Fierce debates over the compelling, or disturbing, portraits taken by Diane Arbus have occupied critics intensely perhaps because the controversial questions that surround her work fall so far outside the provenance of the frame. Inherently juicy issues of privilege, power, and the psyche of the artist provoke and enrage. Arguments and speculations cross perennially contested territory, and Arbus’ suicide in 1971 adds an additional layer of morbid fascination to her legend. “Are her portraits—of circus performers, transvestites, mentally disabled people and others—empathetic acknowledgments of a shared humanity,” asked a much-belated New York Times obituary, “or are they exploitative depictions that seize upon their subjects’ oddities to shock her audience?”

Whatever answers we offer say as much about our own social theories as they do about Arbus, but they say potentially nothing about the images themselves. It is worth noting that Arbus did not profit from her subjects’ pain—or perceived pain. “During her lifetime, there was no market for collecting photographs as works of art,” and while she survived by shooting commissioned portraits and fashion spreads for magazines like Harper’s Bazaar and New York Magazine, her own prints “usually sold for $100 or less.” When we look away from the artist and at her work, we can see that what drew her also draws us in—we stare, hoping to understand something seemingly hidden in plain sight. As she once said, “a photograph is a secret about a secret. The more it tells you the less you know.”

Maybe the violent reactions her work provokes show us how dangerous it feels to simply encounter other people, especially those unlike us, without the hedging of performed niceties and predetermined narratives. Charges