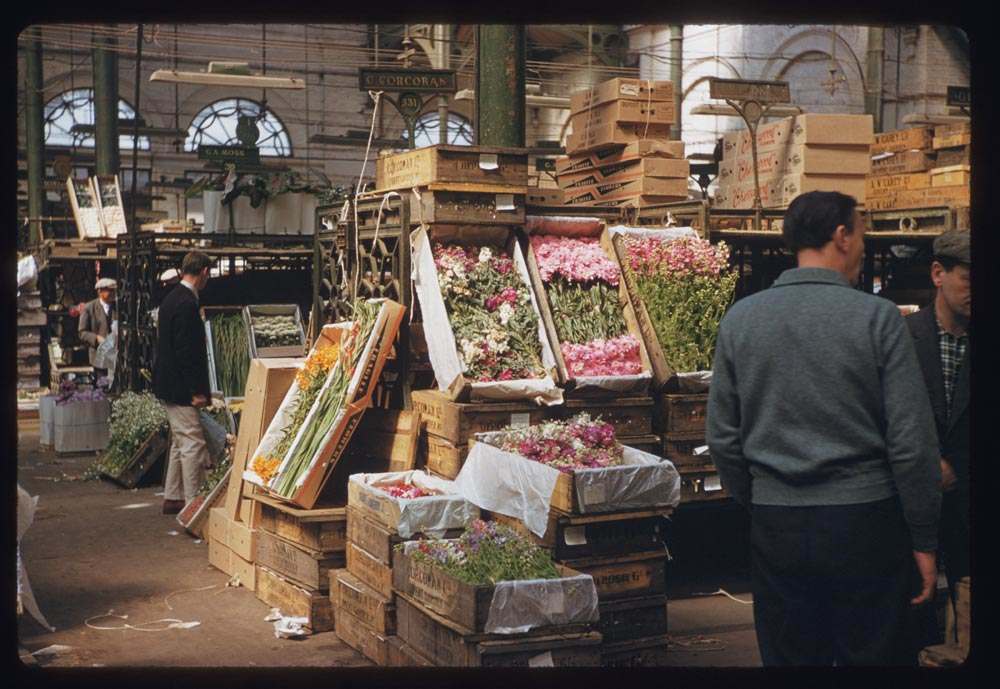

The London premiere for the film of My Fair Lady took place at the Warner cinema in Leicester Square on 21 January 1965. It couldn’t have been anything less than a glamorous occasion – Audrey Hepburn, Cecil Beaton, Rex Harrison (who came with Vivien Leigh) and even Jack Warner himself attended the show. The cinema is but a few hundred yards from Covent Garden, a location featured in the film (albeit a Hollywood studio-version) and which in the mid-sixties was still a functioning wholesale fruit, vegetable and flower market. A market that had been trading officially for almost 300 years ever since the Duke of Bedford in 1670 acquired from Charles II a charter allowing a fruit and vegetable market to take place every day except Sundays and Christmas day.

Rex Harrison and Audry Hepburn meet Princess Alexandra at the London premiere of My Fair Lady, January 1965.

The original musical and of course Shaw’s original Pygmalion from which it derived, purposely used an Edwardian Covent Garden to show the contrast of rich and poor Londoners rubbing shoulders in what was then a very poor area of inner-city London. Over half a century later in the sixties and seventies Covent Garden, as a place to live and work, was still a very run-down and shabby part of the West End, difficult as it is to imagine these days.

Presumably most of the councillors of the recently-formed Greater London Council, which had replaced the smaller London County Council the previous year, went along to see My Fair Lady – after all it was a very popular film. Not that it gave them any romantic notions of Covent Garden, for just two months after the film’s premiere the new Labour-run GLC published the Greater London Development Plan part of which proposed, astonishingly, but as was often the wont in those days, that over two-thirds of the historic Covent Garden area should be razed to the ground.

In his book The Changing Life of London, the late George Gardiner, a former journalist and Tory MP who with Norman Tebbit and Airey Neave would end up playing an important role in the election of Margaret Thatcher as Conservative Party leader (not that she thought much of Gardiner as he was offered not one ministerial or front-bench position), put across his view of the Covent Garden Development Scheme:

Any loss of nerve on this by the GLC in face of protest from a small section of London’s populace… when the opportunity has presented itself, will do down as a black day in London’s history. If the drift of population away from the centre is combined with a retreat from a policy of comprehensive redevelopment in favour of mere site development it is the next generation of Londoners who will be the losers and who will look back on our timid age with scorn.

