We all of us like a recommendation. And if the reviewer is hymned gonzo journalist Hunter S. Thompson (July 18, 1937 – February 20, 2005), we listen up. (But take care: his daily routine is not to everyone’s tastes and could come with a health warning. Under 18s look away now.) Below are the writer’s 10 Best Albums of the 1960s, an era Thompson called “the rock age”. If the English art critic Walter Pater (4 August 1839 – 30 July 1894) was right when he noted in 1877 that “all art constantly aspires towards the condition of music”, this is a definitive list of top sounds.

The list is found in a letter Thompson wrote to Rolling Stone magazine editor John Lombardi in 1970. Lombardi notes: ‘Hunter thought great writers were marked by their “feeling of their time,” as musicians were – unlike journalists, New or old, who clumped along in serviceable slogs. “Reductionists!” he’d sometimes yell. “Simplifiers!”’

Thompson wrote to Lombardi:

“I resent your assumption that Music is Not My Bag because I’ve been arguing for the past few years that music is the New Literature, that Dylan is the 1960s’ answer to Hemingway, and that the main voice of the ’70s will be on records & videotape instead of books.

‘But by music I do’t mean the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band. If the Grateful Dead came to town, I’d beat my way in with a fucking tyre iron, if necessary, I think Working Men’s Dead is the heaviest thing since Highway 61 and Mr Tambourine Man (with the possible exception of The Stones’ least two albums… and the definite exception of Herbie Mann’s Memphis Underground, which may be the best album cut by anybody.) And that might make a good feature: some kind of poll of the best albums of the ’60s… or “Where it Was in the Rock Age”. Because the 60s are going to go down like a repeat, somehow, of the 1920s; the parallels are too gross for even historians to ignore.”

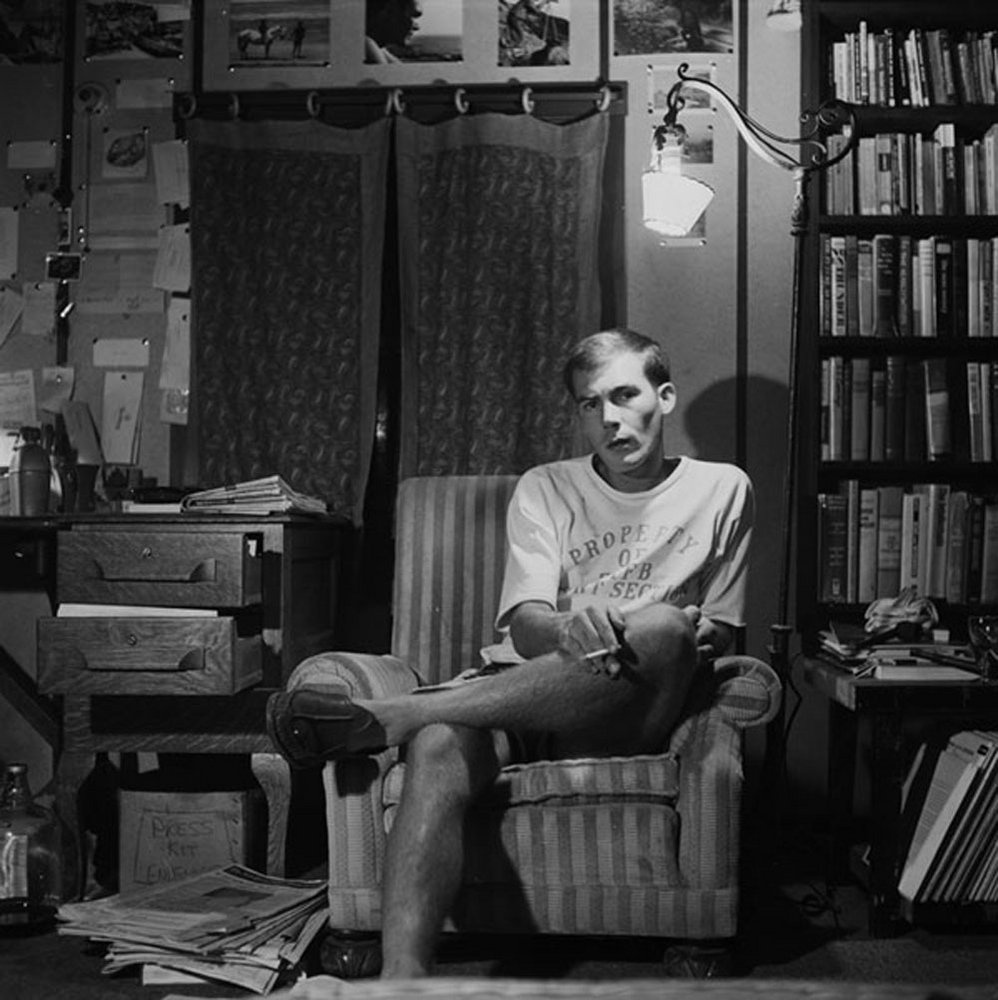

An outtake from the Bringing It All Back Home album cover shoot with Sally Grossman, Woodstock, January 1965. Photograph: Daniel Kramer/Courtesy of TaschenVia

