Anthony Burgess, polymath, slang dictionary compiler, creator of other world’s and author of A Clockwork Orange, selected the Top 5 Dystopian Novel for his book Ninety-Nine Novels: The Best in English since 1939 – A Personal Choice. He did so, appropriately enough, in 1984, which is, of course, the title of George Orwell’s book, perhaps the best-known dystopian fiction of the 20th Century. Burgess’s novel 1985 (1978) was a tribute to Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four. It augmented Burgess’ two other dystopian novels, The Wanting Seed and A Clockwork Orange (both 1962).

Burgess wrote of 1949:

Let me tell you about 1949, when I was reading Orwell’s book about 1948. The war had been over four years and we had missed the dangers – buzz-bombs, for instance. You can put up with privations when you have the luxury of danger. But now we had worse privations than during the war, and they seemed to get worse every week. The meat ration was down to a couple of slices of fatty corned beef. One egg a month, and the egg was usually bad. I seem to remember you could get cabbages easily enough. Boiled cabbage was a redolent staple of the British diet. You couldn’t get cigarettes. Razor blades had disappeared from the market. I remember a short story that began, ‘It was the fifty-fourth day of the new razor blade’ – there’s comedy for you. You saw the effects of German bombing everywhere, with London pride and loosestrife growing brilliantly in the craters. It’s all in Orwell.

Books like Nineteen Eighty-Four act like a siren, Burgess attested:

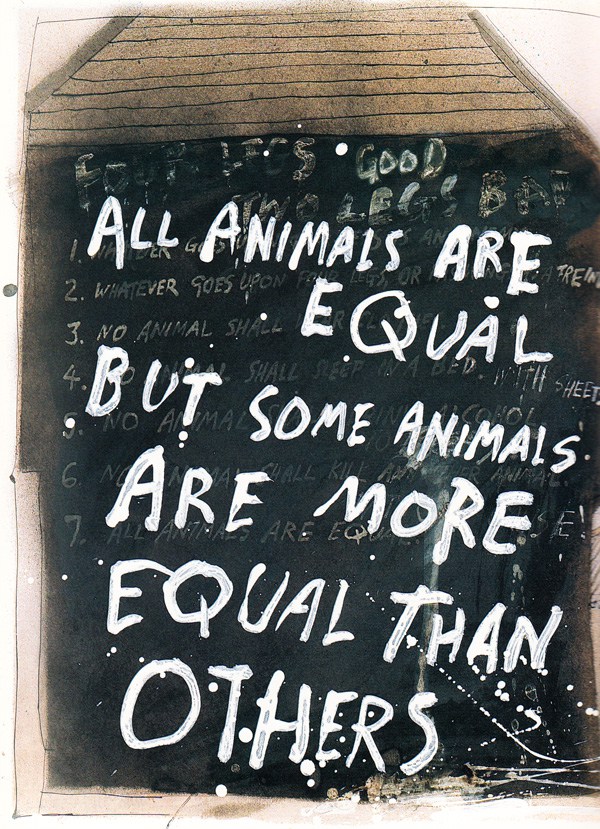

Freedom is so painful an obligation that there will always be some who would prefer to abandon it. The virtue of a book like Nineteen Eighty-Four — or Zamyatin’s We, or Huxley’s Brave New World, or Wells’s When the Sleeper Awakes, or David Karp’s One, or even More’s Utopia – is its capacity to remind us that the freedom of responsible human beings is not that of proles or animals. If 1984 is no more terrifying a year than 1983, that will partly be because Nineteen Eighty-Four has done its work’.

As for what dystopia is, this is a good potted history:

The term ‘utopia’, literally meaning ‘no place’, was coined by Thomas More in his book of the same title. Utopia (1516) describes a fictional island in the Atlantic ocean and is a satire on the state of England. The English philosopher John Stuart Mill coined ‘Dystopia’, meaning ‘bad place’, in 1868 as he was denouncing the government’s Irish land policy. He was inspired by More’s writing on utopia.

