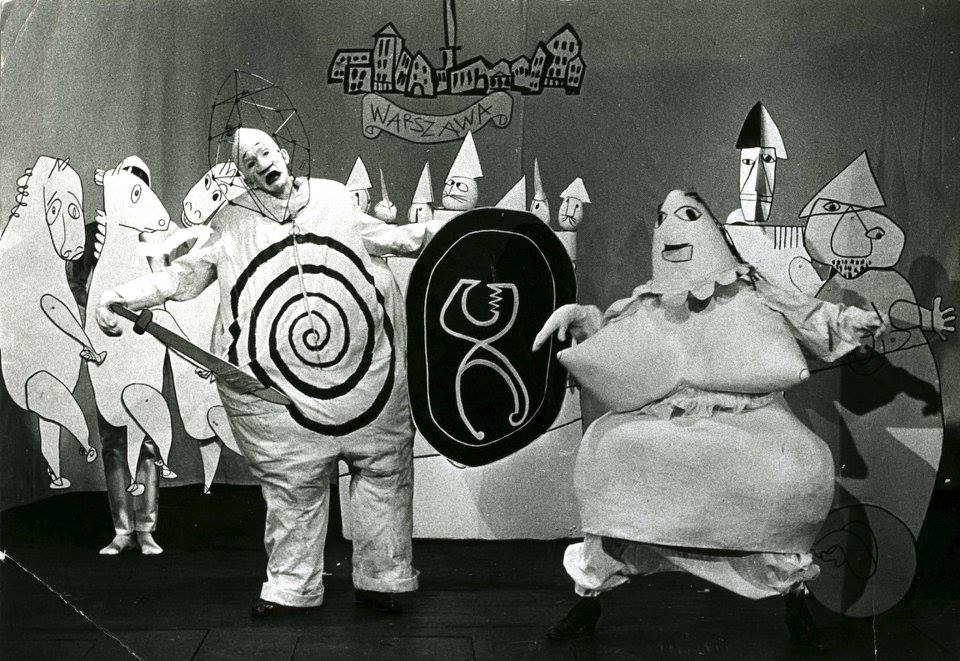

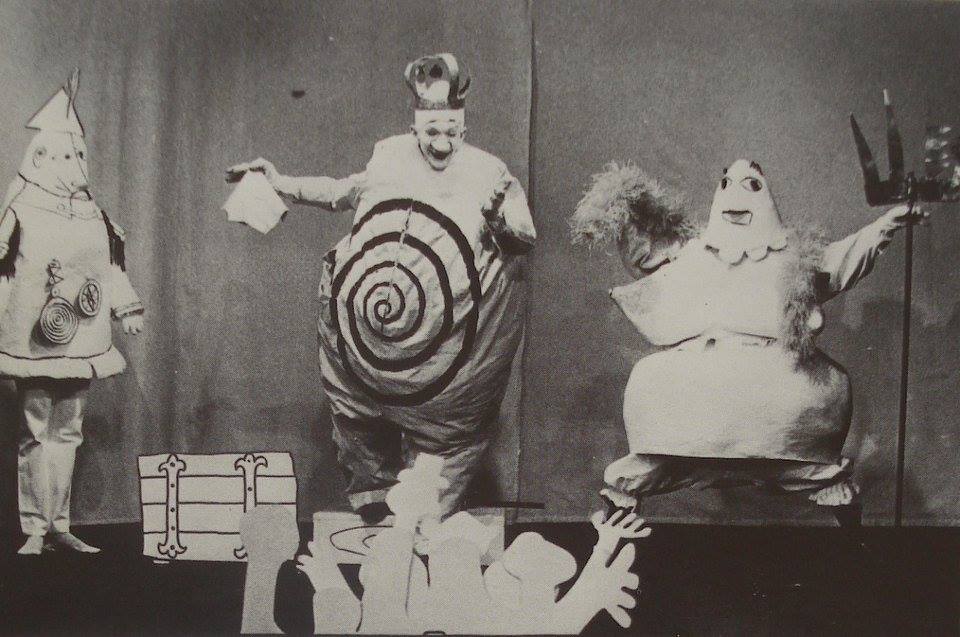

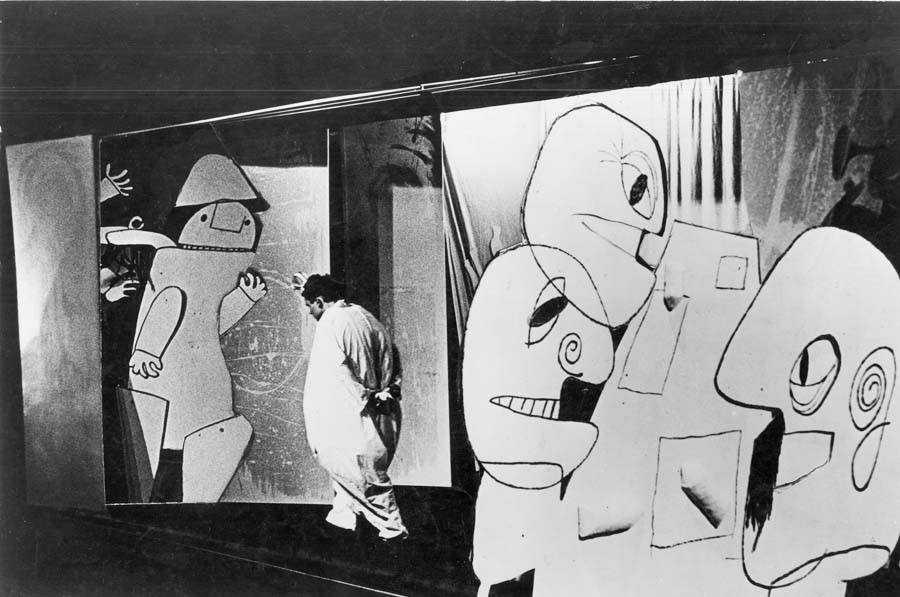

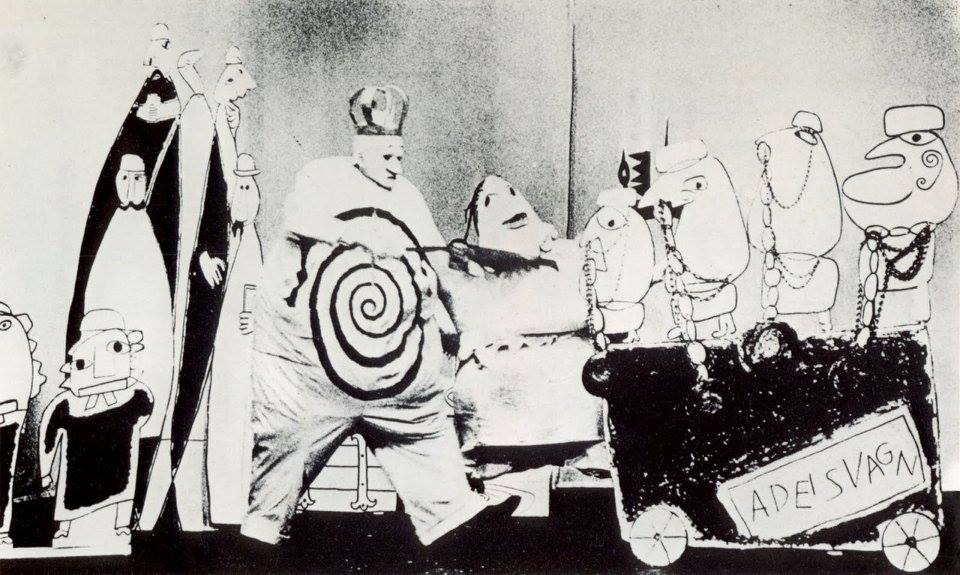

