The post-war variety show Piccadilly Hayride at the Prince of Wales Theatre in London’s West-End is remembered for the comedian Sid Field’s big break. Field became a huge star but has almost been forgotten these days as his occasional film appearances never lived up to his huge success on the London stage. Piccadilly Hayride, however, was also notable for Terry-Thomas’s big break. The gap-toothed comedian who in the decades to come would encapsulate the idea of the caddish English rotter, acted as compère during the revue. He also featured in a spot called Technical Hitch where he played a smooth BBC DJ who, after an accident, finds that all his records are broken. In the spirit of the-show-must-go-on, and with the help of a piano accompanist, Terry-Thomas’s character looks up at a notice that says ‘DO NOT PANIC!’ and pretends nothing has happened by impersonating the vocalists on the broken records, however unlikely. Terry-Thomas would perform this routine, or something like it, throughout his career but always his DJ would finally meet his Waterloo with something utterly impossible to copy like Paul Robeson, Yma Sumac or even the Luton Girls’ Choir …

Terry-Thomas was born Thomas Terry Hoar Stevens in North Finchley in July 1911. His father was a bowler-hatted butcher based at Smithfield Market and it was through him that the young Thomas Stevens got his first job at the centuries-old meat market as a fifteen-bob-a-week junior transport clerk with the Union Cold Storage Company. On his first day, surrounded by blood-stained butcher’s aprons and ash-flecked grey suits, Thomas turned up sporting an olive-green pork-pie hat, a taupe double-breasted suit decorated with a clove carnation, a multi-coloured tie and yellow wash leather gloves, twiddling a long cigarette holder with one hand and twirling a silver topped malacca cane with the other. He soon joined the firm’s amateur dramatic society, and made his debut in AA Milne’s The Dover Road at the Fortune Theatre in Russell Street. He was surprised by the pleasure he got from the applause: ‘The buffoon in me was released … I was able to get laughs at a twitch of a nostril,’ he later wrote.

His first professional engagement as an entertainer was on 11 April 1930 when, at the age of 18 he appeared (billed as ‘Thos Stevens’) at a social evening, organised by the Union of Electric Railwaymen’s Dining Club, in South Kensington. He was paid thirty shillings, not an inconsiderable amount at the time, but despite his best efforts he was a flop and unable to make his boozy audience laugh. He started giving ‘exhibitions’ of dancing with the sister of the musical star Jessie Matthews, while sometimes helping out at the popular Ada Foster School of Dance in nearby Golders Green. For a short while he became a professional ballroom dancer at the Cricklewood Palais de Dance but, despite the attractive women, he was unable to muster the dedication needed. The next job was as a guinea-a-day film extra, and his first speaking part came in 1935 in a movie released the following year called Once in a Million, when he was heard to shout ‘a thousand!’ during an auction scene. He subsequently made publicity cards describing himself as the man who had said ‘a thousand!’ At this time he was still uncredited, but was calling himself Thomas Stevens, which he disliked as too ‘stiff and stuffily suburban’. After rejecting, thankfully, ‘Mot Snevets’ (Tom Stevens backwards) and also Thomas Terry, he eventually decided on Terry Thomas. The all-important hyphen, symbolising the gap in his teeth, arrived nine years later.

T-T with his first wife Pat Patlanski

In 1938 he met and married a ‘very neat, vibrant, well-read and enthusiastic’ South African ballet dancer and choreographer named Ida Patlanski. Pat, as she called herself, was already twice divorced and nine years TT’s senior (at their Marylebone Register Office marriage they both lied about their age, he slightly older, she slightly younger). Together they formed a Spanish dancing cabaret act called ‘Terri and Patlanski’, but for about ‘thirty bob a week’ they were lucky if they were booked at all and had to rely on ‘ghastly clubs’ such as the Paradise Club. Situated at 189 Regent Street, the Paradise had opened in 1935. Members paid seven and sixpence for entrance and, to avoid licensing restrictions, had to order bottles in advance from an agent in Bruton Mews. In its advertising the club described itself as, ‘London’s latest and most exclusive niterie’, but an anonymous letter written in 1937 to the Metropolitan Police Commissioner described it, possibly more accurately, as: ‘nothing but a hotbed of “gentleman” crooks, and prostitutes, the whole place savours of evil and immorality.’ Thomas himself said it was the type of place known in the business as an ‘upholstered sewer’.

