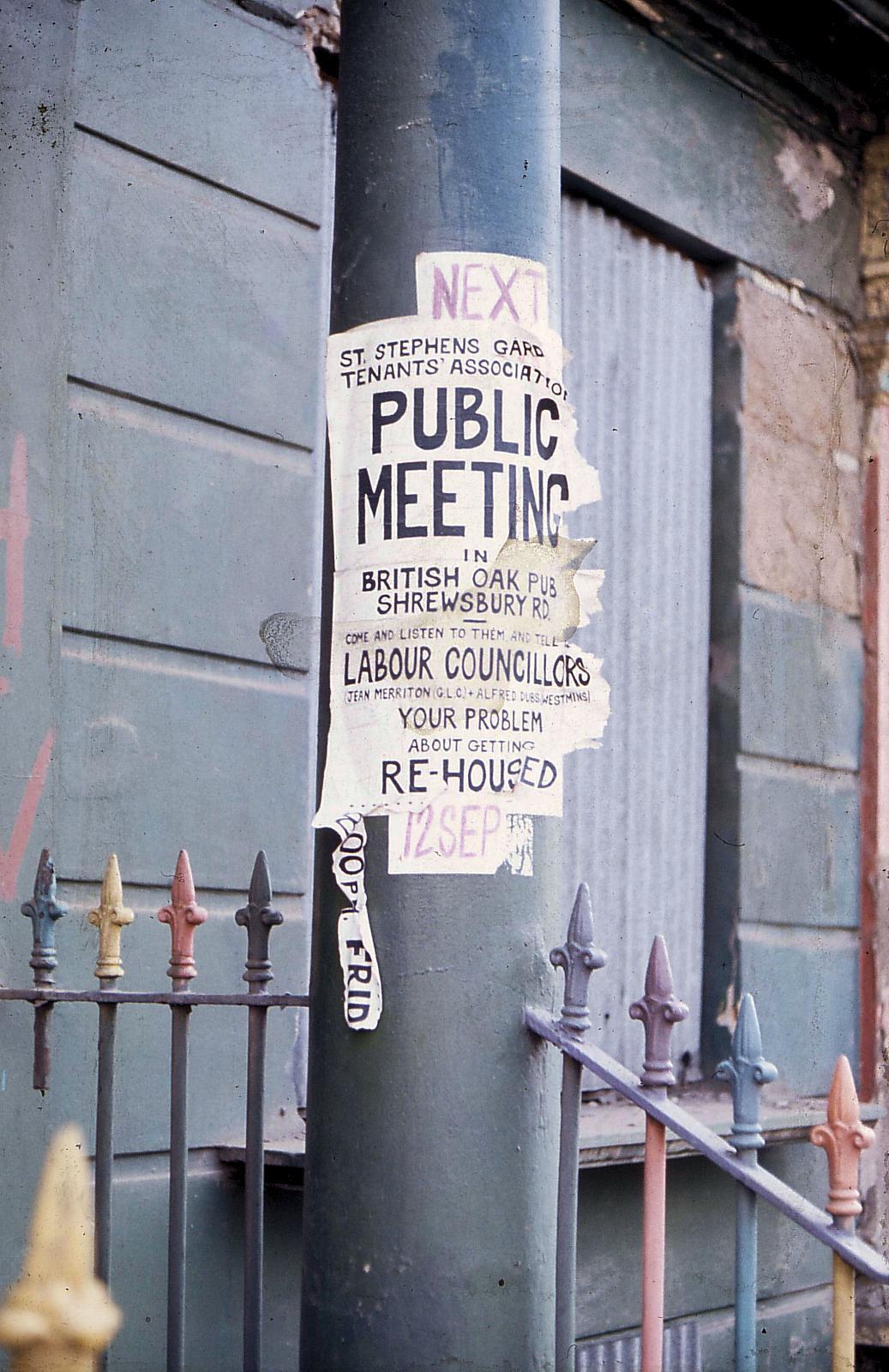

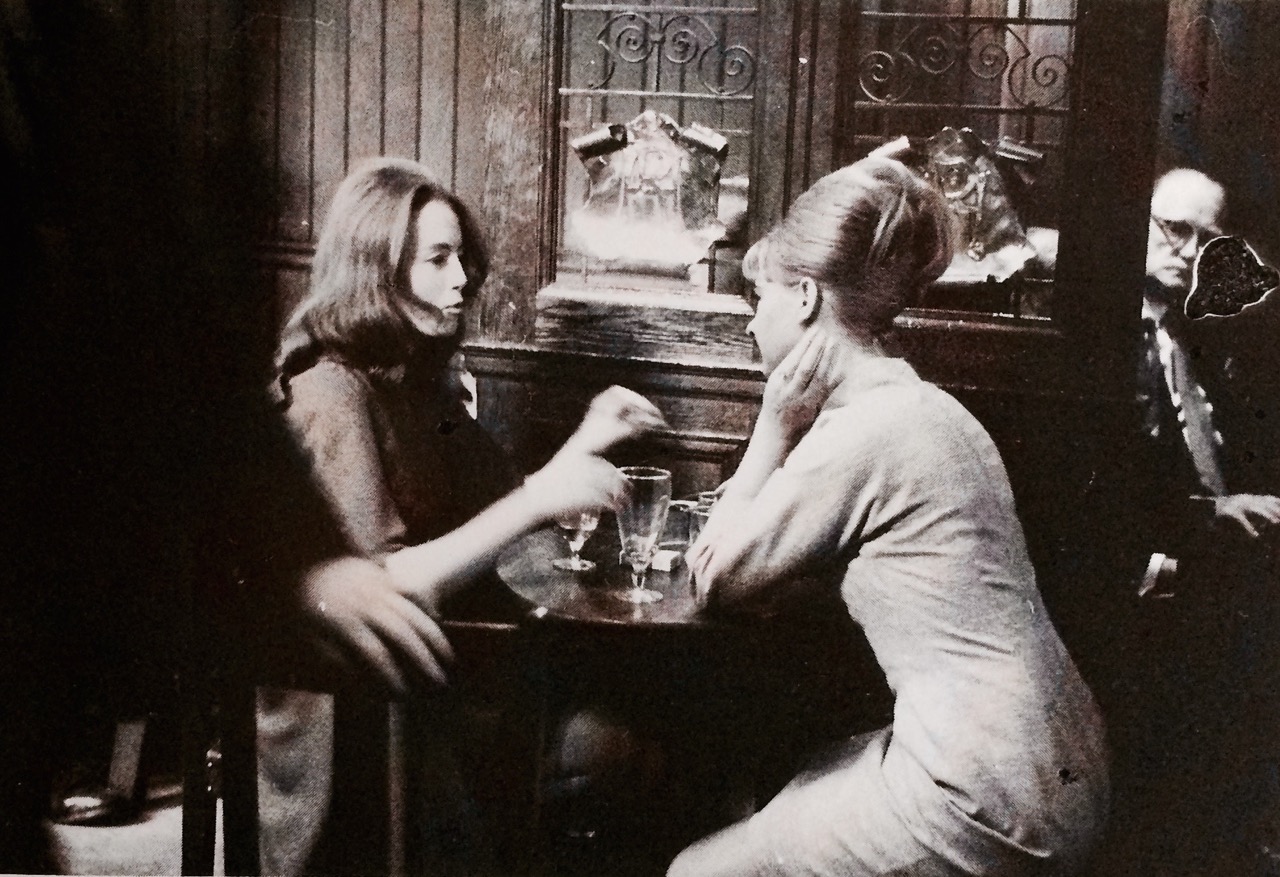

In a 1970 episode of the BBC sitcom Steptoe and Son called ‘Cuckoo in the Nest’, Harold leaves the family home after the unannounced arrival of Albert’s supposedly long lost Australian son. Harold moves to a particularly run-down bed-sit in a particularly run-down terrace of houses. The outside location chosen was St Stephen’s Gardens in West London – a street some of which was demolished a few years later as part of slum clearances of the time. Today a similar size bed-sit (now of course called a ‘studio apartment’) in what’s left of a now very fashionable St Stephen’s Gardens, will cost you somewhere in the vicinity of a million pounds. The decaying and run-down street had once been an early part of Peter Rachman’s property empire. In fact the first house he purchased and used for his infamous multi-occupation was in St Stephen’s Gardens.