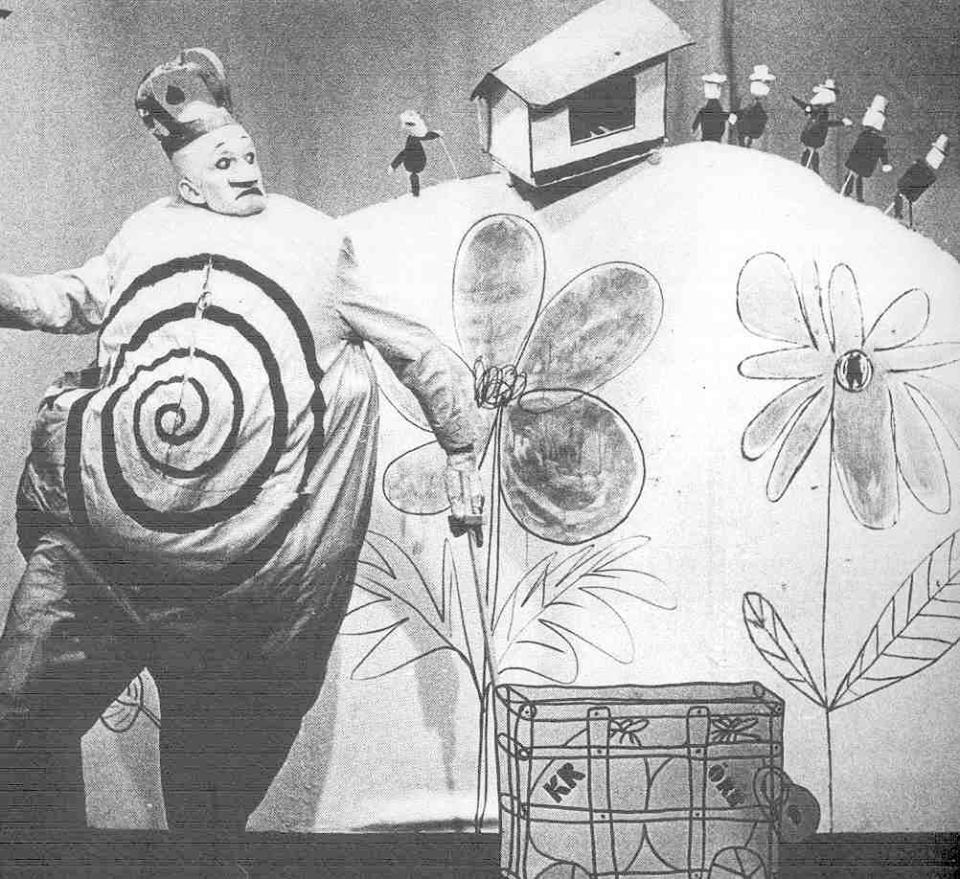

Michael Meschke’s adaptation of Alfred Jarry’s scatological and chaotic play Ubu Roi was performed at the Marionetteatern performing arts theatre, Stockholm, in 1964. Costumes, sets and puppets were designed and created by Franciska and Stefan Themerson. This post is illustrated by photographs from Meschke’s show.