ENSA headquarters at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane during WW2

The marriage was short-lived, although at the outbreak of the war they performed together for ENSA (the entertainment wing of the forces, set up by the film and theatre producer Basil Dean) in northern France. When the Nazis invaded, they returned to England but after affairs by both parties they separated (they eventually divorced twenty years later in 1962). Thomas continued to work at ENSA as a solo act, and also became head of the cabaret section of ENSA at its London base at the Theatre Royal in Drury Lane. In March 1942, however, he received a brown envelope containing : ‘a cunningly worded invitation to join the Army’. He accepted the call-up, ‘with dignity, if not enthusiasm’, and joined the Signals Corps in Ossett in West Yorkshire. After about twenty-four hours, a sergeant asked for TT’s number. ‘Mayfair 0736’ was the Londoner’s facetious reply. ‘You ain’t Terry Thomas any more,’ he said , ‘You are now just a fucking number!’ TT replied, ‘Yes mate, Number One!’. The insolence meant that for the next five weeks, at an hour when he used to go to bed, TT found himself having to march over a mile to breakfast each morning. Despite the bad start,TT’s natural competitiveness and dislike of being underestimated meant that he was actually a good recruit and contemporaries said he sounded more like an officer than the real ones. Although he was promoted to sergeant, because of a duodenal ulcer and deafness, he was offered a place in one of the newly formed services-sponsored touring revues called, collectively, Stars in Battledress.

Signed up by Captain George Black, TT’s first official contribution was at an Army show based at Olympia. This was where he began performing the precursor of the Technical Hitch sketch, the inspiration for which came from the plight of a well-known newsreader of the time, called Bruce Belfrage. At 8 pm on 15 October 1940, about five weeks after the start of the London Blitz, a 500 lb delayed-action bomb crashed through the BBC switchboard before coming to rest in the record library on the fifth floor. Staff tried to move it by hand, but during the attempt the timer set off the bomb. Seven BBC members of staff were killed, while much of the fifth and sixth floor frontage of Broadcasting House was blown into Portland Place with glass and debris scattered as far as the junction with Duchess Street. Covered by dust in his basement studio, Belfrage paused only slightly before finishing the nine o’clock news bulletin.

BBC Broadcasting House after the explosion

Despite giving up smoking soon after the war for health-reasons, Terry-Thomas always carried a long, expensive cigarette-holder. When he started smoking as a teenager he hated the thought of his hands being sullied by nicotine-stained fingers. His very expensive suits, made by the tailor Cyril Castle on Savile Row, all had one very special requirement – the breast pocket had to be seven inches deep to accommodate the cigarette holder. In January 1960 Terry-Thomas’s fame was at its height, and he was appearing at a midnight charity event at the Odeon Theatre in Liverpool. After coming off stage and getting back to his dressing room, he soon realised that his expensive custom-made cigarette holder was missing. It wasn’t just any old cigarette holder; this one was particularly ostentatious and decorated with forty-two diamonds and a gold spiral band. It was insured for £2000. The Liverpool police didn’t take long to track down two of the diamonds, which they found at the home of a local unemployed salesman and well-known ‘fence’ called Alan David Williams.

The other 40 diamonds were found inside a roll of carpet at the Queen’s Drive home of a 20 year old small-time variety comedian called James Joseph Tarbuck. Alan Williams was charged with being an accessory after the fact and Tarbuck with theft, and they were both committed for trial at Liverpool Magistrates’ Court in April 1960. At the trial it came to light that Tarbuck had repeatedly asked Terry-Thomas if he too could perform at the charity gig. The star had pointed out to him that they had too many artistes already and it ‘would be madness to put anybody else on’. Mr. F. V. Renshaw, the prosecutor, revealed that Tarbuck had said: ‘I rang Terry-Thomas and he promised me a three-minute spot on the show, but by the finale I still hadn’t been on.’ The Liverpudlian, once a class-mate of John Lennon’s, said of his humiliating rebuff, ‘I was disgusted. I was walking out of the theatre when I saw the cigarette holder on the dressing table, and took it. I had it broken up and I was going to throw it away.’ The defence maintained that it was ‘a moment of pique rather than dishonest intent’, although they admitted that Tarbuck was deeply in debt. Both men pleaded guilty and James Tarbuck was put on probation for two years, while Williams was given a 12-month conditional discharge.