But this isn’t all Thompson’s list, part of it was channeled through ‘Raoul Duke’, Hunter’s pseudonym, a hard-living “sports editor” existing in a perpetually exhilarated state of additive-fuelled speed. In the documentary film Fear and Loathing in Gonzovision, the title a riff on the writer’s book Fear And Loathing in Las Vegas, a tome penned under Duke’s byline, Thompson says:

“I’m never sure which one people want me to be [Thompson or Duke], and sometimes they conflict… I am living a normal life, but beside me is this myth, growing larger and getting more and more warped. When I get invited to Universities to speak, I’m not sure who they’re inviting, Duke or Thompson… I suppose that my plans are to figure out some new identity, kill off one life and start another.”

Should we take advice from Duke, Hunter or anyone, for that matter who became bigger in death than in life? In a letter dated April of 1958, Hunter S. Thompson wrote to his friend Hume Logan in response to a request for life advice, we read: “You ask advice: ah, what a very human and very dangerous thing to do! For to give advice to a man who asks what to do with his life implies something very close to egomania. To presume to point a man to the right and ultimate goal – to point with a trembling finger in the RIGHT direction is something only a fool would take upon himself.”

Take it or leave it, then. This Top 10 is personal. “Music has always been a matter of Energy to me, a question of Fuel,” Thompson wrote. “Sentimental people call it Inspiration, but what they really mean is Fuel. I have always needed Fuel. I am a serious consumer. On some nights I still believe that a car with the gas needle on empty can run about fifty more miles if you have the right music very loud on the radio.”

And here it is (via). Hunter S. Thompson’s Top 10: “So for whatever it’s worth–to either one of us, for that matter – here’s the list from Raoul Duke”:

- Herbie Mann’s 1969 Memphis Underground (“which may be the best album ever cut by anybody”)

- Bob Dylan’s 1965 Bringing It All Back Home

- Dylan’s 1965 Highway 61 Revisited

- The Grateful Dead’s 1970 Workingman’s Dead (“the heaviest thing since Highway 61 and ‘Mr. Tambourine Man'”)

- The Rolling Stones’ 1969 Let it Bleed

- Buffalo Springfield’s 1967 Buffalo Springfield

- Jefferson Airplane’s 1967 Surrealistic Pillow

- Roland Kirk’s “various albums”

- Miles Davis’s 1959 Sketches of Spain

- Sandy Bull’s 1965 Inventions

Now take it away. Herbie Mann (nee Herbert Jay Solomon (April 16, 1930 – July 1, 2003)). “Memphis Underground is a piece of musical alchemy, a marvelously intricate combination of the “Memphis sound” and jazz lyricism,” said Rolling Stone.

One song not on the list is Spirit in the Sky, a number by Norman Greenbaum, off of his 1969 album of the same name. This was one of the tunes played at Thompson’s memorial, in which his ashes were shot out of a cannon. They also played Bob Dylan’s Mister Tambourine Man, a song of which Thompson said:

This, to me, is the Hippy National Anthem. … To anyone who was part of that (post-beat) scene before the word “hippy” became a national publicity landmark (in 1966 and 1967), “Mr. Tambourine Man” is both an epitaph and a swan-song for the lifestyle and the instincts that led, eventually, to the hugely-advertised “hippy phenomenon.”

Can the typewriter be an instrument for making music?

Just months before Hunter committed suicide, he instructed his wife, Anita, to ship his red IBM Selectric II portable typewriter to Dylan. She balked: It was too precious to send away willy-nilly. But when Hunter died, she reconsidered. “He still has the harmonica you gave him that day in his drawer,” Anita wrote to Dylan. “In return, he wanted you to have his red Ibm Selectric II typewriter. He started a letter to accompany it on a few occasions, but got distracted by various deadlines, and didn’t want to send you a distracted letter. So anyway, here it is, and I am sorry the letter has to be from me, but it is important to him that you have the typewriter and use it for Chronicles. (I guess it would be Chronicles II now, right?)”

Clickety-clack. All art aspires to the condition of music.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.