The Allegory of Good and Bad Government is a series of three fresco panels painted by Ambrogio Lorenzetti (c. 1290 – 9 June 1348) in the Sala dei Nove in Siena’s town hall. The Council of Nine met in the this room. It is ‘one of the most revolutionary painting cycles of the 14th century’.

Douglas Blanchard explains:

Ambrogio Lorenzetti, one of two brothers (the other was Pietro), both brilliant artists and fierce competitors, painted a fresco cycle that covers three of four walls of the room. It is a very different subject from Simone’s Maesta. Instead of religious admonitions to the city’s leaders, Ambrogio paints a secular political allegory, perhaps the first such since ancient times. It is the Allegory of Good and Bad Government. The Allegory of Good Government takes up the whole wall at one end opposite the windows. The Effects of Good Government fill one of the long walls of the room to the right of Good Government. Bad Government and its effects take up the opposite left wall, which is always (significantly) in shadow. The cycle certainly admonishes the governors who met in this room, but it also argues for the success of republican government, by no means a settled issue at this time. Siena was not a democracy. As in Florence, an oligarchy of rich and powerful banking families held all the reigns of power in Siena. However, Ambrogio’s painting, like the writings of later Florentine political humanists such as Coluccio Salutati, Nicola da Uzzano, and Lionardo Bruni, argues for the success of self-governing cities in maintaining peace, justice, and prosperity, and in guaranteeing the welfare and happiness of the governed. The painting cycle argues for the accountability of a republic and against the opacity of tyranny as did the later Florentine humanists.

The Allegory of Good Government is the most medieval part of the cycle with its personifications of virtues on parade.

Ambrogio Lorenzetti, The Common Good of Siena personified and flanked by the Classical Virtues. Romulus and Remus are at his feet. Soldiers lead captive Florentines on the lower right.

Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Pax lounges peacefully, a medieval interpretation of an ancient Roman fragment still housed in the Palazzo Publico.

Ambrogio Lorenzetti, An allegory of Justice from the Allegory of Good Government. Concord sits at the feet of Justice and accepts the end of a chord from a Sienese citizen. The Common Good of Siena holds the other end in his right hand. Citizens hold the chord between them.

The bearded male figure seated in the middle of a long draped bench on the right is the city of Siena (and its common good) personified. He wears the city’s stark black and white in his robes. Public classical virtues flank him on the right and the left. To the right, moving from left to right, are Magnanimity, Temperance, and Justice. To the left of Siena, moving from right to left, are Prudence, Fortitude, and Peace, who lounges on the arm of the throne. Flying around Siena’s head are the three private Christian virtues of Faith and Hope with Charity at the top. Romulus and Remus suckle the she-wolf at the foot of Siena (the Sienese claimed Remus as the founder of their city). To the right of the founding brothers, victorious soldiers present captives (perhaps captured Florentines in a fond remembrance of Siena’s great unexpected victory at Montaperti in 1260).

Citizens to the left of the brothers hold a chord that begins in the right hand of Siena. The other end is held by the figure of Concord who sits at the feet of an elaborate allegory of Justice, both criminal justice on left, and civil justice on the right.

