“Men are just accessories, like hats and gloves”

– Helmut Newton

Born in Weimar Germany in 1920, Helmut Newton, from an early age, displayed “a fascination for women,” Ryan Lattanzio writes at IndieWire, which the fashion photographer himself describes in new documentary Helmut Newton: The Bad and the Beautiful “through several amusing stories” that sound like early episodes of sexual assault. It’s hardly surprising Newton drew the ire of feminist critics like Susan Sontag, who takes him to task in a TV interview clip from the 70s.

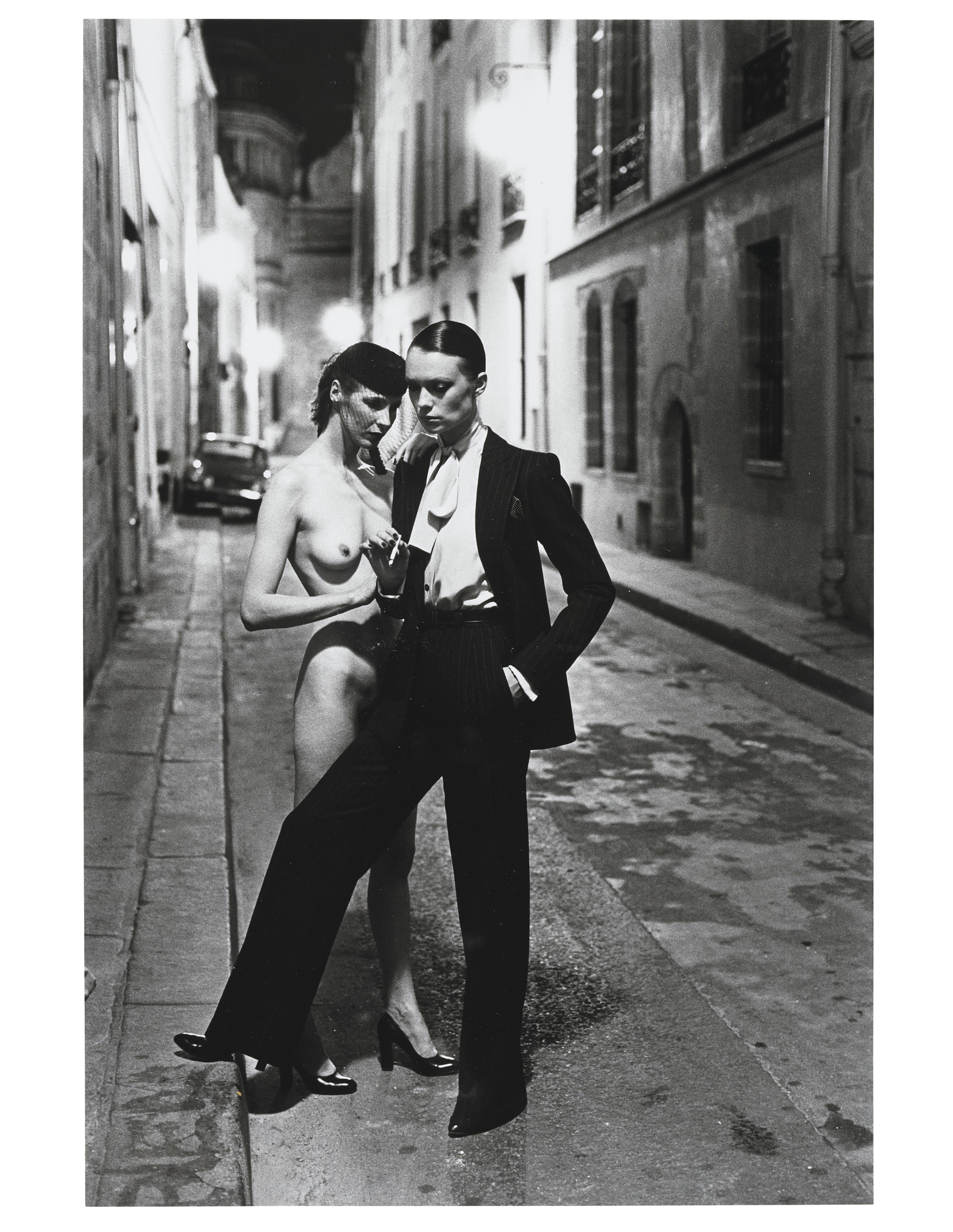

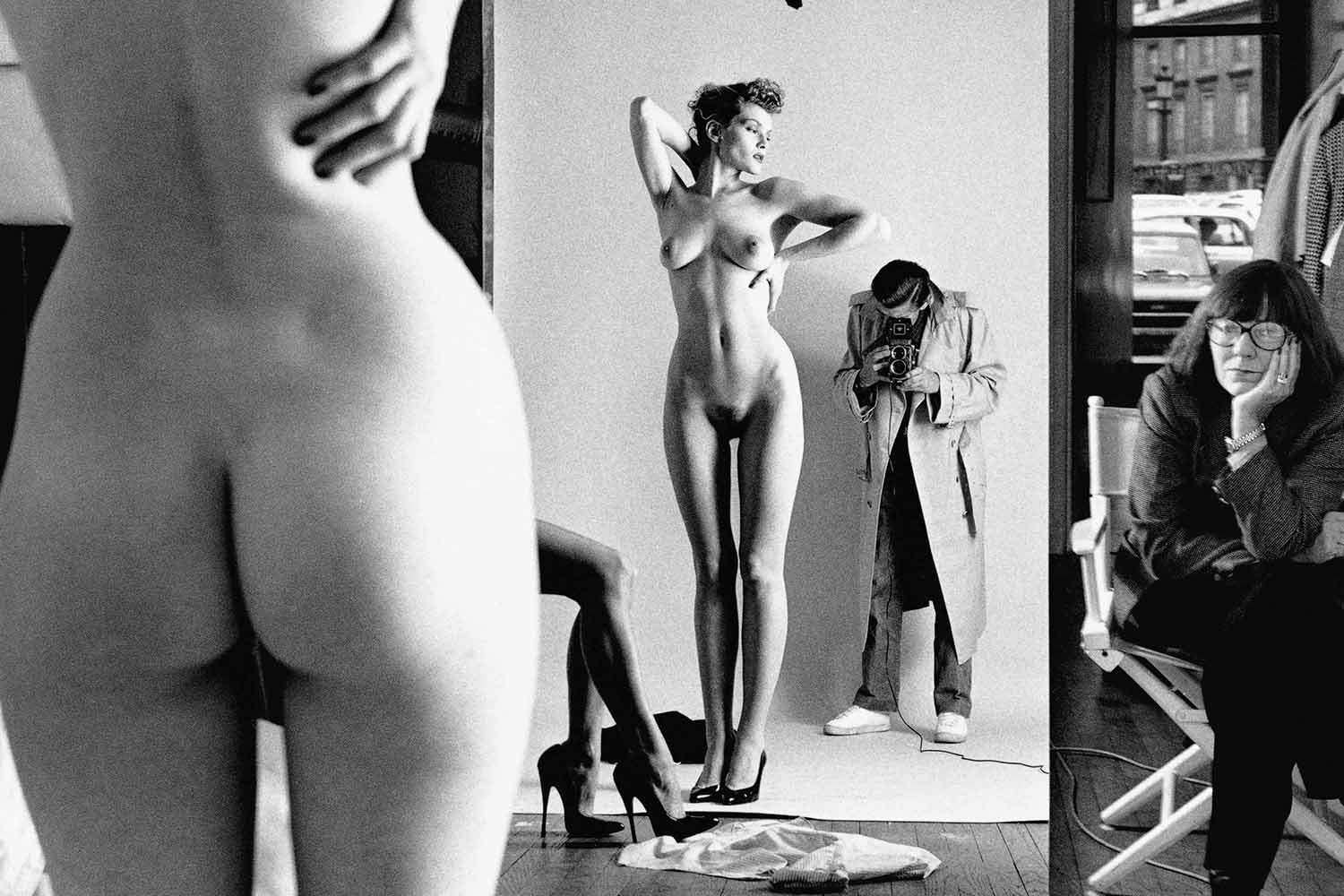

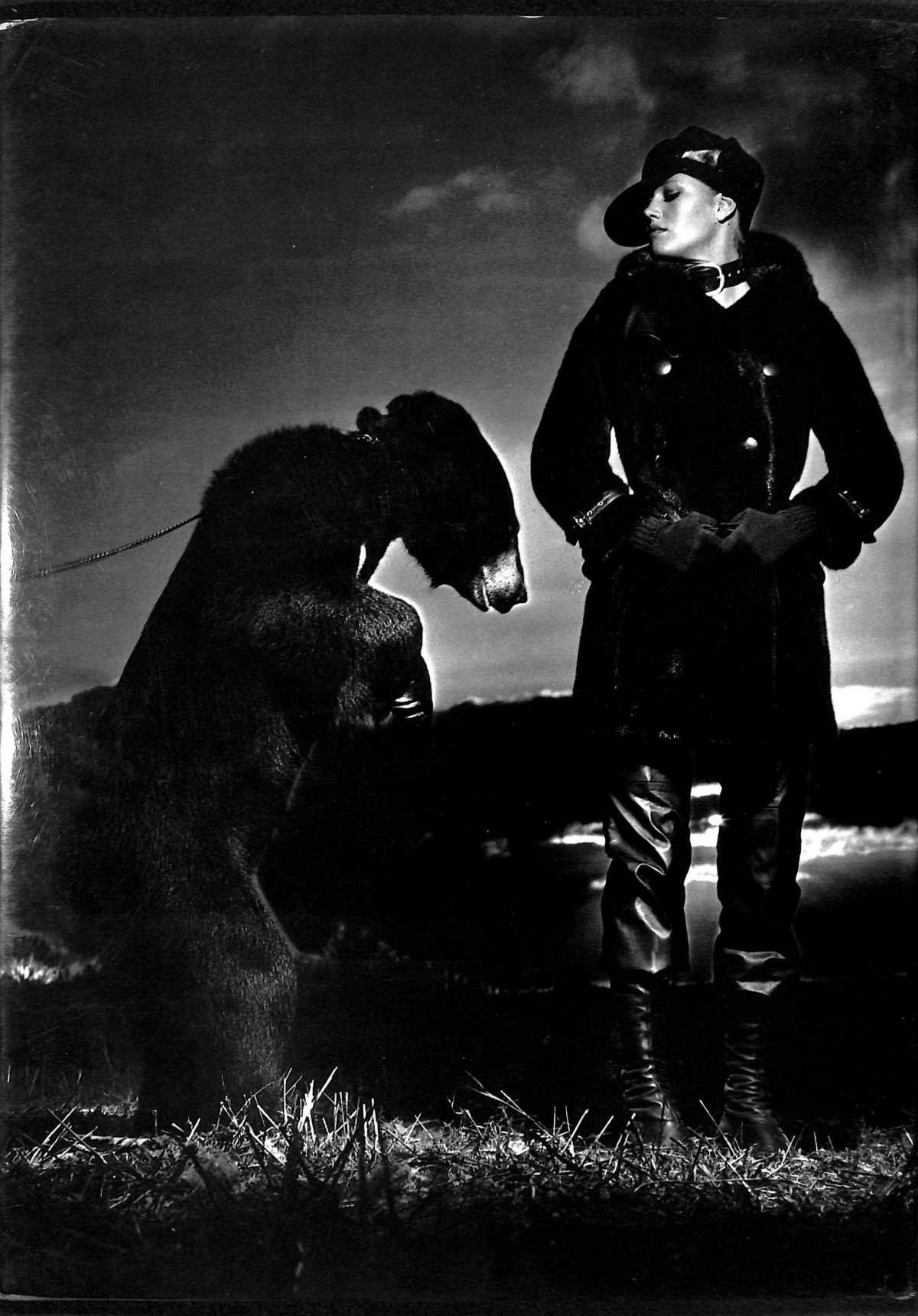

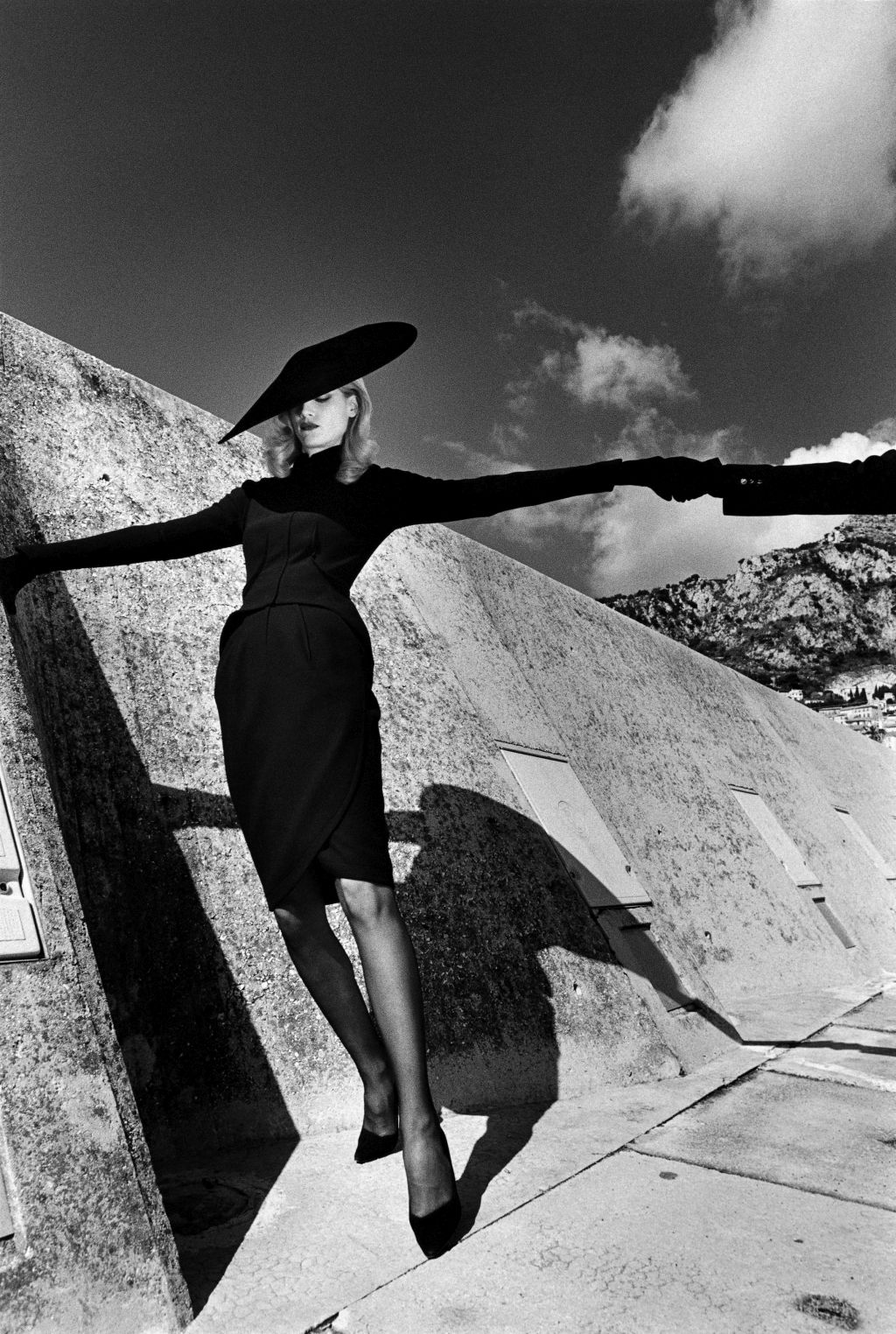

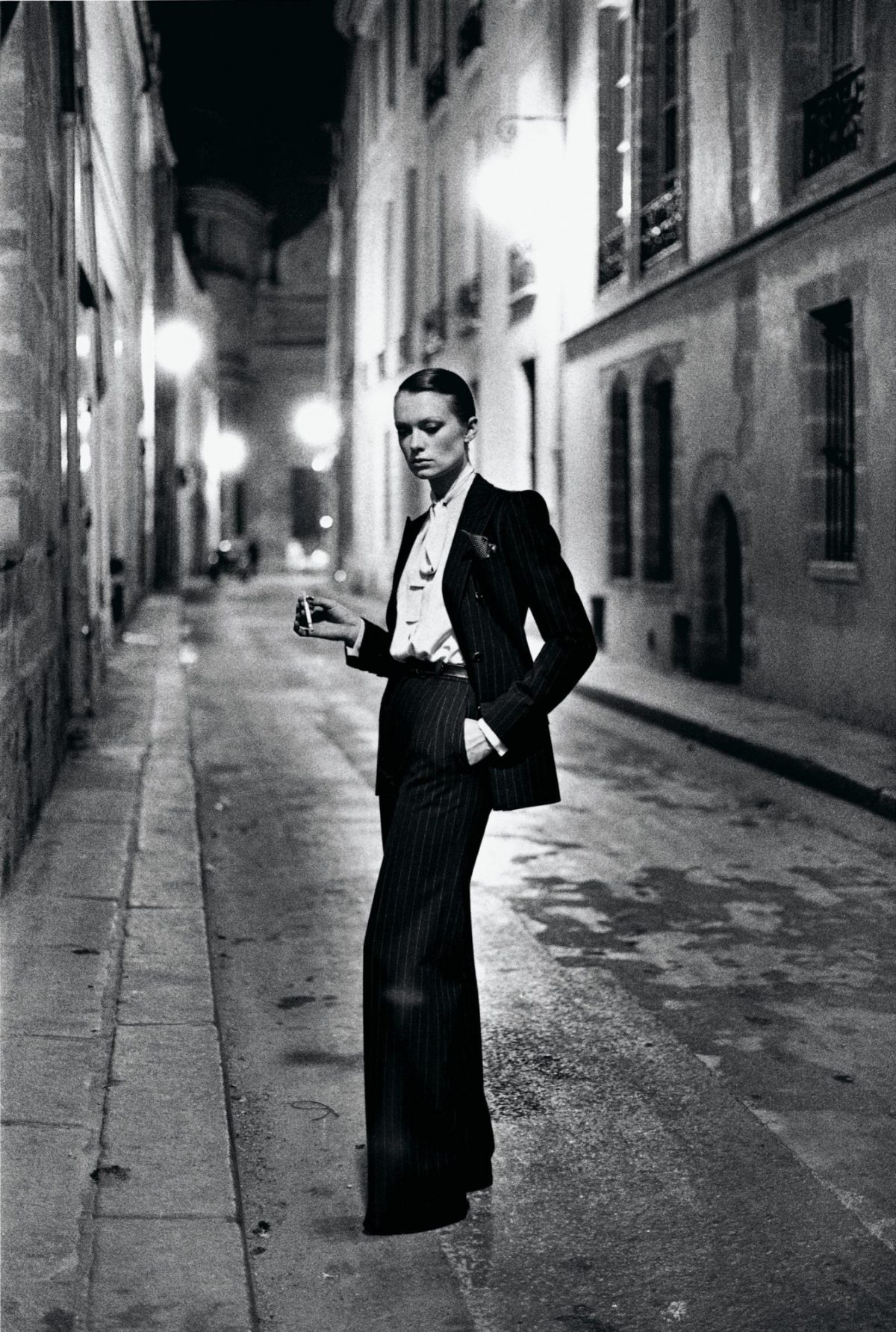