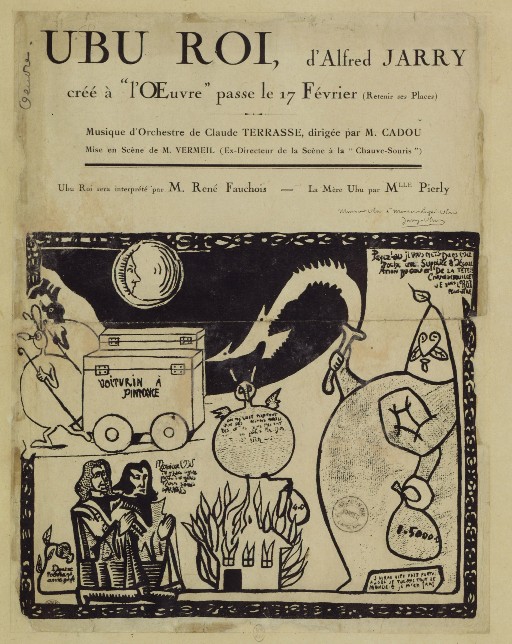

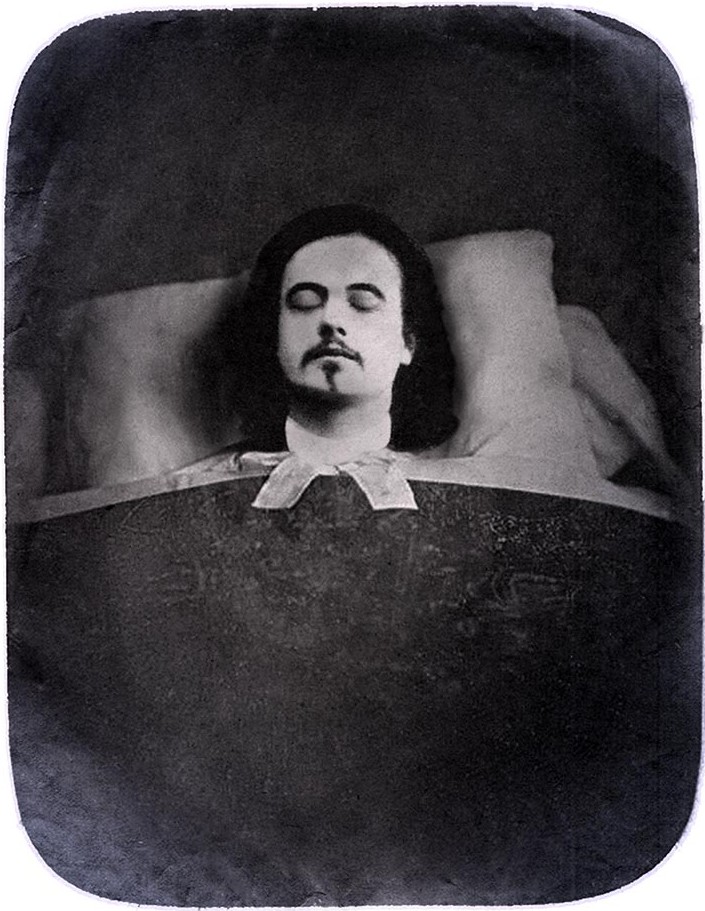

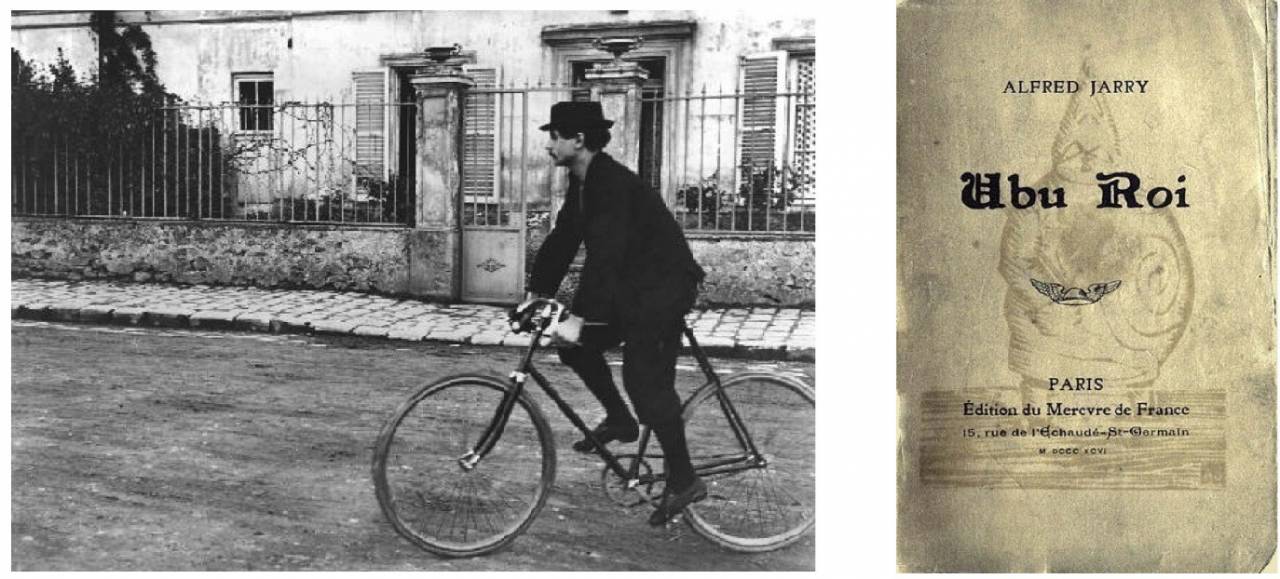

Ubu Roi was first performed in Paris at the Théâtre de l’Œuvre on December 10, 1896. Jarry, only twenty-three at the time, had come to Paris five years before to live on a small family inheritance. He frequented the literary salons of the time and began to write. It didn’t take long for his inheritance to disappear and he soon lapsed into a chaotic and anarchic existence in which he met the demands of day-to-day life with self-conscious buffoonery. He died in a state of utter destitution and alcoholism. Ubu Roi, however, was an innovative, avant-garde satire on power, greed, and malfeasance. It caused a stir, provoking riots in the theatre and a national scandal and Ubu Roi was banned after only two performances (one of which was the dress rehearsal). It really was that good.

The story, a re-telling of Shakespeare’s Macbeth, begins with Père Ubu (played by Firmin Gémier) exclaiming “Merdre”, which can be translated as ‘Shitsky!’ or ‘Shite!’.

The story than becomes a little oblique. The action centres on Ubu, a grotesque caricature based on Félix-Frédéric Hébert (14 January 1832 – 14 October 1918), Jarry’s physics teacher at a Rennes lycée – “la déformation par un potache d’un de ses professeurs qui représentait pour lui tout le grotesque qui fût au monde.”

We know something of Jarry’s unwitting muse. In June 1882 the school inspector noted: “M. Hébert’s speech is ponderous and muffled. His lessons lack both clarity and organization. His influence on his pupils is almost nil. He does not know how to impose his authority, nor how to get the slightest attention from his pupils.”

Might we feel a pang of sympathy for the lampooned teacher? Hold that thought as we deliver an aside full of context:

