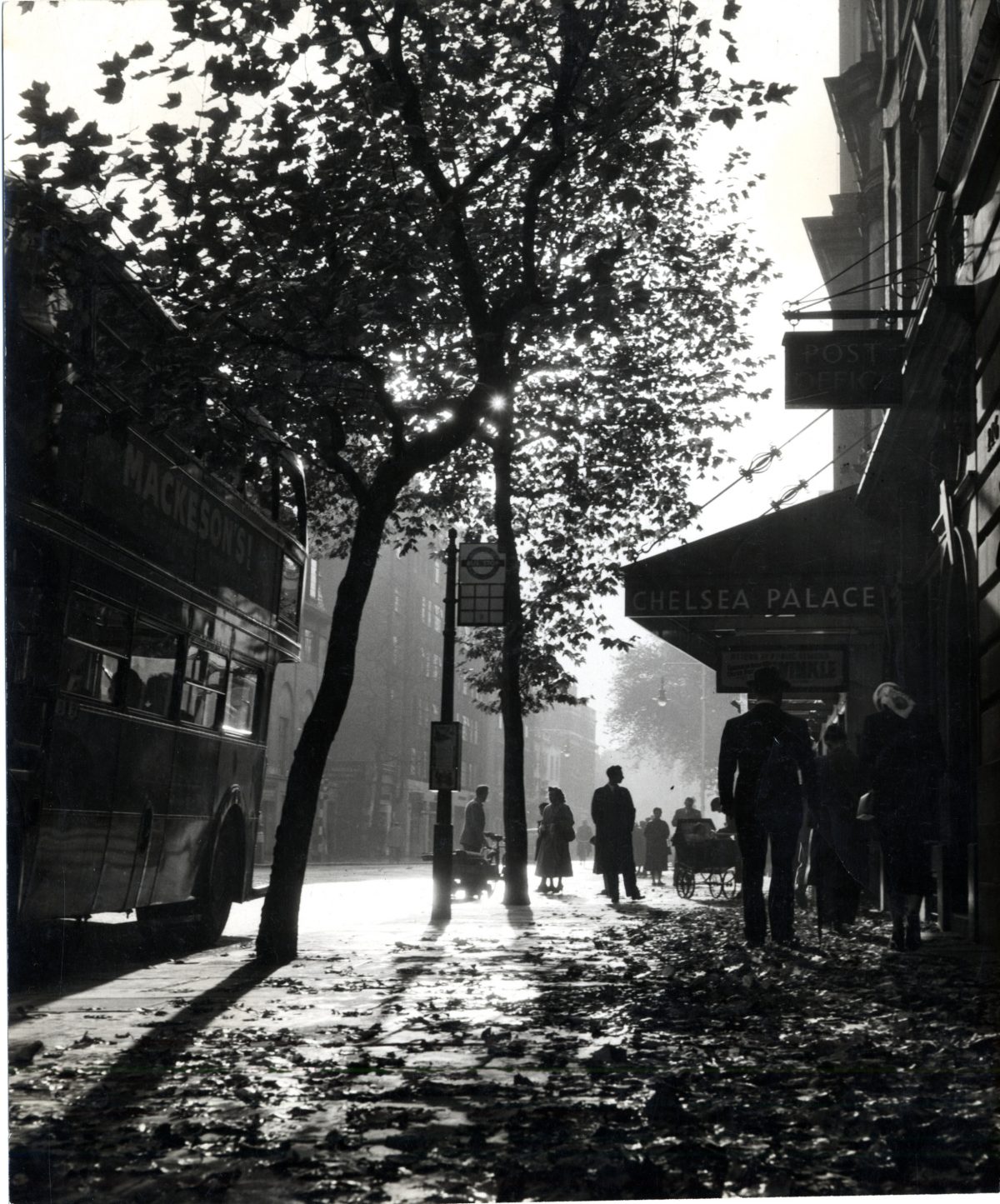

On 23 February 1959 a gaunt and very unsteady Billie Holiday was helped up on stage and performed three songs for a television show called Chelsea at Nine. The show was produced in Granada’s Studio 10 situated in the former Chelsea Palace theatre at 232-242 King’s Road. Luckily for us the show was ‘Ampex-ed’ by Granada and the recording still survives. Holiday was patently unwell but the extraordinary performances of ‘Strange Fruit’, ‘Please Don’t Talk About Me When I’m Gone’ and ‘I Loves You Porgy’ are among the last she ever made. She died just five months later of cirrhosis of the liver while, courtesy of the New York police, handcuffed to a hospital bed in New York.