At the end of the court case, T-T left the building, gave one of his famous broad gap-toothed grins and conspicuously waved around another very expensive cigarette holder to the waiting reporters. Just over three years after the court-case, the unemployed Liverpudlian pub comedian, now twenty-three, appeared on the ATV show – Sunday Night at the London Palladium. After his eight-minute joke session, Tarbuck was given one of the biggest receptions the show had ever known. Despite Associated Television staff trying to calm the audience down so that the rest of the production could continue, the cheering just went on and on. It only stopped when the new discovery was brought back to take an extra bow.

25th September 1954: English actor-comedian Terry Thomas (1911 – 1990), real name Thomas Terry Hoar-Stevens, demonstrates how an exhausted husband slaves late into the night, to keep his wife in idleness and luxury. Original Publication: Picture Post – 7292 – When A Man Is Kept Late At The Office – pub. 1954 (Photo by Bert Hardy/Picture Post/Getty Images)

Terry-Thomas & Doris Day in Where Were You When the Lights Went

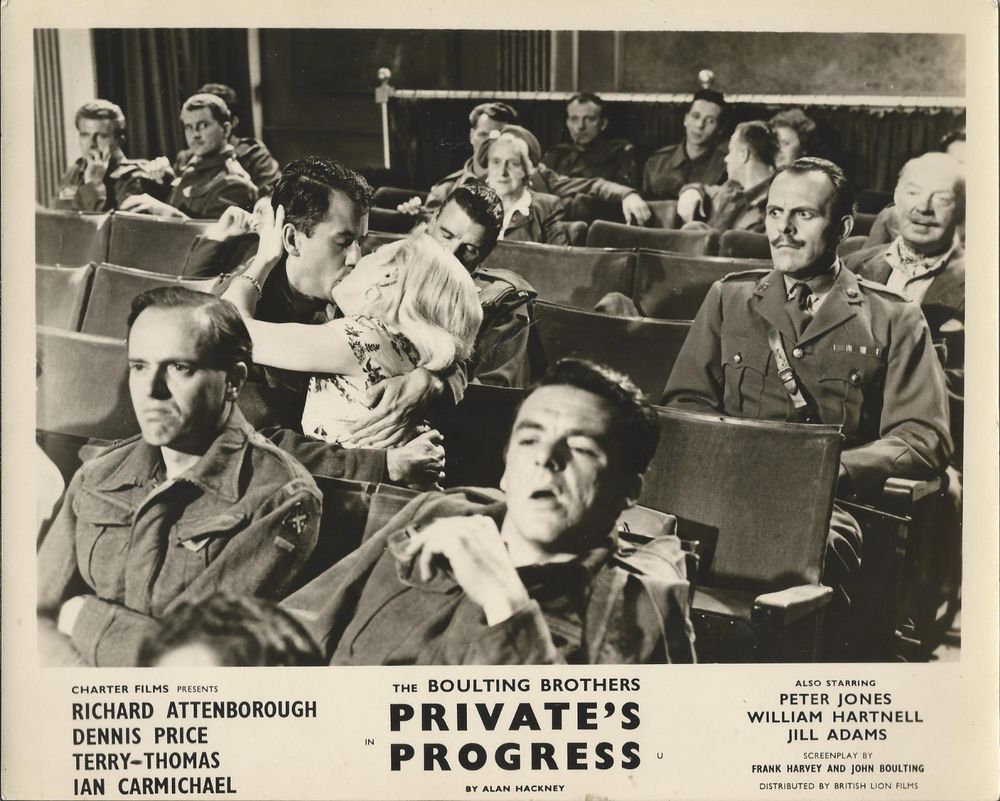

Private’s Progress directed by John Boulting in 1956

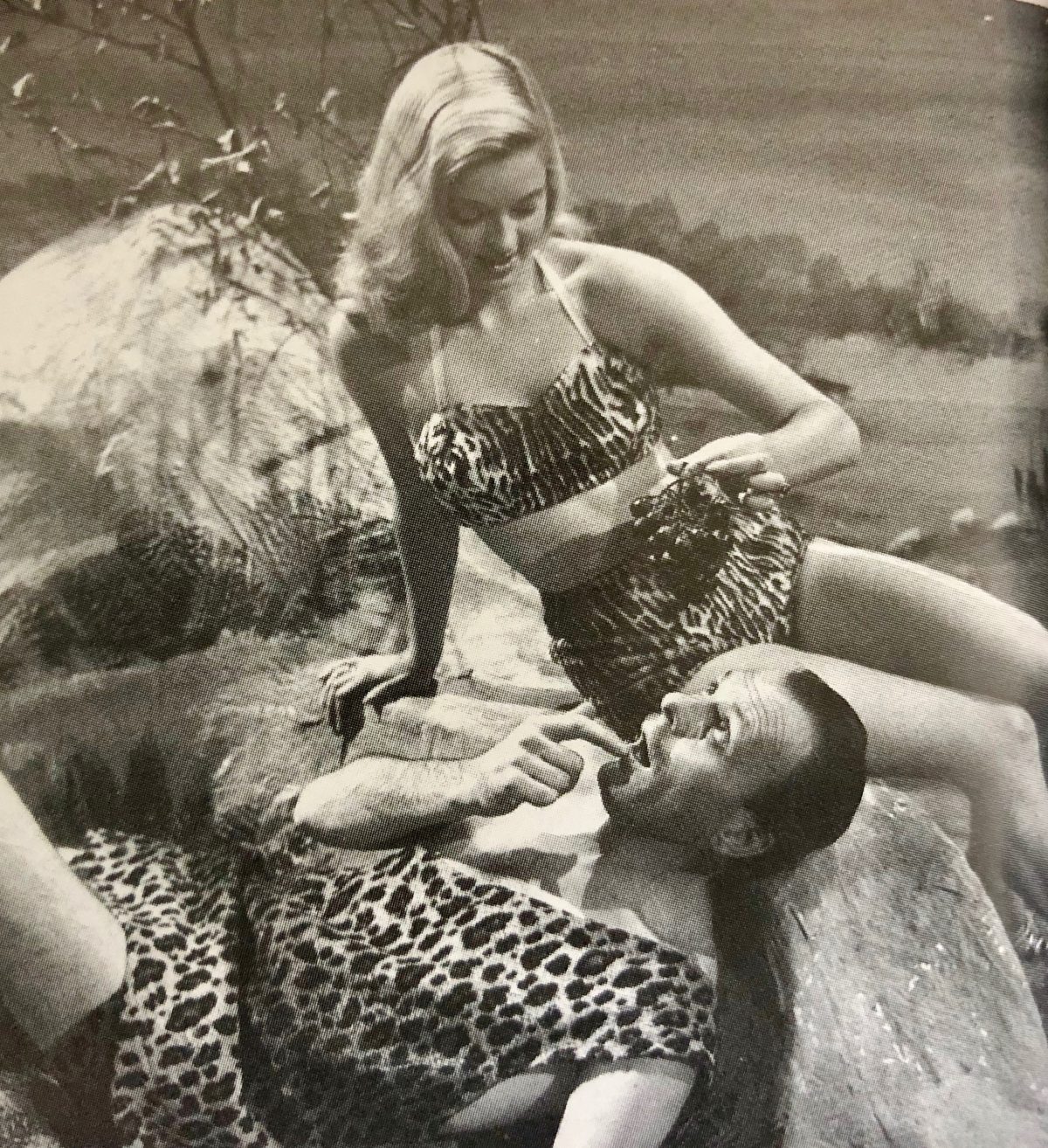

“I say: grapes – how perfectly jolly!’ Terry-Thomas as Tarzan and a young Diana Dors as Jane – 1951

