“It is advisable to look from the tide pool to the stars and then back to the tide pool again.”

– John Steinbeck, The Log from the Sea of Cortez

Do we give to receive? And if we do, when we receive, how should we behave? John Steinbeck (February 27, 1902–December 20, 1968) considered the art of giving and receiving in an essay about his friend Ed Ricketts (May 14, 1897 – May 11, 1948), the co-author of the book Sea of Cortez (1941) and model for the character of Doc in Cannery Row. After Ed was hit by a train and killed, Steinbeck thought about “the great talent that was in Ed Ricketts, that made him so loved and needed and makes him so missed now that he is dead”.

Ed’s talent, Steinbeck reasoned, was “his ability to receive, to receive anything from anyone, to receive gratefully and thankfully and make the gift seem very fine. Because of this everyone felt good in giving to Ed — a present, a thought, anything.”

In the The Log from the Sea of Cortez (1951), a reworking of the earlier 1941 book, Steinbeck pays tribute to his late friend:

Perhaps the most overrated virtue in our list of shoddy virtues is that of giving. Giving builds up the ego of the giver, makes him superior and higher and larger than the receiver. Nearly always, giving is a selfish pleasure, and in many cases it is a downright destructive and evil thing. One has only to remember some of our wolfish financiers who spend two-thirds of their lives clawing fortunes out of the guts of society and the latter third pushing it back.

It is not enough to suppose that their philanthropy is a kind of frightened restitution, or that their natures change when they have enough. Such a nature never has enough and natures do not change that readily. I think that the impulse is the same in both cases. For giving can bring the same sense of superiority as getting does, and philanthropy may be another kind of spiritual avarice.

Virtue signalling, donor hubris, welfare capitalism and the myriad ways the rich give to receive can be well met by the recipient. Best to focus less on the giver’s grandstanding and see the gift for what it is. Be self-aware and your gratitude becomes a virtue:

It is so easy to give, so exquisitely rewarding. Receiving, on the other hand, if it be well done, requires a fine balance of self-knowledge and kindness. It requires humility and tact and great understanding of relationships. In receiving you cannot appear, even to yourself, better or stronger or wiser than the giver, although you must be wiser to do it well.

It requires a self-esteem to receive — not self-love but just a pleasant acquaintance and liking for oneself.

By way of an addendum, the psychologist Martin Seligman has some more advice, via Robert Klitgaard, who writes:

We feel grateful for a gift, be the gift an object or a kindness or a courtesy or sheer grace. Gratitude is a feeling of joy and the desire to reciprocate. Gratitude may sometimes be accompanied by a sense of indebtedness or obligation, but its essence is a feeling quite unlike anything that accompanies a payment or a contract. A disposition to gratitude helps and encourages us to carry out our responsibility in life, which is to grow in love.

Segilman notes (paraphrased by Kligaard):

Once we are resolved to be more grateful, here are two things we can do that research has show to be successful:

Keep a “gratitude journal” for recording all the reasons, events, and help received that merit your gratitude, past and present and as they occur in the future. A number cof studies have randomly assigned subjects to keep three kinds of journals. One group records specific things they are thankful for. Another group records things that have bothered them that day. And a third group receives the neutral instruction to write down some of the things that happened that day. The results: the grateful group is happier, more successful in fulfilling their goals, exercises more, and reports better relationships with others

A second idea is to write a gratitude letter. Professor Seligman developed this intervention, which he now uses in class as well. You think of someone to whom you are grateful but whom you have never properly thanked. You compose a 300-word testimonial to that person. And then you deliver it in person, not telling the purpose, just saying “I want to come over and see you.” The results are emotional, and then measurable months later.

Klitgaard leaves us with a question: ‘Does behavior tend to follow attitudes, or do attitudes tend to follow behavior?”