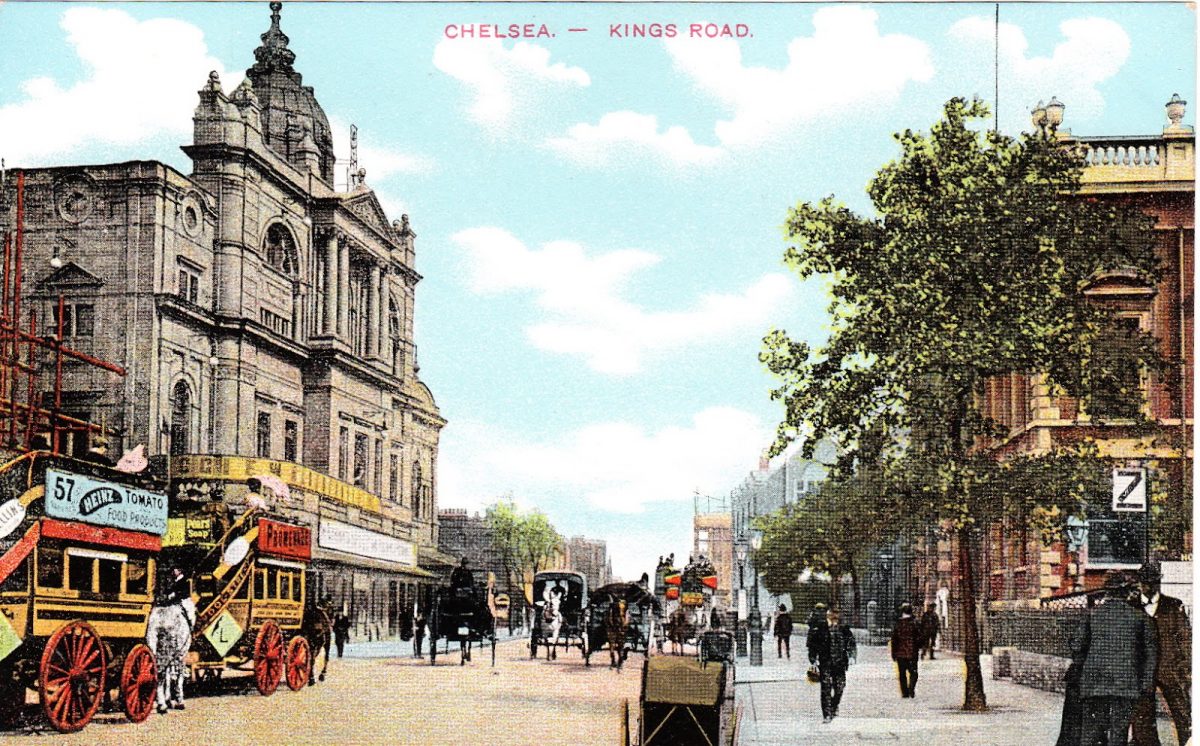

The terracotta-clad Chelsea Palace of Varieties, as it was originally known, was situated on the corner of Sydney Street,and was originally a music hall designed by the noted theatre designers Oswald Wilson and Charles Long in 1903. By 1923 it started to be used as a cinema as well as showing straight plays and ballets but within two years, in 1925, it was taken over by Variety Theatres Consolidated, and from then on it presented mostly live theatre.

By 1956, however, the Chelsea Palace was struggling and at the end of November, after fifty-three years, its life as a music hall came to an end. Not long before it closed, and while his wife Mary Ure was in rehearsals for Arthur Miller’s A View From the Bridge, which would open at the Comedy Theatre in October, John Osborne decided to go to the Palace and see Max Wall, who was headlining a variety bill. He was just in time to catch an act lower on the bill performing an impression of Charles Laughton in his famous role as Quasimodo. Osborne later wrote about the experience: ‘A smokey green light swirled over the stage and awesome banality prevailed for some theatrical seconds, the drama and poetry, the belt and braces of music hall holding up an epic.’ Osborne saw a sort of odd heroic nobility in the awful talentless performer who came on stage night after night to almost certain derision.

