”It was like some crazy-art world marriage and they were the odd couple. The relationship was symbiotic. Jean-Michel thought he needed Andy’s fame, and Andy thought he needed Jean-Michel’s new blood. Jean Michel gave Andy a rebellious image again.”

— Andy Warhol’s longtime studio assistant Ronny Cutrone in Warhol: The Biography by Victor Bockris.

Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988) and Andy Warhol (1928-1987) worked well together, their output fast and prolific, producing around 160 paintings in tandem. Acolytes of one another’s era-defining talents, Basquiat admired Warhol’s position in the world as a driving force in the language of pop culture. Warhol loved Basquiat’ youth, radiance and perspective, which renewed his own love of painting, getting him, as he put it, “into painting different”.

Keith Haring (1958-1990), who witnessed their friendship and collaboration, spoke of their “conversation occurring through painting, instead of words”, of two artists merging to create a “third distinctive and unique mind”. Eventually, the monied, knowing art world, having embraced Basquiat, chewed him up and regurgitated him on the New York’s pavement, full of drugs and dead at 27.

As the young Basquiat, who started out daubing graffiti on New York city’s walls where the rich might notice him, might have put it, SAMO: “same old shit.” But Warhol was different. Like Basquiat, he took in scraps of culture and information from a myriad sources and spilled them onto the canvas, to make us look again and the high-minded art world come down to their level.

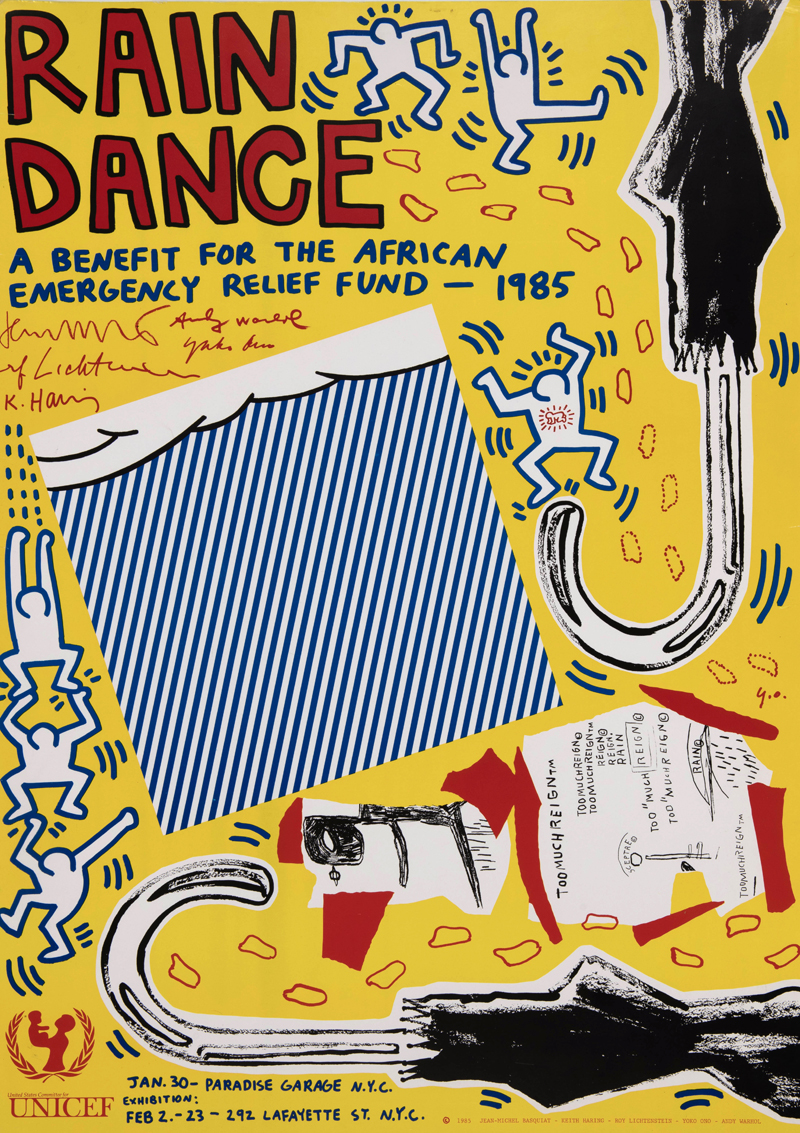

Keith Haring, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, Yoko Ono, Rain Dance: A Benefit for the African Emergency Relief Fund, Large Poster, Exhibition at 292 Lafayette; Benefit Party at Paradise Garage, 1985

Jean-Michel Basquiat Brown Spots (Portrait of Andy Warhol as a Banana), 1984 / Brown Spots (Portrait of Andy Warhol as a Banana), 1984, Private collection. Courtesy Galerie Bruno Bischofberger, Männedorf-Zurich, Switzerland

