During the height of the summer of 1929 the Daily Mail, only a couple of months after it had complained about the possibility of women not wearing stockings at Wimbledon, wrote:

It seems to be universally agreed that male dress at the present time is the most unhygienic, inartistic, sombre, and depressing form of costume that the mind could well imagine. But the difficulty is to get the idea of a brighter, more hygienic, and more picturesque attire into the mind of the mere male.

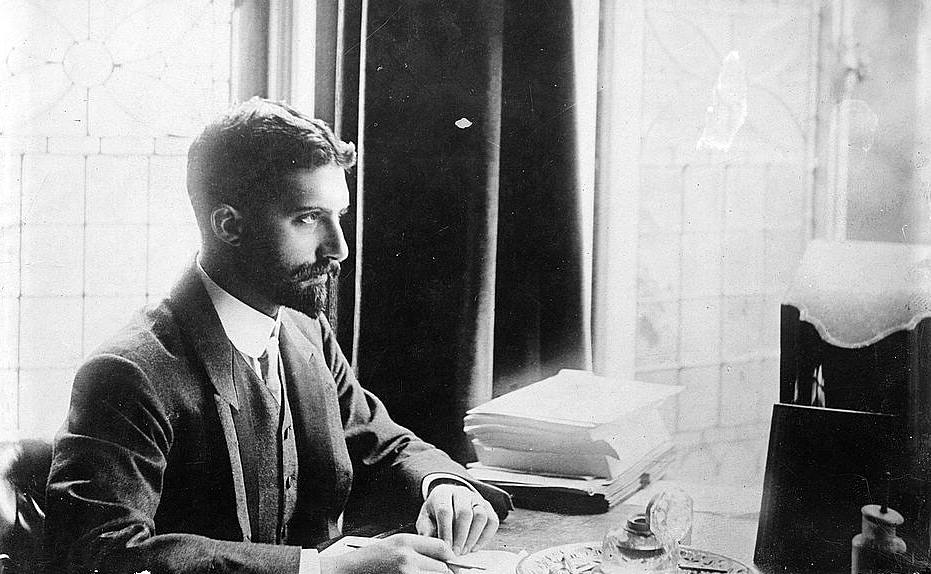

One London newspaper had recently published a photograph of the renowned radiologist Dr Alfred Charles Jordan cycling to his office in Bloomsbury. What fascinated and slightly horrified the readers was that the picture showed him wearing shorts with his jacket. This was utterly unknown at the time for anybody working in a city – shorts were for Scouts, sport, and maybe a hiking holiday. They weren’t even worn by men playing tennis at the time. Jordan was the honorary secretary of the Men’s Dress Reform Party which had announced its existence on 12 June 1929. The first aim of the new organisation was to improve men’s health by changing what they wore and early MDRP literature complained that:

Men’s dress has sunk into a rut of ugliness and unhealthiness from which – by common consent – it should be rescued…Men’s dress is ugly, uncomfortable, dirty (because un-washable), unhealthy (because heavy, tight and unventilated)…it is desirable to guard against the danger of mere change for change’s sake, such as has often occurred in women’s fashion. All change should aim at improvement in appearance, hygiene, comfort and

convenience.

1930 A rally for shorts at Dartmouth College in 1930

Admittedly most men at the time would have taken some convincing to wear this new style of clothing, however an article in the tailoring magazine Tailor and Cutter thought the wearing of such attire was close to the end of civilisation:

If laces are unfastened, ties loosened and buttons banished, the whole structure of modern dress will come undone; it is not so wild as it sounds to say that society will also fall to pieces … Such restraints were not noxious: they were the foundation upon which civilisation rested and protected men from savagery and decadence.

A man called D. Anthony Bradley agreed and spoke at a debate in 1932 entitled ‘Shall Man be Redressed?’. Mr Bradley patently thought not and argued:

The man who, alone in the jungle, changes into his dinner jacket does so to convince himself that he is not a savage – soft sloppy clothes are symbolic of a soft and sloppy race … It did not matter very much what health cranks, exhibitionists or men of misplaced sex wore, man – sturdy and virile man, capable of withstanding the rigours of a stiff shirt, must maintain conservative standards of dress.

