Strange but true tales of three famous London restaurants, all of which still remain open to diners.

Quaglino’s

When Quaglino’s was re-opened in February 1993 by Sir Terence Conran it was reported that the re-build had cost him around £2.5 million. This all had to be paid for somehow and many of the reviews at the time noted the restaurant’s eye-watering prices and that at £7.50 even the ashtrays were for sale. Not that anyone took much notice and so many customers slipped them in their pockets and handbags that within ten years 25,000 of the iconic ashtrays had been “mislaid”.

Giovanni Quaglino, the restaurant’s founder

The restaurant was established by Giovanni Quaglino in 1929 at 16 Bury Street in St James’s and within a year or two it became one of the most fashionable places to eat in London. Not least because the Prince of Wales, the future King Edward VIII, often dined there.

The restaurant’s popularity continued during World War Two when Picture Post wrote in 1941 that: “You can dine in comfort at one of the wall tables. You can dance, in less comfort, up till midnight on the crowded floor.” In 1947 the financier George Soros was a waiter at Quaglino’s and ate almost nothing else but leftover profiteroles.

During the 1950s Quaglino’s was still popular with royalty and a table was permanently reserved for regular visits by Princess Margaret and other members of the Royal Family including even the Queen on one evening in 1956. A few years later in 1963 John Profumo and his wife made a public show of togetherness by dancing at Quaglino’s after the news first broke that the War minister had slept with Christine Keeler.

During the 1960s the famous restaurant started to lose its aura. But at the end of the decade Quaglino’s, now owned by Trust House Forte, had one last brush with show business glamour, albeit rather faded. At Chelsea Town Hall on 15 March 1969, and just three months before she died, the 46 year old Judy Garland married her fifth husband – a gay discotheque-manager called Mickey Deans. The reception was at Quaglino’s but although several hundred guests were invited only a few made it to the function. Even Garland’s daughter Liza Minnelli had called to say, ‘I can’t make it Mamma but I promise I’ll come to your next one!’ Glasses of champagne remained un-drunk and most of the wedding cake stayed uneaten. The three-tiered cake had been given to Garland six weeks previously at the end of her five-week Talk of the Town engagement. Unfortunately nobody remembered to take it out of the deep-freeze in time so it was almost impossible to cut and eat.

Judy Garland and Mickey Dean’s wedding cake at Quaglino’s

A young actor friend of Deans called Allan Warren was asked to be the wedding photographer and he later described the scene: ‘When I got to Quaglino’s, there was a small band playing, a huge amount of press and and a little group of people sitting in the opposite corner. One was Judy, the other Johnnie Ray (the best man) and a third was a girl beside them in a wheelchair, who was never introduced. I took a few snaps including some of Judy and Mickey dancing. Then Mickey told me to dance with Judy as there was nobody else apart from Johnnie. She seemed very frail and very skinny. When we waltzed I could feel the bones of her spine sticking out. She also seemed very dazed as if on drugs, her eyes glazed over and she seemed very uptight. We danced in time to a one-armed trumpet player playing Somewhere Over the Rainbow. Afterwards I left as had to get to do a play. Mickey never paid me of course!’

Forty-five years later at a cost of £3 million, ‘Quags’, as Patsy from Absolutely Fabulous called the restaurant, was again refurbished in 2014 by D & D London. Said to have had ‘more facelifts than an ageing movie star’, Quaglino’s is again offering dinner, music and dancing just as it did in its initial glamorous heyday in the 1930s.

Quo Vadis

At the beginning of 1928 Evelyn Laye, the beautiful star of the West End stage, found out that her husband the actor and comedian Sonnie Hale was having an affair with her fierce rival Jessie Matthews. Depressed and confused she began eating alone at a little Italian restaurant called Quo Vadis situated at 27 Dean Street in Soho. Night after night she asked the owner, Peppino Leoni to show her to a wall table for one. Years later Laye remembered these solo dining experiences and quoted in an appreciative epilogue to Leoni’s biography, ‘The best number for a dinner party is two – myself and a dam’ good head-waiter.’ By the mid-1930s Quo Vadis, not least because of Laye’s patronage, became one of the most celebrated restaurants in London.