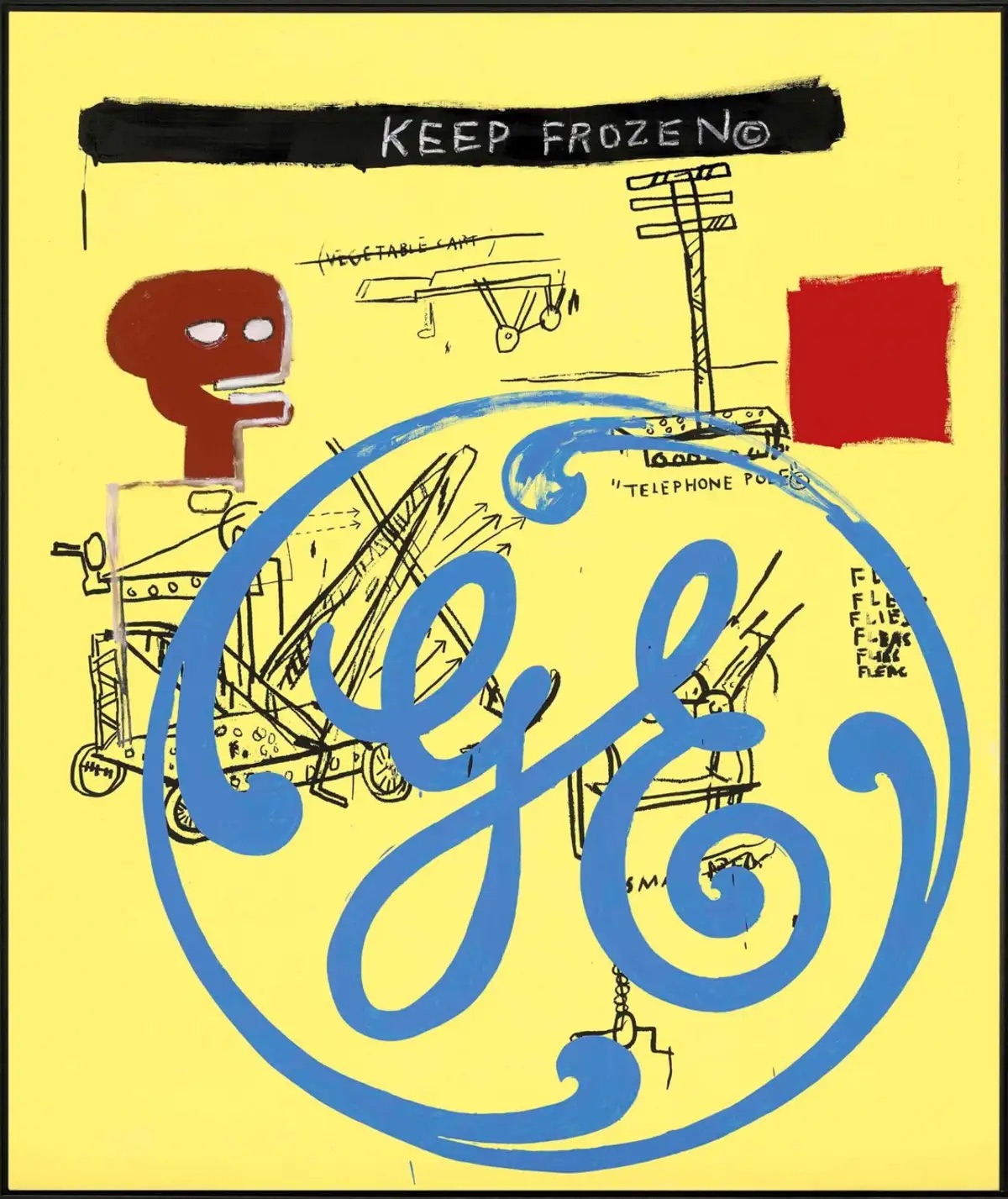

They duo blurred the line between fine art and mass visual communication and the compositions have large expressive areas of bright, complementary colours. As Basquiat noted:

