“I call myself an illustrator but I am not an illustrator. Instead I paint story-telling pictures which are quite popular but unfashionable”

– Norman Rockwell

Norman Rockwell (February 3, 1894 – November 8, 1978) was an American painter and illustrator. In 2012, people who’d posed for paintings by this most American of artists, whose covers for the Saturday Evening Post seemed to represent the cosy immediacy of life in the USA, were photographed alongside them.

In the paintings, we see what Rockwell sees. What we don’t see can be every bit as revealing. And we saw a lot of Rockwell – 317 covers Post covers, each sent to the publication’s four million subscribers. The Post played a key role in shaping the way people felt about their country before TV killed it. Rockwell’s pictures had power, reinforcing ideals and in the Second World War reminding Americans what they were fighting for.

“Years ago,” Rockwell recalled “a magazine editor told me never to paint Negroes in any position except servants.” Black faces did appear in his work and in magazines the 1960s, as vociferous campaigning for civil right forced America to examine its conscience. His work Freedom’s Legacy for Look magazine shows Ruby Bridges, a black girl integrating a white New Orleans school. Murder in Mississippi illustrates of the deaths of civil rights activists James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner at the hands of the KKK. Rockwell’s pre-war cheery, harmonious escapism was not everyone’s America.

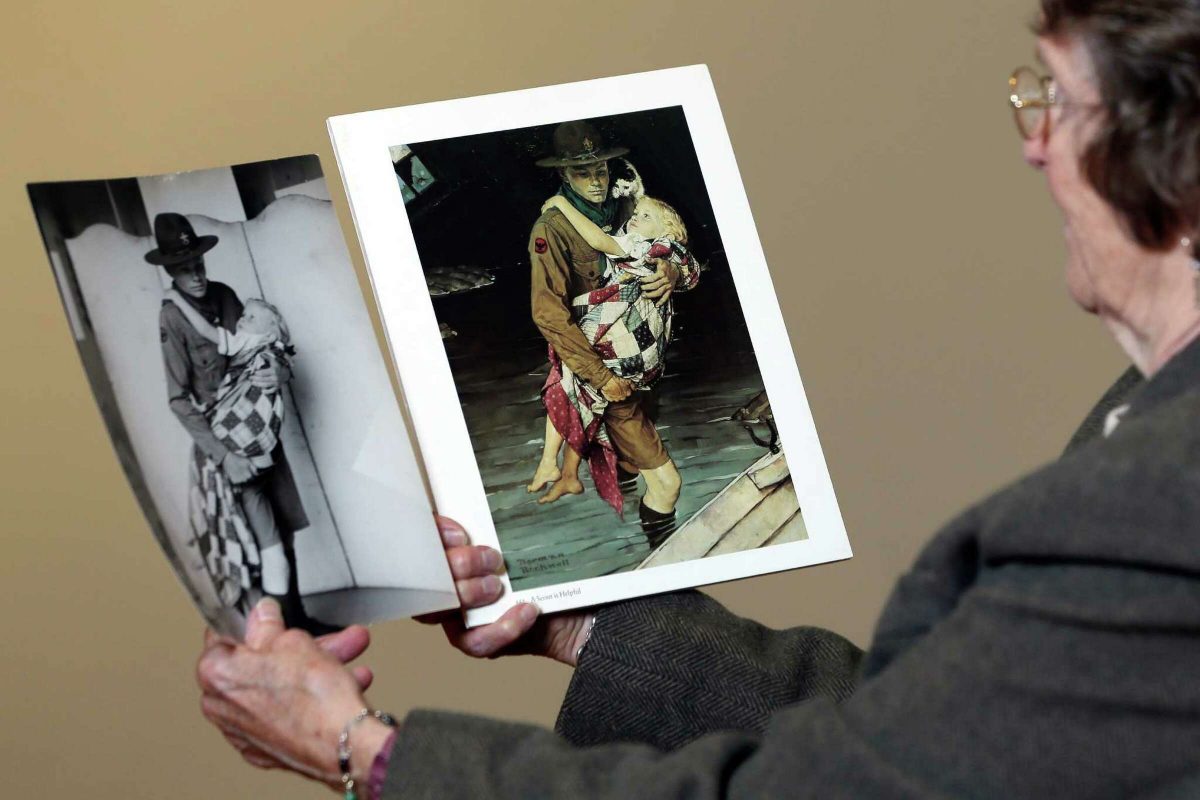

Mary Immen Hall of Bennington, Vt., poses with the 1940 Norman Rockwell illustration “A Scout is Helpful”

The creative process for such a prolific artist was routine. Rockwell would often begin with a photograph of an idea. Once the photograph was made, Rockwell used tracing and painting make his picture. He never painted freehand, and most of his paintings were commissioned by magazines and advertising agencies.

Writing in 1957, critic Wright Morris summed up Rockwell’s appeal:

He has taught a generation of Americans to see. They look about them and see, almost everywhere they look, what Norman Rockwell sees. The tomboy with the black eye, in the doctor’s waiting room; the father discussing the Facts of Life with his teen-age son; the youth in the dining car on his first solo flight from home; and the family in the car, headed for an outing, followed by the same family on the tired ride home.

The convincing realism of the details, photographic in their accuracy, is all subtly processed through a filter of sentiment. It is this sentiment that heightens the reality, making it for some an object of affection, for others — a small minority — an object of ridicule. It all depends on that intangible thing: the point of view.