Kenneth Alexander, Evelyn Laye in “One Heavenly Night” directed by George Fitzmaurice, 1931

Peppino Leoni had arrived from Italy during the summer of 1914 and soon became the manager of Gallina’s Rendezvous in Dean Street (where the Groucho Club is now) run by Peter Gallina. Later to become Gennaro’s Rendezvous. After the First World War, Leoni became the head waiter at the Savoy and within a few years started Quo Vadis. In the mid-1930s the popular restaurant expanded to three buildings in the street, including no. 28. Leoni once wrote that a workman decorating the new acquisition asked him what to do with a load of old junk he had found upstairs. ‘What kind of junk?’ Leoni asked. ‘Oh, mostly exercise books, full of scribblings in some foreign language…’ Later that day Leoni’s architect, Alistair MacDonald, son of Ramsay MacDonald, told him that Karl Marx had apparently lived in the attic. But by then it was too late and the rubbish had been taken to a wharf, compressed, loaded onto barges and dumped in the North Sea.

In the years leading up to the Second World War the food at the Quo Vadis was described by reviewers as ‘International’ or ‘Franco-Italian’ and would not be seen as authentic Italian food today. In 1938 the Wine and Food journalist Christopher Dilke described the food as often being a ‘surprise’. ‘The sole is served with bananas, the pigeon with pineapple’, he explained.

During the 1920s and 1930s Fascism was never too far from the surface in ‘Little Italy’, as Soho was often called at the time. The Italian fascists even had a headquarters – the first to be organised outside Italy – based in Noël Street. The restaurant Gennaro’s on Old Compton Street, round the corner from Quo Vadis, even had ‘Lasagne alla Mussolini’ on its Saturday evening menu.

Gennaro’s Rendezvous 1947 44 Dean Street

In June 1940 Italy declared war on Britain and Churchill ordered that all London’s Italian males between the ages of sixteen and seventy were to be rounded up and interned, telling the police to ‘collar the lot’. Peppino Leoni was no exception. At his interrogation he did himself no favours by stating, ‘The King is a Fascist, Mussolini is a Fascist, most of the Italian people are Fascists. I am a patriotic Italian. Therefore I am a Fascist.’ Leoni was impressed, however, that his tax return was sent without being forwarded direct to his internment camp. ‘That would have never have happened in Italy,’ he wrote.

After the war, Peppino Leoni arrived back at Dean Street to find his restaurant all but destroyed. After a lot of work the restaurant eventually became recognisable again and it became more popular than ever – famous for its elegant silver service, celebrity guests, and most of all the charming manners of its host.

