Housed at the Southworth Spanish Civil War Collection are over 600 drawings made during the Spanish Civil War by Spanish school children, both in Spain and in refugee centres in France. Made from pencil, crayon, ink, and watercolours, the drawings were collected by the Spanish Board of Education and the Carnegie Institute of Spain. Some were published for the American Friends Service Committee to raise funds for children’s relief efforts in Spain. The originals are held by the UC San Diego Library. We see many images of war, especially drawing of planes dropping bombs. Captions were written on the drawing verso.

American writer Aldous Huxley was asked to write on the drawings by the Spanish Child Welfare Association of America for the American Friends Service Committee, 1938.

He begins by taking on the role of art critic:

From an aesthetic and psychological point of view, the most startling thing about a collection of this kind is the fact that, when they are left to themselves, most children display astonishing artistic talents. (When they are interfered with and given “lessons in art,” they display little beyond docility and a chameleon-like power to imitate whatever models are set up for their admiration.)

Ministerio de Instrucción Pública, Colonia no 10, Elda (Alicante). [Mealtime by Carlos Ojeda].

These Spanish children, I repeat, have had to work under a technical handicap; but in spite of this handicap, how well, on the whole, they have acquitted themselves. There are combinations of pale pure colours that remind one of the harmonies one meets with in the tinted sketches of the eighteenth century. In other drawings, the tones are deep, the contrasts violent.

…

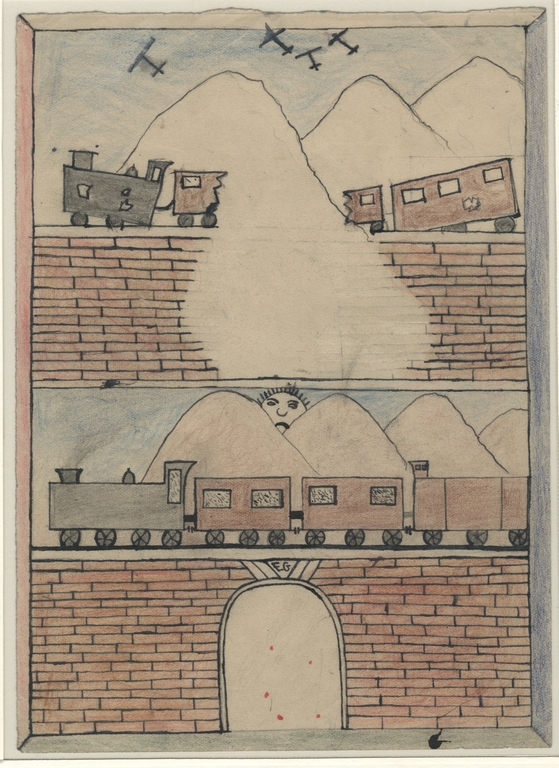

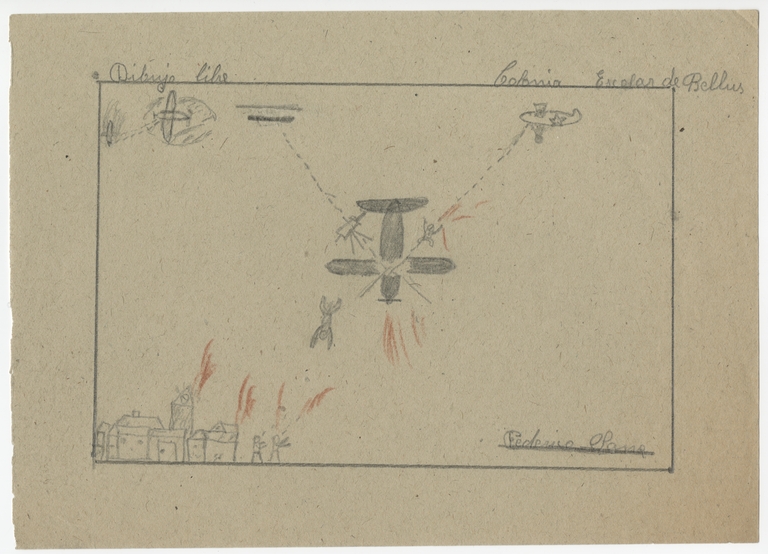

To a sense of colour children add a feeling for form and a remarkable capacity for decorative invention. Many of these pastoral landscapes and scenes of war are composed – all unwittingly, of course, and by instinct – according to the most severely elegant classical principles. Voids and masses are beautifully balanced about the central axis. Houses, trees, figures are placed exactly where the rule of the Golden Section demands that they should be placed. No deliberate essays in formal decoration are shown in this collection; but even in landscapes and scenes of war, the children’s feeling for pattern is constantly illustrated. For example, the bullets from the machine guns of the planes will be made visible by the child artist as interlacing chains of beads, so that a drawing of an air raid becomes not only a poignant scene of slaughter, but also and simultaneously a curious and original pattern of lines and circles.

