In 1886, Anton Chekhov (1860-1904) wrote a letter to his artist older brother of two years Nikolai. He wanted Nikolai to kick his alcoholism and write. His advise failed. Three years later, Nikolai, an alcoholic, was dead. After a long appeal to his brother’s sensibilities, in which he reminds him of his talent, Chekhov tells him the remedy of his malaise is to be cultured. He outlines his 8 Ways to Be Civilized.

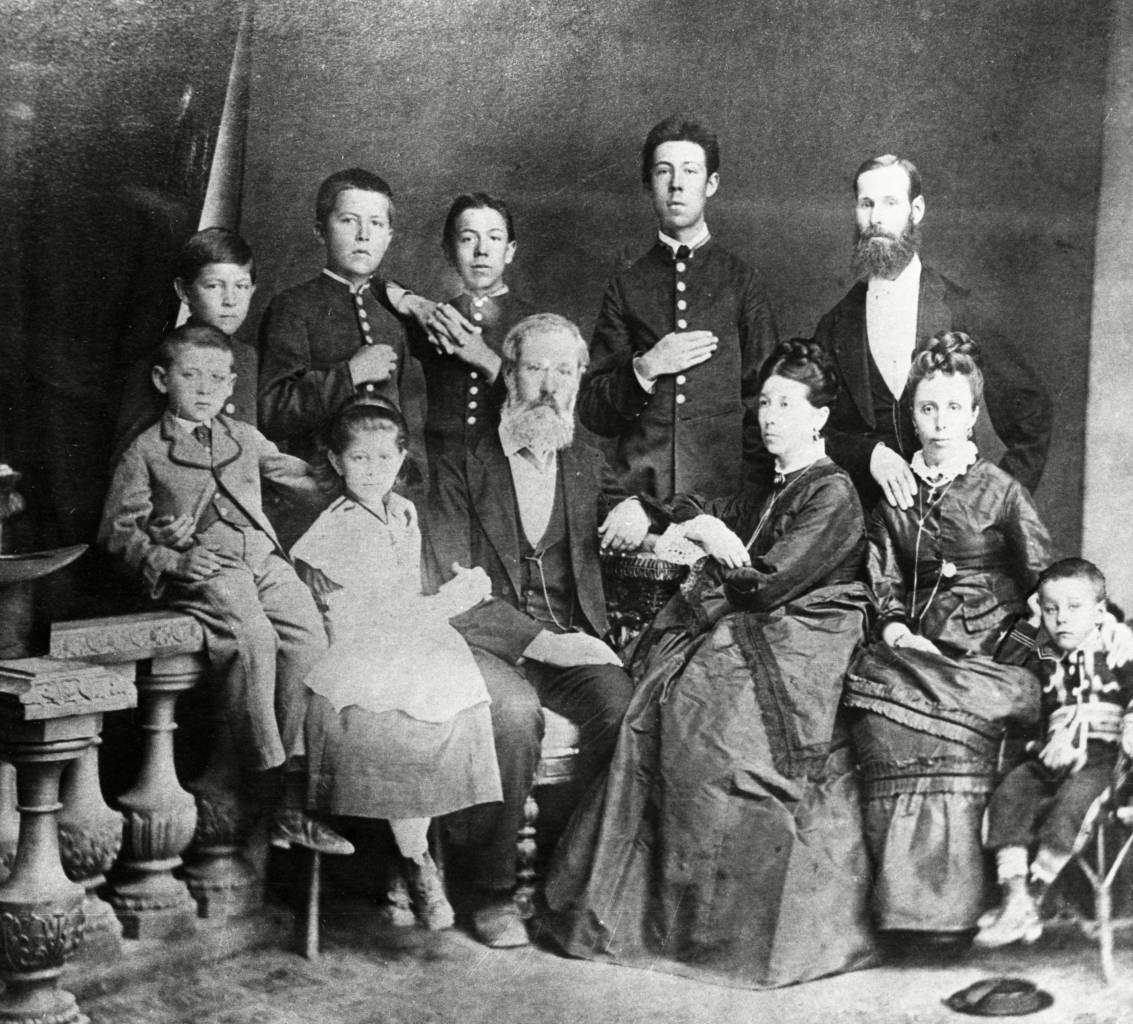

Chekhov family portrait, in the center, sitting, are the parents, Pavel and Yevgenia Chekhov, on the left are Mikhail and Maria, on the right is aunt Lyudmila with her son Georgy, standing (from left) are Ivan, Anton, Nikolai, Alexander, and uncle Mitrofan, 1874 or 1875.

Moscow, March, 1886

My little Zabelin,

I’ve been told that you have taken offense at gibes Schechtel and I have been making. The faculty of taking offense is the property of noble souls alone, but even so, if it is all right to laugh at Ivanenko, me, Mishka and Nelly, then why is it wrong to laugh at you? It’s unfair. However, if you’re not joking and really do feel you’ve been offended, I hasten to apologize.

People only laugh at what’s funny or what they don’t understand. Take your choice.

The latter of course is more flattering, but—alas!—to me, for one, you’re no riddle. It’s not hard to understand someone with whom you’ve shared the delights of Tatar caps, Voutsina, Latin and, finally, life in Moscow. And besides, your life is psychologically so uncomplicated that even a nonseminarian could understand it. Out of respect for you let me be frank. You’re angry, offended…but it’s not because of my gibes or of that good-natured chatterbox Dolgov. The fact of the matter is that you’re a decent person and you realize that you’re living a lie. And, whenever a person feels guilty, he always looks outside himself for vindication: the drunk blames his troubles, Putyata blames the censors, the man who bolts from Yakimanka Street with lecherous intent blames the cold in the living room or gibes, and so on. If I were to abandon the family to the whims of fate, I would try to find myself an excuse in Mother’s character or my blood spitting or the like. It’s only natural and pardonable. It’s human nature, after all. And you’re quite right to feel you’re living a lie. If you didn’t feel that way, I wouldn’t have called you a decent person. When decency goes, well, that’s another story. You become reconciled to the lie and stop feeling it.