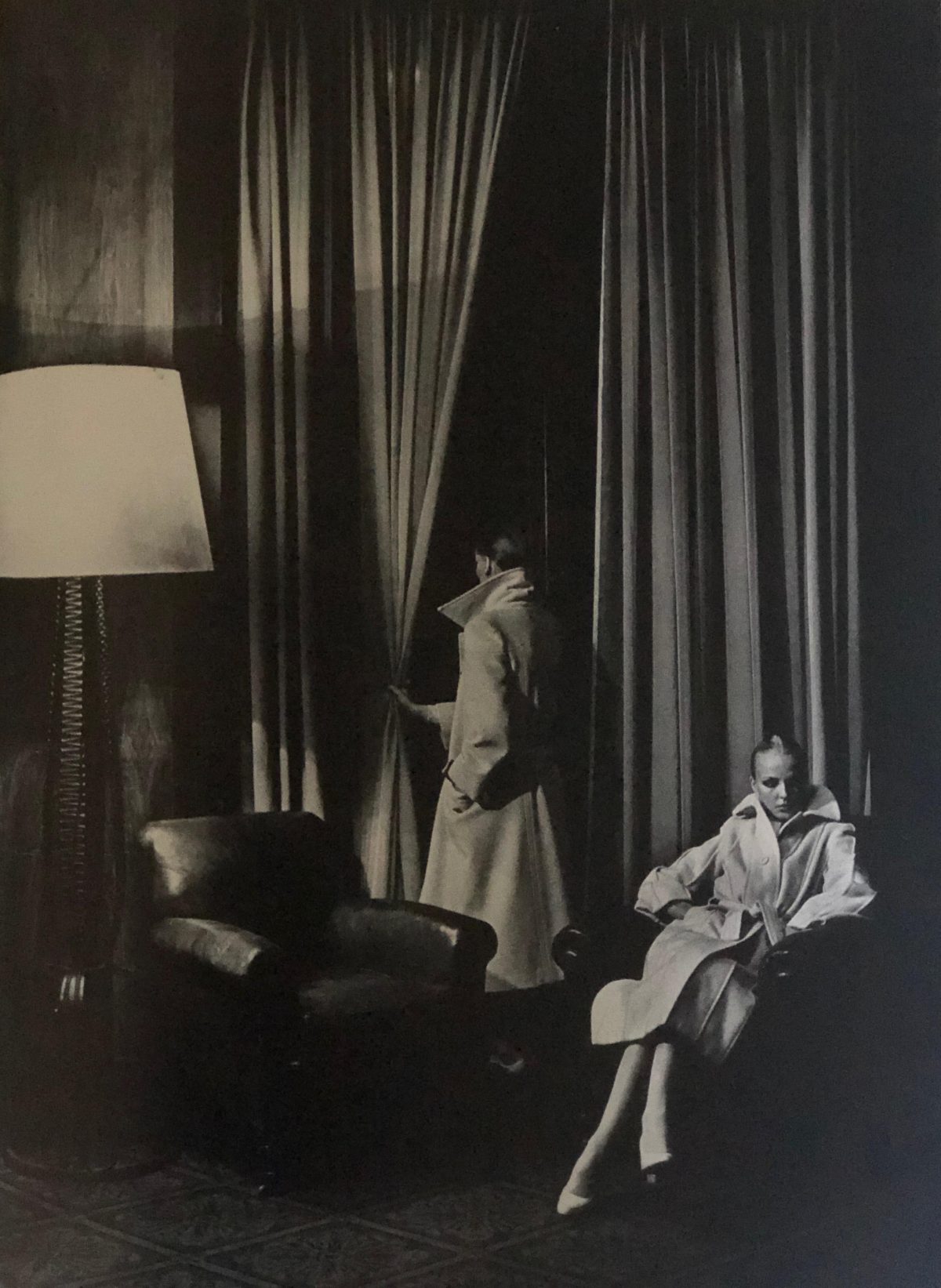

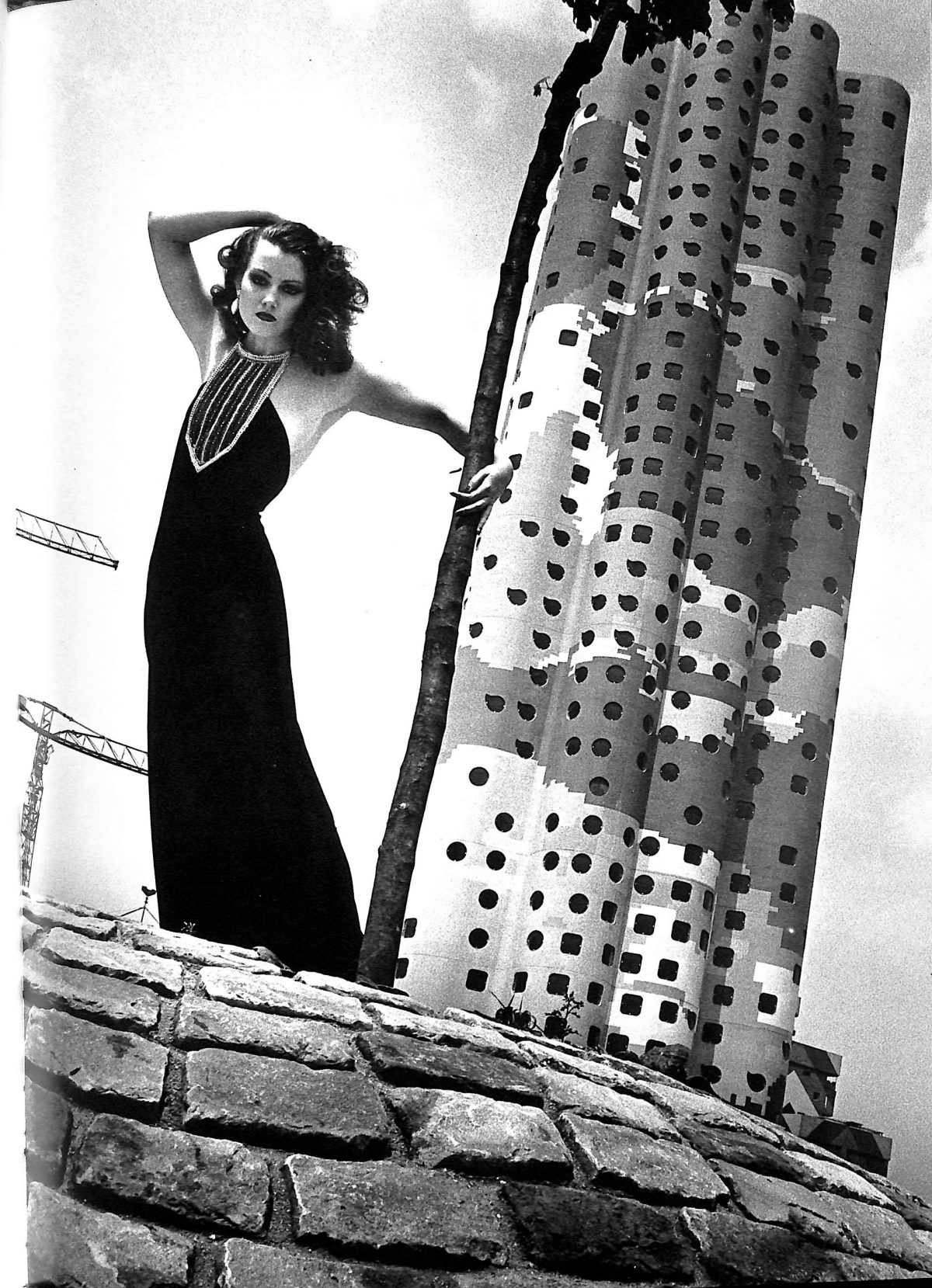

Newton’s cinematic spreads draw obvious influence from Weimar-era Expressionism and 40s Film Noir, with playful and unsettling twists. Although his own Jewish family escaped the Nazis in 1938, “Newton’s biggest influence, he says in the film, was Leni Riefenstahl, the German director hired to create highly stylized Nazi propaganda that idealized white, blonde, athletic German bodies” (His first book was called White Women.) “While Newton, and the rest of the world, came to understand the problematic roots of Riefenstahl’s compositions, he couldn’t deny their aesthetic prowess, and her eye cast a light over his work all his life.”