Tomas Boscá Gomar, 13 years of age, Valencia, January 18, 1938

He turns to the themes and settings:

The pastoral scenes of life on the farm in time of peace, or in the temporary haven of the refugees camp, are often wonderfully expressive. Everything is shown and shown in the liveliest way. And the same is true of the scenes of war. The drawings illustrating bombardment from the air are painfully vivid and complete. The explosions, the panic rush to shelter, the bodies of the victims, the weeping mothers, upon whose faces the tears run down in bead-like chains hardly distinguishable from the rosaries of machine-gun bullets descending from the sky – these are portrayed again and again with a power of expression that evokes our admiration for the childish artists and our horror at the elaborate bestiality of modern war.

Luis Villar Baladrón, Bellús, 11 años [Luis Villar Baladrón, Bellús, age 11

Margarita Arnao Crespo, Colonia Escolar Colectiva La Torre Benejama (Alicante), años 12 [Margarita Arnao Crespo, Collective Student Camp The Tower Benejama (Alicante), age 12].

If we look at them with the eyes of historians and sociologists, we shall be struck at once by a horribly significant fact: the greater number of these drawings contain representations of aeroplanes. To the little boys and girls of Spain, the symbol of contemporary civilization, the one overwhelmingly significant fact in the world of today is the military plane – the plane that, when cities have anti-aircraft defenses, flies high and drops its load of fire and high explosives indiscriminately from the clouds; the plane that, when there is no defense, swoops low and turns its machine-guns on the panic-stricken men, women and children in the streets. For hundreds of thousands of children in Spain, as for millions of other children in China, the plane, with its bombs and its machine guns, is the thing that, in the world we live in and helped to make, is significant and important above all others. This is the dreadful fact to which the drawings in our collection bear unmistakable witness.

Ministerio de Instrucción Pública, Colonia no 10, Elda (Alicante). [A Spanish hero. E. Dieryma, age 15

Francisco Aguado Sanchez]. Physical Description 1 digital image Geographic Bellús–Valencia–Spain

Finally, he considers the future. What will come?

North of the Pyrenees and west of the Great Wall, the imagination of little boys and girls is still free (I am writing in the first days of September, 1938) to wander over the whole range of childish experience. The bombing plane has not yet forced itself upon their thoughts and emotions, has not yet forced itself upon their thoughts and emotions, has not yet stamped its image upon their creative fancy. Will it be possible to spare them the experiences to which the children of Spain and China have been subjected?

He addresses his own question:

The most that individual men and women of good will can do is to work on behalf of some general solution of the problem of large-scale violence and, meanwhile to succour those who, like the child artists of this exhibition, have been made the victims of the world’s collective crime and madness.

Ministerio de Instrucción Pública, Colonia no 10, Elda (Alicante). [Hitler [and] Mussolini- Two big foxes [or knaves] that run away from the war. A. Guisánchez, age 14

Residencia Infantil No 1, Onteniente. Juan José Martinez 15 años [Juan José Martinez age 15].

Ministerio de Instrucción Pública, Colonia no 10, Elda (Alicante). [Two good friends, Health, Long live the Republic, Paco Lariego].

Ministerio de Instrucción Pública, Colonia no 10, Elda (Alicante). [Miaja A symbol of Spanish liberties. Enrique Dieryma].

