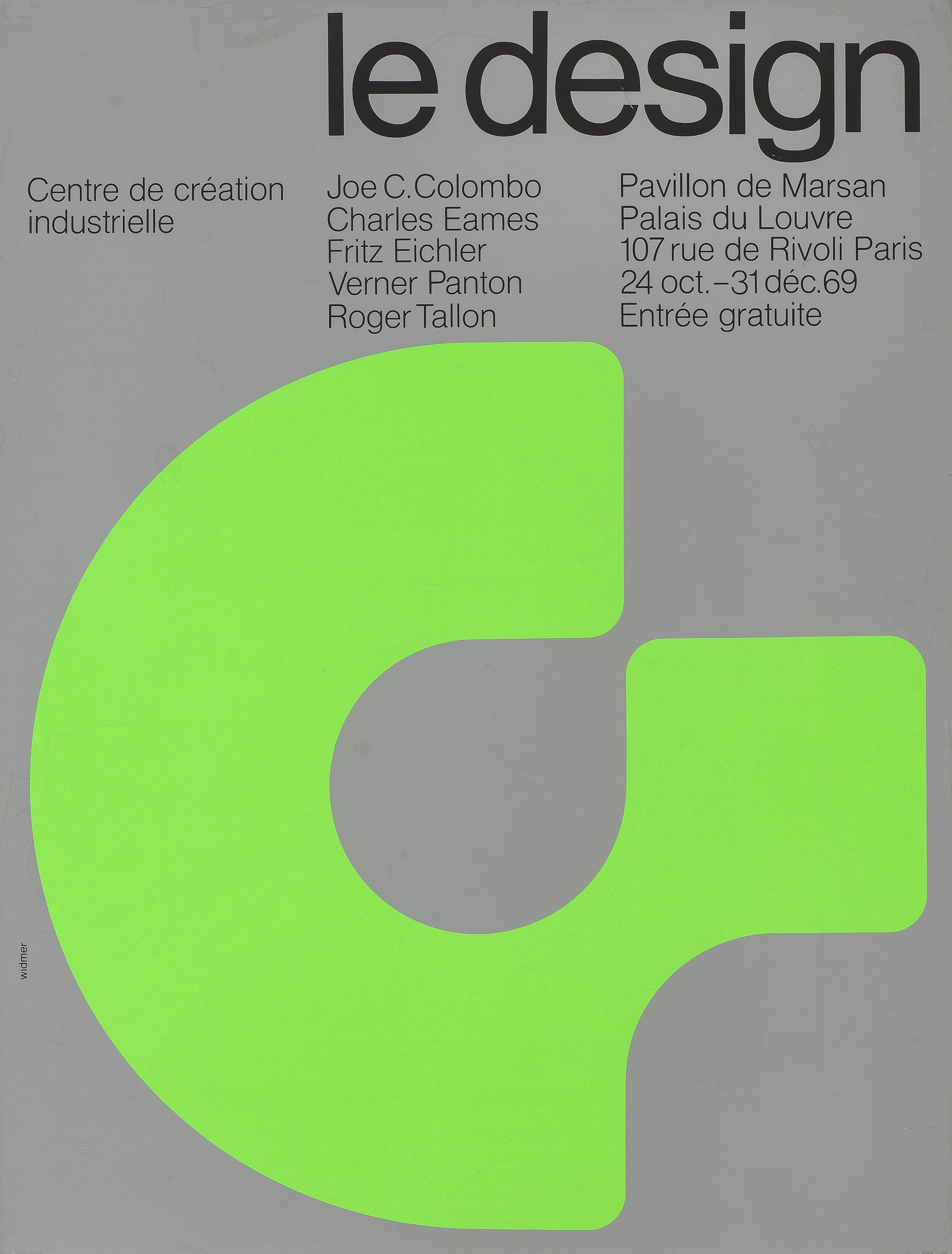

In 1969, Charles Eames was interviewed by Madame L’Amic of the Musée des Arts Decoratifs. She had curated the exhibition at the Louvre, Paris, What Is Design? (October 24, 1969 to January 15, 1970), at which Eames exhibited. Roger Tallon, Joe Colombo, Verner Panton, Fritz Eichler and Eames each answered a set of questions for the catalog on what design is. To Eames, it was all about “need”.