Covent Garden market had essentially been nationalised in 1961 by the Conservative government when they created the Covent Garden Market Authority. Soon after there was a plan to move the overflowing market to Nine Elms in Battersea. In 1965/6, mindful that the fruit and vegetable market would soon be gone from the West End, three councils, the Labour-controlled GLC, the Tory-run City of Westminster and the Labour-run Borough of Camden, together with Bovis, the Prudential Assurance company and Taylor Woodrow worked together on the Covent Garden scheme. All of the parties were interested in just one thing – a totally comprehensive redevelopment of the 96 acres that made up the historic Covent Garden area.

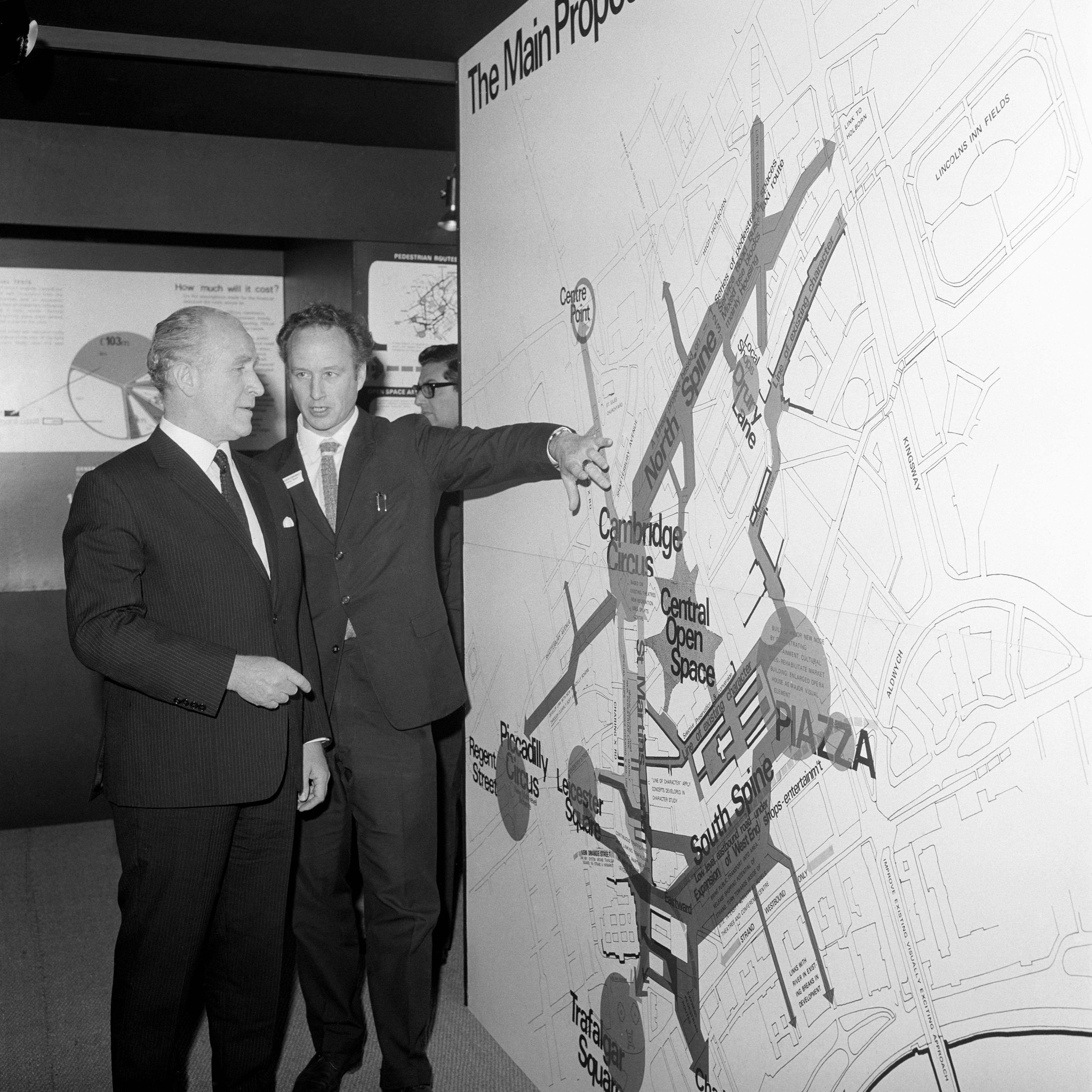

Gardiner wrote that when the initial draft plans was presented to the public “more than 3,500 people attended, and in fact, most of their comments were favourable”. The less favourable comments, however, were taken on board and a revised plan was approved by the GLC in 1970. What had changed, however, was that the three London councils, the GLC, Westminster and even Camden were now all Tory-controlled.