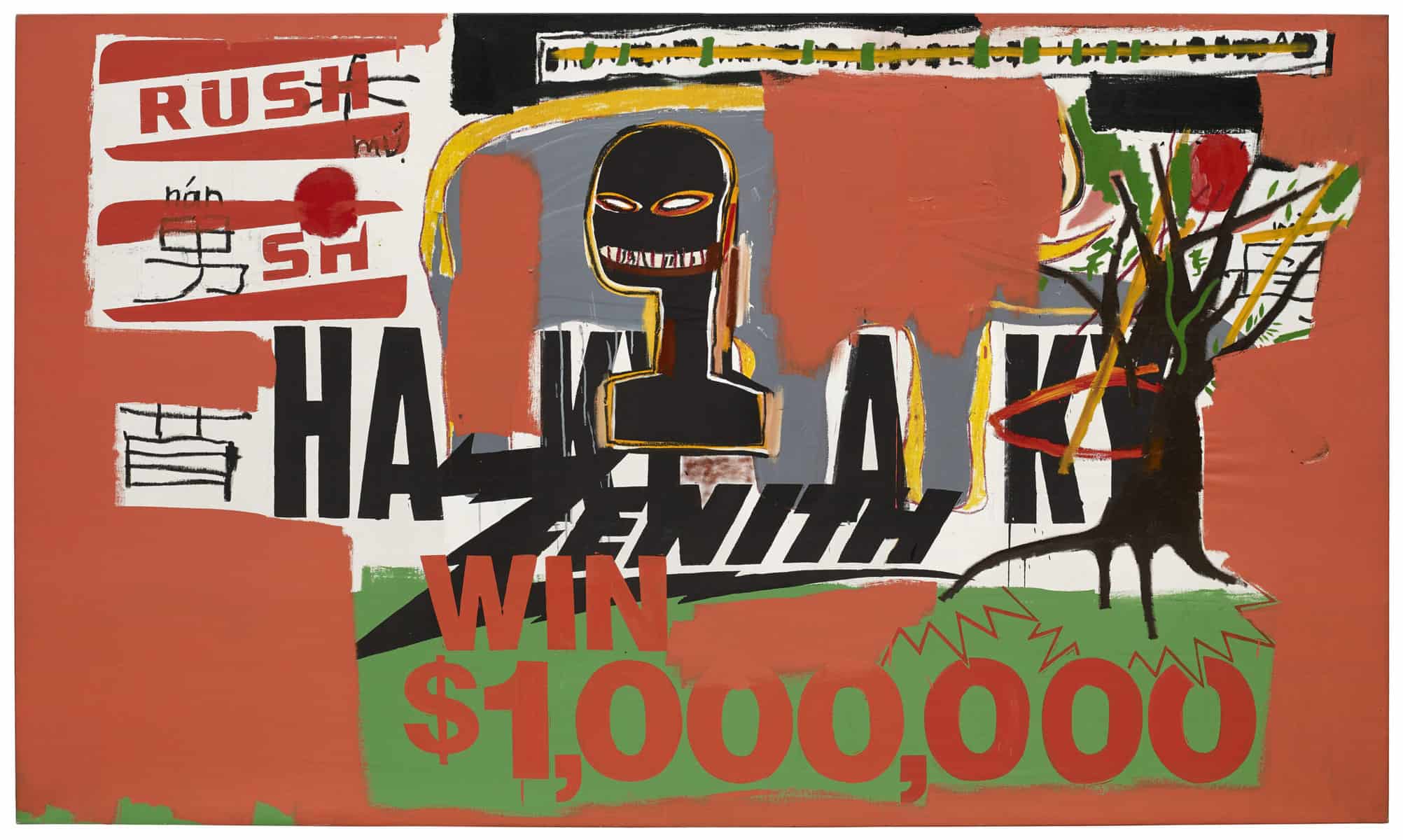

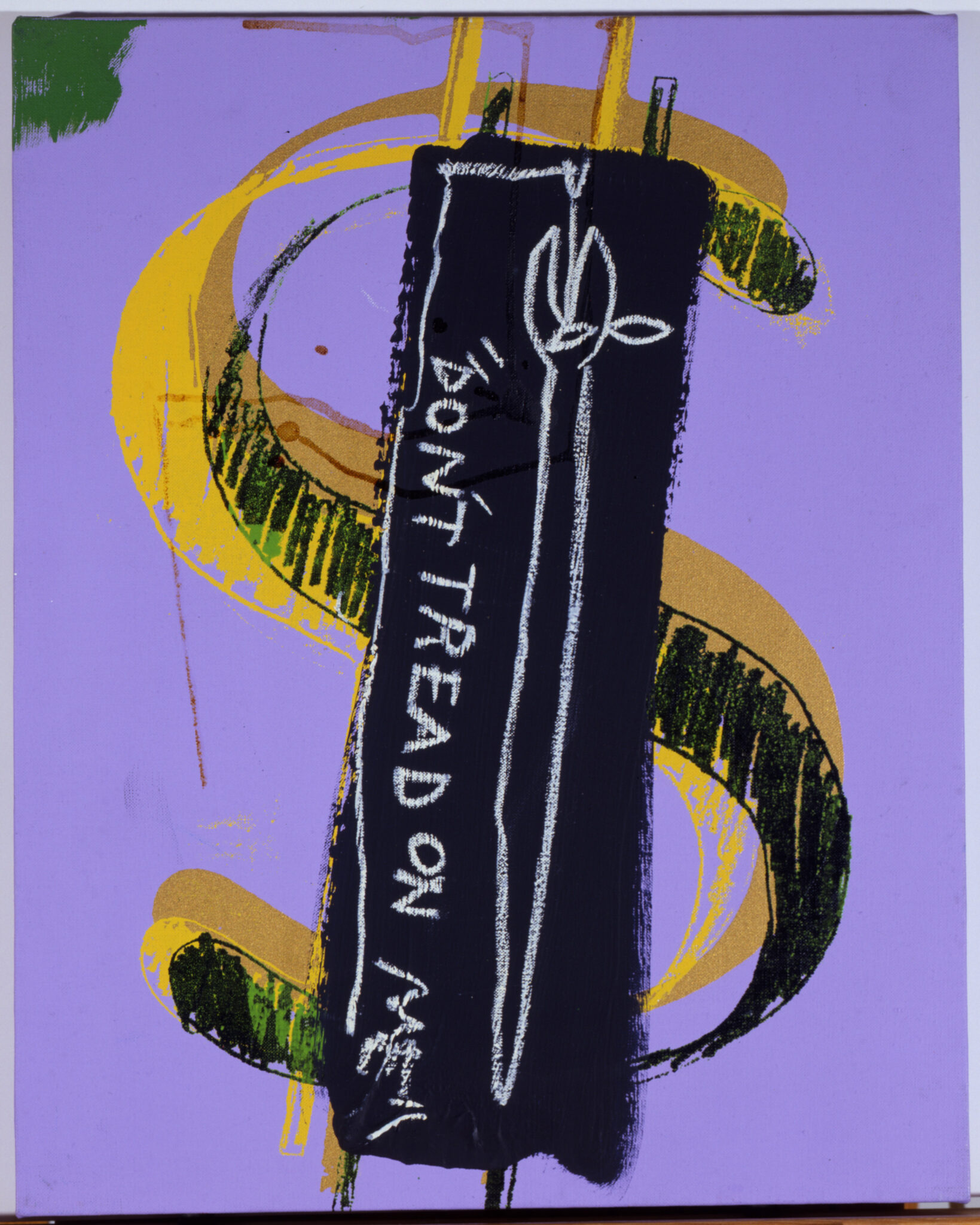

“Andy would start one (painting) and put something very recognisable on it, or a product logo, and I would sort of deface it. Then I would try to get him to work some more on it, I would try to get him to do at least two things.”

Image © Christie’s : Keep Frozen (General Electric) © Andy Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat 1985

German art dealer Bruno Bischofberger explains how the collaboration came to happen and his own key part in setting it up:

In the autumn of 1982 I brought Jean-Michel to Andy Warhol in the Factory and this is how they really got to know each other. I had a firm agreement with Warhol that I could propose younger artists which I found interesting for an article in Interview Magazine, which we had founded together in 1969. Warhol also let me decide which young artists I could bring with me to the Factory to have a portrait done, in exchange for which they could swap one of their works. Warhol trusted my judgement and it was of no consequence that the works that he received in exchange were often worth much less than his portraits. In this way Andy established a relationship with the generation of younger artists. When I told him that I would bring Jean-Michel Basquiat for a portrait session and the usual buffet lunch at the Factory on Union Square the next day he seemed rather surprised and asked me„ Do you really think that Basquiat is such an important artist?“ Warhol was not familiar with Basquiat‘s new work and told me that he remembered having met the artist on one or two occasions, on both of which Warhol had felt him to be too forward. Basquiat had been trying to get to know Warhol and had offered him his street sale art, small drawings on paper that Warhol had been very sceptical of.

