Once a target of critical abuse—its name the reclamation of an insult—Brutalism is back, in a “long overdue intellectual revival.” The monumental concrete behemoths that characterize its style have been associated with faceless modernist excesses, the former Yugoslavia and decaying ex-Soviet republics, soulless, inhumane public housing. Some of the negative associations stick, in the case, for example, of Le Corbusier’s influence on city planners like Robert Moses, who tore up New York City neighborhoods and turned them into project housing resembling prison complexes.

When executed with ingenuity and, often, a sense of humor, Brutalist architecture gave the world some of the most stunning modern buildings ever created. “What was and still is appealing about Brutalism is that it had a kind of purity to it,” writes Nikil Saval at The New York Times. “Its deeper appeal is moral. In the words of Reyner Banham, it was an attempt to create an architectural ethic, rather than an aesthetic.” Manifesting all over the world, Brutalism is “the vernacular expression of the welfare state. From Latin America to Europe to South Asia, Brutalism became the style for governments committed to some kind of socialism, the image of the ‘common good.’”

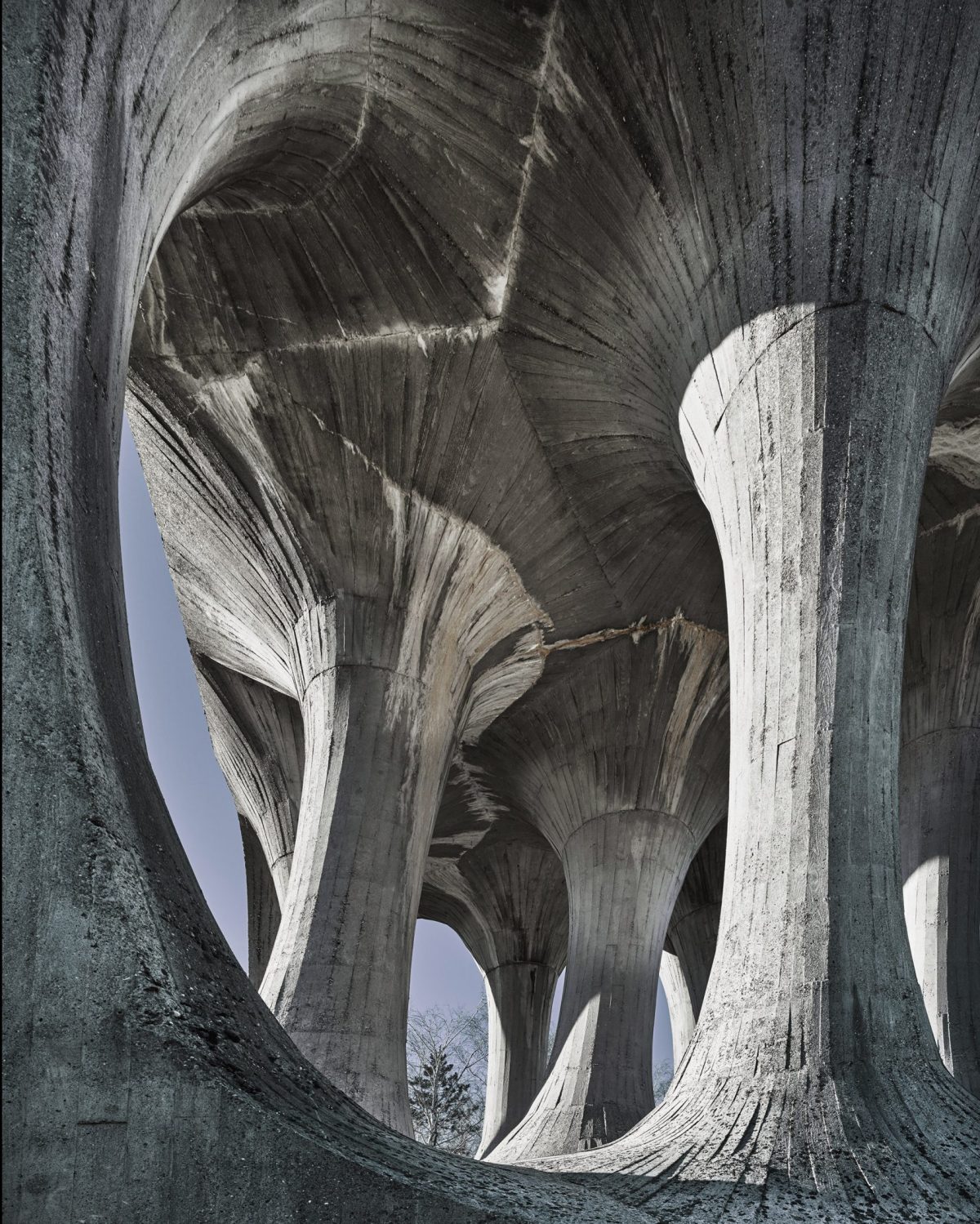

How much it served the common good there is debatable, but the former Yugoslavia offers many prime examples of stark, unyielding Brutalist architecture, many of them now abandoned or neglected. In his series Toward a Concrete Utopia: Architecture in Yugoslavia, 1948-1980, Swiss photographer Valentin Jeck explores these office buildings, housing complexes, skyscrapers, monuments, libraries, etc.

The photos, like the buildings themselves, are grimly monochromatic, taken under dramatically cloudy skies. Aside from the gray color palette, the swooping, towering, cavernous concrete and glass structures could not be more different from each other, defying a popular notion that mid-century modernist architectural principles produced a soul-crushing sameness. Jeck’s exhibit also features more than 400 drawings, models, photographs, and film reels, “culled from an array of municipal archives, family-held collections, and museums across the region.” It will be open at the Museum of Modern Art until January 13, 2019.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.