So here are Anthony Burgess’s Top Five Dystopian Novels (1939-1984):

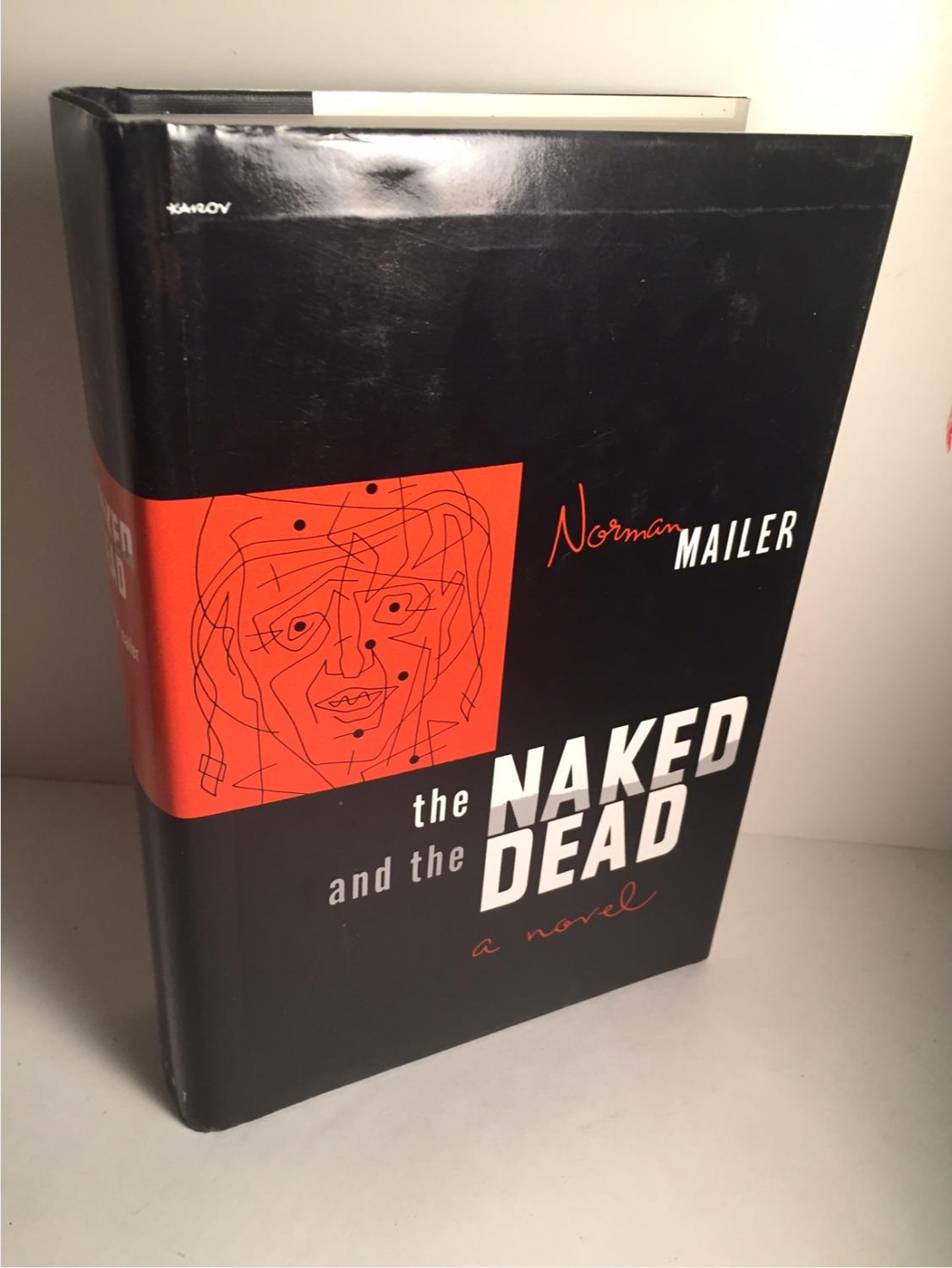

The Naked and the Dead by Norman Mailer

The British edition of this novel appeared in 1949, the same year as Nineteen Eighty-Four, and percipient critics saw that the two books had in common the theme of a new doctrine of power. Winston Smith’s torturer in Nineteen Eighty-Four (q.v.) presents his victim-pupil with an image of the future — a boot stamping on a face for ever and ever. General Cummings in Mailer’s novel tells Lieutenant Hearn to see the Army as ‘a preview of the future’, and it is a future very like Orwell’s, its only morality ‘a power morality’. He, representing the higher command, and Sergeant Croft, the lower, are fighting fascism but are themselves fascists and well aware of it. Hearn, the weak liberal who will not, despite his weakness, submit to the sadism of Cummings, is destroyed by his general through his sergeant. Cummings the strategist plans while Croft the fighting leader executes; Hearn, who represents a doomed order of human decency, is crushed between two extremes of the new power morality.