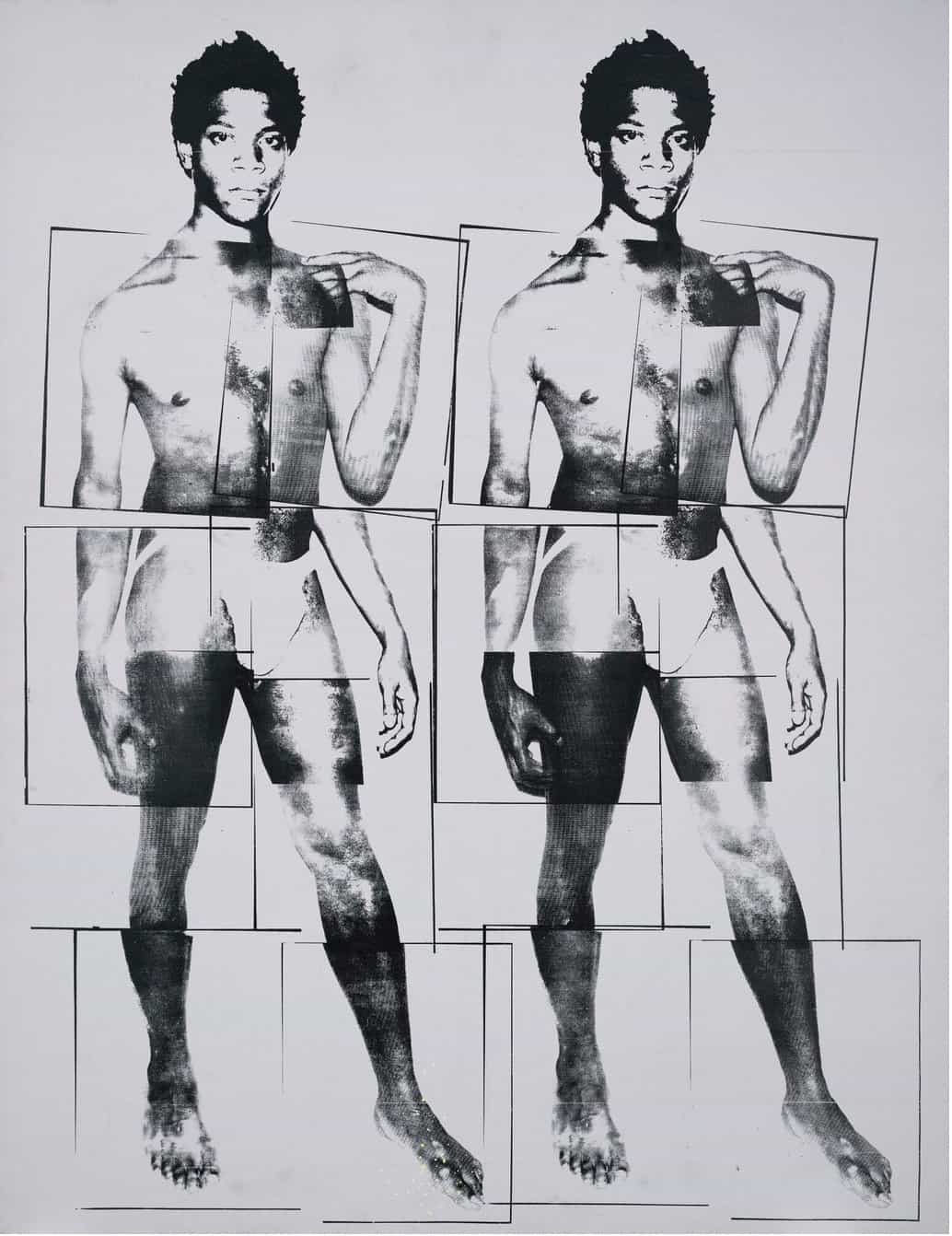

Warhol photographed Basquiat with his special Polaroid portrait camera. Jean-Michel asked Warhol whether he could also take a photo of him, took some shots and then asked me to take some photos of him and Warhol together. We then wanted to go next door to have the customary cold buffet lunch. Basquiat did not want to stay and said goodbye. We had hardly finished lunch, one, at most one and half an hour later, when Basquiat‘s assistant appeared with a 150 x 150 cm (60 x 60“) work on canvas, still completely wet, a double portrait depicting Warhol and Basquiat: Andy on the left in his typical pose resting his chin on his hand, and Basquiat on the right with the wild hair that he had at the time. The painting was titled Dos Cabezas. The assistant had run the ten to fifteen blocks from Basquiat‘s studio on Crosby Street to the Factory on Union Square with the painting in his hands because it wouldn‘t fit into a taxi.

Jean-Michel Basquiat et Andy Warhol, Win $1,000,000, 1984 Acrylic and oilstick on canvas 170 × 288,5 cm, Bischofberger Collection, Männedorf-Zurich, Switzerland