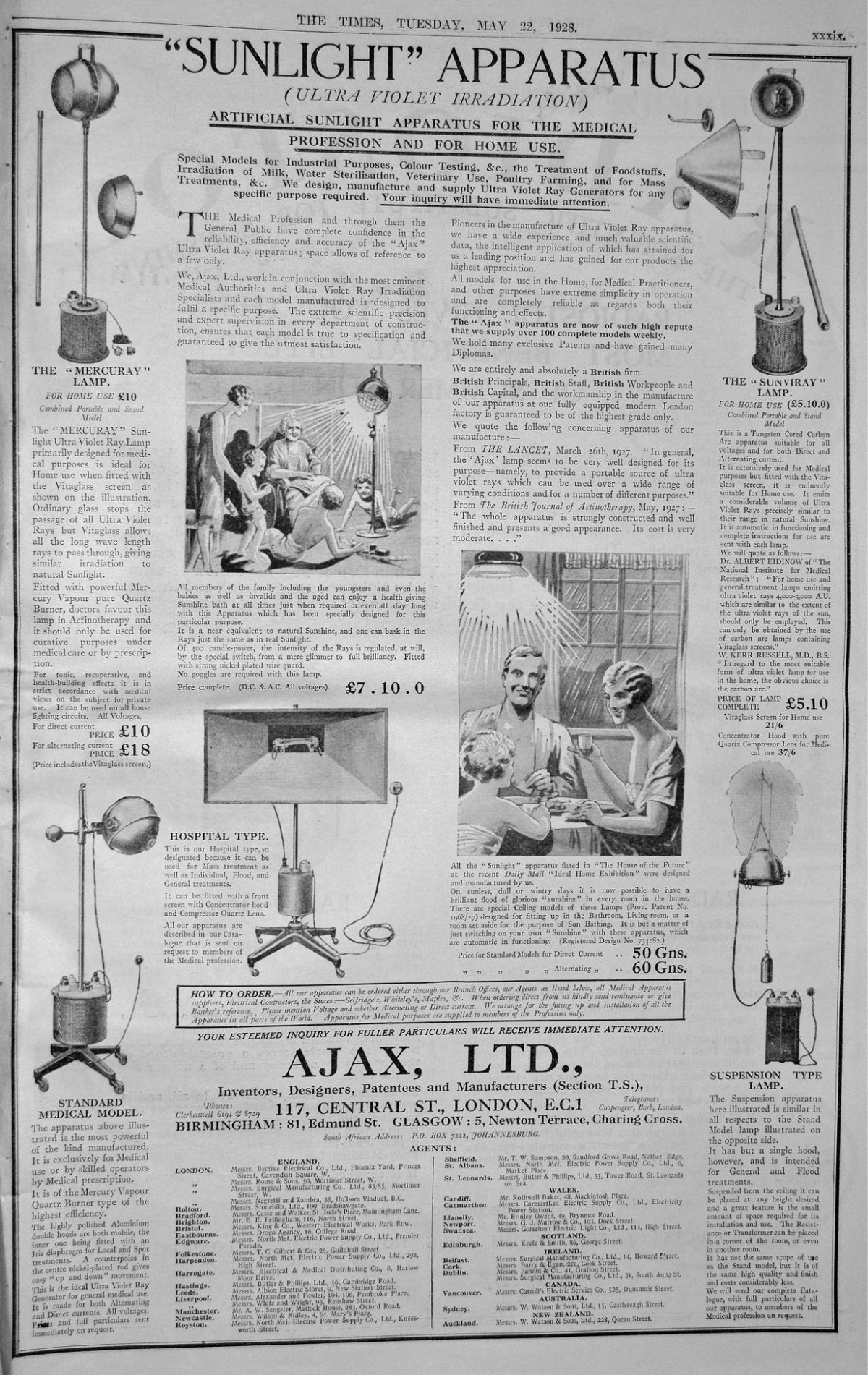

The MDRP was an off-shoot of, and shared premises with, the New Health Society formed in 1925 and situated at 39 Bedford Square in Bloomsbury. The chairman of the MDRP was another doctor, Caleb William Saleeby, who had originally chaired the clothing sub-committee of the New Health Society but had also founded the Sunlight League in 1924.