The narrative presents, with great accuracy and power, the agony of American troops in the Pacific campaign. A representative group of lower-class Americans forms the reconnaissance patrol sent before a proposed attack on the Japanese-held island of Anopopei. We smell the hot dishrag effluvia of the jungle and the sweat of the men. Of this body of typical Americans, however, despite the vivid realization of skin, muscle and nerves, only Hearn and Croft emerge as living individuals. With the men there is an over-zealous desire to range the racial and regional gamut of the United States — the Jew, the Pole, the Texan, and so on. Mailer blocks in their backgrounds with a device borrowed from John Dos Passos — the episodic fragmentary impressionistic flashback, which he calls ‘The Time Machine’. This is something of a mill or grinder: it seems to reduce the pasts of all the subsidiary characters to the common flour of sexual preoccupation.

The futility of war is well presented. The island to be captured has no strategic importance. The spirit of revolt among the men is stirred by an accident: the patrol stumbles into a hornets’ nest and runs away, dropping weapons and equipment, the naked leaving the dead behind them. An impulse can contain seeds of human choice: we have not yet been turned entirely into machines. Mailer’s pessimism was to come later — in The Deer Park and Barbary Shore and An American Dream — but here, with men granting themselves the power to opt out of the collective suicide of war, there is a heartening vision of hope. This is an astonishingly mature book for a twenty-five-year-old novelist. It remains Mailer’s best, and certainly the best war novel to emerge from the United States.

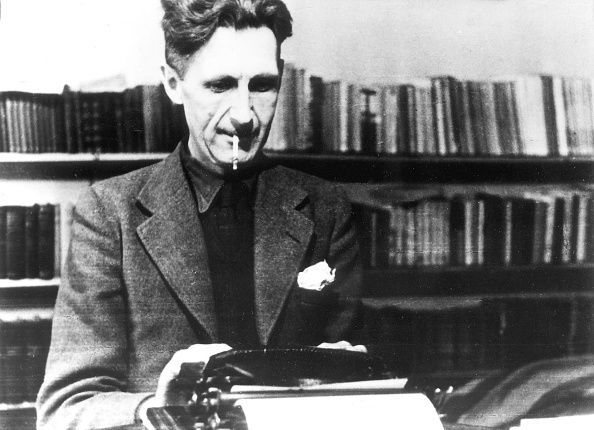

Nineteen Eighty-Four by George Orwell

This is one of the few dystopian or cacotopian visions which have changed our habits of thought. It is possible to say that the ghastly future Orwell foretold has not come about simply because he foretold it: we were warned in time. On the other hand, it is possible to think of this novel as less a prophecy than the comic joining together of two disparate things — an image of England as it was in the immediate post-war era, a land of gloom and shortages, and the bizarrely impossible notion of British intellectuals taking over the government of the country (and, for that matter, the whole of the English-speaking world). The world is divided into three superstates — Oceania, Eurasia and Eastasia, two of which, in a perpetual shifting of alliances, are always at war with each other. Britain is part of Oceania and is called Airstrip One. Winston Smith, a citizen of its capital, has been brought up, like everyone else, to accept the monolithic rule of Big Brother — a mythical and hence immortal being, the titular head of an oligarchy which subscribes to a philosophy called, ironically, English Socialism or Ingsoc. Only the ‘proles’, the masses, are free, free because their minds are too contemptible to be controlled; members of the Party are under perpetual surveillance from the Thought Police. Winston, the last man to possess any concept of freedom (the title Orwell originally envisaged for the book was The Last Man in Europe), revolts against Big Brother, but he is arrested and — through torture allied to metaphysical re-education — rehabilitated. He learns the extent of the power of the Party, its limitless ability to control thought, even speech. Newspeak is a variety of English which renders it impossible to express an heretical thought; ‘doublethink’ is a technique which enables the Party to impress its own image on external reality, so that ‘2 + 2 = 5’ can be a valid equation. The State is eternal and absolute, the only repository of truth. The last free man yields, of his own free will (this is important — there is no brainwashing in Orwell’s cacotopia), his whole being to it.