You’re no riddle to me, and it is also true that you can be wildly ridiculous. You’re nothing but an ordinary mortal, and we mortals are enigmatic only when we’re stupid, and we’re ridiculous forty-eight weeks of the year. Isn’t that so?

You often complain to me that people “don’t understand” you. But even Goethe and Newton made no such complaints. Christ did, true, but he was talking about his doctrine, not his ego. People understand you all too well. If you don’t understand yourself, then it’s nobody else’s fault.

As your brother and intimate, I assure you that I understand you and sympathize with you from the bottom of my heart. I know all your good qualities like the back of my hand. I value them highly and have only the greatest respect for them. If you like, I can even prove how I understand you by enumerating them. In my opinion you are kind to the point of fault, magnanimous, unselfish, you’d share your last penny, and you’re sincere. Hate and envy are foreign to you, you are open-hearted, you are compassionate with man and beast, you are not greedy, you do not bear grudges, and you are trusting. You are gifted from above with something others lack: you have talent. This talent places you above millions of people, for there is only one artist for every two million people on earth. It places you in a very special position: you could be a toad or a tarantula and you would still be respected, because talent is its own excuse.

You have only one failing, the cause of the lie you’ve been living, your troubles, and your intestinal catarrh. It’s your extreme lack of culture. Please forgive me, but veritas magis amicitiae. The thing is, life lays down certain conditions. If you want to feel at home among intellectuals, to fit in and not find their presence burdensome, you have to have a certain amount of breeding. Your talent has brought you into their midst. You belong there, but…you seem to yearn escape and feel compelled to waver between the cultured set and your next-door neighbors. It’s the bourgeois side of you coming out, the side raised on birch thrashings beside the wine cellar and handouts, and it’s hard to overcome, terribly hard.