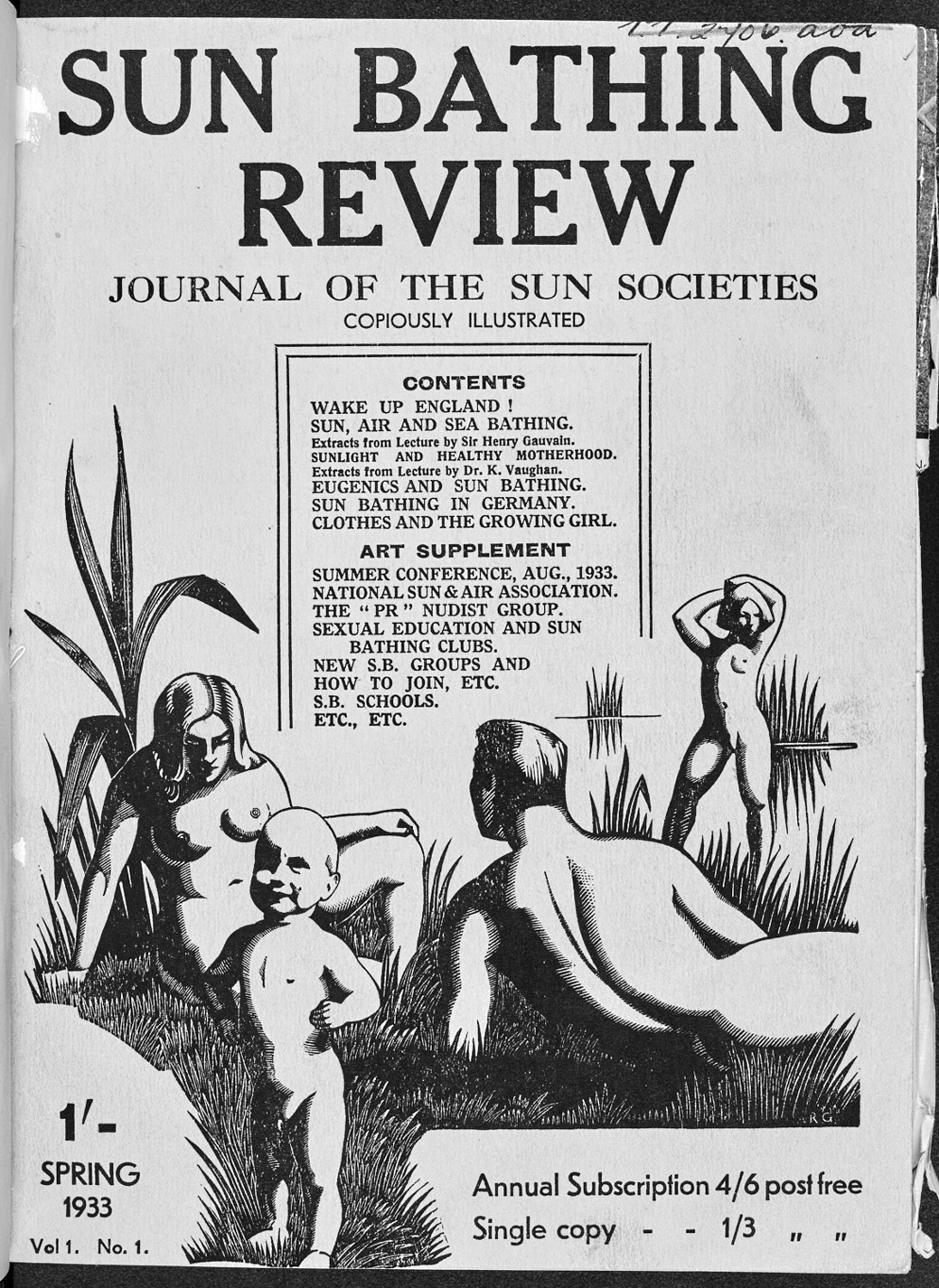

The Sunlight League had been formed in London to educate the public about ‘Nature’s universal disinfectant, stimulant and tonic’ and advocated heliotherapy – direct exposure to the sun. The league campaigned for a variety of causes including mixed sunbathing and the relaxation of the rules for what was considered appropriate attire when in the sun. Towards the end of the 1920s, new-fangled sunbathing clubs were opening around London, including Finchley and Sidcup, while the Yew Tree Club, devoted to physical culture and nudity, opened in Croydon. Compared with on the continent, especially in Germany, nudism remained a minority activity in England and it rarely strayed from its suburban, Home Counties roots. The clubs had strict conventions, and rules of etiquette were designed to convince a doubting public that sex was the last thing on the nudists’ minds. And maybe it was.

Dr Saleeby, as chairman of the MDRP, wrote a letter to the Lawn Tennis Association in 1929 encouraging it to ‘persuade men to give up the handicap of heavy trousers and play in shorts’. Everyone knows that the first man to have worn shorts at Wimbledon was Henry ‘Bunny’ Austin (his nickname comes from a character in the comic strip ‘Pip, Squeak and Wilfred’) in 1932. Except he wasn’t. The first man to experience fresh air against his legs while playing tennis at Wimbledon was actually the relatively unknown English player Brame Hillyard. A year after Saleeby’s letter, the fifty-six-year-old Hillyard wore them on Court 10. Despite the freedom his shorts must have given him, he promptly lost, and he was hardly ever heard of again.