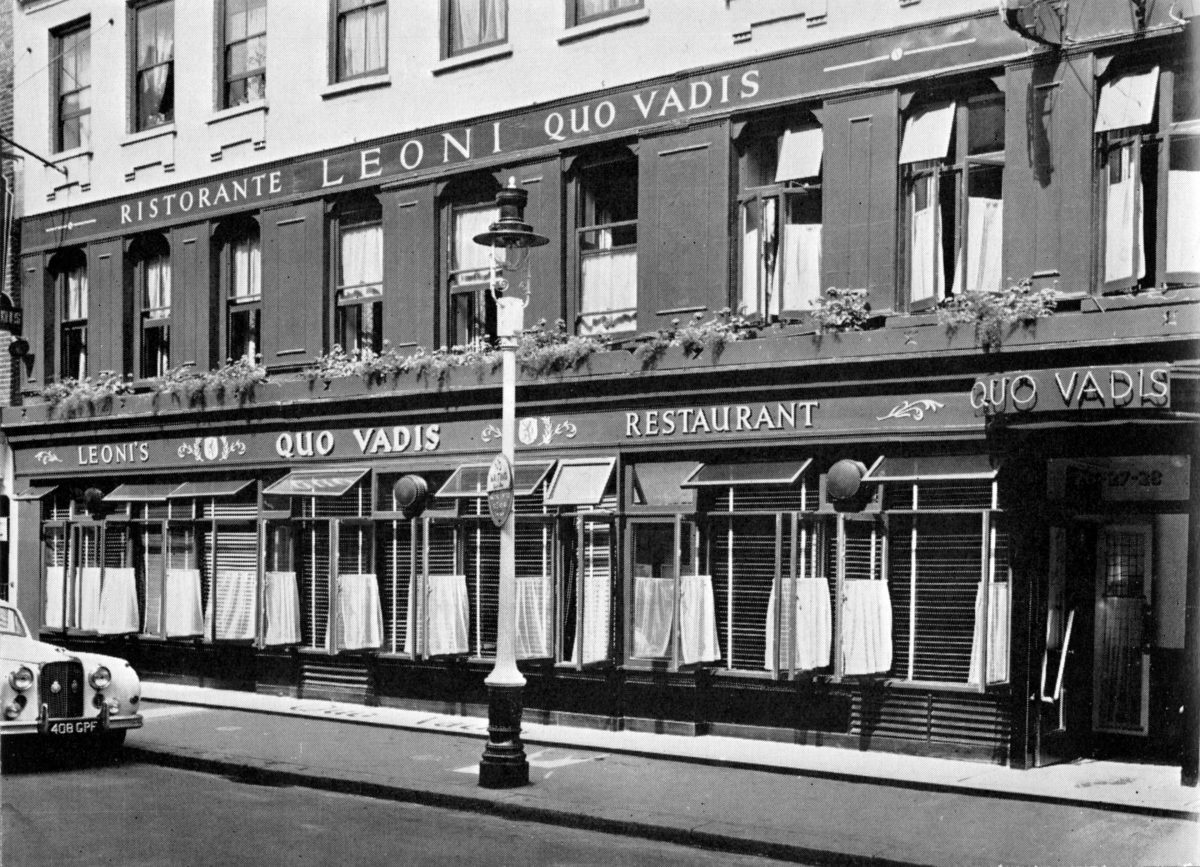

Quo Vadis c1965

Stanley Baker and Luciana Paluzzi at Quo Vadis 1958

Quo Vadis in 2017

As it has been for over ninety years, in one incarnation or other, Quo Vadis is still open for business at 26–29 Dean Street in Soho.

Scott’s

Scott’s Restaurant c.1950

During and after the war Fleming had a regular spot at the restaurant, a right-hand corner table for two on the first floor. It was also to be the favourite of his creation James Bond and it is said that it was at Scott’s that Fleming first heard the request for a Martini that was ‘shaken not stirred’. In Moonraker, Bond has a date to meet Gala Brand. He heads to Scott’s and waits:

Bond sat at his favourite restaurant table in London, the right-hand corner table for two on the first floor, and watched the people and traffic in Piccadilly and down the Haymarket.

In You Only Live Twice, Bond is happy to have finally got an assignment from M, and as he exits M’s office he has a request for Miss Moneypenny:

Be an angel, Penny and ring down to Mary and tell her she’s got to get out of whatever she’s doing tonight. I’m taking her out to dinner. Scott’s. Tell her we’ll have our first roast grouse of the year and pink champagne. Celebration.

In Diamonds Are Forever, Bond speaks to Bill Tanner, the Chief of Staff and Bond’s best friend in the service, and offers to take him out:

I’ll take you to Scott’s and we’ll have some of their dressed crab and a pint of black velvet …

Scott’s started in 1872 as an ‘oyster warehouse’ in the London Pavilion Music Hall. Because of its popularity, it expanded from 18 Coventry Street into both nos 19 and 20 before there was a major rebuilding in 1893 in the style of ‘Early French Renaissance’ by the designers Treadwell and Martin. Over the next fifty years Scott’s was always seen as one of the finest fish restaurants in London and was the traditional place for the more affluent Oxbridge undergraduates to eat and drink on Boat Race night.

