Rosewater was twice as smart as Billy, but he and Billy were dealing with similar crises in similar ways. They had both found life meaningless, partly because of what they had seen in war. Rosewater, for instance, had shot a fourteen-year-old fireman, mistaking for a German soldier. So it goes. And Billy had seen the greatest massacre in European history, which was the fire-bombing of Dresden. So it goes.

— Kurt Vonnegut Jr., Slaughterhouse-Five

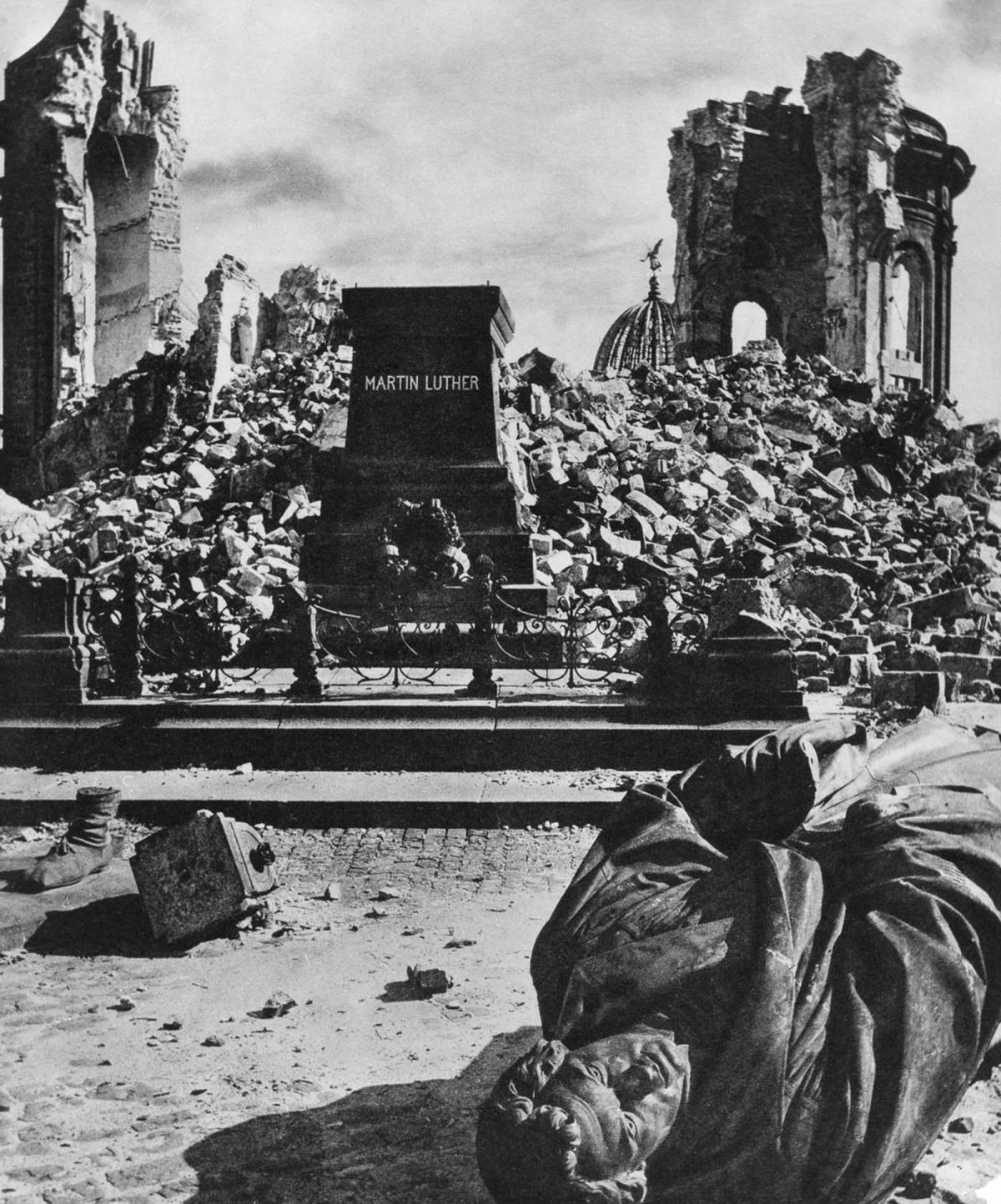

In terms of its ferocity, the firebombing of Dresden in February 1945 “was not unique” in Allied conduct of the war, Toby Luckhurst wrote on the 75th anniversary of the attack. Allied bombers had already “killed tens of thousands and destroyed large areas with attacks on Cologne, Hamburg and Berlin.” But the days-long destruction of Dresden with over 4,000 tons of explosives has remained a singular historical event, made famous by Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five and its sardonic depiction of the horrors on the ground.

Reports of the carnage caused even Winston Churchill, rarely given to qualms over civilian death, to question the “bombing of German cities simply for the sake of increasing the terror. The destruction of Dresden remains a serious query against the conduct of Allied bombing,” he wrote. Germany surrendered a few months later, rendering the question moot. Lately, the opinion that Dresden was a step too far has “taken on new meaning” in its use by “a resurgent far right,” Melissa Eddy writes in The New York Times. This unfortunate propaganda does not disqualify the view.

British survivor of the bombing and former P.O.W. Victor Gregg has written and spoken of his conviction that Dresden was a “war crime at the highest level, a stain upon the name Englishman.” He also admits, “I still suffer the memories of those terrible events and my anger refuses to subside.” He has been “regarded as some form of hero on the one hand to a Nazi supporter on the other.” Like Vonnegut, he wrote his memoir, Dresden: A Survivor’s Story, “to empty my mind and clear away the residue.”

As Vonnegut came to see it, the mass murder of civilians in a defenseless city known as the “Florence of the Elbe” and the mass murders committed by the Nazis were not linked in an inevitable causal chain. They were two species of incomprehensible moral crime, unstuck in time to return over and over in traumatic repetition, whether by means of aliens or PTSD, a condition the author wrote into the afflictions of his main character Billy Pilgrim and that he suffered from himself, though it had yet to be identified as such in 1969.