Finally, in 1892 and after eleven years at Rennes, he was persuaded to retire, on reaching the age of sixty.

A few years later the events of the Dreyfus Affair obliged his return to public service. Alfred Dreyfus had been the highest-ranking Jewish officer ever to serve in the French Army until, in 1894, a court martial found him guilty of passing military secrets to the Germans. After a ceremony of public denigration he was imprisoned on Devil’s Island under particularly arduous conditions. It soon became obvious that he was the victim of an anti-Semitic plot, and the “Affair” became the greatest political controversy of its day. Dreyfus’s second court martial, in 1899, happened to take place in Rennes; the courtroom was within the lycée building itself. He was again found guilty, and sentenced to an additional ten years in prison, even though the evidence brought against him at his first trial had been shown in the interim to have been forged. The verdict was so obviously unjust that the French President pardoned him anyway. Hébert was so outraged by this attempt, in his words, “to rehabilitate a justly condemned traitor” that he entered local politics and was elected a town councilor in 1900. Later the same year a local paper carried this report of a council meeting:

M. Hébert, by virtue of the seniority granted by his age, was called upon to preside over the meeting for just a few minutes; he took advantage of this to read to the new council the sort of address in which everything is a matter of “city-slickers, gangs of Jewish Freemasons, bribed government officials, the Flag, France, etc.” The council did not appear to be particularly gripped by this stale old claptrap, which was clumsily delivered by King Ubu.