The Brains Trust, 1955

Every Sunday from 1955 the four panellists, the question master, and the producer of The Brain’s Trust (initially a popular radio programme that began during the war, but which transferred to television in 1955) would meet at mid-day at Scott’s where ‘they’d eat a good lunch with a fair amount to drink’ before they were driven to the television studios at Lime Grove in time for a 4.15 p.m. start. Luminaries such as William Golding, John Betjeman, Rebecca West and Jacob Bronowski (described as ‘some of the finest intelligences in the country’ by the Radio Times in September 1958) were paid £50 a programme, particularly generous in those days, as this included a free lunch, drinks after the programme, and free transport home.

Scott’s was seen as a glamorous place to eat in the 1950s and 60s. Winston Churchill, Marilyn Monroe and Charlie Chaplin all visited, and the restaurant was mentioned in the 1963 film The Great Escape, when two POWs speak of Scott’s Bar in Piccadilly as the first place they wish to go when the war is over.

In 1967 the restaurant moved to Mount Street in Mayfair where, according to Kingsley Amis, the restaurant was ‘luxurious to the safe side of vulgarity’ and although he felt ‘conspicuous and flashy in his tweed jacket’ it was the sort of establishment where ‘nobody is noticeable except the ladies, and they only by their rarity’. Amis had anticipated the move of Scott’s restaurant in his James Bond continuation novel, Colonel Sun, where Bond is at Scott’s lunching on ‘Whitstable oysters, cold side of beef and potato salad, and a well-chilled bottle of Anjou rosé’ and fearing the worst: ‘

Bond had recently heard that the whole north side of (Coventry Street) was doomed to demolition,15 and counted every meal taken in those severe but comfortable panelled rooms a tiny victory over the new hateful London of steel and glass matchbox architecture.