It was the slow unfurling of the Profumo Affair in 1963 that rather belatedly brought the nefarious landlord Peter Rachman to the British public’s notice. He had actually died the previous year but his name was mentioned in court as someone who had kept both Christine Keeler and Mandy Rice-Davies as mistresses. Through sensational stories in the press, who had started looking into former life of the Polish emigré, it came to light the means to how Rachman had made his money. To this day his name is synonymous with exploitative and unscrupulous private landlords.

Born Perec Rachman in Poland (although now in Ukraine) in 1919 to a jewish dentist he was interned by the Nazis soon after their invasion in September 1939. After escaping to the Soviet Union he was cruelly treated in Stalin’s Siberian labour camps. He was so hungry at one point he was forced to eat human excrement although he once boasted: “I never ate German shit!” After Hitler declared war on the Soviet Union in 1941, Rachman and other Polish prisoners joined the 2nd Polish Corps and fought on behalf of the Allies in the Middle East and Italy. After the war he stayed with his unit, which remained as an occupying force in Italy until 1946, until they were brought to Britain.

Rachman was eventually demobilized in 1948 and became a British resident although, much to his annoyance, he was always refused citizenship. His business dealings started modestly while working for a Jewish tailor in Wardour Street and subsequently as a scorer at Jack Solomon’s billiard hall in Great Windmill Street. His property dealings began when he started finding rooms for prostitutes which led to him to help the Messina brothers’ vice syndicate in the role of “investment consultant”. By 1954, initially using a Bayswater Road phone-box as an ‘office’, Rachman built up a portfolio of houses, rented through his Express Lettings Agency in Notting Hill.

In the mid to late 1950s Rachman found rooms for West Indian tenants who otherwise were finding it difficult to obtain accommodation – although he charged extortionate rates for the privilege. By the end of the 1950s Rachman was making around £80,000 a year, not an inconsiderable sum in those days, although much of it was kept under his mattress. His letting business, and others like it, benefited hugely from a property boom that had followed the Conservative government’s relaxation of Abercrombie’s planning restrictions but also the 1957 Rent Act which enabled landlords to ‘de-control’ tenancies and increase rents.