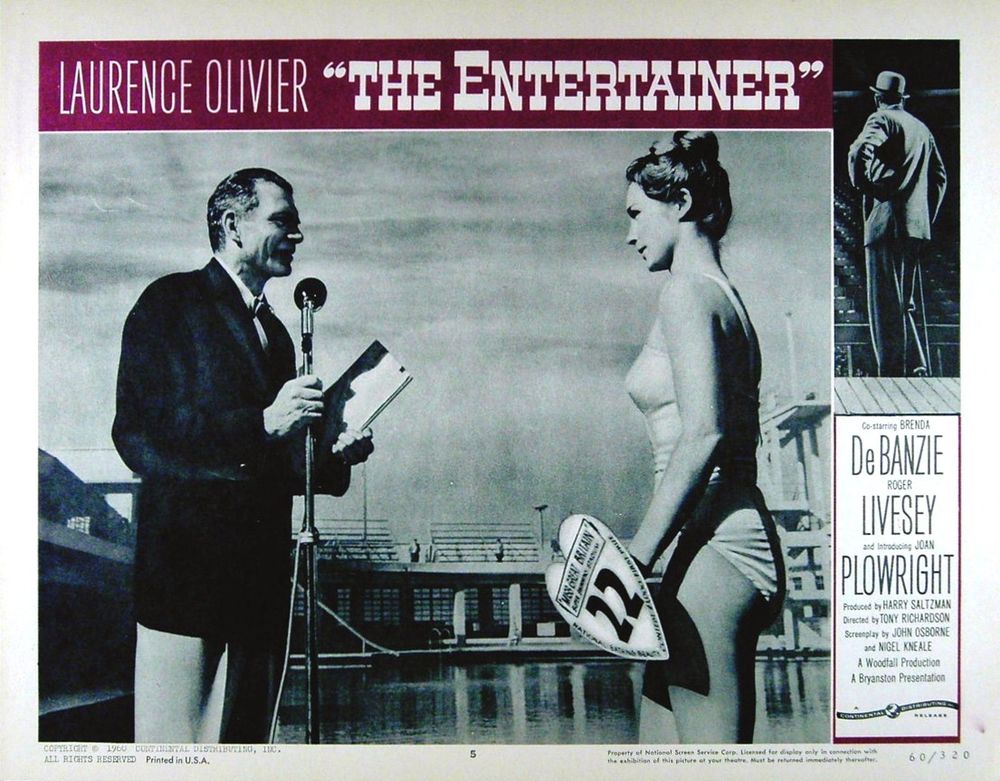

The visit to the Chelsea Palace that evening inspired The Entertainer, his play about Archie Rice, the failing music hall artiste. When Laurence Oliver had been chosen for the role, Osborne decided to take him on a tour of the music halls in London, or what was left of them. Osborne hadn’t realised that when he was writing his play about the dying music hall, places like the Met in Edgware Road and Collins’ in Islington were actually all about to be closed. Osborne took Olivier to Collins’ where he had wanted him to see a Scottish comedian called Jack Radcliffe who performed a death-bed scene. Taking Britain’s greatest classical actor to watch a sketch about death by a ‘dying’ comic in front of a gloomy, melancholic audience would, he thought, be excellent research for Olivier, who, to put it in Osborne’s words, ‘could hardly have witnessed such a farewell to hope and dignity’.

The Entertainer opened the following year at the Royal Court Theatre. Osborne always thought that Laurence Olivier had overshadowed the original production and seventeen years later decided to produce the play himself; this time he cast Max Wall, who he had gone to see all those years ago at the Chelsea Palace. At that time, in 1974, Max Wall was bankrupt and living in a bedsit. His wife, twenty-six years his junior, had just left him, leaving a note that said, ‘You will end up in one room, alone, with nothing.’ Wall’s performance opened to mixed reviews and in Tatler, Sheridan Morley wrote that the production was ‘a massive disappointment, rather like seeing King Lear played by a real old king. Mr Wall contrived to be … too great a comedian, so one could never understand what he was doing in a tatty nudie show’. The Daily Mail’s Roderick Gilchrist completely disagreed and considered that this made the casting all the more apt: ‘Max Wall, with those sad, bloodhound eyes and face like a well-hammered coconut, is not merely acting – but living again experiences from his own life.’