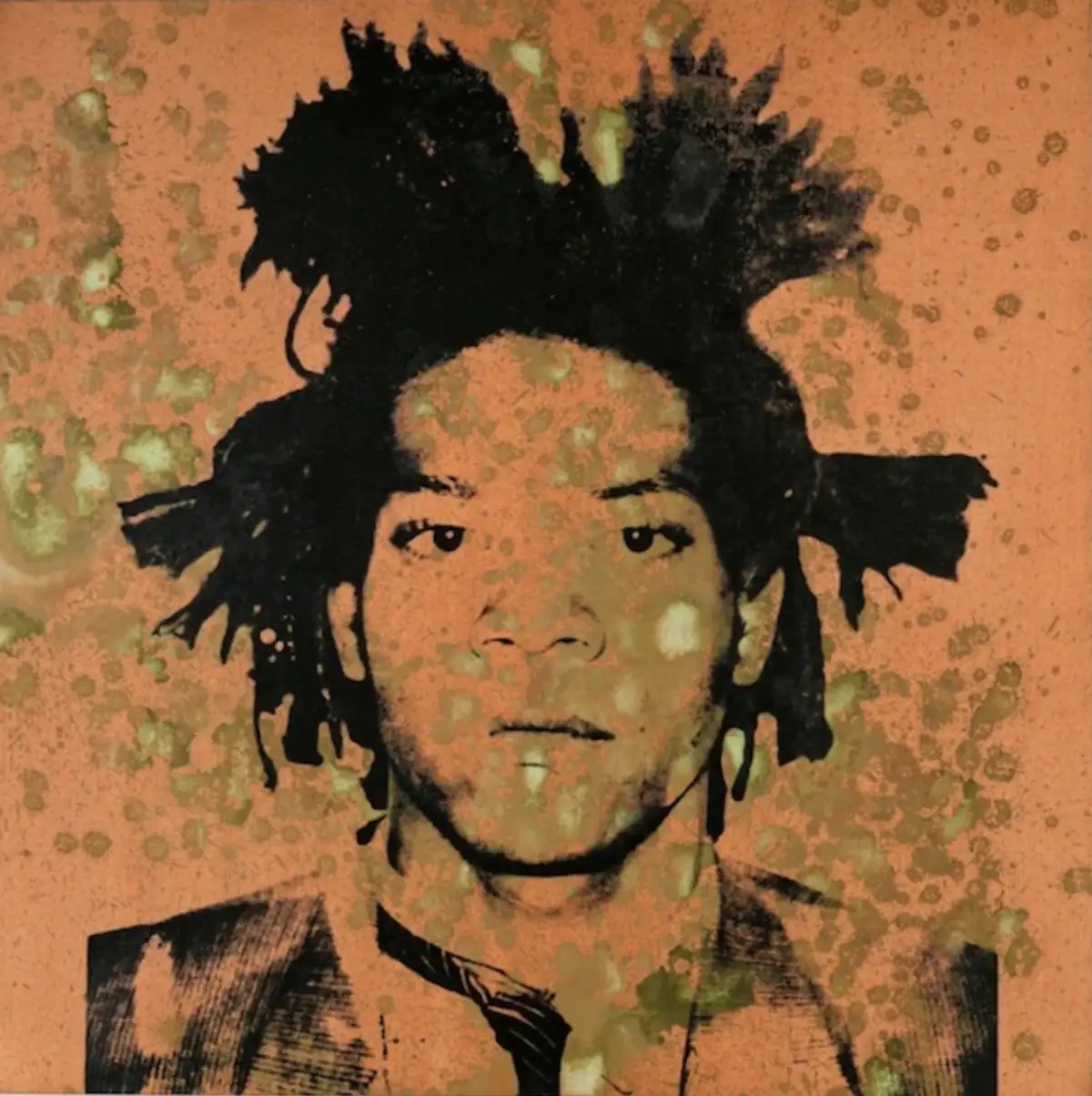

All visitors and employees at the Factory flocked around to see the painting, which was admired by all. Most astonished of all was Andy who said: “I‘m really jealous – he is faster than me.“ Soon thereafter Warhol made a portrait of Basquiat on several equally large canvases: Basquiat sporting his wild hairdo, silkscreened on the background of the “oxidation“ type, the same as the Oxidation or Piss Paintings of 1978. Basquiat subsequently painted another two portraits of Warhol. One in 1984 entitled Brown Spots, which depicts Andy as a banana, and the other in 1984-85 which shows Warhol with glasses and large white wig working out with a barbell in each hand.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Andy Warhol, Dollar Sign / Don’t Tread on Me, 1984-1985 Acrylic, silkscreen ink, and oilstick on linen 51 x 41 cm The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

Basquiat and I soon started to speak of Francesco Clemente as the third artist for the collaborations project and we decided together to invite him to join in, after having pondered Julian Schnabel as an alternative. First, of course, we wanted to know whether Warhol would agree to do the project.

Jean-Michel knew and respected Clemente, whose studio was only two blocks away from Jean-Michels. In the following years he became great friends with him and his wife Alba. He also knew Schnabel well, and for quite some time, and was very impressed by his work and his success. Basquiat decided not to approach Schnabel with the collaboration project because, as he explained to me, he felt that an artist like Schnabel, with his strong, dominating personality, could not have prevented himself from influencing or commenting upon the work of the other collaborating artists. Basquiat, as a black in New York, was over-sensitive to other artist‘s comments on his work. He told me that he was once insulted, in my opinion wrongly, when Schnabel, as a response to the question how he found a work of Basquiats which both were looking at, gave what Basquiat considered to be a too critical answer, but which was surely meant by Julian to be no more than a constructive suggestion.

Andy Warhol Portrait of Jean-Michel Basquiat as David, 1984, Synthetic polymer and silkscreen ink on canvas 228.6 × 176.5 cm, Collection of Norman and Irma Braman

Clemente had, in the summer of 1983, painted a group of twelve large paintings in Skowhegan, Maine, which I was able to purchase from him and which are also a sort of collaboration. He stretched fragments of painted theatre backdrops made of cloth on stretchers and added his own inventions to those already there. Schnabel had also, early on his career, painted on surfaces that had a clearly defined structure, in a sort of collaboration. In 1986 he painted a series of Japanese Kabuki theatre backdrops, and Enzo Cucchi also painted on four Italian theatre backdrops in 1987.

To get the most spontaneous work into the collaborations I suggested to Basquiat that every artist should, without conferring with the others about iconography, style, size, technique, etc., independently start the paintings, of course in the knowledge that two further artists would be working on the same canvas, and that enough mental and physical space should be left to accommodate them. I further suggested to him that each artist send one half of the started collaborations to each of the other artists and the works then be passed on to the remaining artist whose work was still missing. Basquiat liked my proposal and agreed.

Jean-Michel Basquiat and Andy Warhol, 6,99,1984. Courtesy of Nicola Erni Collection. © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by ADAGP, Paris 2023. © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat Licensed by Artestar, New York.

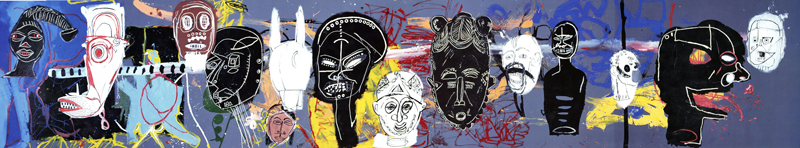

Jean-Michel Basquiat & Andy Warhol, “African Masks” (c. 1984-1985), Rollout Poster with Tube for the Exhibition Collaboration Paintings, Gagosian Gallery, 2002

