum of Arts and Design in New York. “He realized that by taking a mundane material like glass, and adding artistry, he could reach a wider audience.”

Top: Chrysis (Nude Female), mounted on the radiator base of a Rolls-Royce Silver Wraith. Above: Renard (Fox) is considered one of the rarest Lalique mascots of the inter-war years.

For style and grace the lalique mascot cannot be topped. For usefulness, however, another kind of glass pointer is just the ticket:

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.