Can pornography work as social commentary and satire? Can porn be a catalyst for change? In the lead up to the French Revolution, Marie Antoinette was the subject of sexual fantasy brought to the masses in ribald pamphlets.

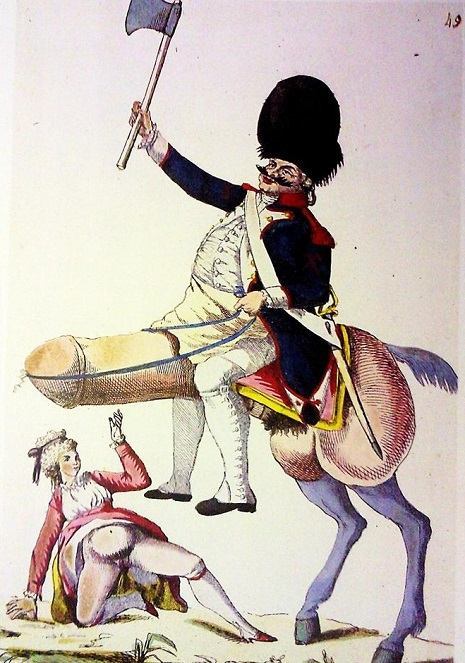

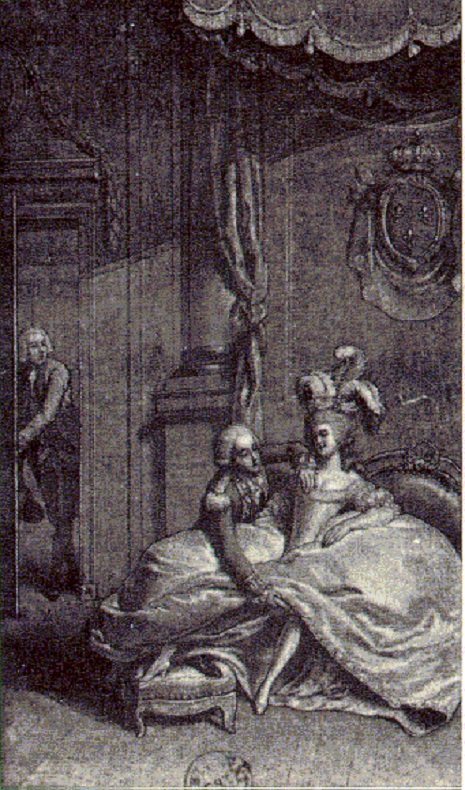

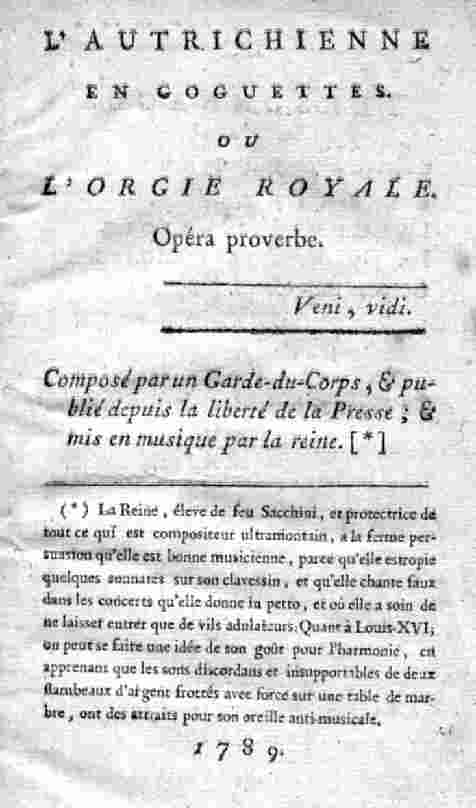

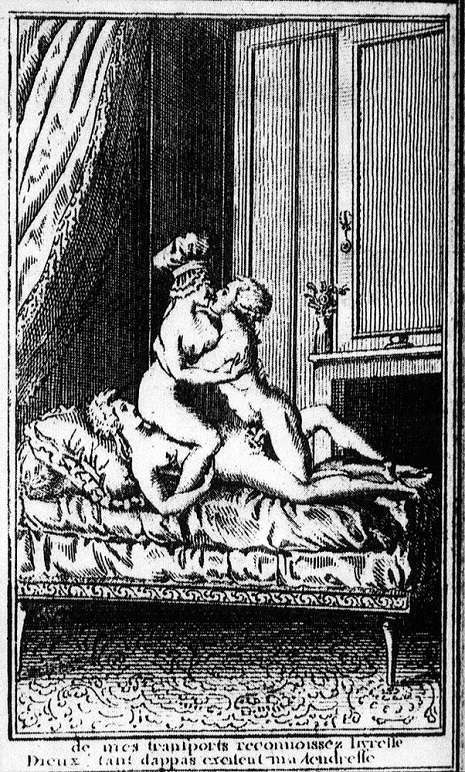

The frontispiece of ‘The Austrian Bitch and the Royal Orgy’, a 1789 opera (via)

The anti-aristocrat novel Les Amours de Charlot et Toinette (1779) was based on the supposed secret life of Marie, depicted as a wanton hussy unsatisfied by her pasionless, impotent husband, King Louis XVI. In it the king’s penis is “no bigger than a straw/ always limp and always curved/ he has no prick, except in his pocket/ instead of fucking, he is fucked.” Other tales intended to undermine the Ancien Régime included: The Royal G. (1789) and L’Autrichienne en Goguettes ou l’Orgie Royale (‘The Austrian bitch and her Friends in the Royal Orgy’ .

In a contemporary pamphlet entitled Vie de Marie-Antoinete d’Autriche, it is written:

“Since the Revolution, the monarchist club, whose body and soul is Antoinette, have been continually at it; all its members have drawn from the vagina of the Austrian Woman…That infectious cavern is the receptacle of all vices, where each comes and takes his required dose.”

And (via):

“Even during her final imprisonment, she offered her guards the flowing shocking exhibition: With her right hand, the princess de Lamballe foraged her bush, which was often dripping with sweet juices. With her left hand, she masterfully and rhythmically slapped one of the royal buttocks…They saw princess de Lamballe pull a kind of dildo out of her pocket, which she then applied to that spot we take our joy in. It was attached with a wide ribbon, which fitted over her hips most gracefully.”