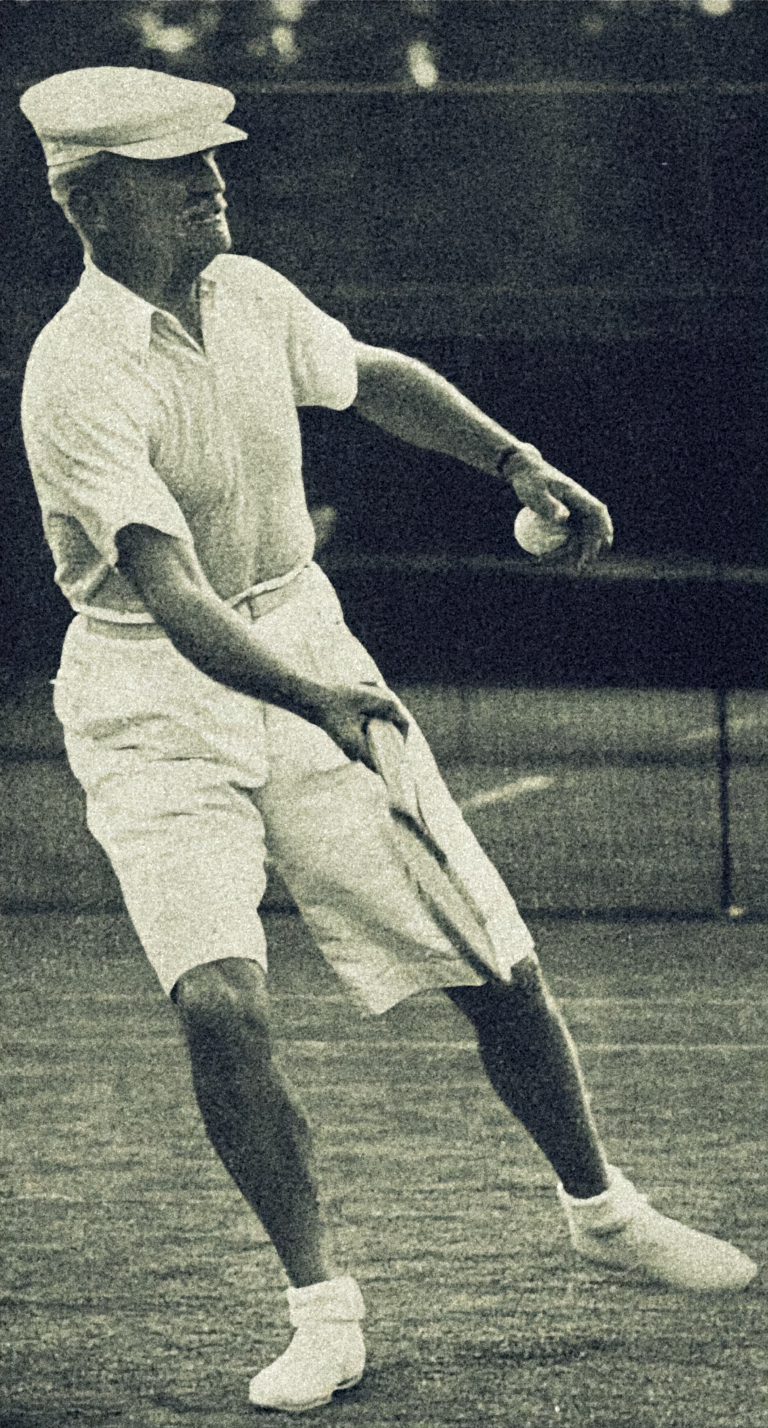

Brame Hillyard was the first ever person to wear shorts (rather than trousers) at Wimbledon – on Court 10 in the 1930 tournament, aged 53, The Bystander, 2 July 1930

English tennis player Bunny Austin (1906 – 2000) competing against Keith Gledhill of the USA in the third round of the Men’s Singles at Wimbledon, London, 1933. Austin won the match 6-3, 10-8, 6-1.

27th July 1937: British player Henry Wilfred ‘Bunny’ Austin (1906 – ) having a cup of tea after being defeated by an American, Donald Budge (1915 – ) in the closing stages of the Davis Cup at Wimbledon. (Photo by Hudson/Topical Press Agency/Getty Images)

1928 Rene Lacoste and Bunny Austin (still with long trousers) ahead of their fourth round match on centre court. Lacoste would go on to win the mens title.