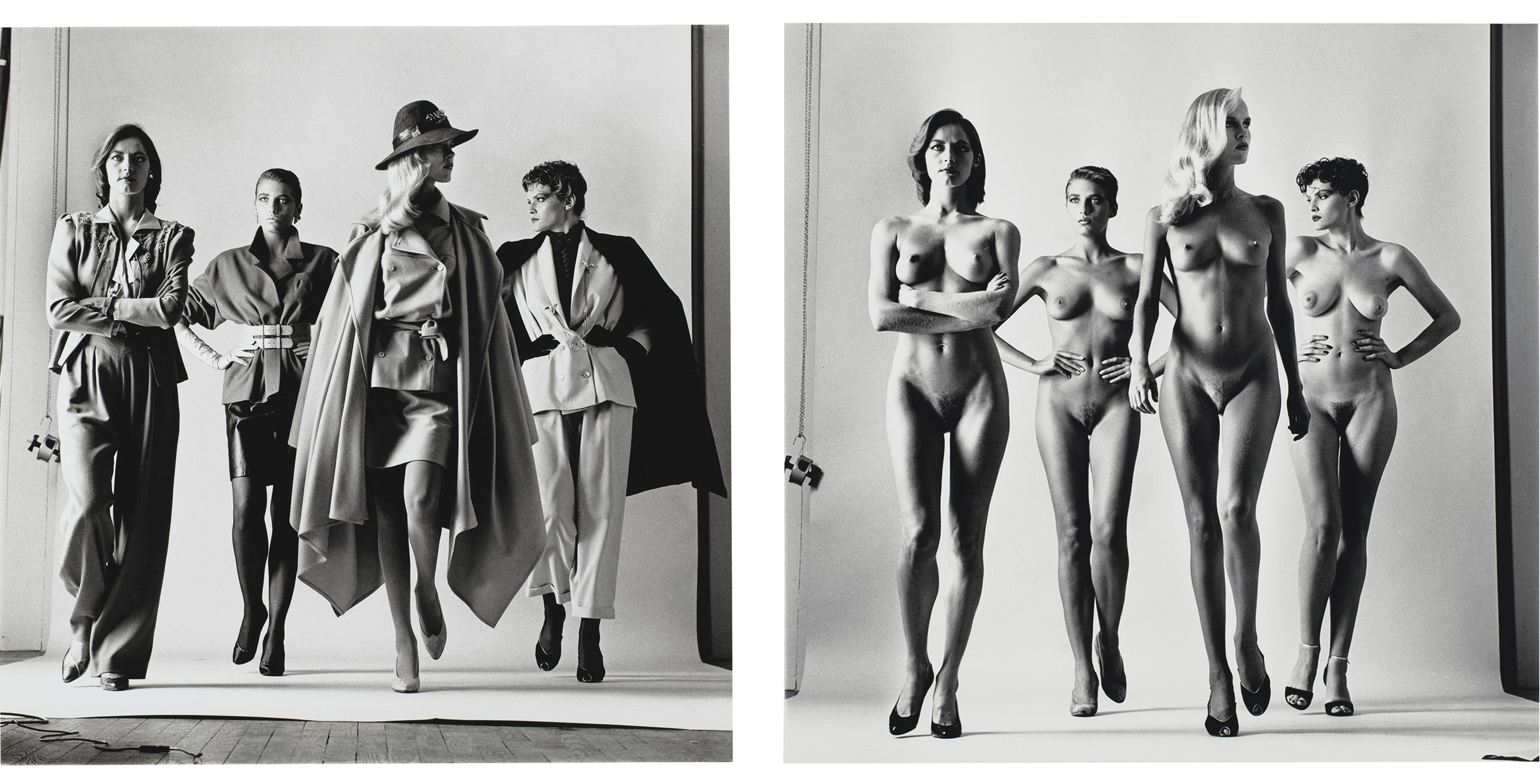

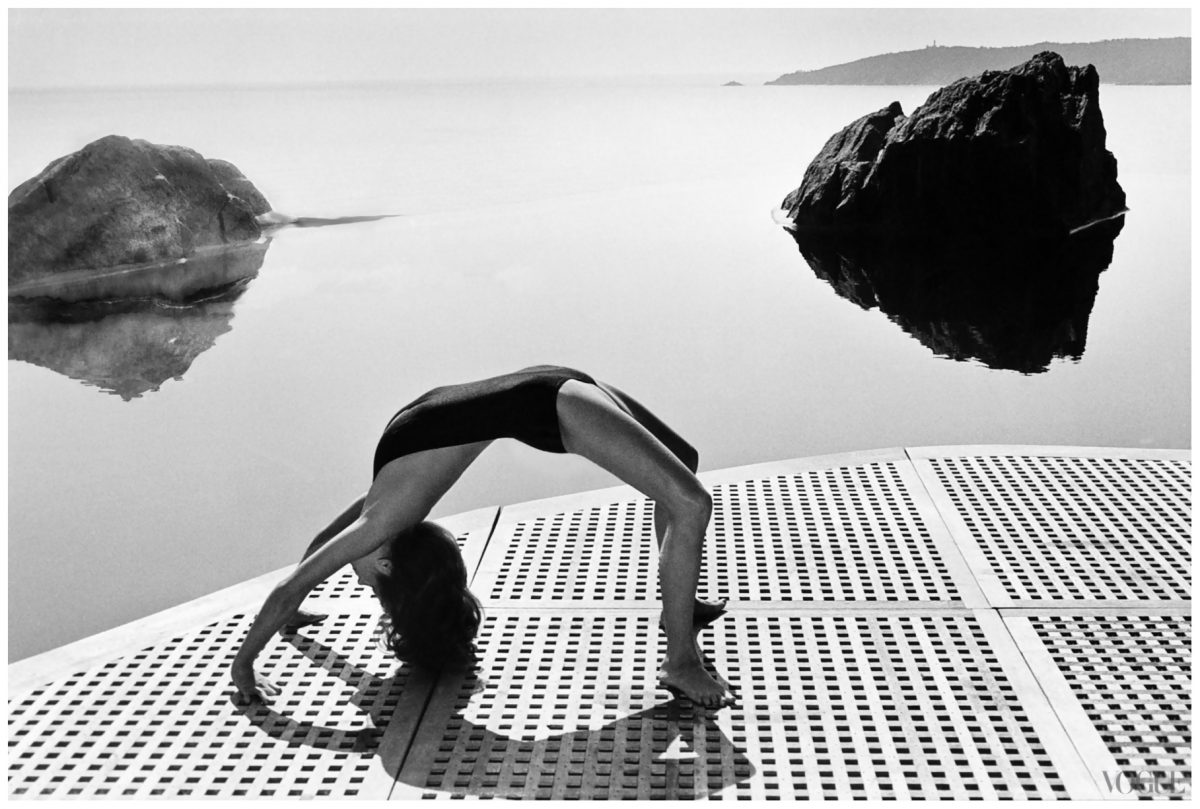

Despite his reputation as a sexist pervert, the women in Newton’s life – including Grace Jones, Isabella Rossellini, Charlotte Rampling, Claudio Schiffer, Anna Wintour, and his wife and partner, June, also a photographer – adored him. June encouraged Newton to pursue his aesthetic of “cool, statuesque, and sexually practiced women” in his most controversial work throughout the 70s and 80s. “His dramas stopped short of pornography,” Hamiltons Gallery writes, “and most took place in European jet-set retreats.”