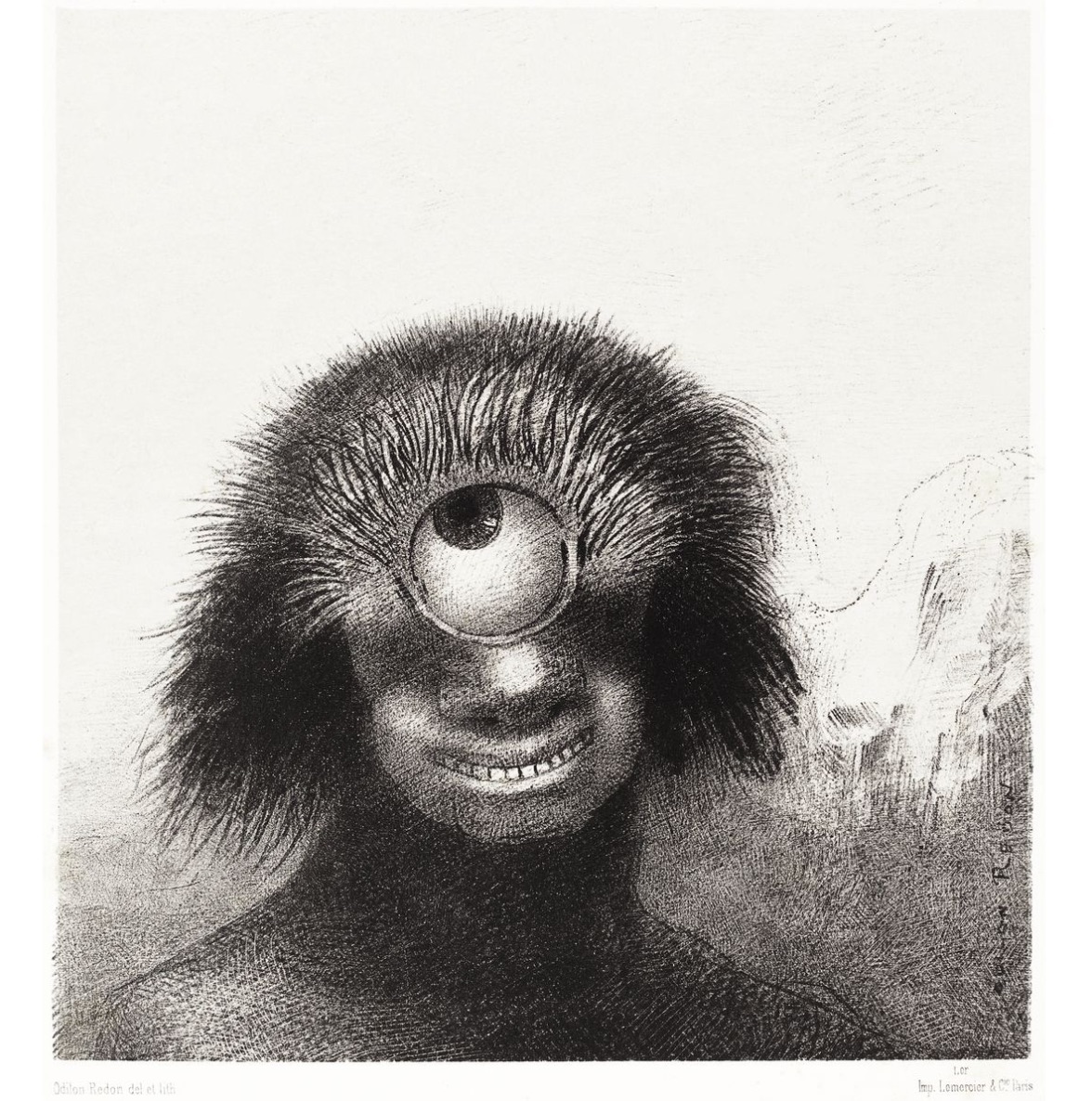

Lead Image: Deformed Polyp Floated on the Shores – Odilon Redon

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.