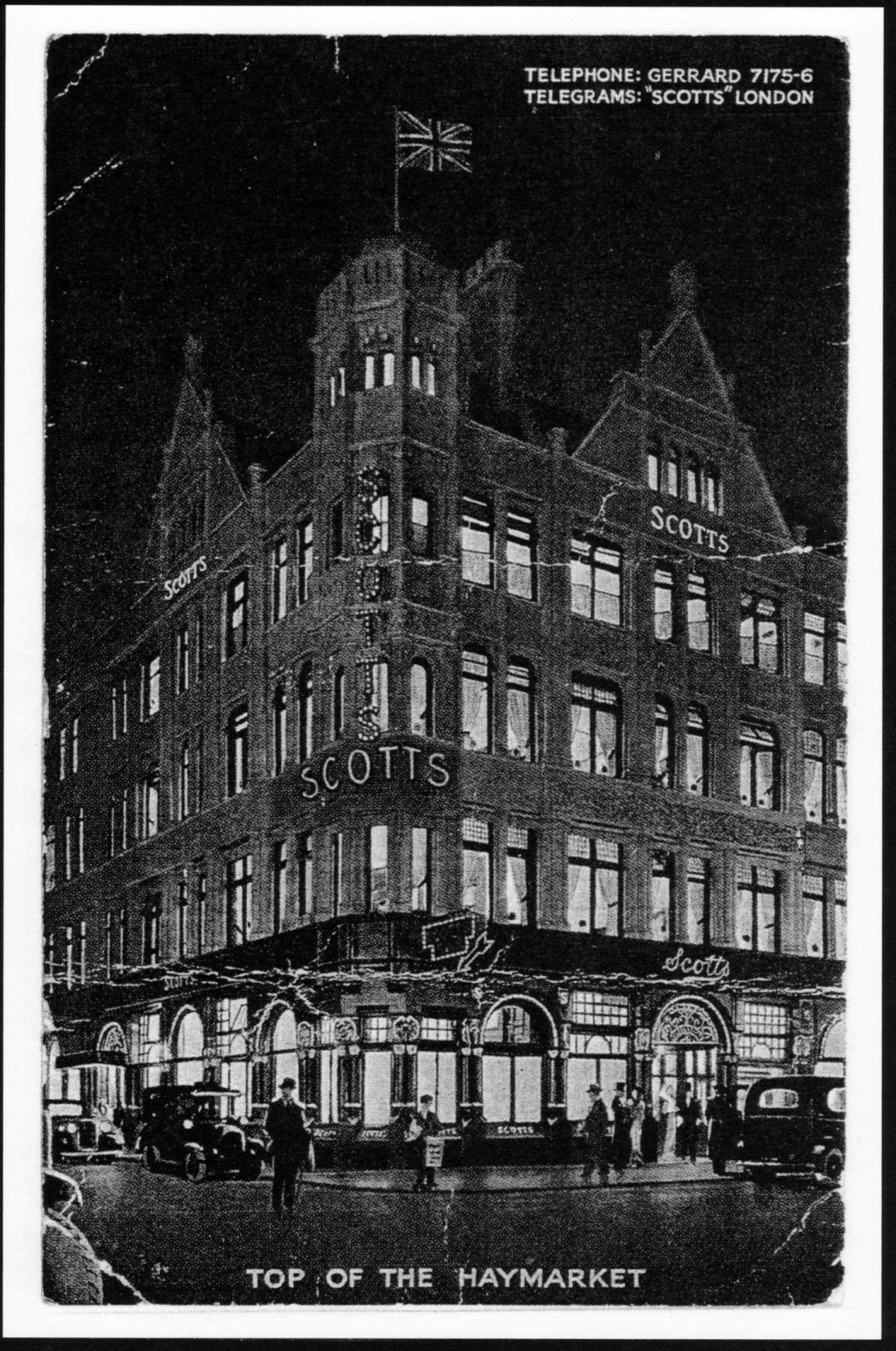

Postcard featuring Scott’s, c. 1930. The restaurant began life in 1872 when Charles Sonnhammer and Emil Loibl, the owners of the London Pavilion music hall, established an ‘oyster warehouse’ at 18 Coventry Street – although a ‘Scott’s oyster rooms’ existed on the Haymarket from at least 1853. In that year a Paul Shoreditch of Devereaux Court, Temple, was brought before a judge for trying to pass a forged £5 note at the establishment.

Coventry Street featuring Scott’s April 1956 Allan Hailstone

Surrounded by large classical French paintings and tarnished mirrors with fish and shellfish designs on the bar-panels and blinds, there were about seventy people dining in Scott’s Restaurant and Oyster Bar on the evening of 12 November 1975. The general chatter of the comfortably off while consuming oysters, crab and Chablis suddenly turned to screams when at 9.28 p.m. a large object came crashing through one of the two large round plate-glass windows. As soon as they heard the sound of breaking glass many of the customers feared the worst and threw themselves to the stone-clad floor. Seconds later the 5-pound shrapnel-laced gelignite throw bomb exploded.

It killed one man, John Batey, aged fifty-nine, and injured at least fifteen others, some very seriously. The explosion at Scott’s was caused by only one of the forty bombs that an IRA Active Service Unit (ASU) exploded in the capital in a fourteen-month campaign during 1974 and 1975. It was a campaign that some called ‘The Second Blitz of London’ and it left thirty-five people dead and many more seriously injured.

On 6 December 1975 the same gang stole a blue Ford Cortina but were spotted by a police officer driving unnaturally slowly down a road in Mayfair. The policeman, incredulously, then watched someone in the car open fire with a Sten gun at Scott’s – the same Mount Street restaurant that had been attacked less than four weeks earlier. The customers dived to the ground expecting the worst but this time they were in luck. The terrorist’s gun jammed and only two bullets were fired, causing no injuries or real damage. The IRA gang drove off but were followed by the police in a taxi. After a gun battle the gang holed up in a flat on Balcombe Street near Marylebone station where they took two hostages.