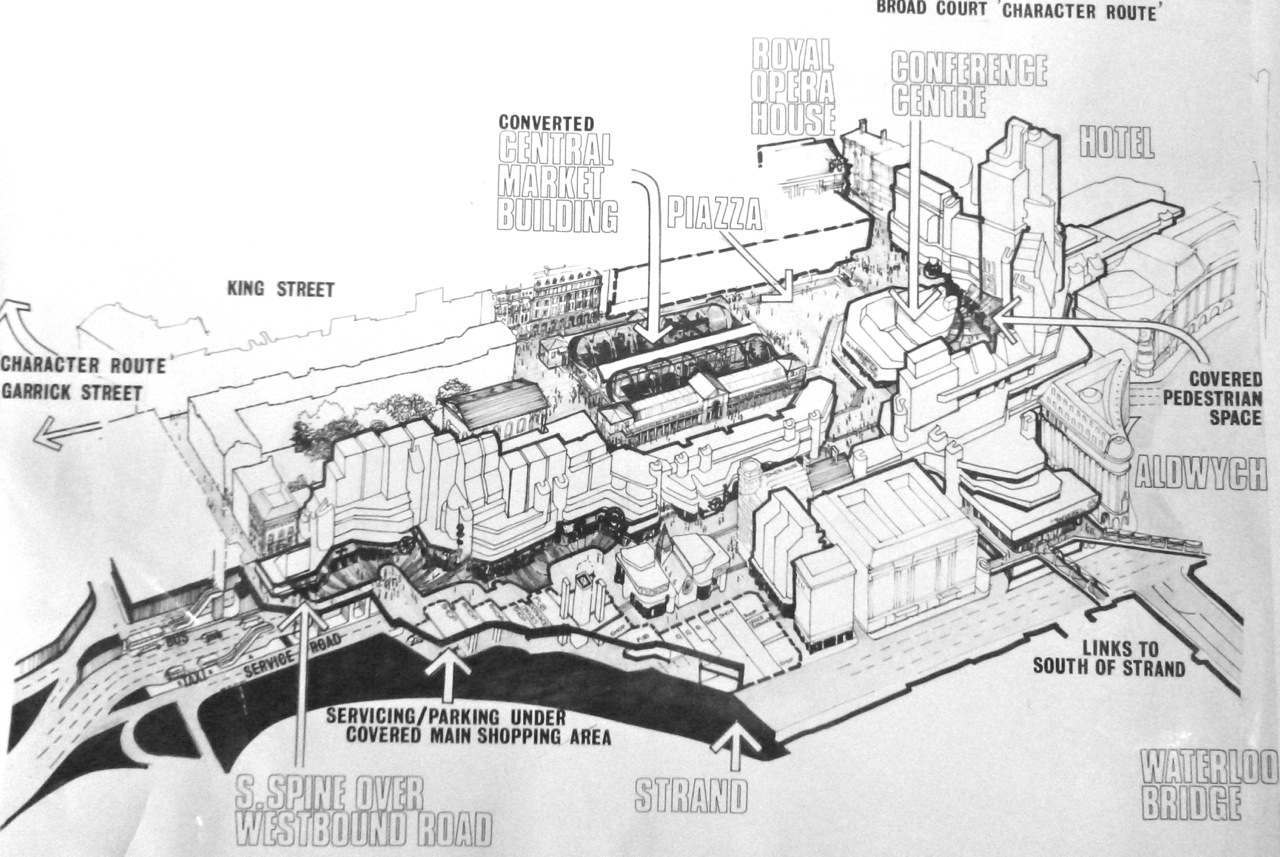

The Covent Garden redevelopment scheme covered 96 acres in an area bounded by the Strand, Aldwych, High Holborn, Shaftesbury Avenue and Charing Cross Road and it proposed the large-scale demolition of the great majority of the 18th and 19th century buildings around the historic old market. Gardiner, after rather excitedly describing the Covent Garden scheme as Central London’s biggest and most exciting redevelopment project since the Great Fire, wrote of the first phase of the plans which were intended to be built by 1975:

There would be three new schools in place of the two old ones, open recreational spaces and new shopping facilities, new hotels, and something London at present does not possess at all – an international conference centre. It would also include a new covered road, running roughly along the line of Maiden Lane, parallel with the Strand, carrying eastbound traffic while the Strand is made one-way westwards.

Horrifically, the international conference centre was designed to completely enclose Covent Garden’s famous Piazza – the Italian-style arcaded square built by Inigo Jones in the 1630s and which was commissioned by the fourth Earl of Bedford to encourage wealthy Londoners to move, to what was then, a semi-rural area. It has been said that Inigo Jones’ new and exciting designs for Covent Garden was, as far as London was concerned, the birthplace of modern town planning.