… if we envision the pornography of the last two hundred years as designed solely to titillate and incite sexual feelings, we must view its history before this time as a form of expression that used the shock of sex as an instrument to convey other messages, often censuring political or religious figures, but also directly challenging social and moral conventions. “Pornography was the name for a cultural battle zone,” wrote Lynn Hunt; quoting the historian Walter Kendrick she continued, “’pornography’ names an argument, not a thing.” This fact is clearly evident if one examines the basis of government regulation during this era, which was focused on repression of unrest and sedition rather than expurgation of licentious material in the name of public decency.

Libelle pamphlets were powerful:

Though it was during the Revolution itself, and directly preceding it, that the largest effusion of political pornography was released, between the years of 1787 and 1792 there were important precursors that would later shape the direction of revolutionary erotic libel. To be sure, all political elites, be they revolutionary or royalist, got a healthy dose of pornographic censure. But the orientation of this material was aimed disproportionately toward Marie Antoinette. “The avalanche of defamation that overwhelmed her between 1789 and her execution on October 16, 1793, has no parallel in the history of vilification[”, wrote historian Robert Darnton. Perhaps the most shocking evidence of the libel’s widespread dissemination comes from Boyer de Nîmes’s Histoire des caricatures de la révolte des Francais in which Boyer notes that “antiqueen pamphlets were sold at the gate to the Tuileries palace, in its gardens and right under the King’s window.” These rumors of erotic manipulation and debauchery were so vast as to replace the real Marie Antoinette with a ribald fiction where imagined narratives of her private life rode roughshod over any actual movements the Queen might have made.