In 1957, while the original production of The Entertainer was still on at the Royal Court, the Chelsea Palace was renamed the Chelsea Granada and was to become a cinema. However, almost immediately, the building was leased to Granada Television, within the same company, and the stalls in the theatre were replaced by a studio floor. To augment Granada’s specially built studio complex in Manchester, it became Studio 10 for the next eight years. Sidney Bernstein, who with his brother Cecil owned Granada, which had recently won the franchise license to broadcast commercial television in the north west of England, numbered their studios with just even numbers, simply so it appeared that they owned more studios than they did. The Chelsea Palace, or Studio 10 as it was now called, was actually the last of the London theatres to be converted into a TV studio. The Shepherd’s Bush Empire was already a BBC studio, while Associated Television had already converted the Hackney Empire and the Wood Green Empire. Incidentally, it was at the Wood Green Empire, in 1918, that the Chinese magician known as Chung Ling Soo was tragically shot and fatally injured while performing his infamous act that involved catching a bullet between his teeth. His last words were: ‘Oh my God. Something’s happened. Lower the curtain.’ It shocked everyone. Not so much that he had been shot, but that he wasn’t Chinese and spoke perfect English.

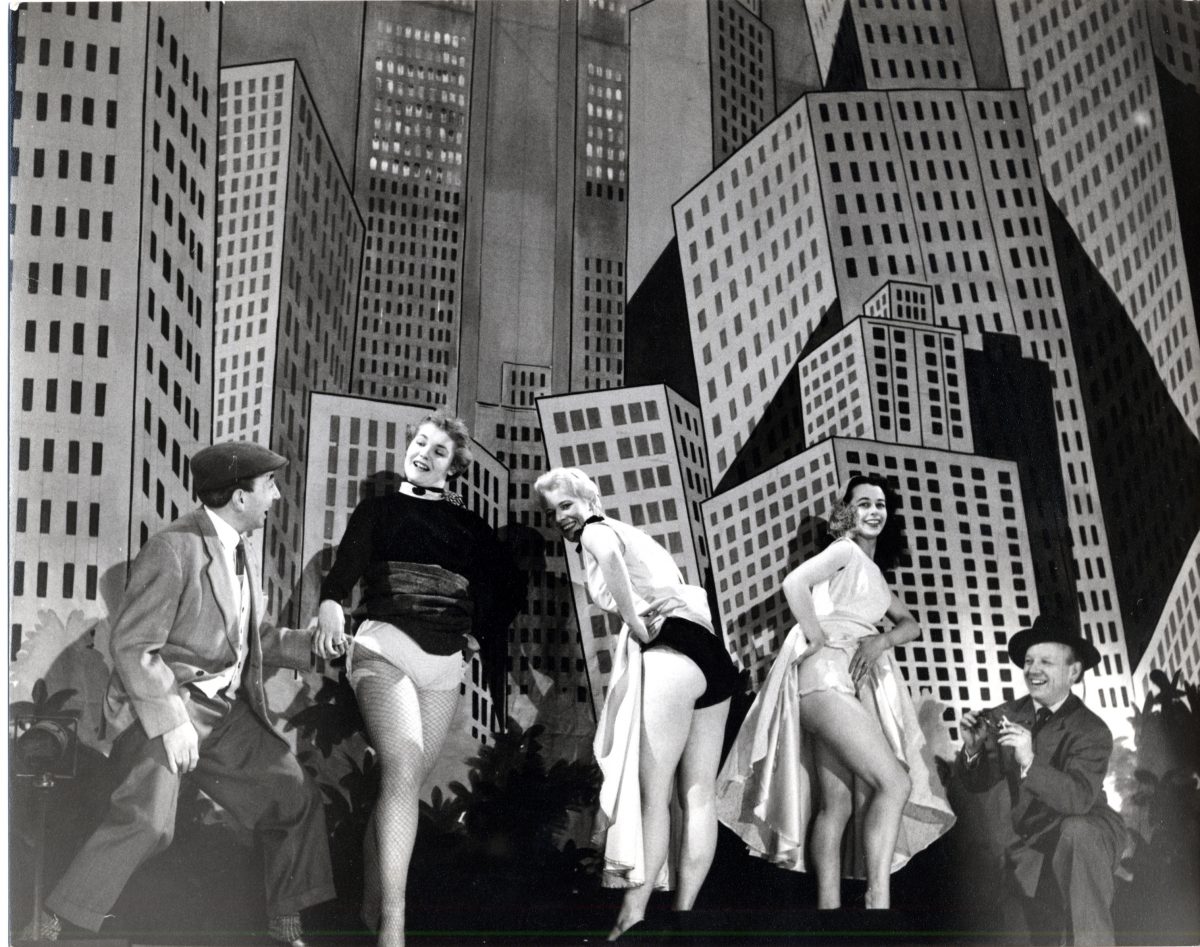

Studio 10 was used for the long-running and extremely popular comedy series The Army Game, which ran for five years from 1957. An incredible 154 episodes were broadcast, and the cast included many that would become household names for decades to come. Alfie Bass, Geoffrey Palmer, Bill Fraser, Dick Emery and Bernard Bresslaw were all regulars, while the writers included a young John Junkin, Marty Feldman and Barry Took. Another very popular show that came from Granada’s King’s Road studio was the variety show called Chelsea at Nine. It ran for three series and purposely took advantage of the studio’s location in the capital to feature artists that were appearing in the West End. This meant that occasionally you would get one of the nest jazz musicians on earth coming straight on after a comedian who would struggle to get on the end of a bill in Skegness. Ella Fitzgerald once had to introduce an act, which was appearing after her on the show, as ‘the world’s greatest song-and-dance spoons man’. Every time she tried the link she started to laugh and simply couldn’t do it.