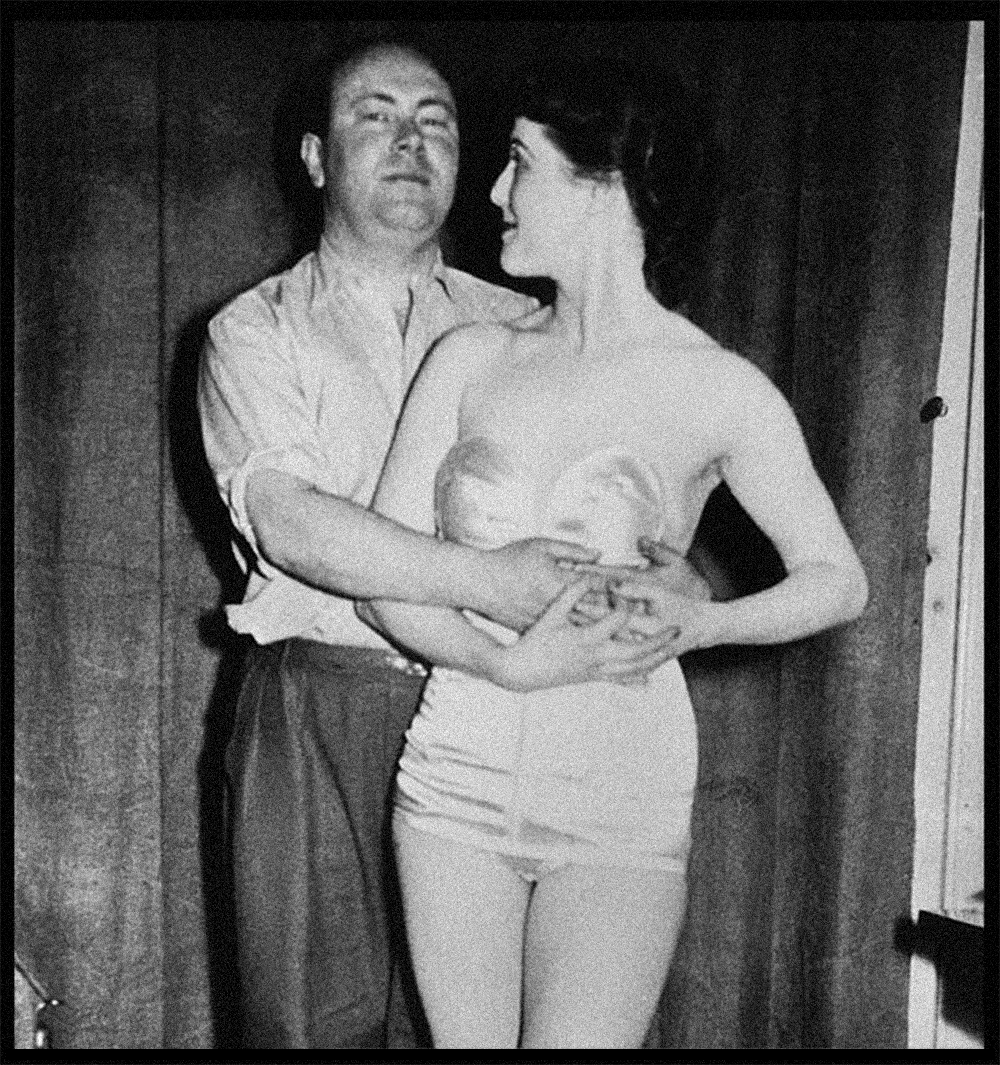

Rachman enjoyed his wealth and spent a lot on cars and women. He had affairs with both Christine Keeler (“sex to Rachman was like cleaning his teach and I was his toothbrush”) and Mandy Rice Davies who at sixteen became his permanent girlfriend (of sorts) for almost two years. It was said that Rice-Davies fainted when she heard of Rachman’s early death from a massive heart-attack in 1962, but not before saying ‘Did he leave a will?”. She once recalled, “His obsession with not letting the right hand know what the left hand was doing eventually worked against him. So great was the confusion over what property he owned that several business associated were able to claim ownership of houses, knowing there was nothing win paper to prove the contrary.” A gold bracelet engraved with serial numbers was found on the dead man’s wrist, however, and many thought that Rachman’s real fortune was stashed away in Swiss bank accounts, never to be found.

The timing of his death, six months before the Profumo Affair erupted meant that the press, unhindered by any libel laws, safely went to town about Rachman’s intimidation of tenants in his squalid run-down properties. The Sunday People exposed an ‘empire based on vice and drugs, violence and blackmail, extortion and slum landlordism the like of which this country has never seen and let us hope never will again’. In reality, most first hand accounts of the time said he was almost certainly not the worst of the landlords.

Resident and historian of the area Tom Vague in his fascinating book Getting it Straight in Notting Hill Gate tells of how the Sunday newspaper Empire News wrote that Rachman was: ‘probably London’s largest individual landlord for the coloured people… he doesn’t advertise vacant rooms or flats, the coloured people tell each other, “Go see Rachman, man.”’ Summing up the situation and himself, Rachman told the paper: “I find coloured people good tenants. I take people as they come. Mind you, some white people do object to the coloured people when they move in. They don’t like the way they play jazz records up to 1am, and always loudly. So when they come to me and say they are unhappy, I help them to find another house. I give them financial assistance. Last year I gave away £2,000 to help white tenants buy their own homes”. He created a ‘slum empire’ although, rather oddly, most people who had actually met him described him as generous, humorous and rather pleasant to be with.