Aldous Huxley admitted, in re-introducing his Brave New World (1932 — outside our scope) to the post-war age, that Orwell presented a more plausible picture of the future than he himself had done, with his image of a world made stable and happy through chemical conditioning. Whether Orwell himself, were he alive today, would withdraw any part of his prophecy (if it is a prophecy) we do not know. he was mortally sick when he made it, admitting that it was a dying man’s fantasy. The memorable residue of Nineteen Eighty-Four, as of Brave New World, is the fact of the tenuousness of human freedom, the vulnerability of the human will, and the genuine power of applied science.

Nineteen Eighty-Four is not a perfect novel, and some would argue that it is too didactic to be considered a novel at all. Orwell’s best work is to be found in the four posthumously published volumes of critical and polemical essay, and in his fable Animal Farm (1945). This last is certainly not a novel and hence cannot be considered for inclusion here.

Facial Justice by L.P. Hartley

England is recovering from World War III. There have been nuclear attacks and society has only recently emerged from skulking in caves. The new state is afflicted with a profound sense of guilt, and every one of its citizens is named after a murderer. Thus the heroine has been christened Jael 97. An attempt to formulate a new morality results in an outlawing of envy and the competitive urge. There must be no exceptional beauty, neither in body (which penitential sackcloth covers anyway) nor in face. A girl who feels herself ‘facially underprivileged’ can be fitted with a standard Beta face, neither ugly nor beautiful. Jael 97 is facially overprivileged: her beauty must be reduced to a drab norm. But, like the heroes and heroines of all cacotopian novels, she is an eccentric. Seeing for the first time the west tower of Ely Cathedral, one of the few lofty structures left unflattened by the war, she experiences a transport of ecstasy and wishes to cherish her beauty. Her revolt against the regime results in no brutal reimposition of conformity — only in the persuasions of sweet reason. This is no Orwellian future. It is a world incapable of the dynamic of tyranny. Even the weather is always cool and grey, with no room for wither fire or ice. The state motto is ‘Every valley shall be exalted.’ This is a brilliant projection of tendencies already apparent in the post-war British welfare state but, because the book lacks the expected horrors of cacotopian fiction, it has met less appreciation than Nineteen Eighty-Four. That Hartley was a fine writer with a strong moral sense had already been confirmed by his Eustace and Hilda trilogy, where, as is prefigured in the first book of the three, The Shrimp and the Anemone, a young man and woman are locked in a dance of death which they are powerless to halt. The anemone Hilda eats the shrimp Eustace: destruction is part of the law of nature. I hesitated to prefer Facial Justice to the trilogy, but on points of imagination and originality it seems to win.