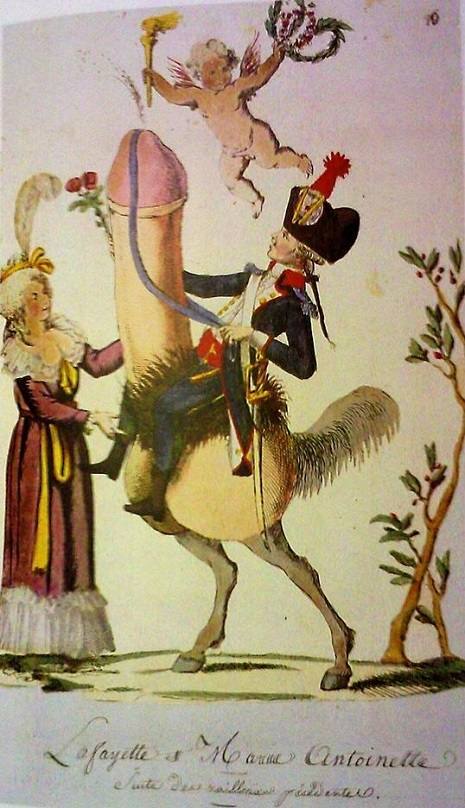

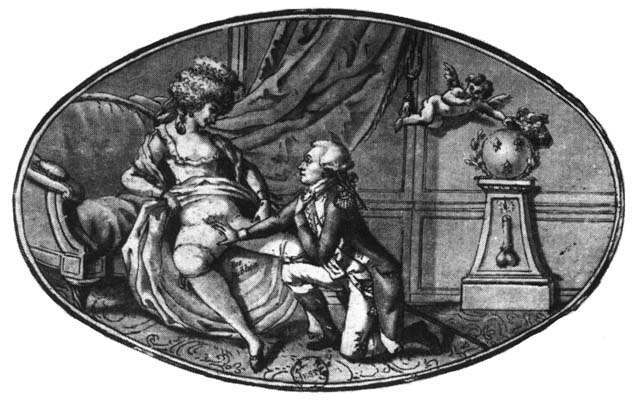

Above is a cartoon from 1789 showing General Lafayette on bended knee fondling the exposed “res publica” of Marie Antoinette. Via