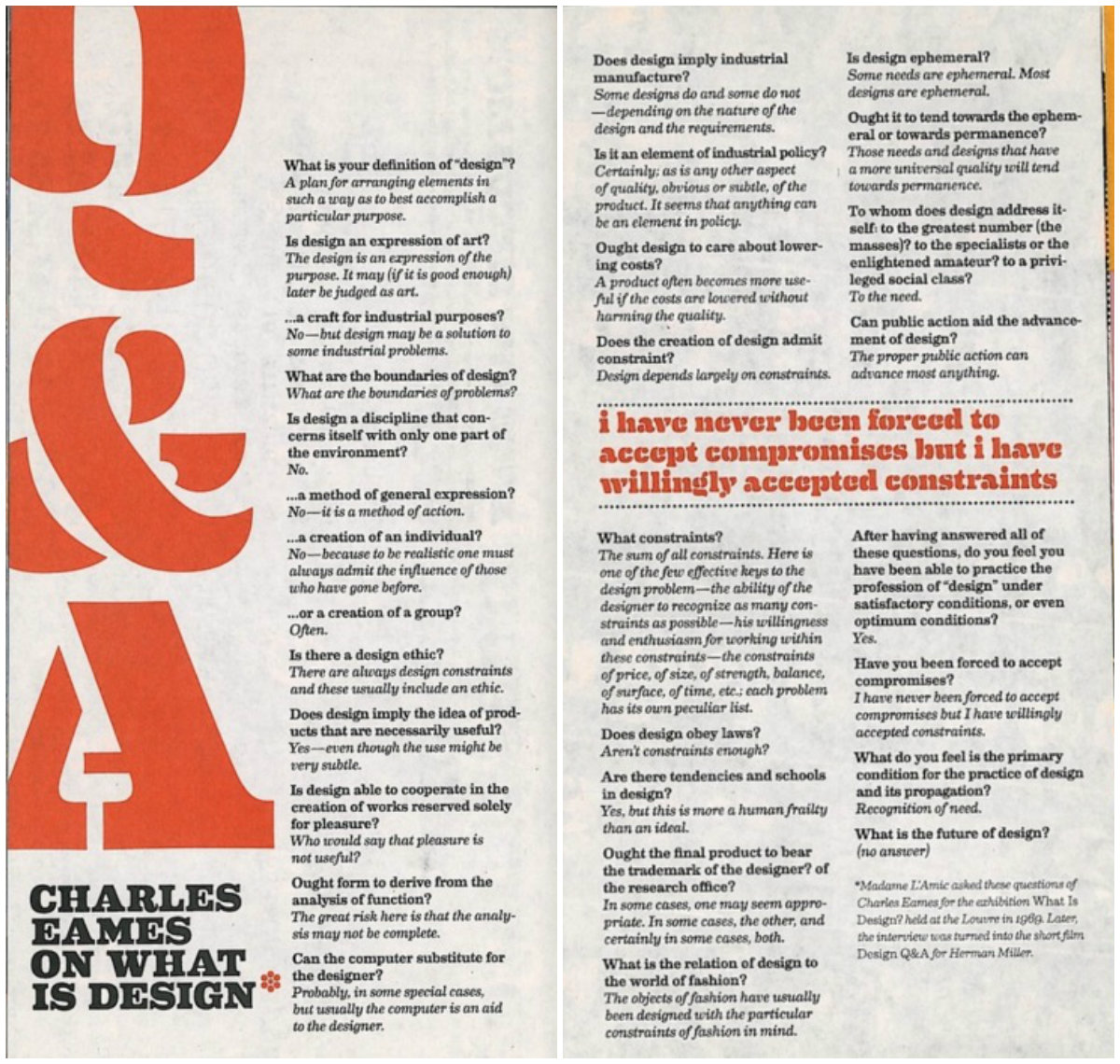

In 1972, the Q & A was turned into a short film, which you can see below. The transcript appeared in the House Industries’ typography journal (above).

Questions by Mme. L. Amic. Answers by Charles Eames.

Q: “What is your definition of ‘Design,’ Monsieur Eames?

A: “One could describe Design as a plan for arranging elements to accomplish a particular purpose.”

Q: “Is Design an expression of art?”

A: “I would rather say it’s an expression of purpose. It may, if it is good enough, later be judged as art.”

Q: “Is Design a craft for industrial purposes?”

A: “No, but Design may be a solution to some industrial problems.”

Q: “What are the boundaries of Design?”

A: “What are the boundaries of problems?”