The schoolboy joke made first by brothers Charles and Henry Morrin was taken up with gusto by their classmate, the 15-year-old Jarry.

Henri Hertz, another pupil at the school, has more to add:

Hébert was celebrated for the violent barracking he suffered and for the portentous manner with which he strove to placate his tormentors. He was not one to allow himself to be overcome straightaway, to be too quickly reduced to trembling abasement, not before attempting to defend himself with great blusterings of rage. Hardly ever, anyway. What we loved in him, what made him unique, and inspired a plethora of ingenious inventions aimed at stirring him up, was that we could look forward to beautiful tears, noble sobs, and ceremonious supplications.

Hébert’s torture passed through three phases, accompanied on his part by three physiognomies:

Entrance: wary, Hébert paused at the threshold of the classroom. His legs were so short and his stomach so large that he looked as if he was sitting on his backside. His appearance in the doorway provoked gales of laughter. He tried to exorcize this demon by directing angelic looks from tiny eyes, lost in a mass of pallid flab, at the mob which he knew full well would be in

uproar in a matter of minutes.The second phase began when Hébert, his back to the class, took on the appearance of a giant insect heaving itself up the blackboard and depositing trails of chalk behind it. Those of us with ammunition bombarded the shabby elytra of his old jacket. Hébert turned round. Not straight away, because he was deaf, although we were never sure if this deafness was due to a deficiency of hearing or of courage. The fact was that he left it till the last possible moment before taking on the miscreants, and when he decided to act, it was plain to see that he did so reluctantly. He turned round suddenly.

The third phase was then initiated, in which he exhibited his truly royal character, itself contradicted by his uncertain gaze and the despairing grin beneath his great moustache, once red, now stained with tobacco. First of all, he drew a small silver case from his jacket pocket, took an enormous pinch of snuff and then commenced his harangue: beautifully phrased, carefully formulated, full of solemnity, but completely inappropriate. This was his great talent. His words conformed neither to his

features, nor to the circumstances of his predicament. He threatened the innocent, avoided the guilty. His pupils were so insulted by the obvious injustice as to become lovers of justice themselves.It was during these feats of oratory enunciated through glittering tears that Jarry came forward. He joined the fray at the end, like a matador entering the arena for the coup de grâce. Complete silence reigned. Coldly, cuttingly, he put insidious and bizarre questions to Père Heb, who faltered in mid-sentence, his self-righteous manner shattered. Jarry encircled him, stunning him with aphorisms. He demolished him, Père Heb became disconcerted, batted his eyelids, stammered, pretended not to hear, lost his footing. Finally he gave way, collapsing on the table amidst the retorts and apparatus, scrambling for his spectacles, and with a trembling hand he would scribble a note to the headmaster. The class regarded Jarry the victor with a sense of wonder.

And also with trepidation and disquiet, because we felt that Jarry’s sarcasm went far beyond the general unruliness, that something within him, some powerful impulse, lay behind the ferocity of his attack. Already it seemed as if Père Ubu was coming into being, modeled on Jarry’s victim.

Jarry hds his quarry, the embodiment of all that is wrong, old, obsequious, fawning, narcissistic, failed, trapped, staid and stale. He recreated Père Herbert as a puppet show, then as a shadow play. Père Herbert swells and mutates. In 1891, Jarry recasts M. Hébert as the ovoid Ubu, a man of inflated girth and insatiable desires who aims to become King of Poland. Along the way he betrays his followers, overtaxes the plebs, kills pretty much everyone, including the incumbent King of Poland, and rows with his unsentimental wife, Mère Ubu, a potty-mouthed shrew. The power-mad leader’s rise ends when he is chased back to France by the invading Russian army.

What Monsieur Hébert made of his role, we don’t know.