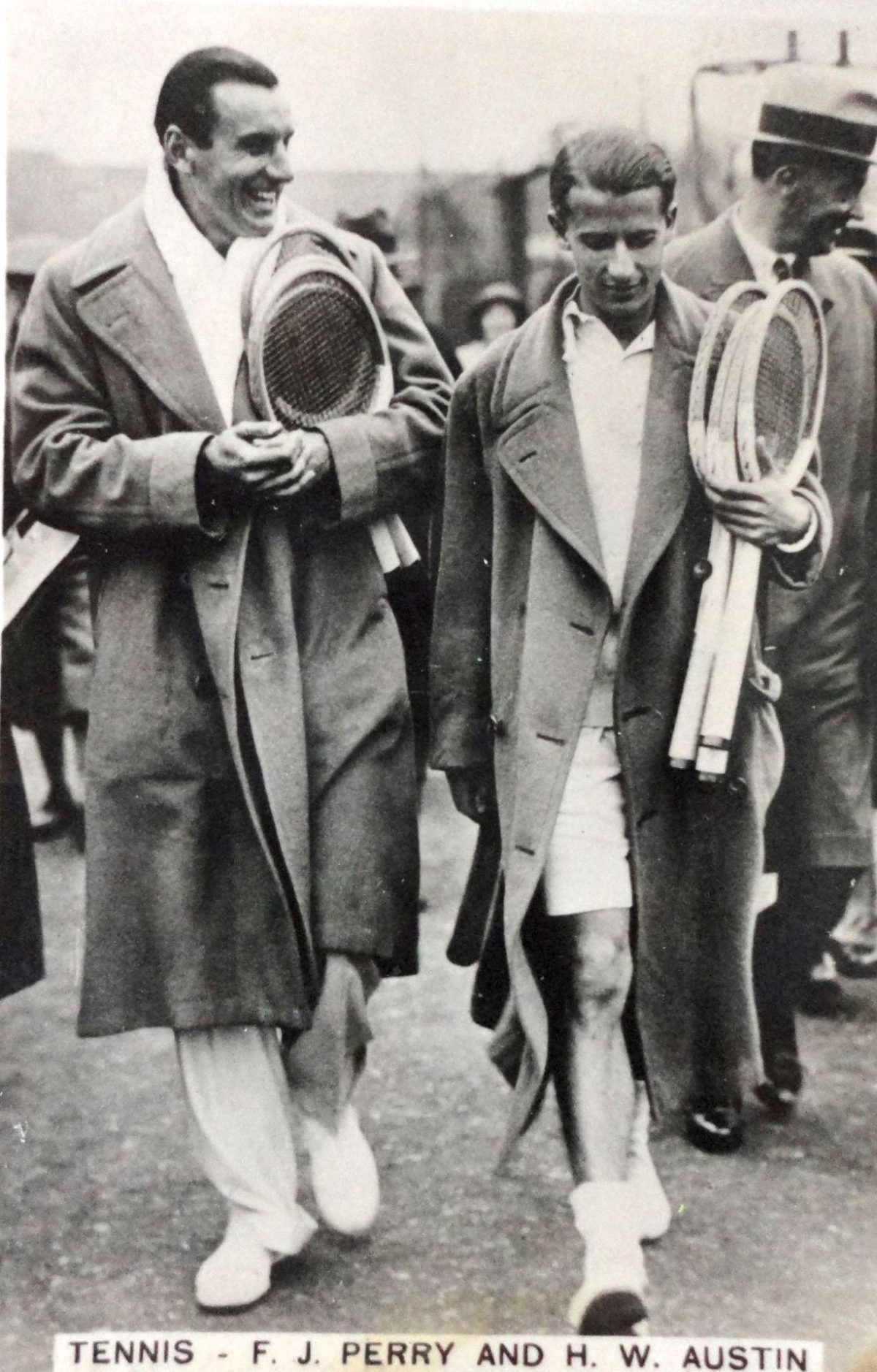

Fred Perry and the shorts wearing ‘Bunny’ Austin

Two years later, in 1932, the twenty-four-year-old Henry Wilfred ‘Bunny’ Austin, born in South Norwood, eight miles or so away from Wimbledon, but educated at Repton and Cambridge, became the first person to wear shorts on Centre Court, and thus the first in front of the world’s press. A man wearing shorts to play tennis looks utterly normal these days, but in the early 1930s it attracted much derision. John Kieran wrote about Austin in the New York Times that year:

With his white linen hat and his flannel shorts, the little English player looked like an AA Milne production.

Austin actually had to overcome considerable embarrassment when he decided to wear shorts for the first time and it wasn’t an easy decision:

I myself took over two years to summon up enough courage to wear shorts, although for years I had known how much more healthy, comfortable and reasonable they were for tennis. I hovered in my bedroom…putting them on, taking them off, putting them on again, wrestling with the problem of Hamlet – ‘to be or not to be’. At last I summoned up all my courage, put and kept them on, and waring an overcoat to conceal them as much as possible, went out of the hotel to play. My bare legs protruded beneath the coat and I slunk through the lounge self-consciously. As I passed through the door an agitated porter followed me. ‘Excuse me, Mr Austin’, he whispered diffidently, ‘but I think you’ve forgotten your trousers.

Bunny Austin lost in the final to the American Don Budge, who was happy to be weighed down by his long flannel trousers. The Englishman’s reward as runner-up was a £10 gift voucher redeemable at a high-street jeweller’s. Austin was the last English man to appear in a Wimbledon Singles Final, when he was again runner-up in 1938. During the war he became active in the Christian pacifist movement and lived in the US. He was criticised in the press as a conscientious objector. It wasn’t until 1984 that Austin was again allowed to be a member of the All-England Club.