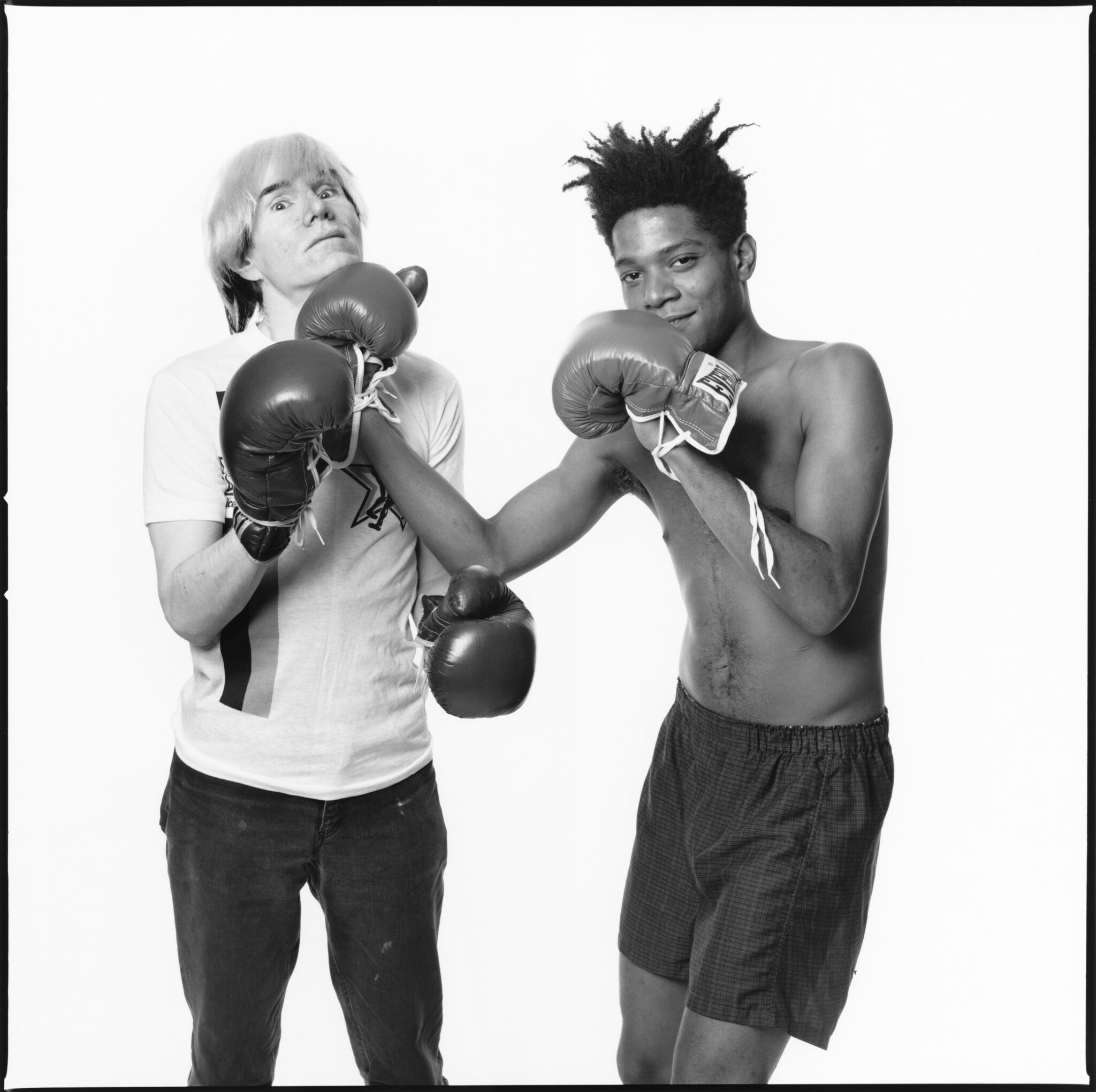

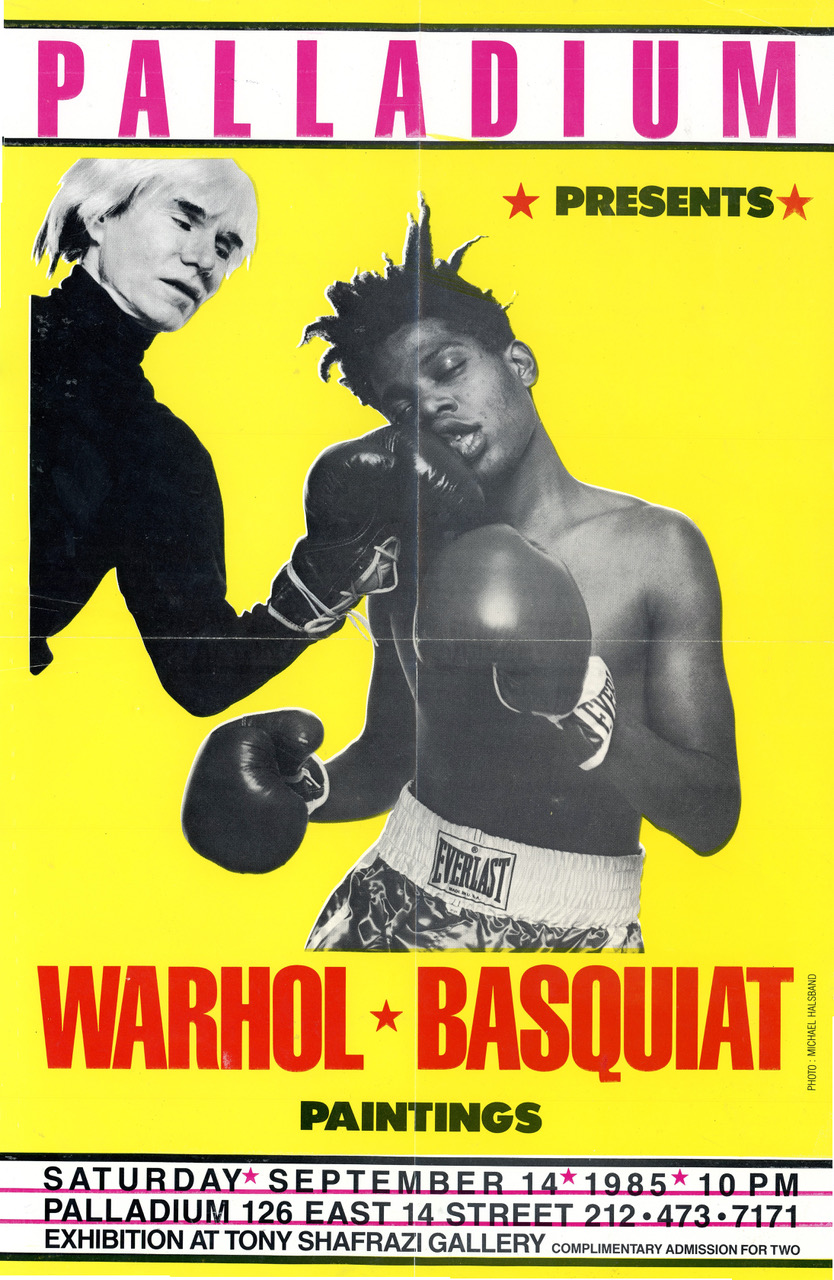

Andy Warhol, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Photo by Michael Halsband, Poster for the Paintings After-Party at the Palladium, 1985

The Portrait of Basquiat by Warhol, fruition of their partnership, that sold for $34,700,000. (Image © Christie’s : Jean-Michel Basquiat © Andy Warhol 1982)