that “poor little rich girl” Arbus craved suffering as a way out of ennui have stuck, I suspect, in part because they assuage the discomfort we feel when looking at her work—easier to displace such feelings onto the artist. But “to say that she slummed would be unfair,” notes Anthony Lane, defending her portraits of outcasts. Though “calls of social responsibility… meant little to Arbus,” they also meant little to some of her photographic subjects, those who “had elected to cast themselves out” of society. “

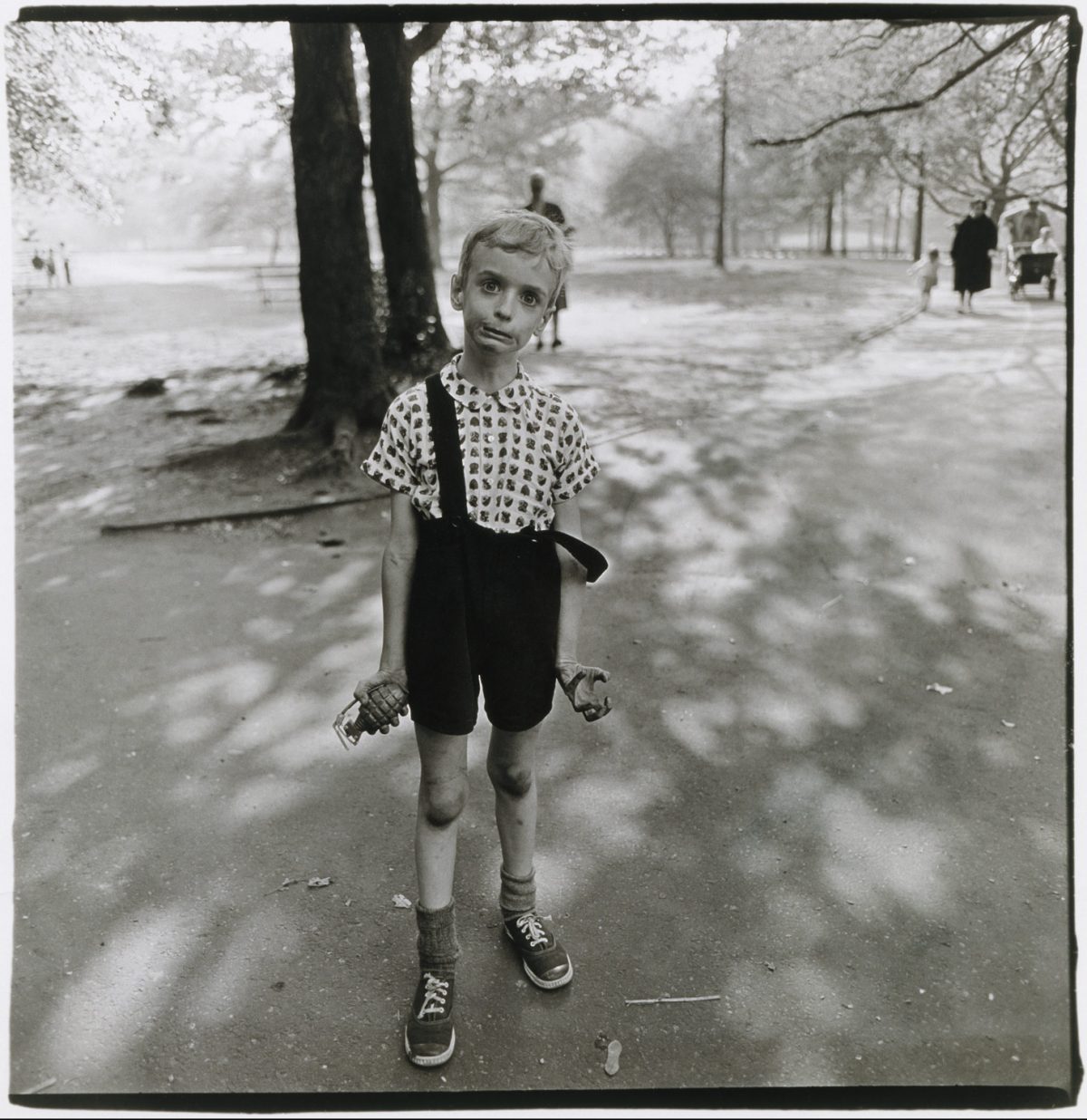