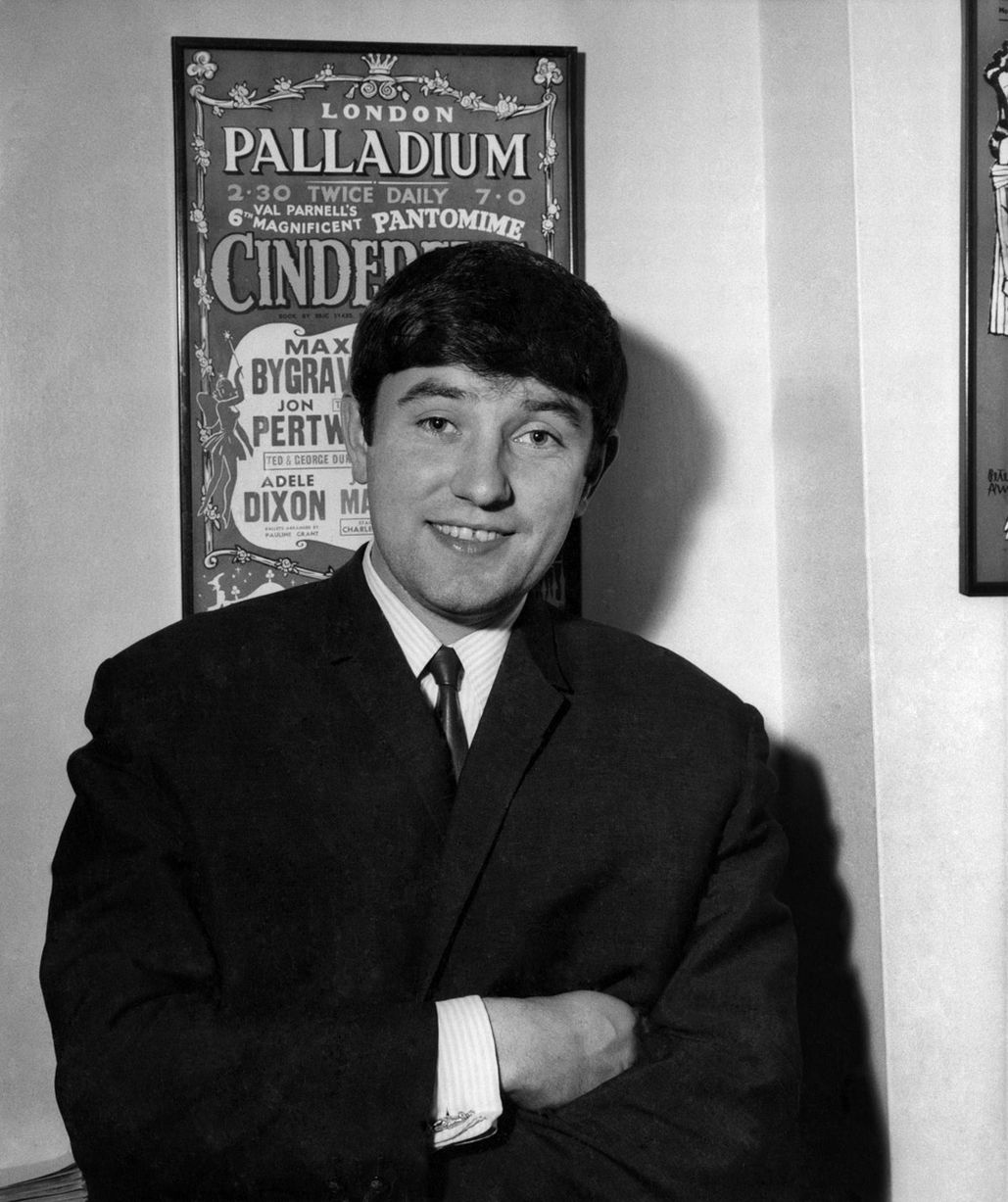

Terry-Thomas in Southport during a break from summer season in 1953

Lucky Jim in 1957

Terry-Thomas in How to Murder Your Wife (1965)

Terry-Thomas appeared in dozens of films, especially during the fifties and sixties. Unlike the comedian Sid Field, who died in 1950, T-T is still remembered and popular today with people who were not born at the height of his fame. T-T’s technique of underplaying many of his reactions also suited the big screen. He once explained that when filming a close-up in the 1956 film Private’s Progress, he was needed to show his character registering shock, fury and indignation; ‘I just looked into the camera and kept my mind blank. It’s a trick I’ve used often since. In this way, the audience does the work.’

In 1984 Terry-Thomas who had been living in Ibiza since 1968 in a villa he designed himself (‘I’m allergic to architects’), admitted in an interview that he had been told he had Parkinson’s Disease and only had a few years left to live. He had remarried in 1963 to a 21 year old called Belinda Cunningham, whom he had met on holiday in Majorca. In 1987 the couple could no longer afford to live in Spain and moved back to London. The couple lived in a series of rented properties, before ending up in a three-room, unfurnished charity flat, where they lived with financial assistance from the Actors’ Benevolent Fund.

Richard Briers was one of his first visitors to the flat, and was shocked by the change he saw: ‘He was just a mere shadow. A crippled, crushed, shadow. It was really bloody awful.’ On 9 April 1989, the actor Jack Douglas and Richard Hope-Hawkins organised a benefit concert for Terry-Thomas, after discovering he was living in virtual obscurity, poverty and ill health. The gala, held at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, ran for five hours, and featured 120 artists, with Phil Collins topping the bill, and Michael Caine as the gala chairman. The money raised allowed Terry-Thomas to move out of his charity flat and into Busbridge Hall nursing home in Godalming, Surrey. The man who personified the Englishman as an amiable bounder died there on 8 January 1990, at the age of 78.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.