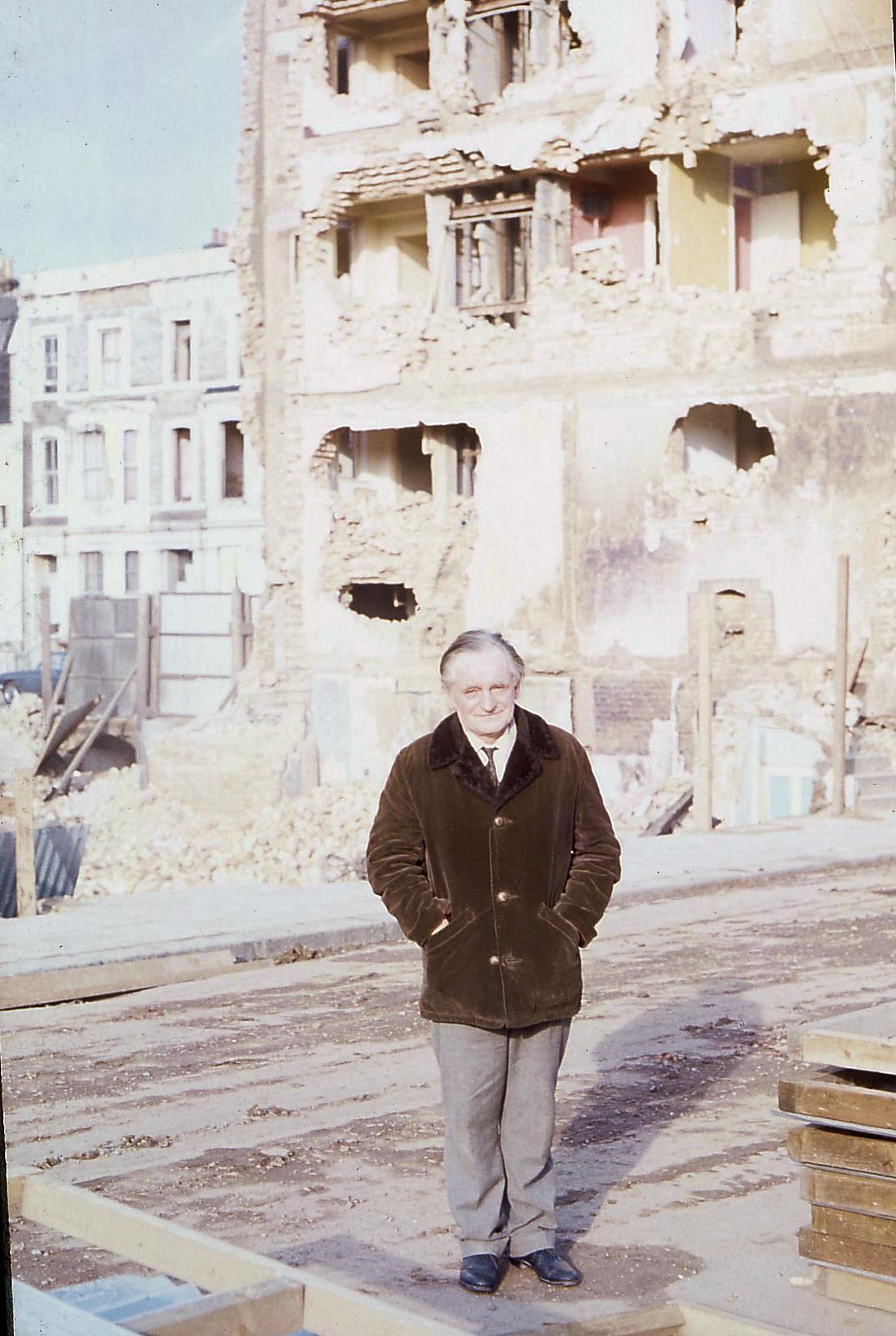

After his his initial purchases of houses in St Stephen’s Gardens Rachman bought into adjacent areas in Notting Hill (W11), including Powis Square, Powis Gardens, Powis Terrace, Colville Road and Colville Terrace where he also subdivided large properties into flats and let rooms, initially often for prostitution. Much of this area, south of Westbourne Park Road, having become derelict, was compulsorily purchased by Westminster City Council in the late 1960s and was demolished in 1973–75 to make way for the Wessex Gardens estate.

These photographs of this area, months before much of it was demolished, were taken in the winter of 1974 by Jonathan Barker. More of his fabulous photographs can be found at his flickr site.

Paddington: redevelopment at Westbourne Park, Feb 1974 This was a relatively new concrete block of flats on the northern corner of St Stephen’s Gardens & Moorhouse Rd

Feb 74: St Stephen’s Gardens looking E to Moorhouse Rd. All this soon came down view from Ledbury Road, Westbourne Park.

Demolition, houses in Westbourne Park Road, Paddington Feb 74 Backs of houses at corner of Ledbury & Wesbourne Park roads

Demolition of St Stephen’s Gardens, Moorhouse Rd & Gt Western Rd looking towards Keyham House tower to NW

Aftermath of Rachmanism in Paddington, Feb 1974: St Stephens Crescent, a street that survived demolition

a past resident and a building that took more forceful demolition than most: corner of Moorhouse Rd & St Stephen’s Gardens, Feb 1974

These photographs of a run-down Westbourne Park were taken in the winter of 1974 by Jonathan Barker and more of his fabulous photographs can be found at his flickr site.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.