The question of agency should always be central. The “freaks” Arbus photographed always meet her gaze. Despite Norman Mailer’s clever quip that giving her a camera was like giving a child a live grenade, her images did not destroy them. Whether they ennobled, demeaned, or any other social act may be a secret shared eternally between subject and photographer, or a concern neither of them shared.

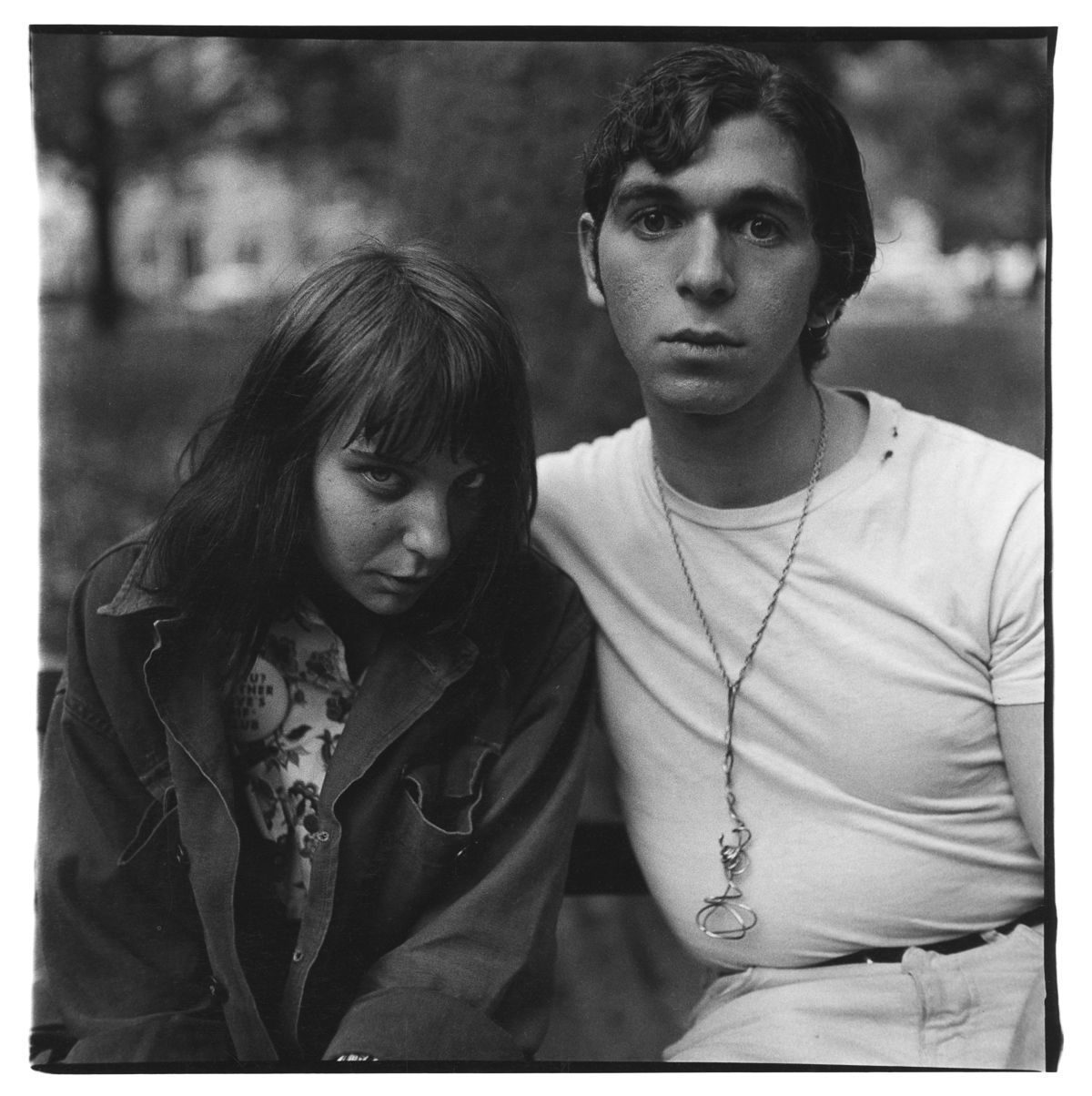

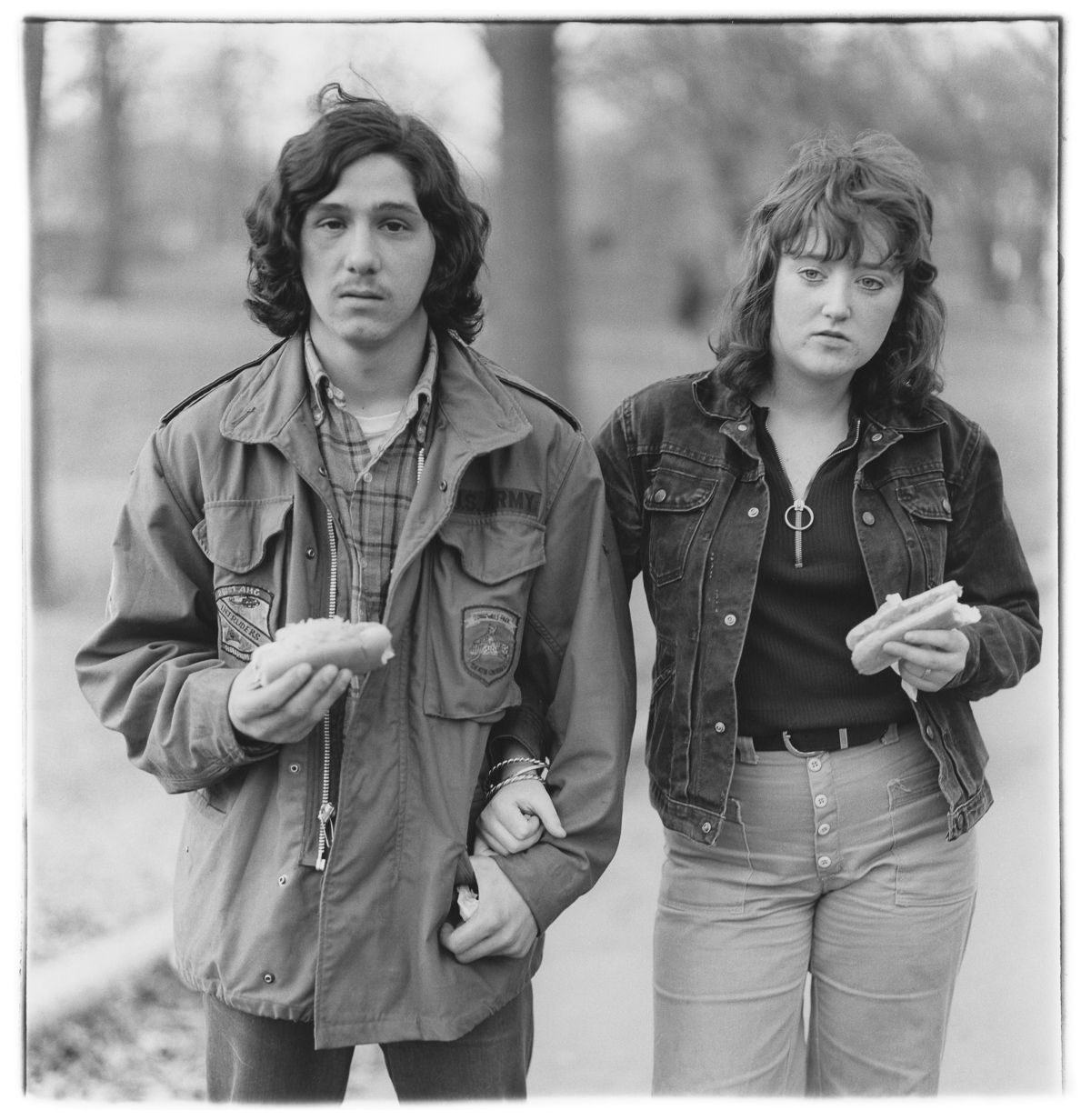

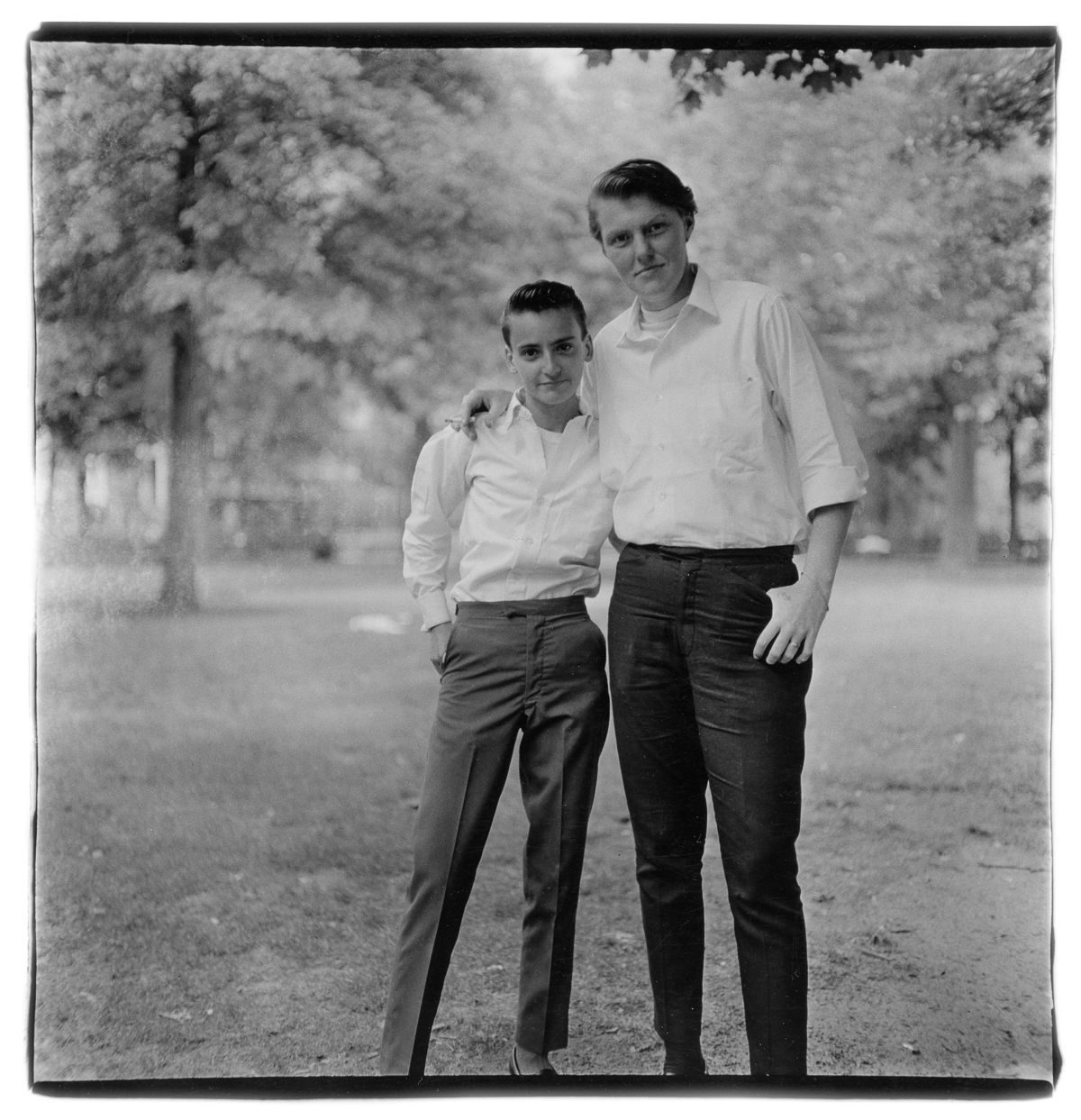

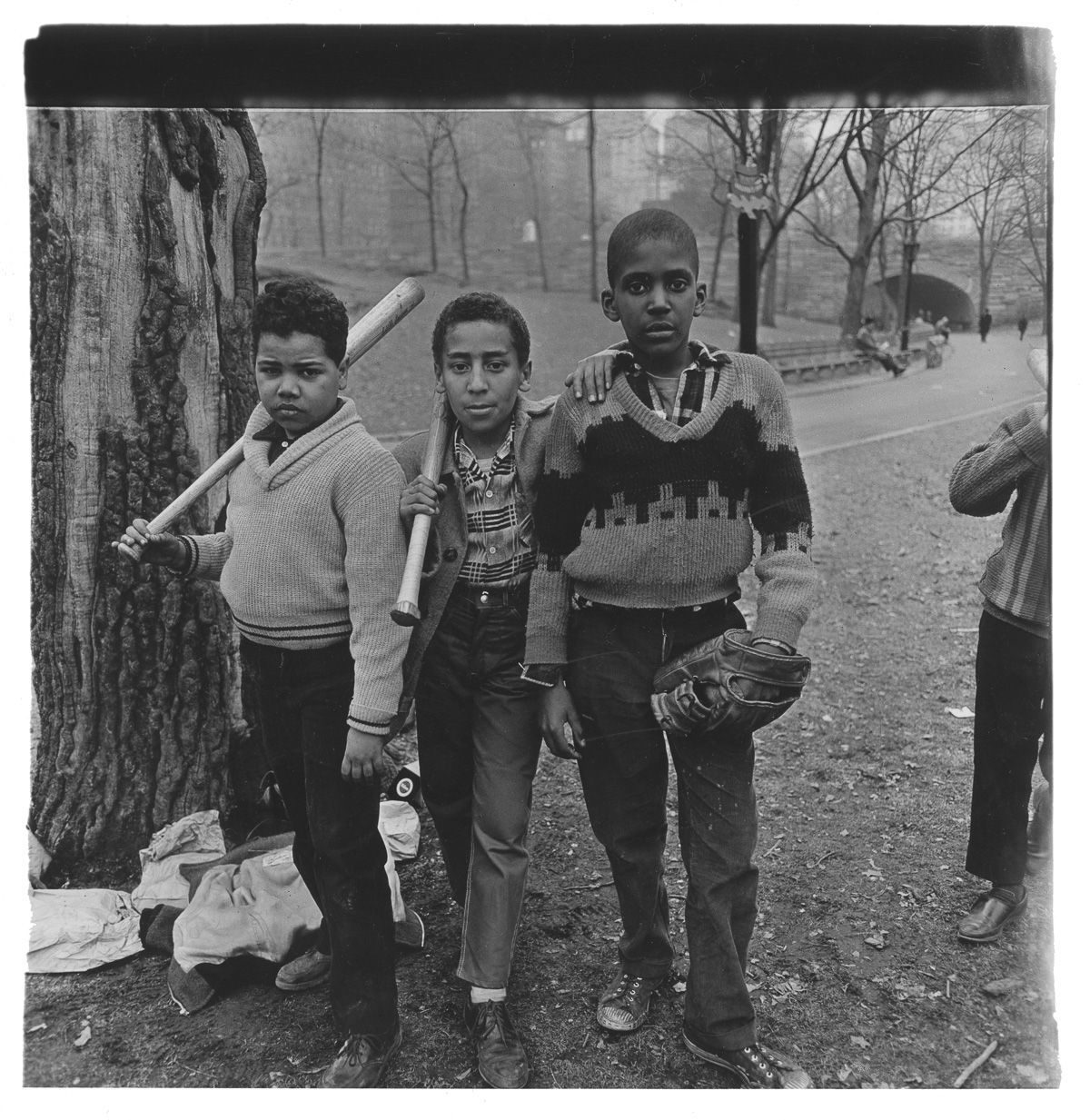

Her own commentary about her subjects sometimes waffles between anthropological detachment and the half amused/half disgusted observations of the inexperienced tourist. But as viewers outside the relationships she formed with her subjects, we can approach each photo anew, creating our own bonds with the haunting looks, piercing gazes, pursed lips, sneers, smiles, etc. that meet us in the faces she documented: faces that are unusual, marginal, odd, but are also totally unremarkable at first, as in her many photographs of New Yorkers in Central Park and Washington Square Park (many, in her words, “hippie junkies, lesbians, winos”).