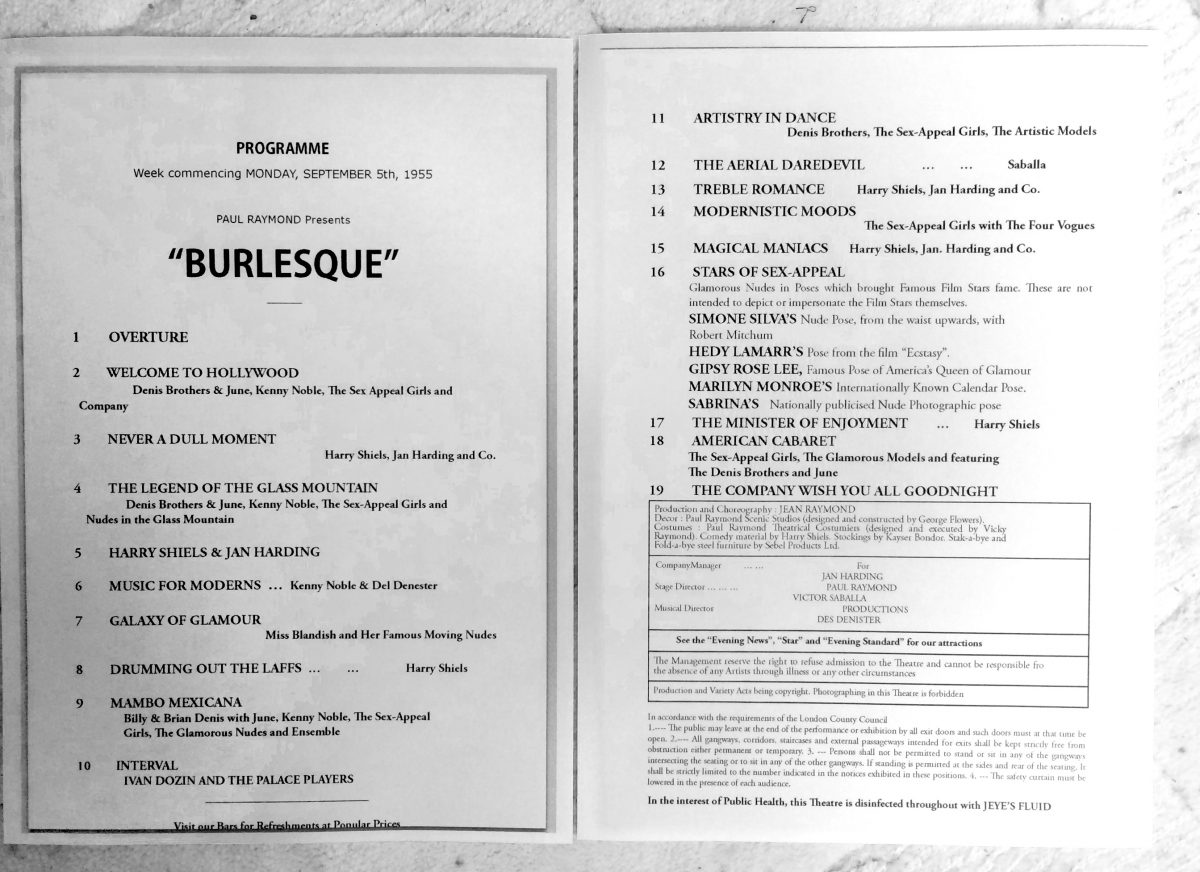

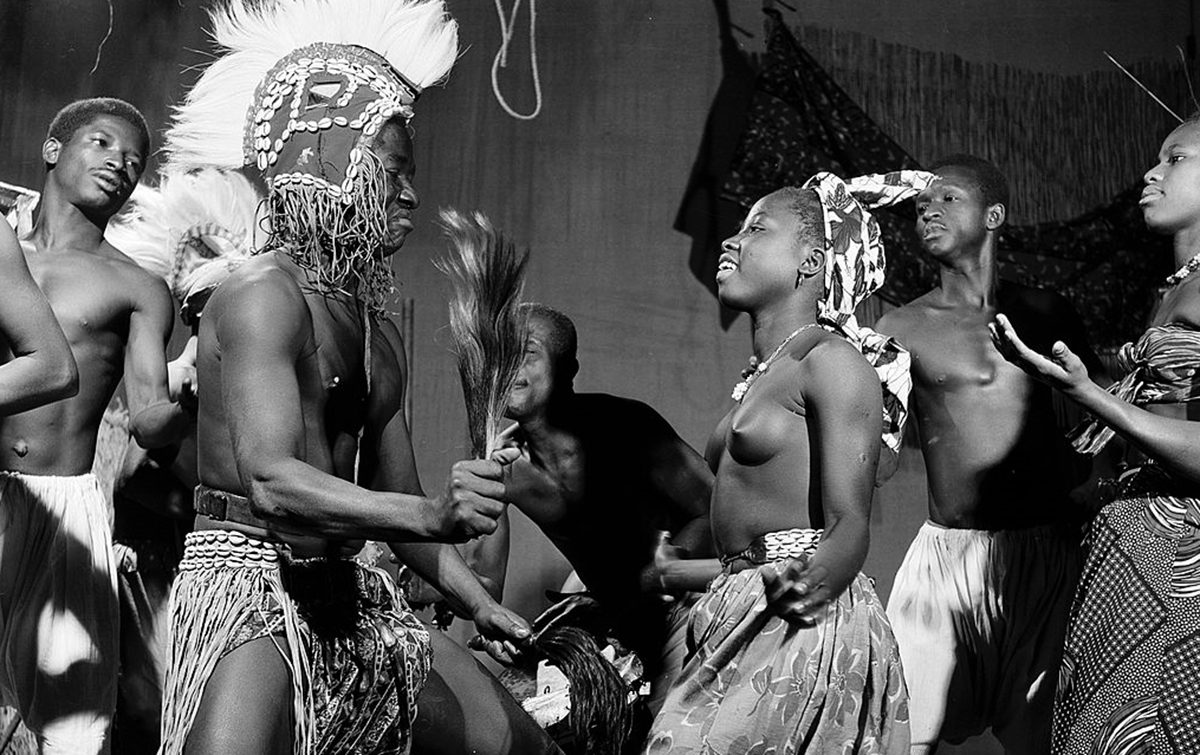

Although not exactly in the tradition of the risqué burlesque shows which had become popular in the 1950s at the Chelsea Palace (‘We went once a week,’ Quant once wrote, ‘the Chelsea Palace chorus girls wore very naughty fur bikini knickers.’), Chelsea at Nine became the first television programme to feature bare breasts on British television, albeit accidentally. The African dance group called the Ballets Africains had rehearsed earlier in the day fully clothed and no one checked what they were going to be wearing for their actual performance. Bruce Grimes, an art director on the show, was in the control room at the time and remembered that, ‘Suddenly all the cameras started pointing at the floor or on odd bits of scenery: The director was tearing his hair out, and the cameraman said, “Well, they’ve got nothing on, they’ve got bare tits.” The producer was there, and the director just said, “What do we do? Do you pull it, or what?” And the producer, you know, he had seconds to make up his mind, said, “Well, we’ll call it ‘ethnic’. Go for it.” So the director said, “Alright, lift the cameras up, show what’s going on.” And it went out. There was a hell of a fuss, you know.’

‘Don’t clap too loud, we’re all in a very old building,’ said Archie Rice in The Entertainer, but the Chelsea Palace was only sixty-three years old when it was demolished by developers in 1966, soon after Granada had vacated the premises. ‘A squalid block of shops replaced it,’ said John Osborne years later. One of which, although not particularly squalid, was a branch of Heal’s. From 2015, however, the building has become a Metro Bank.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.