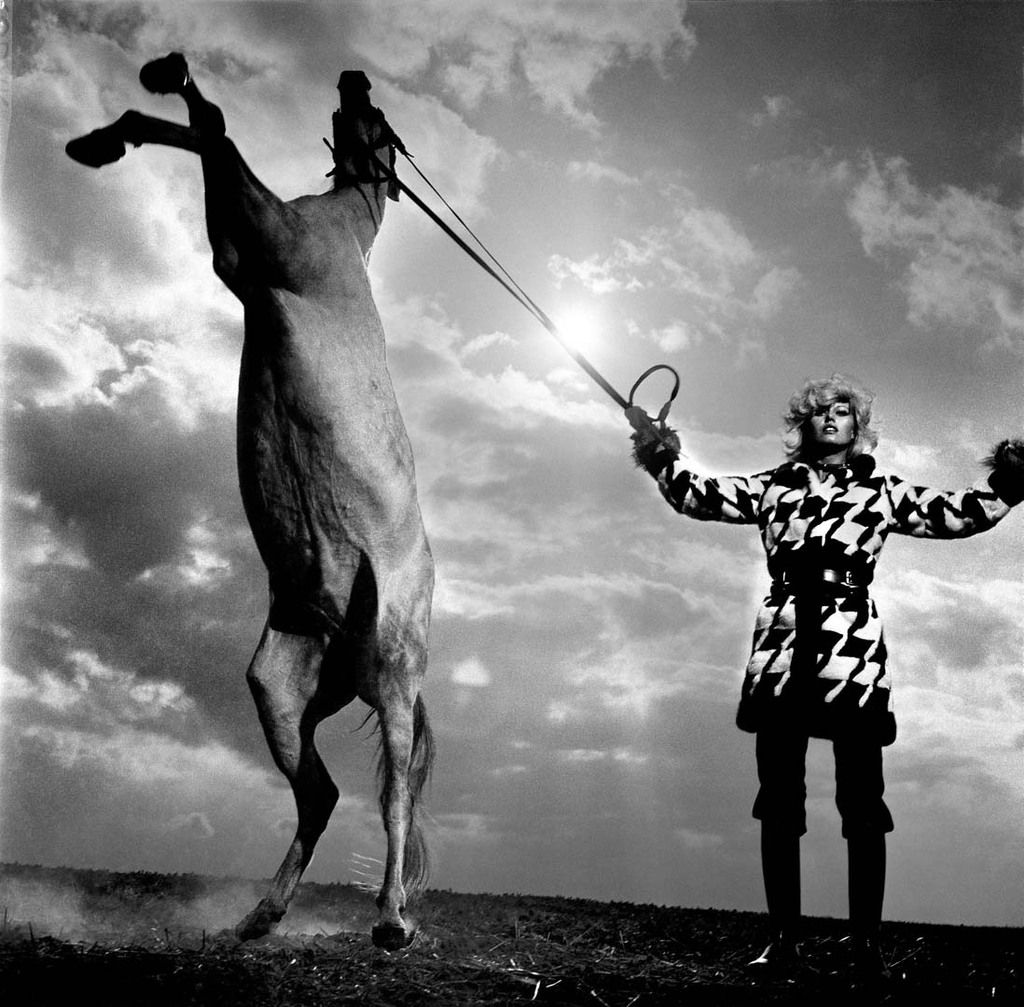

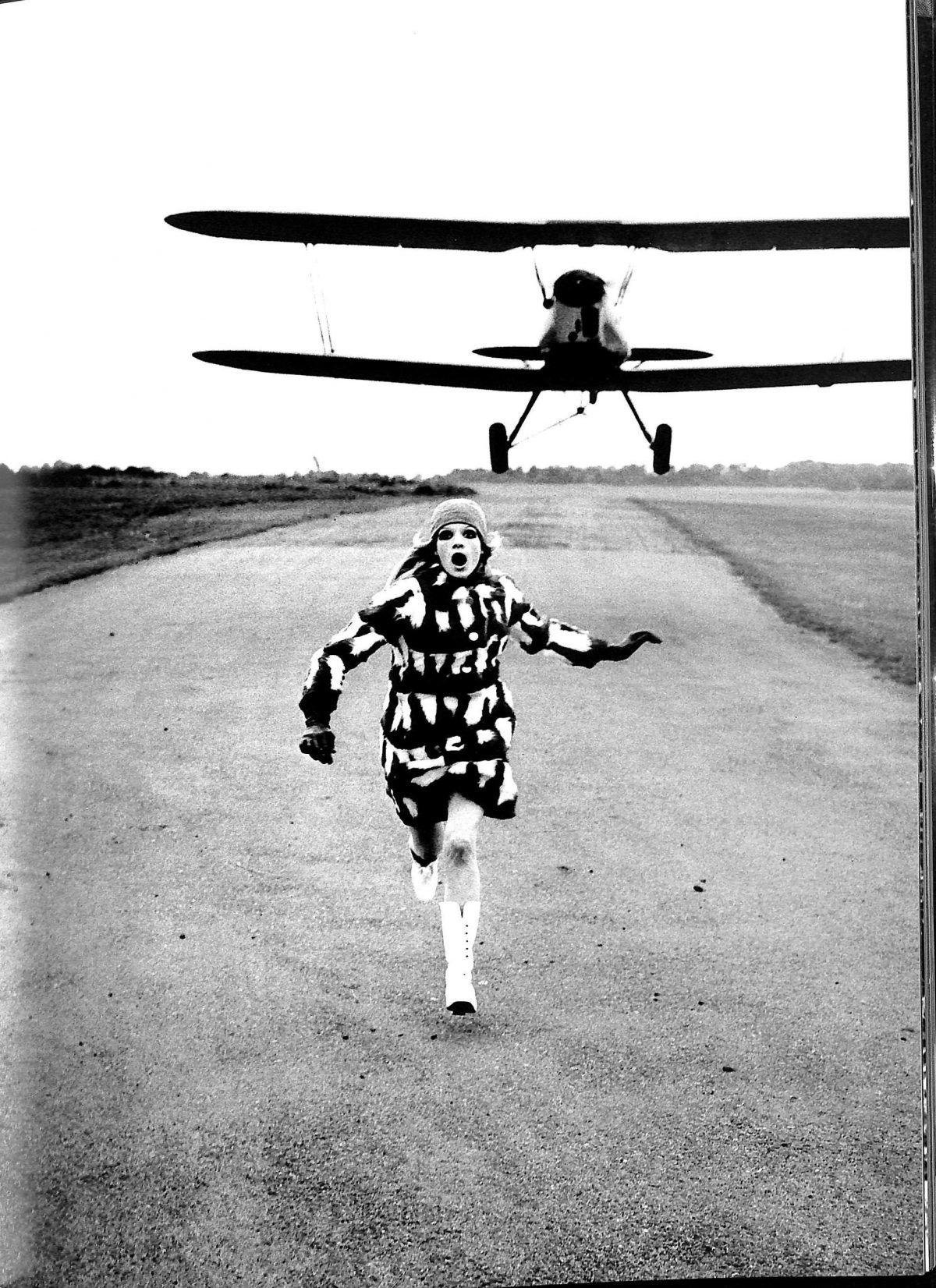

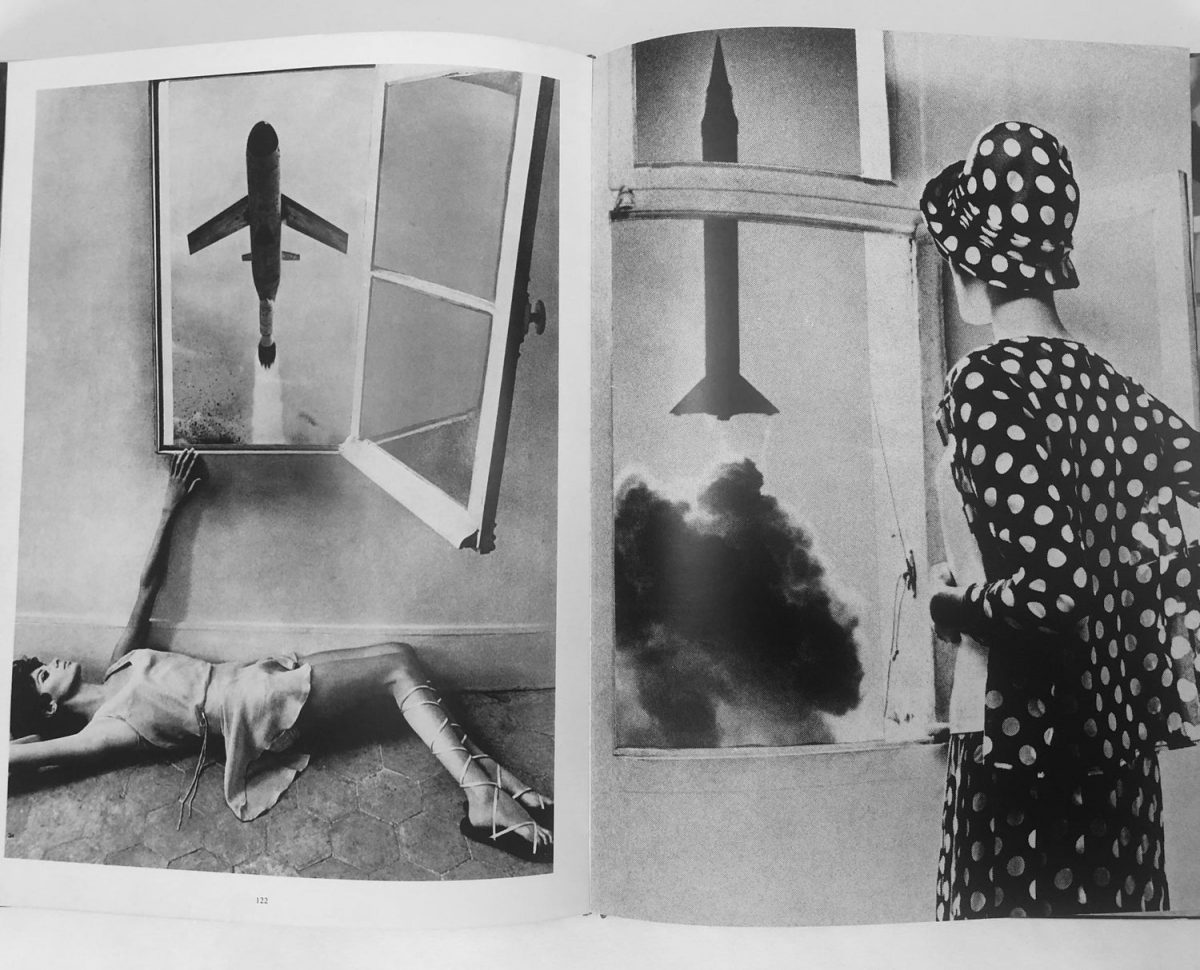

Newton also photographed in such out-of-the-way places as airfields and deserts. In 1984, he collected some of his boldest work from the late 60s to the early 80s in a book called World Without Men, which imagines his heroines “in peril pursued by planes in Hitchcockian fashion, or empowered,” Rob Wilkes writes, “holding down a rearing horse.” (We must wonder where the danger lies in a world without men.) The book, recently reissued by Taschen, also lent its title to a 2013 show in Berlin, arriving in a very different cultural moment than that of Newton’s best-known work.