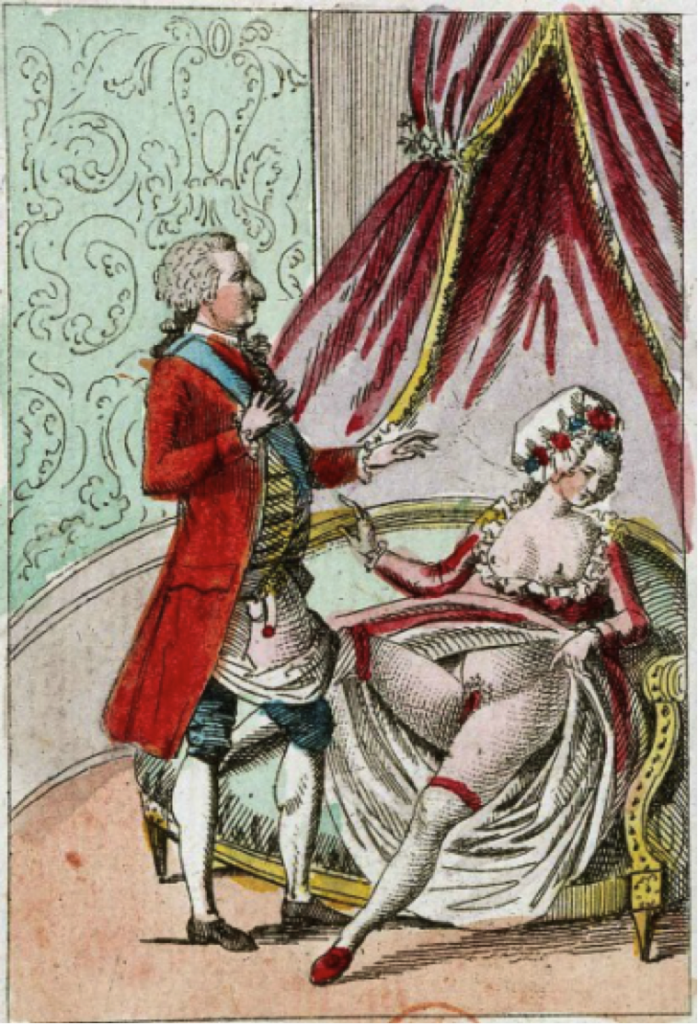

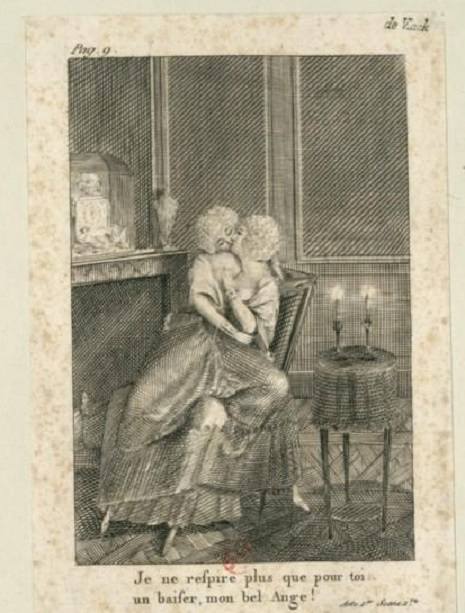

Marie in an orgy. ““Witness the ecstasy of my throes. Gods, so many bosoms excite my tender affection.”

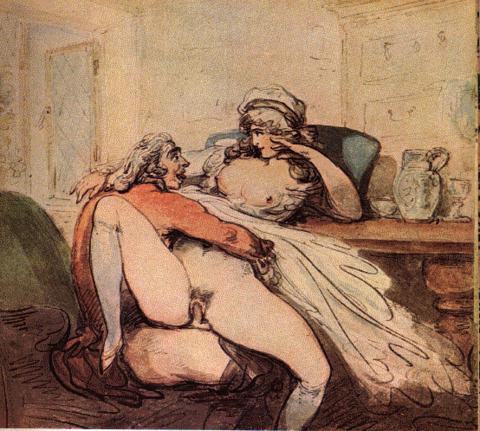

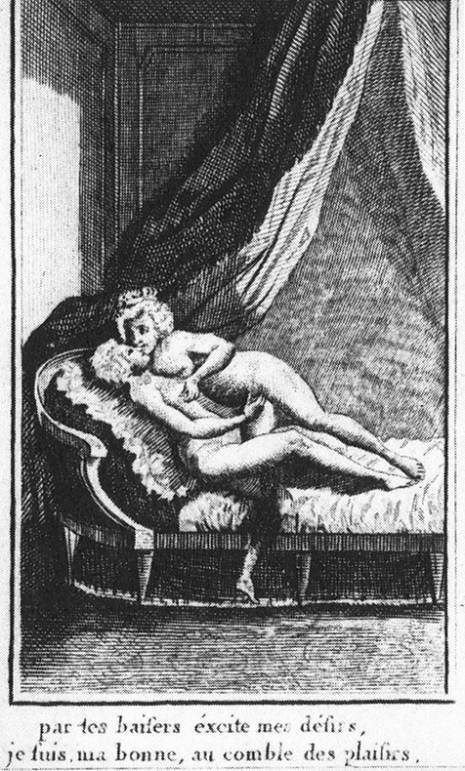

Typical lesbian depiction involving Marie Antoinette and the duchess of Pequigny. Louis Binet. From Marie-Jo Bonnet, Les Deux Amies (paris: Éditions Blanche, 200). Accessed at

Text reads: “With your kisses, excite my desires, I am, my darling, at the height of pleasure.” Via

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.