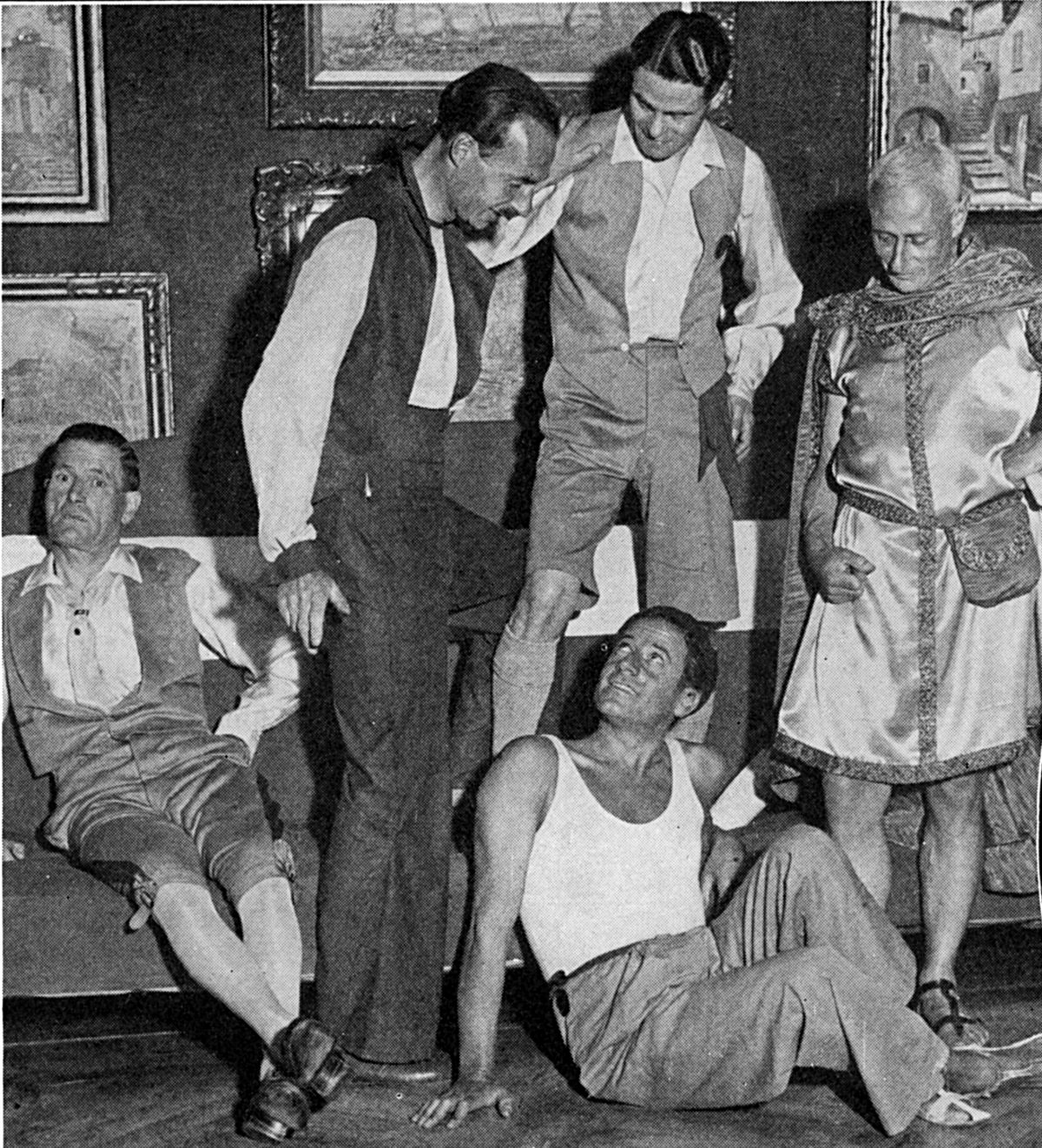

1937 Members of the Men’s Dress Reform Party in London. David Savill

The MDRP, almost forgotten these days, had some success in getting its message across during the first years of its existence. It held annual parties, in order to ‘give every man a chance to show how he can look and feel his best by the costume he will evolve for this unique occasion’, and it was possible to find MDRP approved clothing in some shops in London, including the famous Austin Reed on Regent Street. It also had an official shop and a relatively successful mail-order service. In 1937, the Men’s Dress Reform Party lost the support of the New Health Society because of financial trouble and eventual bankruptcy. Then, in 1940 the Sunlight League was wound up. A bomb destroyed their offices and then the founder, Dr Saleeby, died that year too. There is no evidence of the Men’s Dress Reform Party continuing to exist after this date.

The MDRP, realistically, did little to turn general male fashion around except maybe in holiday and athletic wear. A major shift in men’s clothing didn’t happen until after the war, when new fabrics and the rise of American style, with its preoccupation with leisure-wear, radically changed men’s appearances in the 1960s.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.