Q: “Is Design a discipline that concerns itself with only one part of the environment?”

A: “No.”

Q: “Is it a method of general expression?”

A: “No. It is a method of action.”

Q: “Is Design a creation of an individual?”

A: “No, because to be realistic, one must always recognize the influence of those that have gone before.”

Q: “Is Design a creation of a group?”

A: “Very often.”

Q: “Is there a Design ethic?”

A: “There are always Design constraints, and these often imply an ethic.”

Q: “Does Design imply the idea of products that are necessarily useful?”

A: “Yes, even though the use might be very subtle.”

Q: “Is it able to cooperate in the creation of works reserved solely for pleasure?”

A: “Who would say that pleasure is not useful?”

Q: “Ought form to derive from the analysis of function?”

A: “The great risk here is that the analysis may be incomplete.”

Q: “Can the computer substitute for the Designer?”

A: “Probably, in some special cases, but usually the computer is an aid to the Designer.”

Q: “Does Design imply industrial manufacture?”

A: “Not necessarily.”

Q: “Is Design used to modify an old object through new techniques?”

A: “This is one kind of Design problem.”

Q: “Is Design used to fit up an existing model so that it is more attractive?”

A: “One doesn’t usually think of Design in this way.”

Q: “Is Design an element of industrial policy?”

A: “If Design constraints imply an ethic, and if industrial policy includes ethical principles, then yes—design is an element in an industrial policy.”

Q: “Does the creation of Design admit constraint?”

A: “Design depends largely on constraints.”

Q: “What constraints?”

A: “The sum of all constraints. Here is one of the few effective keys to the Design problem: the ability of the Designer to recognize as many of the constraints as possible; his willingness and enthusiasm for working within these constraints. Constraints of price, of size, of strength, of balance, of surface, of time, and so forth. Each problem has its own peculiar list.”

Q: “Does Design obey laws?”

A: “Aren’t constraints enough?”

Q: “Are there tendencies and schools in Design?”

A: “Yes, but these are more a measure of human limitations than of ideals.”

Q: “Is Design ephemeral?”

A: “Some needs are ephemeral. Most designs are ephemeral.”

Q: “Ought Design to tend towards the ephemeral or towards permanence?”

A: “Those needs and Designs that have a more universal quality tend toward relative permanence.”

Q: “How would you define yourself with respect to a decorator? an interior architect? a stylist?”

A: “I wouldn’t.”

Q: “To whom does Design address itself: to the greatest number? to the specialists or the enlightened amateur? to a privileged social class?”

A: “Design addresses itself to the need.”

Q: “After having answered all these questions, do you feel you have been able to practice the profession of ‘Design’ under satisfactory conditions, or even optimum conditions?”

A: “Yes.”

Q: “Have you been forced to accept compromises?”

A: “I don’t remember ever being forced to accept compromises, but I have willingly accepted constraints.”

Q: “What do you feel is the primary condition for the practice of Design and for its propagation?”

A: “A recognition of need.”

Q: “What is the future of Design?”

[unanswered]

Charles Eames’ conceptual diagram of the design process, displayed at the 1969 exhibition “What Is Design” at the Musée des Arts décoratifs in Paris.

Daniel Silvernail adds:

In Eames’ diagram [above] attending the exhibit we can see his mapping of the interests of the design office, the client, and those of the public. The diagram communicates that it is within the overlap where all three interests meet that the designer can work with conviction and enthusiasm (read passion).

His diagram also conveys that the design process is by its very nature an inherently “messy” business. Eames’ diagram is in it’s own unselfconscious way quite deliberately “wiggly”, mapping rational concepts to the wandering lines of an oft-times irrational process.

We architects do not generally like to show off the squiggly lines, fits-and-starts, design cul-de-sacs, whole design schemes tossed out towards the furtherance of the production schedule. Perhaps we should always do so, for same is at the very core of the process, despite (or perhaps better, because of ) the necessary reality of production budgets and deadlines. These are among the constraints Eames capably articulates in his diagram.

Every successful design, each successful work is infused with the design architect’s personal and unique approach to the design process, his recognition of the complexities and contradictions of the process, and his disciplined conviction and sincere passion in support of the realization of the design.

For the successful architect every design is an amalgam infused, by design, with the mystique of alchemy.

The film below is voiced by Eames and Madame L’Amic:

Via: Social Action, Eames, Les Arts Decoratifs

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.