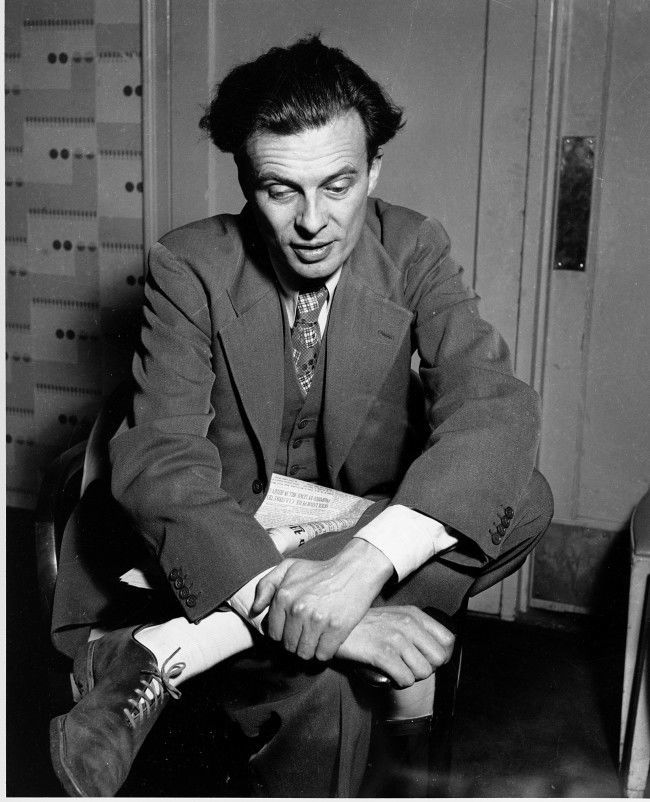

Island by Aldous Huxley

As with so much of Huxley’s later fiction, one is not sure whether of not to call this book a true novel. It is less concerned with telling a tale than with presenting an attitude to life, it is weak on characterization but strong on talk, crammed with ideas and uncompromisingly intellectual. Huxley shows us an imaginary tropical island where the good life can be cultivated for the simple reason that the limitations and potentialities of man are thoroughly understood. He presents a conspectus of this life, ranging from modes of sexual behaviour to the technique of dying. Nobody is scientifically conditioned to be happy: this new world is really brave. It has learned a great deal from Eastern religion and philosophy, but it is prepared to take the best of Western science, technology and art. The people themselves are a sort of ideal Eurasian race, equipped with fine bodies and Huxleyan brains, and they have read all the books that Huxley has read.

All this sounds like an intellectual game, a hopeless dream in a foundering world, but Huxley was always enough of a realist to know that there is a place for optimism. Indeed, no teacher can be a pessimist, and Huxley was essentially a teacher. In Island the good life is eventually destroyed by a brutal, stupid, materialistic young raja who wants to exploit the island’s mineral resources. The armoured cars crawl through, the new dictator makes speeches about Progress, Values, Oil, True Spirituality, but ‘disregarded in the darkness, the fact of enlightenment remained’. The mynah birds fly about, crying the word that means enlightenment: ‘Karuna. Karuna.’

For forty years his readers forgave Huxley for turning the novel form into an intellectual hybrid — the teaching more and more overlaid the proper art of the story-teller. Having lost him, we now find nothing to forgive. No novels more stimulating, exciting or genuinely enlightening came out of the post-Wellsian time. Huxley more than anyone helped to equip the contemporary novel with a brain.