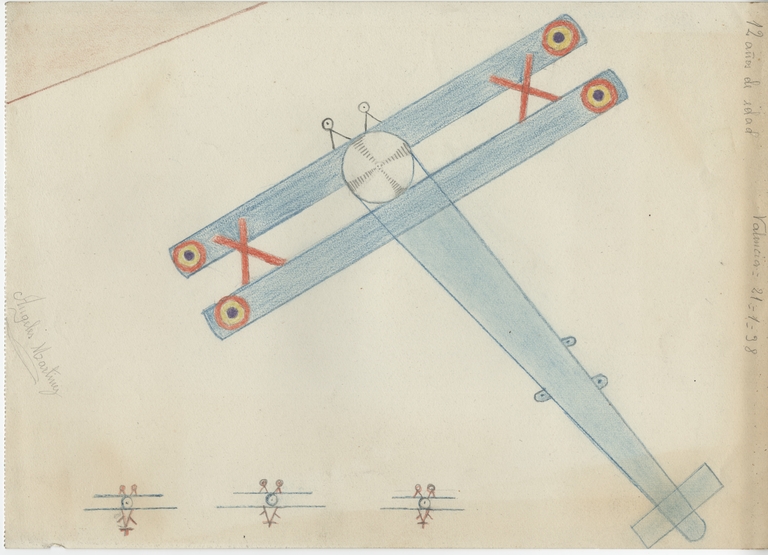

12 years of age, Valencia — 1-21-38, Angeles Martinez

Above on the Verso: Este dibujo he hecho para representar nuestra vida en la Colonia, ahí vemos unos niños jugando al balón, otro que soy yo tocando la campana por ya es hora de comer y una encargada llevando el caldero de la comida. Angeles Arnáíz (niña), 14 años, Colonia Infantil de Bayona (Francia) [This drawing I have done to show our life in the Camp, here we see some children playing ball, another which is me ringing the bell because it is lunchtime and another undertaking carrying the pot with the food. Angeles Arnáíz (girl), age 14, Children’s Camp of Bayonne (France)].

Damian Casas Mares of 9 years]

Residencia Infantil no 6 San Juan Alicante, Olegario López 11 años [Children’s Residence #6 San Juan Alicante, Olegario López age 11].

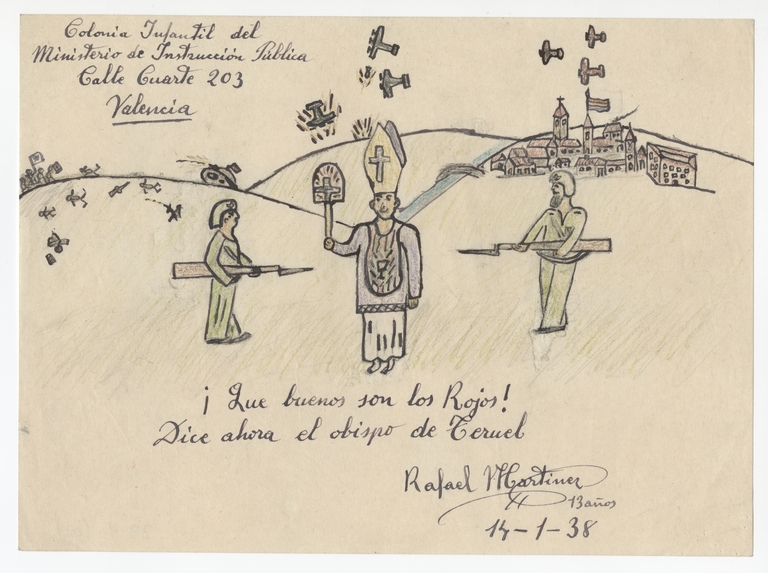

Children’s Camp of the Ministry of Public Instruction, 203 Cuarte Street, Valencia, The Reds are so good! now says the bishop of Teruel. Rafael Martinez, age 13, 1-14-38

Escuela Nacional de Niñas No 45-B, Madrid. [conejera [?], José Asenjo]

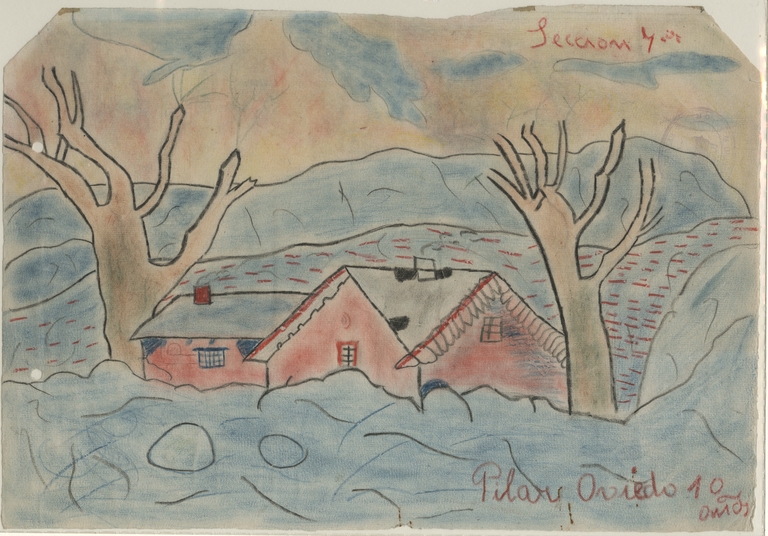

10 exhibited at the Worcester Art Museum and reproduced in the Worcester Telegram by Pila, Oviedo