Vonnegut was “writing to save his own life,” his daughter Nanette has said. It was a book he had tried to write for twenty years as he relived the memories he first described in letters home to his family immediately after the events and later in interviews after the publication of the novel:

Every day we walked into the city and dug into basements and shelters to get the corpses out, as a sanitary measure. When we went into them, a typical shelter, an ordinary basement usually, looked like a streetcar full of people who’d simultaneously had heart failure. Just people sitting there in their chairs, all dead. A fire storm is an amazing thing. It doesn’t occur in nature. It’s fed by the tornadoes that occur in the midst of it and there isn’t a damned thing to breathe. We brought the dead out. They were loaded on wagons and taken to parks, large open areas in the city which weren’t filled with rubble. The Germans got funeral pyres going, burning the bodies to keep them from stinking and from spreading disease. 130,000 corpses were hidden underground. It was a terribly elaborate Easter egg hunt.

The official German death toll of the bombings was determined to be somewhere around 25,000, though “a widely accepted estimate is 35,000,” the National World War II Museum notes. “Since so many victims were immolated after the attacks” in fires that burned for weeks, “we will likely never know the precise number.”

Though he describes the fire storms themselves, what Vonnegut witnessed when he emerged from the underground abattoir known as Schlachthof 5, gone now but for a simple plaque, was aftermath. He did not see the “human torches” Gregg describes in his harrowing memoir. But the grisly work of what Vonnegut calls the “duty-dance with death” changed him irrevocably, as it changed everyone who lived through it.

At one point in his recollections, Vonnegut wonders what the German survivors must have thought as they watched him at “such gruesome work.” After speculating, he concludes, “who knows what they thought? Their minds may have been blank. I know mine was.” What can one think when faced with Dresden’s “skeletal, burned-out buildings,” Eddy writes, images that “have become synonymous with the ravages of war”? Allied P.O.W.s were left with shattered psyches and lives to try and piece together if they could. German survivors suffered the trauma of mass death and the total destruction of their historic city. They could and did rebuild, but they could also never forget.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.