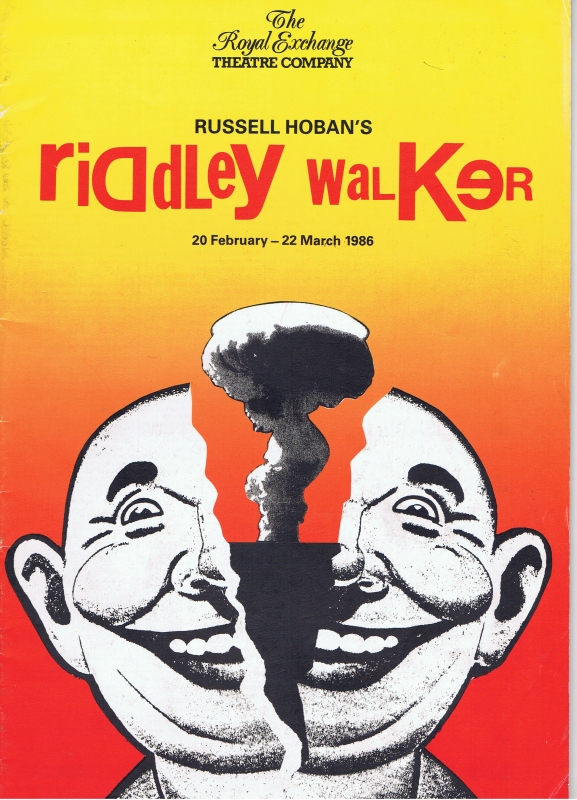

Riddley Walker by Russell Hoban

‘On my naming day when I come 12 I gone front spear and kilt a wyld boar he parbly ben the last wyld pig on the Bundel Downs and how there hadnt ben none for a long time befor him nor I aint lookin to see none agen.’ So the book begins. It is a dangerous and difficult dialect of Hoban’s own invention, but it is altogether appropriate to an as yet unborn England — one that, after nuclear war, is trying to organize tribal culture after the total destruction of a centralized industrial civilization. The past has been forgotten, and even the art of making fire has to be relearned. The novel is remarkable not only for its language but for its creation of a whole set of rituals, myths and poems. Hoban has built a whole world from scratch. Sometimes these strange English people find remnants of old machines, but they have forgotten their meaning. ‘Some of them ther shells ben broak open you cud see girt shyning weals like jynt mil stoans only smoov.’ The lost past is contained in a kind of sacred book called The Eusa Story, whose first chapter is this: ‘Wen Mr Clevver wuz Big Man uv Inland they had evere thing clever. They had boats in the ayr & picters on the win & evere thing lyk that. Eusa wuz a noing man vere quik he cud tern his han tu enne thing. He wuz werkin for Mr Clevver wen theyr cum enemes aul roun & maykni Warr. Eusa sed tu Mr Clevver, Now wewl nead masheans uv Warr. Wewl nead boats that go on the water & boats that go in the ayr as wel & wewl nead Berstin Fyr.’ Finally they make use of ‘the Littl Shynin Man the Addom he runs in the wud’. This novel could not expect to be popular: it is not an easy read like The Carpetbaggers. But it seems to me a permanent contribution to literature.

And so to the full list, a tribute to the novel, “a powerful literary form which is capable of reaching out into the real world and modifying it. It is a form which even the nonliterary had better take seriously.”

And so to the big list.

Ninety-Nine Novels: The Best in English since 1939 – A Personal Choice, by Anthony Burgess (1984).

Burgess writes in the introduction:

“You have here brief accounts of ninety-nine fine novels produced between 1939 and now.

“In my time I have read a lot of novels in the way of duty; I have read a great number for pleasure as well. I am, I think, qualified to compile a list like the one that awaits you a few pages ahead. The ninety-nine novels I have chosen I have chosen with some, though not with total, confidence. Reading pleasure has not been the sole criterion. I have concentrated mainly on works which have brought something new – in technique or view of the world–to the form.”

1930s

1939 – Henry Green – Party Going (1939)

1939 – Aldous Huxley – After Many a Summer (1939)

1939 – James Joyce – Finnegans Wake (1939)

1939 – Flann O’Brien – At Swim-Two-Birds (1939)1940s

1940 – Graham Greene – The Power and the Glory (1940)

1940 – Ernest Hemingway – For Whom the Bell Tolls (1940)

1940 – C. P. Snow – Strangers and Brothers (1940)

1941 – Rex Warner – The Aerodrome (1941)

1944 – Joyce Cary – The Horse’s Mouth (1944)

1944 – W. Somerset Maugham – The Razor’s Edge (1944)

1945 – Evelyn Waugh – Brideshead Revisited (1945)

1946 – Mervyn Peake – Titus Groan (1946)

1947 – Saul Bellow – The Victim (1947)

1947 – Malcolm Lowry – Under the Volcano (1947)

1949 – Elizabeth Bowen – The Heat of the Day (1949)

1948 – Graham Greene – The Heart of the Matter (1948)

1948 – Aldous Huxley – Ape and Essence (1948)

1948 – Nevil Shute – No Highway (1948)

1948 – Norman Mailer – The Naked and the Dead (1948)

1949 – George Orwell – Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949)

1949 – William Sansom – The Body (1949)1950s

1950 – William Cooper – Scenes from Provincial Life (1950)

1950 – Budd Schulberg – The Disenchanted (1950)

1951 – Anthony Powell – A Dance to the Music of Time (1951)

1951 – J. D. Salinger – The Catcher in the Rye (1951)

1951 – Henry Williamson – A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight (1951)

1951 – Herman Wouk – The Caine Mutiny (1951)

1952 – Ralph Ellison – Invisible Man (1952)

1952 – Ernest Hemingway – The Old Man and the Sea (1952)

1952 – Mary McCarthy – The Groves of Academe (1952)

1952 – Flannery O’Connor – Wise Blood (1952)

1952 – Evelyn Waugh – Sword of Honour (1952)

1953 – Raymond Chandler – The Long Goodbye (1953)