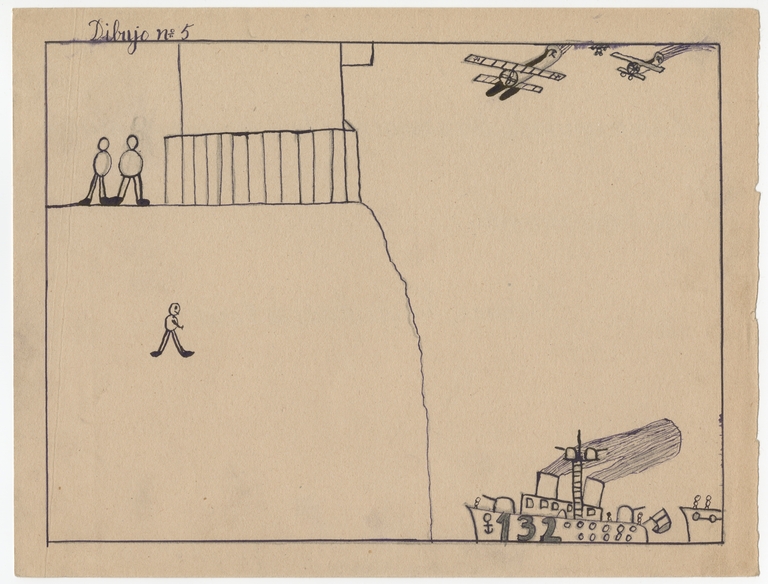

José Bernabe, age 11, Madrid (Spanish Center), Perpignan. An aerial bombing of the streets of Madrid

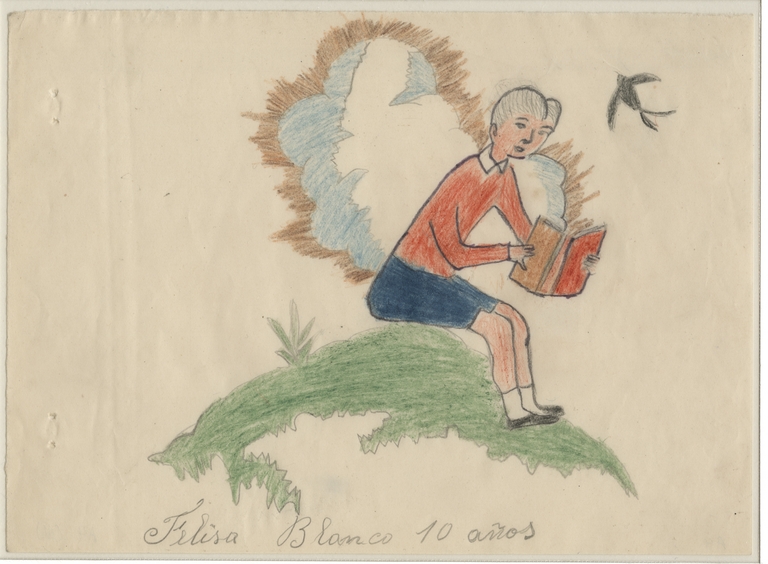

Felisa Blanco age 10, Madrid

Buñol on January 15, 1938, Age 14 years, Valencia

Peace:War. Pedro García Alicante

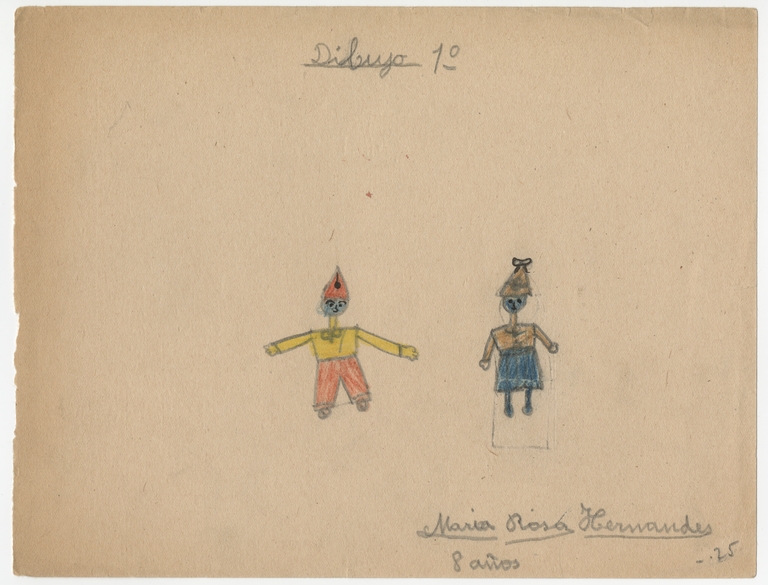

Maria Rosa Hernandes, age 8, Cerbere Camp, France

Esta escena representa un bombardeo en mi pueblo, Port-Bou. Ma Dolores Sanz, 13 años