On that legendary first and last night, Jarry took to the stage, his face painted white. He addressed the audience, comparing his work favourably to Shakespeare’s oeuvre. “Il serait superflu,” he opined, “outre le quelque ridicule que l’auteur parle de sa propre pièce- que je vienne ici précéder de peu de mots la réalisation d’Ubu Roi…”

Behind him was a backdrop, decorated with what appeared to be random scenes. It never changed. When they appeared, the actors were wearing masks. They spoke and moved mechanically. The play was, said the critic for Le Petit Parisien, a ‘scatological piece of insanity’. Another audience member, W B Yeats was pricked to wonder, “What more is possible? After us, the Savage God.”

Like punk, lots of people think they know what Ubu Roi was but few really do. As Malcolm McLaren put it, “kids today are waiting for something to happen.” Ubu Roi was a something.

Noted but not minted, Jarry lived his art. Evicted from his apartment for non-payment of rent, in an act of absurdity that aped his artistic output, he moved into the ‘second and half floor’ at 7 rue Cassette. The floors had been divided in half along the horizontal. Even the diminutive Jarry, only 1.61 meters tall, was barely able to stand up.

Not that standing tall was his primary concern. Memoirist and femme de lettres Rachilde (the pen name of Marguerite Vallette-Eymery (February 11, 1860 – April 4, 1953)) described a typical day in the life of her friend:

Jarry began the day by consuming two litres of white wine, then three absinthes between ten o’clock and midday, at lunch he washed down his fish, or his steak, with red or white wine alternating with further absinthes. In the afternoon, a few cups of coffee laced with brandy or other spirits whose names I’ve forgotten, then, with dinner—after, of course, more aperitifs—he would still be able to take at least two bottles of any vintage, good or bad. Now I never saw him really drunk….

Through drink – and when not booze, Jarry enjoyed a tot of ether – “he becomes,” noted Rimbaud, “the sickest of the sick, the great criminal, the great accursed,—and the Supreme Knower!—For he arrives at the unknown!”

Arthur I. Miller, in Einstein, Picasso: Space, Time And The Beauty That Causes Havoc, notes that while Jarry might not have been the greatest wordsmith, he possessed the power to stir, inspiring no less a figure then Pablo Picasso to behave in a peculiar manner. Picasso was in habit of carrying a pistol filled with blanks.

He [Picasso] would fire at admirers inquiring about the meaning of his paintings, his theory of aesthetics, or anyone daring to insult Cézanne’s memory. Like Jarry, Picasso used his Browning as a pataphysical weapon, in a sense playing Père Ubu au natural, disposing of bourgeois boors, morons and philistines.

For the uninitiated, “Père Ubu” was a character in an early play of Jarry’s. In the work, Ubu has a conversation with his conscience about how harder sciences like geometry needed to be inserted into conversations of art, mainly because Friedrich Nietzsche had recently declared God dead and artists, Jarry implied, needed to fill the epistemological void.

Pataphysics is Jarry’s ‘self invented but universally recognized science’. It focuses on studying the exceptional and

the coincidental. In 1948, a collective of avant-garde writers and artists formed the College de ‘Pataphysique. Members included Eugene Ionesco, Joan Miró and Marcel Duchamp.

Said Jarry:

Pataphysics will be, above all, the science of the particular, despite the common opinion that the only science is that of the general. Pataphysics will examine the laws governing exceptions, and will explain the universe supplementary to this one; or, less ambitiously, will describe a universe which can be – and perhaps should be – envisaged in the place of the traditional one.

Got it?

After his death, the vicious tale of the voracious Ubu Roi was performed in marionette theatres. As Mr Punch himself is wont to say, “That’s the way to do it.” Make it nasty, chaotic, incomprehensible and above all energetic and let the punters make of it what they will. And if all else fails introduce a crocodile and and have it smack someone about the head with plank of wood.

Jarry was a notorious cycling fanatic. It was said he sometimes rode around Paris with two revolvers tucked in his belt and a carbine across his shoulder occasionally he would fire one of the guns to warn people he was coming. For the same reason he once fixed a large bell from a tramcar onto his bicycle. He criticised those who “thinking themselves poets, slowed down en route to contemplate the view”.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.