1954 – Kingsley Amis – Lucky Jim (1954)

1957 – John Braine – Room at the Top (1957)

1957 – Lawrence Durrell – The Alexandria Quartet (1957)

1957 – Colin MacInnes – The London Novels (1957)

1957 – Bernard Malamud – The Assistant (1957)

1958 – Iris Murdoch – The Bell (1958)

1958 – Alan Sillitoe – Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1958)

1958 – T. H. White – The Once and Future King (1958)

1959 – William Faulkner – The Mansion (1959)

1959 – Ian Fleming – Goldfinger (1959)1960s

1960 – L. P. Hartley – Facial Justice (1960)

1960 – Olivia Manning – The Balkan Trilogy (1960)

1961 – Ivy Compton-Burnett – The Mighty and Their Fall (1961)

1961 – Joseph Heller – Catch-22 (1961)

1961 – Richard Hughes – The Fox in the Attic (1961)

1961 – Patrick White – Riders in the Chariot (1961)

1961 – Angus Wilson – The Old Men at the Zoo (1961)

1962 – James Baldwin – Another Country (1962)

1962 – Aldous Huxley – Island (1962)

1962 – Pamela Hansford Johnson – An Error of Judgement (1962)

1962 – Doris Lessing – The Golden Notebook (1962)

1962 – Vladimir Nabokov – Pale Fire (1962)

1963 – Muriel Spark – The Girls of Slender Means (1963)

1964 – William Golding – The Spire (1964)

1964 – Wilson Harris – Heartland (1964)

1964 – Christopher Isherwood – A Single Man (1964)

1964 – Vladimir Nabokov – The Defense (1964)

1964 – Angus Wilson – Late Call (1964)

1965 – John O’Hara – The Lockwood Concern (1965)

1965 – Muriel Spark – The Mandelbaum Gate (1965)

1966 – Chinua Achebe – A Man of the People (1966)

1966 – Kingsley Amis – The Anti-Death League (1966)

1966 – John Barth – Giles Goat-Boy (1966)

1966 – Nadine Gordimer – The Late Bourgeois World (1966)

1966 – Walker Percy – The Last Gentleman (1966)

1967 – R. K. Narayan – The Vendor of Sweets (1967)

1968 – J. B. Priestley – The Image Men (1968)

1968 – Mordecai Richler – Cocksure (1968)

1968 – Keith Roberts – Pavane (1968)

1969 – John Fowles – The French Lieutenant’s Woman (1969)

1969 – Philip Roth – Portnoy’s Complaint (1969)1970s

1970 – Len Deighton – Bomber (1970)

1973 – Michael Frayn – Sweet Dreams (1973)

1973 – Thomas Pynchon – Gravity’s Rainbow (1973)

1975 – Saul Bellow – Humboldt’s Gift (1975)

1975 – Malcolm Bradbury – The History Man (1975)

1976 – Robert Nye – Falstaff (1976)

1977 – Erica Jong – How to Save Your Own Life (1977)

1977 – James Plunkett – Farewell Companions (1977)

1977 – Paul Mark Scott – Staying On (1977)

1978 – John Updike – The Coup (1978)

1979 – J. G. Ballard – The Unlimited Dream Company (1979)

1979 – Bernard Malamud – Dubin’s Lives (1979)

1979 – Brian Moore – The Doctor’s Wife (1976)

1979 – V. S. Naipaul – A Bend in the River (1979)

1979 – William Styron – Sophie’s Choice (1979)1980s

1980 – Brian Aldiss – Life in the West (1980)

1980 – Russell Hoban – Riddley Walker (1980)

1980 – David Lodge – How Far Can You Go? (1980)

1980 – John Kennedy Toole – A Confederacy of Dunces (1980)

1981 – Alasdair Gray – Lanark (1981)

1981 – Alexander Theroux – Darconville’s Cat (1981)

1981 – Paul Theroux – The Mosquito Coast (1981)

1981 – Gore Vidal – Creation (1981)

1982 – Robertson Davies – The Rebel Angels (1982)

1983 – Norman Mailer – Ancient Evenings (1983)

Via: The Anthony Burgess Foundation, Open Culture, Neglected Books

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.