Pictures via: The fabulous Gallery 98, and the exhibition Basquiat x Warhol. Painting 4 Hands at Fondation Louis Vuitton.

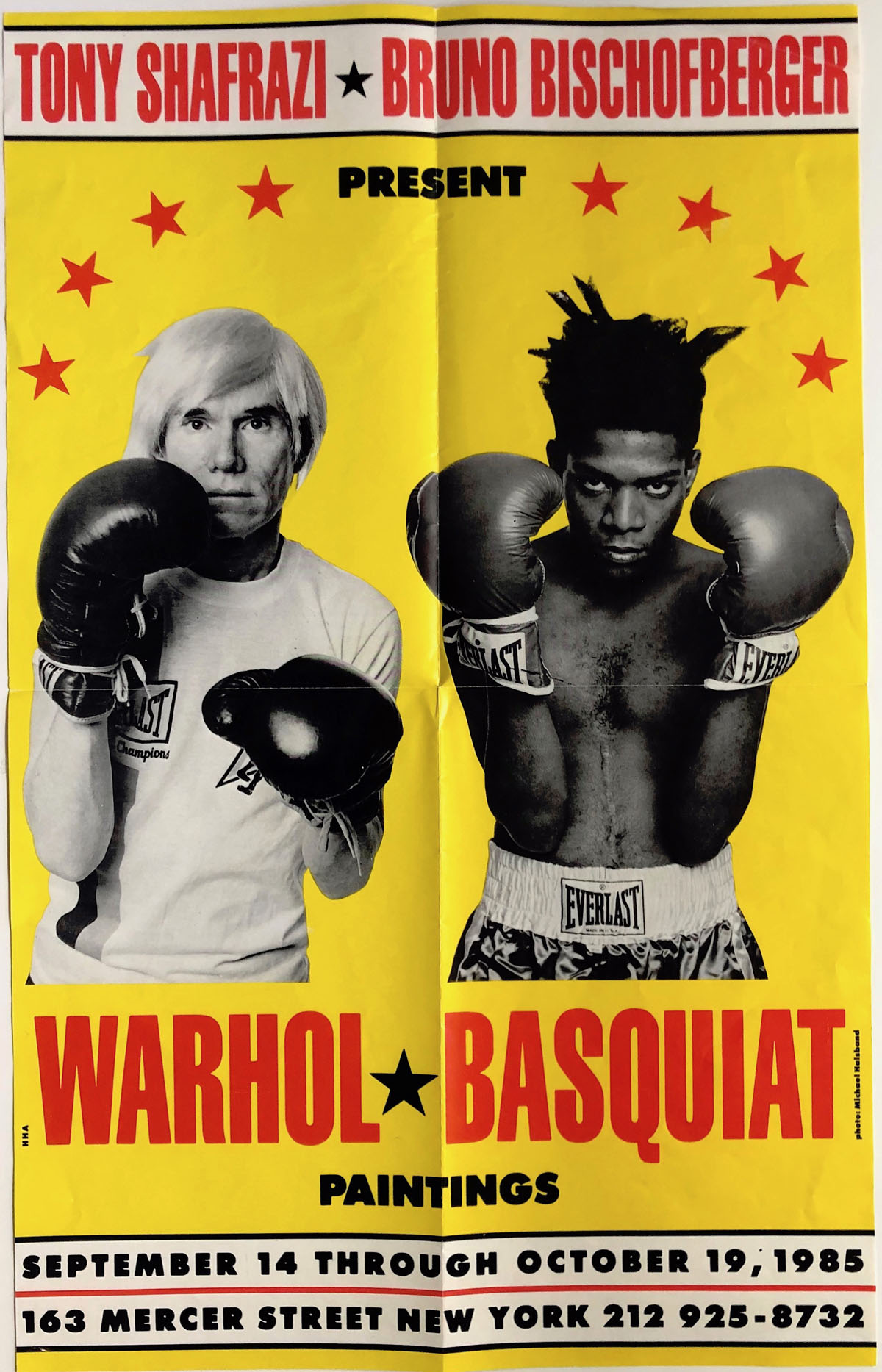

Lead Image: Tony Shafrazi Gallery, Warhol, Basquiat, Paintings, Poster, September – October 1985

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.