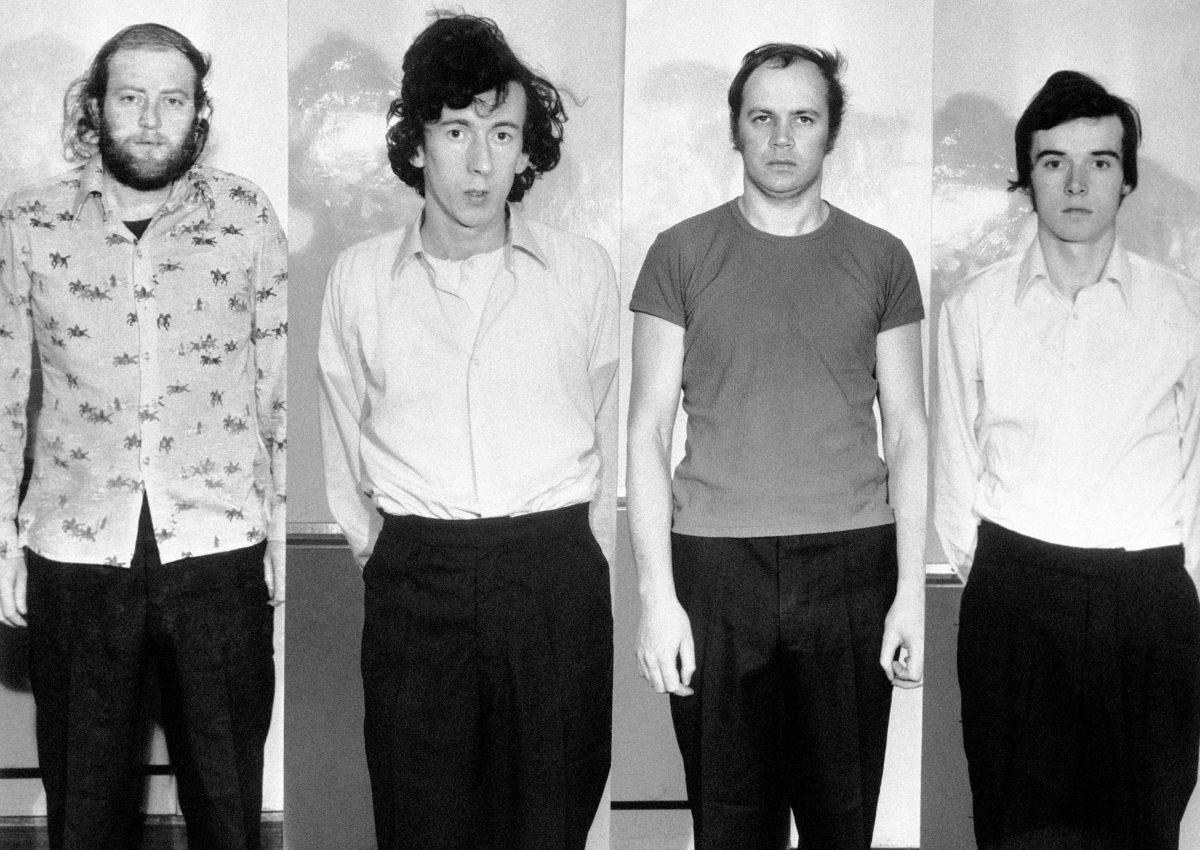

The four Provisional IRA terrorists known as the Balcombe Street Terror Gang, from left: Hugh Doherty, Martin O’Connel, Edward Butler and Harry Duggan, in a line up in London.

After six days the Balcombe Street gang, as they became to be known, gave themselves up. At the Old Bailey in 1977 they were convicted of eight killings (including that of Ross McWhirter of Guinesss Book of Records fame) and up to 50 bombings and shootings in public areas.

In 2005, Richard Caring bought Scott’s, which by then was looking tired and old-fashioned. After an extensive refurbishment it was reopened in November 2006 and again is now one of the best fish and seafood restaurants in London.

Scott’s Restaurant in Mount Street, 2017

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.