“These photographs can certainly function as a criticism of the sexism that habitually plagues the media,” Becca Rothfeld argues at Hyperallergic. “They can reasonably read as satire and… as a celebration of female sexuality. But they can be read with equal validity as an endorsement of the flawed world that they depict…. Newton’s photographs… satisfy the most obvious and orthodox of male erotic expectations.”

Newton himself couldn’t have cared less about this critique. In his exchange with Sontag he appears “more chuffed than offended, immune to whatever cancel culture might’ve looked like in the 1970s,” Lattanzio observes. Maybe he would have felt differently if the culture had decided it no longer wanted to pay for his work. Newton may have pretended to imagine a world without men, but it was always a world seen through the very singular, obsessive gaze of a man named Helmut Newton.

“I still believe that the perfect fashion photograph is a photograph that does not look like a fashion photograph. It’s a photograph that looks like something out of a movie, like a portrait, maybe a souvenir shot, maybe a paparazzi shot, anything but a fashion photograph.”

– Helmut Newton

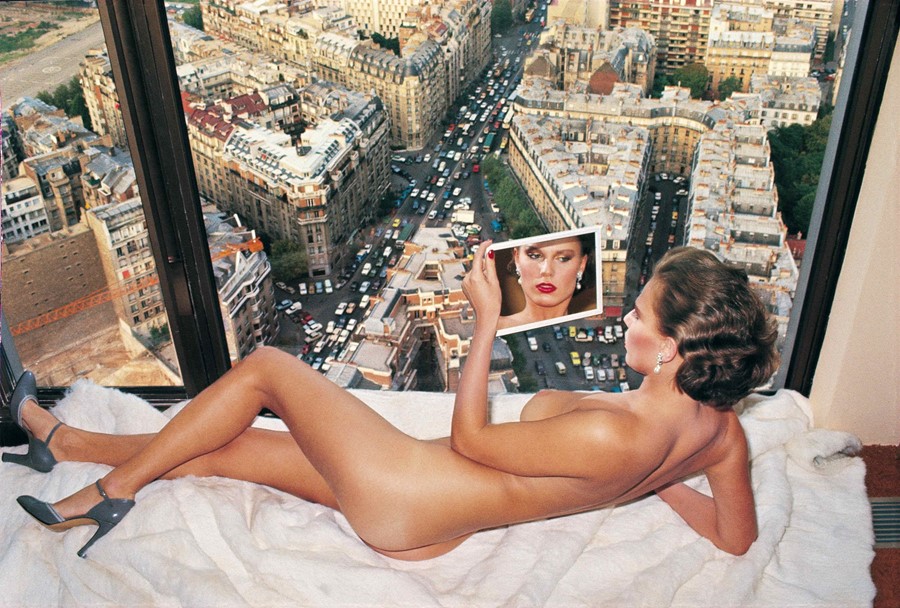

Bergstrom over Paris, 1976© Helmut Newton Estate

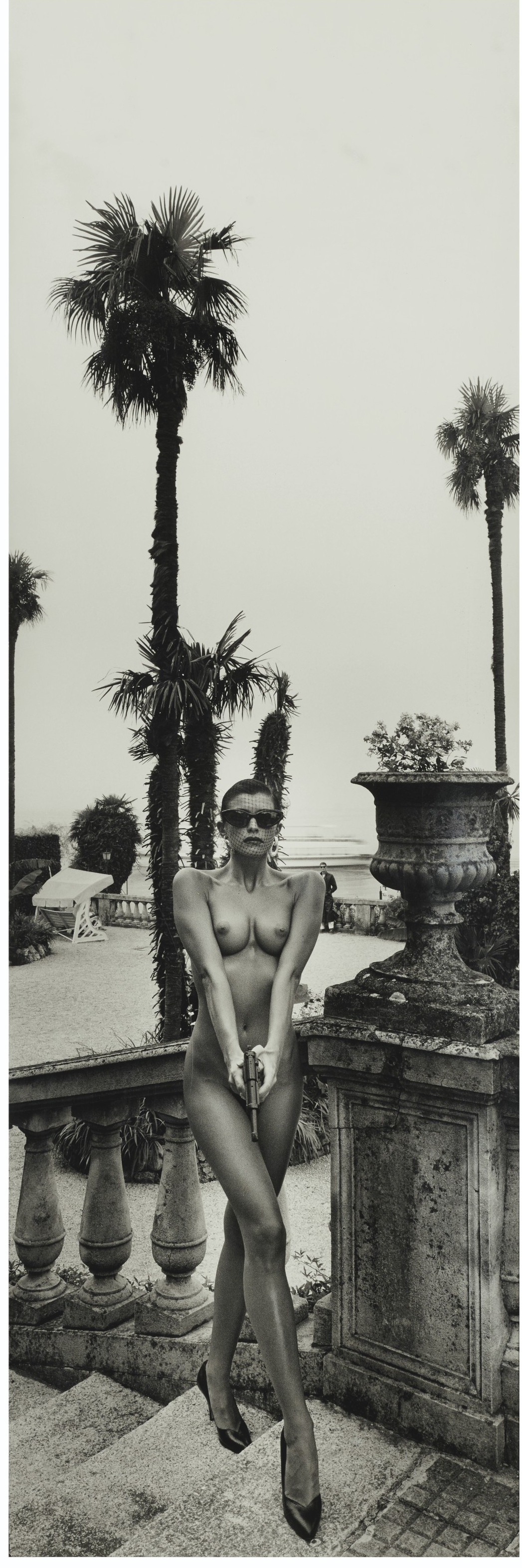

Helmut Newton (1920-2004), Panoramic Nude, Woman with Gun, Villa d’Este, Como, 1989. Gelatin silver print. Sheet: 61½ x 22 in (158.8 x 55.9 cm). Estimate: $300,000-500,000. Offered in Photographs on 2 October 2019 at Christie’s in New York

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.