Meanwhile the second phase, planned for completion by 1980, involved the areas from Maiden Lane down to the Strand. The main feature of which was a new upper level pedestrian street that would link Trafalgar Square and Leicester Square with the Conference Centre. Beneath the raised walkway a brand new main road would run from Charing Cross Road to the Aldwych.

The third phase involved the area north of the piazza, sorry I mean the International Conference Centre, and would consist mostly of new housing, much of it built above smaller offices, the new schools, and other community facilities. In the same area, and as was the fad in those days, another concrete upper-level pedestrian street would run from east to west beneath which an internal service road linked to car parks was planned. At Cambridge Circus there would be a new recreation centre, with a swimming pool and squash courts and an office building one and a half times the size of Centre Point (infamously empty at the time with the developer, Harry Hyams was happy making money from the rising value of the property rather than letting it out). Covered pedestrian areas would lead to shops, existing theatres, restaurants and pubs, and over at the northern end of Drury Lane there would be a group of pedestrian squares at different levels, surrounded by shops and flats. This third phase of developments were were conceived to be completed by 1985.

In April 1971 a Covent Garden Community Association was formed to provide a unified protest from the local residents and small businesses affected by the radical redevelopment plans. By the time of the local inquiry into the plan in July 1971, Camden Borough Council, which by now had changed from Conservative to Labour control also became formal objectors to the plan it had helped work up three and five years previously.

On the 26th June Anthony Crosland, MP for Grimsby, and the shadow Environment minister made a passionate and influential speech in the commons attacking the damage to London made by the post-war developers:

I believe with passion that it is now time to call a halt. It is time to stop this piecemeal hacking away at our city. It is time to say to the GLC, to Westminster City Council, to Land Securities Investment Trust, to Town and City Properties, to the lot of them, “Gentlemen, we’ve had enough. We, the people of London, now propose to decide for ourselves what sort of city we want to live in.

He added:

If the minister takes the opposite view and allows these plans to go ahead, a very dangerous mood will develop amongst Londoners. There already is a mood of helpless resentment at the inability to stop these damned developments, and this may develop into a mood of active resentment. People will not have London continuously mutilated in this way for the sake of property development and the private motorist. They will not have an endless number of Centre Points and an endless number of uniform, monolithic, comprehensive redevelopments which break up communities and destroy the historic character of the city.

To the horror of many people who lived and worked in Covent Garden it initially looked like the GLC had won the redevelopment war when in July 1972 the plans were completely upheld by the inquiry inspector in his recommendation to the Conservative Secretary of State for the Environment Geoffrey Rippon.

The Countess of Dartmouth in 1972. She said about the Covent Garden plans: “I have felt increasingly that our proposals are out of date and out of tune with public opinion.”

Within a few weeks of the plans being approved the conservationist-minded Lady Dartmouth (who would later marry the Earl of Spencer and become the step-mother of Princess Diana) resigned from her post as chairwoman of the joint local authority committee who had been over-seeing the redevelopment plans. She had been affected by angry protesters who had at one point besieged her house and in her resignation letter she explained:

The theory of organising the sites so that offices, hotels and shops pay for housing, a park and a leisure centre is well-meaning; but no individual or bodies who represent the general public have supported us, and I have felt increasingly that our proposals are out of date and out of tune with public opinion, which fears that the area will become a faceless, concrete jungle…I am unable to work for a project in which I no longer believe, and which could do unnecessary and irreparable damage to an historic part of London.

The post-war consensus of modernising cities like London with the bull-dozer approach to redevelopment and traffic circulation was starting to fall apart. In January 1973, nearly eight years after the Covent Garden Redevelopment plan was originally made public and six months after the inquiry inspector had recommended the latest version, Geoffrey Rippon, while ostensibly approving the plan, effectively killed it. He had added 250 buildings to the list of those already protected because of historical and architectural merit which made comprehensive redevelopment in the Covent Garden area almost impossible.

In 1973 the GLC was recaptured by Labour and the new council told the developers and planners that they had to completely start again. Eventually the Covent Garden Community Association would have most of its demands met and nine out of ten of the key sites marked for demolition were saved in the final plans published in 1976.

Anthony Crosland MP who had made such a fine speech about London post-war development back in 1972 had written a book called ‘The Conservative Enemy’ ten years previously. In it he presciently summed up what had happened, and would happen, to so many city centres around the country:

Excited by speculative gain, the property developers furiously rebuild the urban centres with unplanned and æsthetically tawdry office blocks; so our cities become the just objects of world-wide pity and ridicule for their architectural mediocrity, commercial vulgarity, and lack of civic or historic pride.

In 1974 the Covent Garden fruit and vegetable market moved to Nine Elms in Battersea two years later than planned. It is still there today.

The Charles W Cushman pictures are courtesy of the Charles Cushman Collection: Indiana University Archives.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.