Butch Corbett of Bennington, Vt., poses with a1950 Saturday Evening Post cover illustration “The Toss” by Norman Rockwell

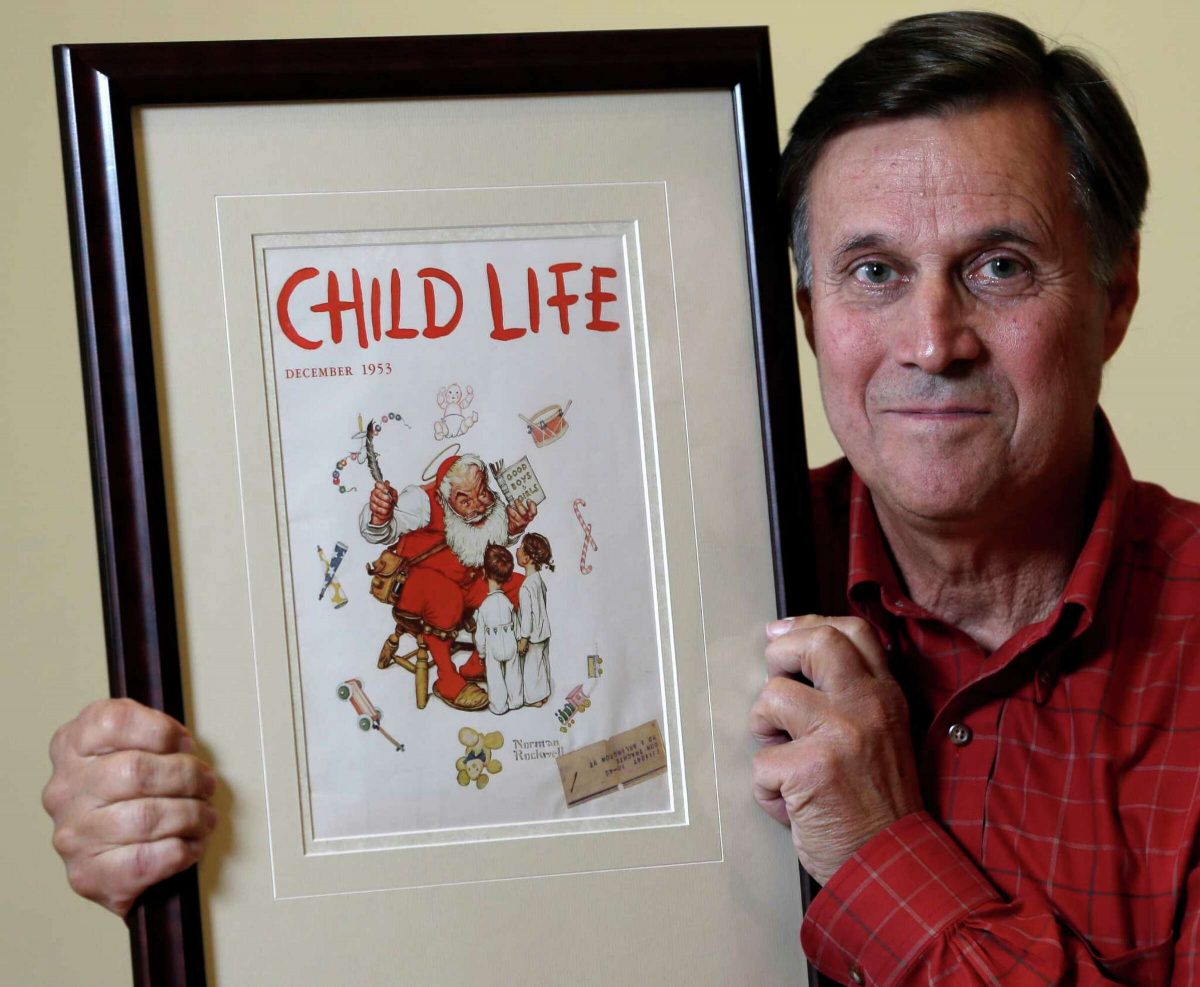

Don Trachte of Bennington, Vt., poses with a1953 Child Life magazine cover illustration “Santa’s Helpers” by Norman Rockwell

The above pictures formed an exhibition at the Bennington Museum on Friday, Sept. 28, 2012, in Bennington, Vt. The image below did not. We see Mary Doyle Keefe, model for Norman Rockwell’s Rosie the Riveter, for a 29 May 1943 issue of the Post.

Keefe grew up in Arlington, Vermont, where she met Rockwell, who lived in West Arlington. She posed for his painting when she was a 19-year-old telephone operator, earning $5 for each of two mornings she sat for Rockwell. “You sit there and he takes all these pictures,” Keefe told the Associated Press in 2002. “They [Rockwwll and photographer Gene Pelham] called me again to come back because he wanted me in a blue shirt and asked if I could wear penny loafers.”

Mary Doyle Keefe flexes next to a framed cover of the 1943 issue of the Saturday Evening Post that featured Norman Rockwell’s Rosie the Riveter. Photograph: Jim Cole/AP

This is a November 1973 photo of famed American painter Norman Rockwell at work in his studio in Chattanooga, TN

Lead image: Above, we see Tom Paquin of North Bennington, Vt., posing with a 1950 Saturday Evening Post illustration by Norman Rockwell for which he modelled.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.