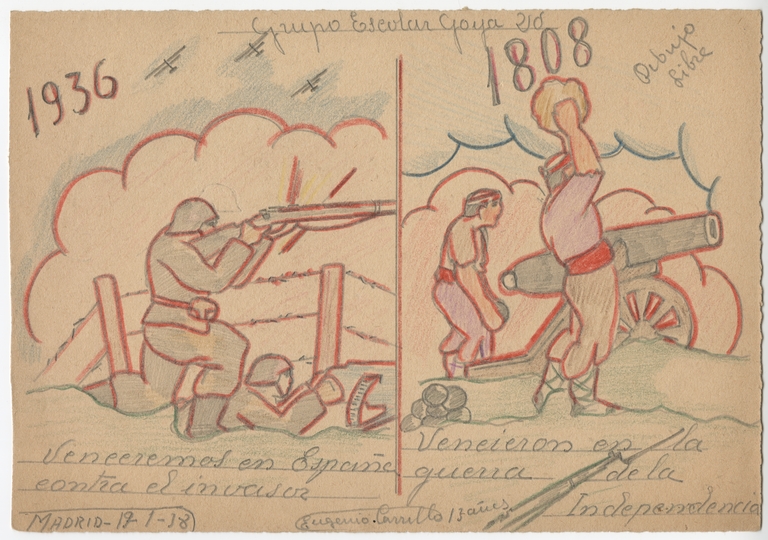

They prevailed in the war of Independence. Madrid – 1-19-38, Eugenio Carrillo

Colonia no 10, Elda (Alicante). José Caballero Moro

Francisco Aguado Sanchez]. Physical Description 1 digital image Geographic Bellús–Valencia–Spain

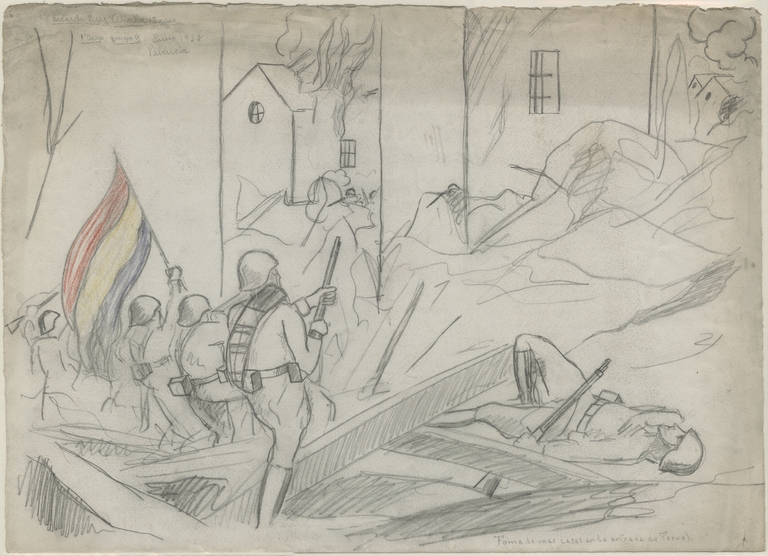

Ricardo Perez Villalba age 13, 1st year group B, January 1938, Valencia. Taking some of the houses at the entrance of Teruel

Residencias Infantiles, Colonia de El Alba, Onteniente.

Escuela Nacional Graduada de Niños de la Florida, Madrid. [Winter Felix Fernández (12 años)].

Student Camp at Bellus, Federico Sanz

Refuge – in case of bombings

Elda (Alicante). Lenin. Pedro García García

Ministerio de Instrucción Pública, Colonia no 10, Elda (Alicante). [A soldier of the new Spanish army. A. Guisánchez, age 14. Long live the Republic! Forever!!

Ministerio de Instrucción Pública, Colonia no 10, Elda (Alicante). [Felix Alareos. What the worker’s international should ask for. Trotsky, Hitler and Mussolini, the fatidical trio of death, walk towards…].

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.