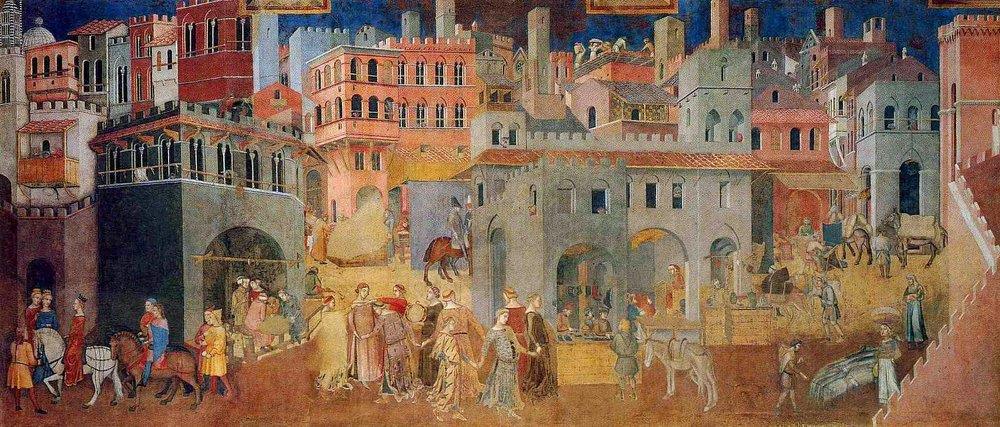

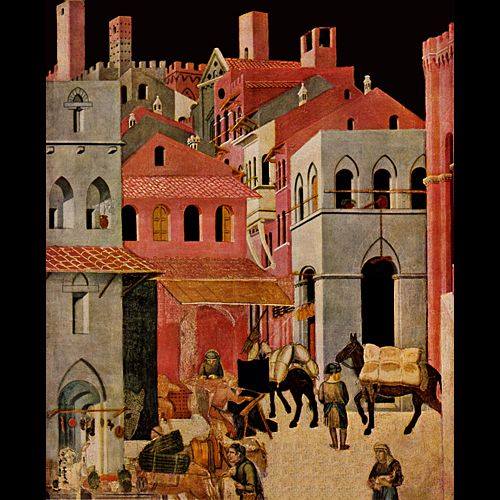

The allegory on the end wall belongs to the Middle Ages, to the world of allegories and symbols, but the long side wall is truly revolutionary. It shows the effects of Good Government in the city and in the surrounding countryside. Ambrogio shows these virtues lived out in the city of Siena itself. Instead of showing a generic typical city, or an appropriately symbolic city from ancient literature or Scripture, Ambrogio paints Siena itself in a striking and still vivid portrait of the city.

Reflecting the influence of Giotto and Maso di Banco, Ambrogio uses the setting to tell the story, and it’s a very particular setting. He very skillfully piles up the buildings on oblique angles and has streets coming and going at odd angles, as can still be seen in Siena today. We see a bustling prosperous city full of activity. There is a shoe shop, and next to that, a scholar lectures students. In the center, very fashionably dressed women dance in the street (something that was illegal in Siena at the time). As we go up in the painting, we see horses and pedestrians appearing and disappearing around corners. Laundry hangs on wooden poles outside windows. Construction workers lay bricks on the very economical scaffolding of that time set right into the walls (you can still see these now pigeon infested holes in stone and masonry walls all over the city; I presume that they were left open for maintenance scaffolding; timber is still scarce around Siena). Ambrogio brilliantly realizes the experience of traveling through the actual hill-top city.

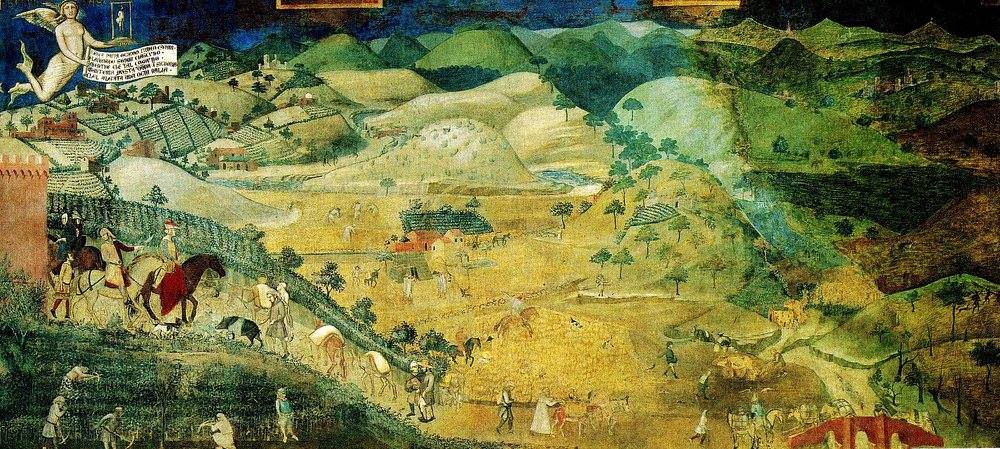

To the right of the city, occupying half of the wall, is the effects of Good Government in the surrounding countryside. This is one of the first masterpieces of landscape in Western art, a remarkable recreation of the Tuscan countryside that still can be seen right out the window of the Sala de’ Nove.

The gently rolling hills of the Tuscan landscape, covered with fields and vineyards, recede by stages into the distance in the painting, just as they do in life. The vegetation is spotty in the heavily cultivated landscape just as it is in the Sienese countryside today. As in the city, the countryside bustles with activity with peasants harvesting and tending vineyards. Peasants in the foreground drive donkeys loaded with sacks of grain for sale in the city. Another drives a pig to sell to the butcher. Fashionable young nobles emerge from the city gate to go hawking and meet the peasants. Significantly, they pursue their noble pastime in the stubble of already harvested fields instead of in standing wheat (as Frederick Hartt points out).

Hovering above the gate between the city and the country is a personification of Security, perhaps based on the flying figure of a Roman Victory. She holds a gallows and a scroll with and inscription saying that Just Government denies power to the wicked.

On the opposite wall is the Allegory of Bad Government with its effects. This painting is heavily damaged, perhaps deliberately because of its subject matter. Tyranny sits surrounded by vices in an inversion of the Allegory of Good Government. Everything goes to hell in hand-basket in a Siena unjustly governed.

The ideas behind Ambrogio’s cycle are still firmly rooted in Medieval thought. The purpose of government is to assist in the Christian project to save souls by securing peace and prosperity, and by promoting virtue and prohibiting vice. Ambrogio presents this idea in medieval terms of allegory on the end wall. What is really new and forward looking is his application of those concepts to the actual experience of living in the city of Siena at that time.

For more great art history read Douglas’ Counterlight and Follow him on Facebook.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.