To my mind, civilized people ought to satisfy the following conditions:

1. They respect the individual and are therefore always indulgent, gentle, polite and compliant. They do not throw a tantrum over a hammer or a lost eraser. When they move in with somebody, they do not act as if they were doing him a favor, and when they move out, they do not say, “How can anyone live with you!” They excuse noise and cold and overdone meat and witticisms and the presence of others in their homes.

2. Their compassion extends beyond beggars and cats. They are hurt even by things the naked eye can’t see. If for instance, Pyotr knows that his father and mother are turning gray and losing sleep over seeing their Pyotr so rarely (and seeing him drunk when he does turn up), then he rushes home to them and sends his vodka to the devil. They do not sleep nights the better to help the Polevayevs, help pay their brothers’ tuition, and keep their mother decently dressed.

3. They respect the property of others and therefore pay their debts.

4. They are candid and fear lies like the plague. They do not lie even about the most trivial matters. A lie insults the listener and debases him in the liar’s eyes. They don’t put on airs, they behave in the street as they do at home, and they do not try to dazzle their inferiors. They know how to keep their mouths shut and they do not force uninvited confidences on people. Out of respect for the ears of others they are more often silent than not.

5. They do not belittle themselves merely to arouse sympathy. They do not play on people’s heartstrings to get them to sigh and fuss over them. They do not say, “No one understands me!” or “I’ve squandered my talent on trifles!” because this smacks of a cheap effect and is vulgar, false and out-of-date.

6. They are not preoccupied with vain things. They are not taken in by such false jewels as friendships with celebrities, handshakes with drunken Plevako, ecstasy over the first person they happen to meet at the Salon de Varietes, popularity among the tavern crowd. They laugh when they hear, “I represent the press,” a phrase befitting only Rodzeviches and Levenbergs. When they have done a penny’s worth of work, they don’t try to make a hundred rubles out of it, and they don’t boast over being admitted to places closed to others. True talents always seek obscurity. They try to merge with the crowd and shun all ostentation. Krylov himself said that an empty barrel has more chance of being heard than a full one.

7. If they have talent, they respect it. They sacrifice comfort, women, wine and vanity to it. They are proud of their talent, and so they do not go out carousing with trade-school employees or Skvortsov’s guests, realizing that their calling lies in exerting an uplifting influence on them, not in living with them. What is more, they are fastidious.

8. They cultivate their aesthetic sensibilities. They cannot stand to fall asleep fully dressed, see a slit in the wall teeming with bedbugs, breathe rotten air, walk on a spittle-laden floor or eat off a kerosene stove. They try their best to tame and ennoble their sexual instinct… What they look for in a woman is not a bed partner or horse sweat, […] not the kind of intelligence that expresses itself in the ability to stage a fake pregnancy and tirelessly reel off lies. They—and especially the artists among them—require spontaneity, elegance, compassion, a woman who will be a mother… They don’t guzzle vodka on any old occasion, nor do they go around sniffing cupboards, for they know they are not swine. They drink only when they are free, if the opportunity happens to present itself. For they require a mens sana in corpore sano.

And so on. That’s how civilized people act. If you want to be civilized and not fall below the level of the milieu you belong to, it is not enough to read The Pickwick Papers and memorize a soliloquy from Faust. It is not enough to hail a cab and drive off to Yakimanka Street if all you’re going to do is bolt out again a week later.

You must work at it constantly, day and night. You must never stop reading, studying in depth, exercising your will. Every hour is precious.

Trips back and forth to Yakimanka Street won’t help. You’ve got to drop your old way of life and make a clean break. Come home. Smash your vodka bottle, lie down on the couch and pick up a book. You might even give Turgenev a try. You’ve never read him.

You must swallow your pride. You’re no longer a child. You’ll be thirty soon. It’s high time!

I’m waiting…We’re all waiting…

Yours,

A. Chekhov

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.