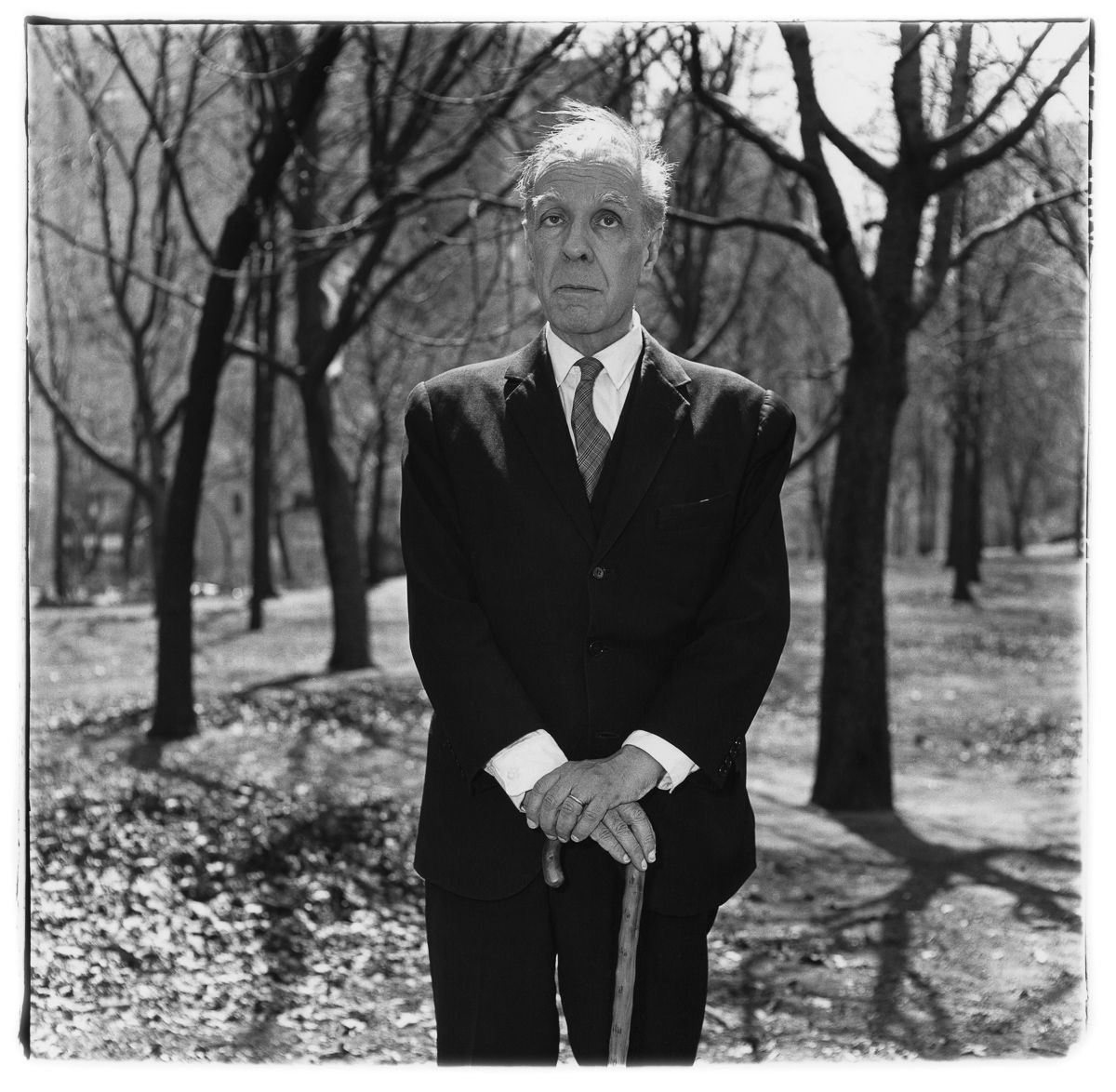

Perhaps the immediate question that comes to mind when viewing Arbus’ work is why one kind of face should be treated, by the human or the camera’s gaze, differently from any other. The photographs here, including a dignified Jorge Luis Borges, further up, in 1969, come from Arbus’ many excursions in the park throughout the 60s and early 70s, during which she took the famous photo, “Child with a toy hand grenade,” in 1962. An original print sold in 2007 for two hundred and twenty-nine thousand dollars. The Museum of Modern Art paid Arbus around $75 for the work in 1964. The child in the photo, Colin Wood, believes, he revealed in 2012, that Arbus saw in him exactly what there was to see, “the frustration, the anger at my surroundings, the kid wanting to explode but can’t because he’s constrained by his background.” Other secrets lurk there too, the mystery of human presence captured on film for an instant.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.